“Stainless Steel Dream,” the leadoff track from Living Hour’s fourth record, Internal Drone Infinity, begins with a manic, glitchy din. The sonic assault ends abruptly, swiftly contained, giving way to a lone bass and singer Sam Sarty's hushed opening lines: “Pink hair straightener, baby, messy messy dresser in a dark room, empty.” Less than 60 seconds goes by before the Winnipeg-based band ascends into a squall of noise and just as quickly calms themselves again. Internal Drone Infinity is defined sonically and lyrically by this tension—the push-and-pull between order and chaos, quiet and loud, inner and outer universes.

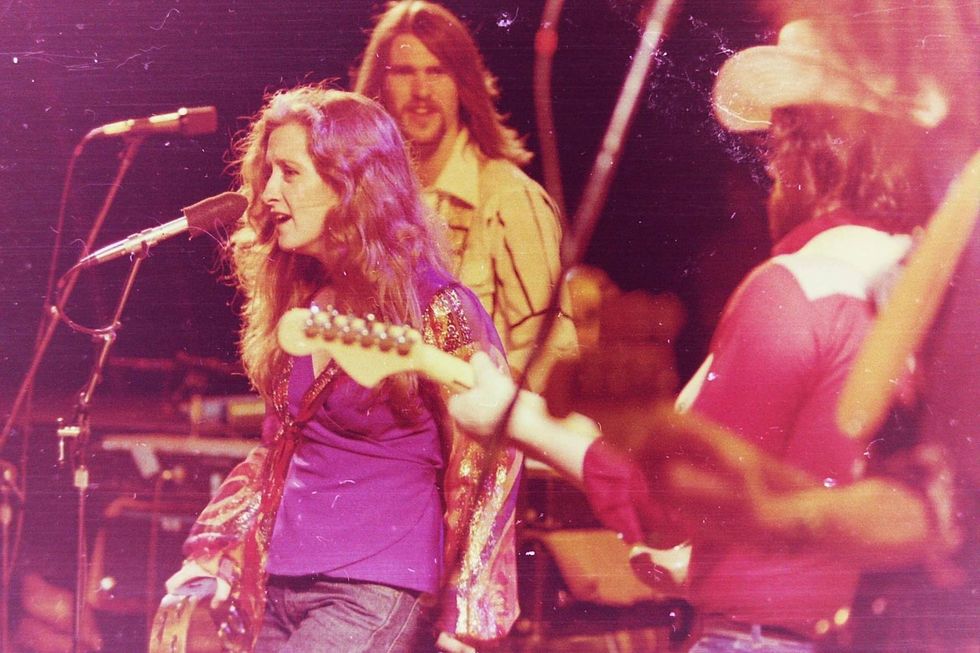

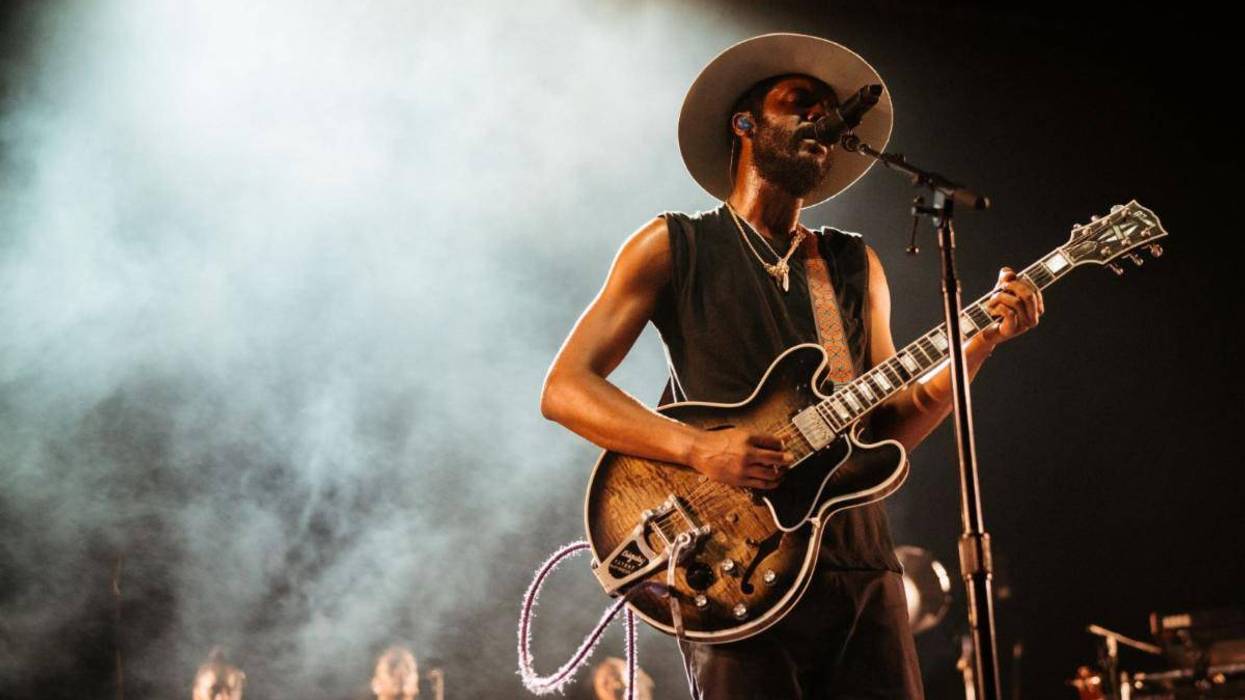

Living Hour, in vocalist and bassist Sam Sarty’s living room, which doubles as their jam space: (l-r) Isaac Tate, Gil Carroll, Brett Ticzon, Sarty, and Adam Soloway.

Matt Horseman

“I was thinking a lot about how anxiety and thoughts exist in your body and in the small decisions you make everyday and in what you see in the world,” Sarty says over the phone from her grandfather's house on Vancouver Island. “Your whole life is based on your perception of what you’re seeing. Then I thought about how anxiety and busy thoughts color that and affect it and change your whole life. When I’m feeling really extreme, I think, ‘Oh yeah, you could just die because a bee would buzz into your face and you’d freak out and fall off a cliff or something.’”

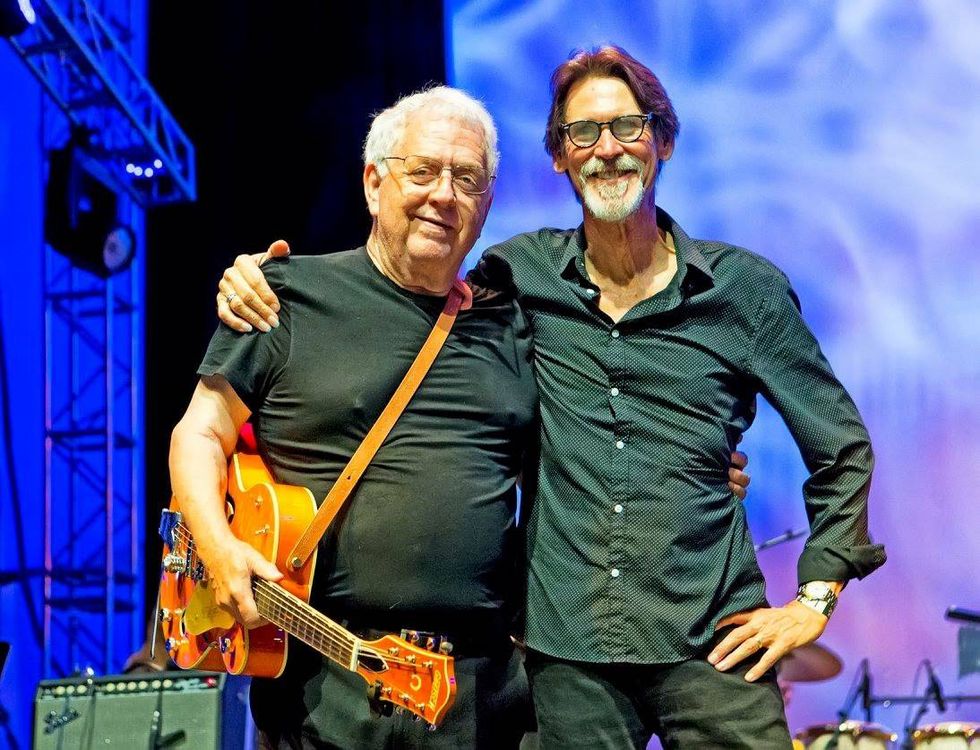

A typical response to existential dread is often grasping for control. On Internal Drone Infinity, this manifests in Living Hour’s gravitation toward precision in the midst of turbulence—in moments like the spiralling outro of “Wheel” or the feedback-heavy ease-in to “Big Shadow,” it’s as if the band has simply figured out how to put their hands around noise and turmoil and shape them to their whim. This move toward punchiness and away from the gentler, gauzier sounds of 2022’s Someday Is Today could be attributed to a number of things—the scientific rigor with which guitarists Gil Carroll and Adam Soloway tend to their tones, Sarty’s writing more guitar parts, or Carroll’s shift from mostly clean sounds to incorporating fuzz, distortion, and overdrive. (“Swiss army knife” multi-instrumentalist Brett Ticzon also handles a few guitar details, while drummer Isaac Tate plays one upside down on “Big Shadow”).

“We were kind of inspired by the band Superheaven, who I’m sure play their guitars through these massive stacks and get huge, huge guitar chord tones,” Soloway says. “But we were still working with our little amps, so we would be recording six different guitars doing different versions of a chord to try to make it sound as huge as possible, stacking them on top of each other.”

On their new LP, Internal Drone Infinity, Living Hour recorded on small amps, but built layers of tracks to achieve a massive sound.

It’s likely, though, that the most significant change is that Sarty is confronting some of that aforementioned dread defiantly instead of turning away or opting for resignation. “Everyone’s kind of angry, we’re getting pissed, the world is fucked, and sometimes it feels like I can’t just be in a nice indie rock band anymore playing twinkly things,” Sarty says. “It’s still nice to do that, but I think there needs to be a release, a scream or a grunt or something.”

Internal Drone Infinity offers a lot of moments for that kind of release, often in the shape of incredibly sharp, layered, fuzzy freakouts—like on “Firetrap,” a Soloway joint that wrestles with the weight of the onslaught of violent images and videos online, or “Half Can,” which adds Jenna Wittman’s unsettling violin to the commotion.

Sarty’s precise sense of composition, tone, and execution likely stems from an obsessive impulse she’s had since childhood—to photograph and write about whatever catches her eye, whether it’s garbage or cheese. Combined with the fact she was writing these songs while working as a projectionist at Winnipeg’s independent movie theatre (“It’s a really cool job, because you can watch so many movies for free and you feel like a weird, twisted Gremlin”), Sarty has long been tuning her attention to small details, a practice which, like auteur cinema, creates its own dreaminess.

Gil Carroll’s Gear

Guitars

Fender American Telecaster

Amps

Fender Vibrolux

Effects

Boss TU-3

Boss VB-2W

JHS 3 Series Distortion

Xotic EP Booster

Strymon Big Sky

Strymon El Capistan

Strings & Picks

Rotosound Roto Reds (.011–.048)

Adam Soloway’s Gear

Guitars

2015 Fender Classic Series ’60s Jazzmaster Lacquer with Mastery bridge

2020 Gibson SG Tribute

Amps

Fender ’68 Custom Deluxe Reverb Reissue

Effects

Boss TU-3

Electro-Harmonix POG

Fairfield Barbershop

Pro Co RAT

EarthQuaker Colby Fuzz

Boss TR-2

MXR Carbon Copy

Strymon Blue Sky

Electro-Harmonix Freeze

ZVex Instant Lo-Fi Junky

Strings & Picks

.88 mm guitar picks

.011-gauge string sets

Sam Sarty’s Gear List

Guitars & Basses

Fender Baritone Telecaster

Squier Jazz Bass

Amp

Ampeg Micro-CL

Effects

Electro-Harmonix Bass Big Muff

Korg Pitchblack XS

Way Huge Echo-Puss

Pro Co RAT

Brett Ticzon’s Gear

Guitar

Gibson SG Tribute

Effects

TC Electronic PolyTune

Electro-Harmonix Op Amp Big Muff

Boss DS-1

Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail

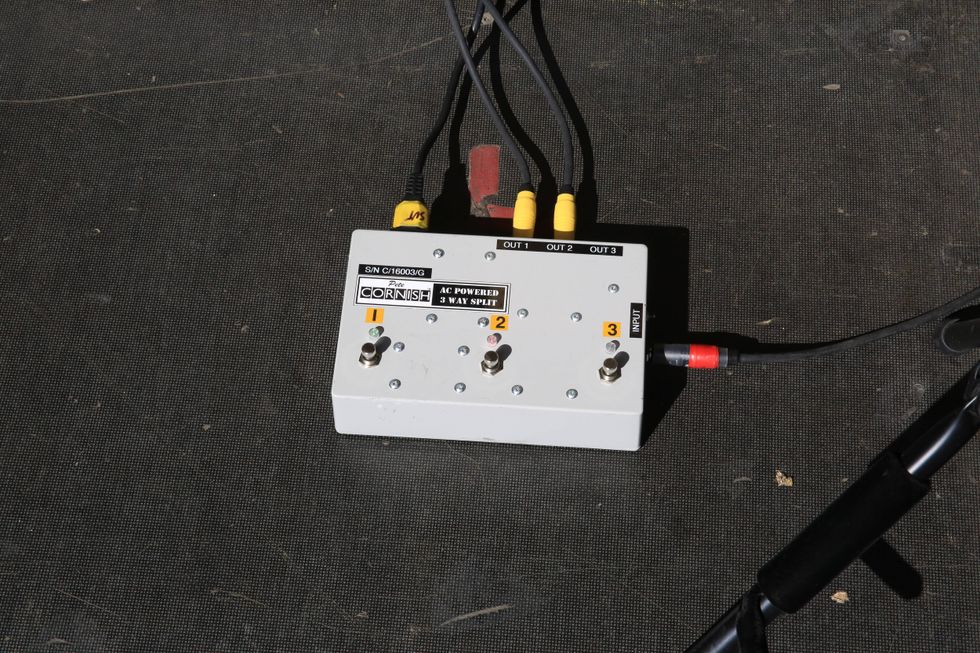

Living Hour give their gear some cuddle time.

Matt Horseman

The low-key “Texting” maybe the most pining song on the record—which is saying something for a band that calls their music “yearn-core”—provides a poignant example of this phenomenon. The accumulation of mundane observations produces a strangeness much like that which emerges when you simply gather the seemingly disparate fragments of reality around you: “Sunwashed plastic garbage bin, blue now from the cornflower sun, handles like madonna’s nails; picking zits in Home Depot, and the tread in your shoes.” Elsewhere, there are isolated non-sequiturs (“soft chorus of cellos,” “rabbits looking”) and painful clarity: “I walk home from the movies ’cause I don’t have a car anymore / At 29, I feel sick, but I’m just getting started on my medicine.” It’s kind of like if the poet Mary Oliver had strolled the garbage-strewn and overgrown, busted-concrete back alleys of Manitoba’s capital instead of her peaceful Cape Cod forests.

“‘Texting’ is very much about Winnipeg,” Sarty says. “I was really thinking about moving during Covid, and then after I was like, ‘Okay, it’s my moment.’ But then I can never really leave. It just gets sticky.”

Stickiness—in this case, the stickiness of long-running relationships—is the tacit catalyst in this mixture that’s allowed Sarty to “come into her own as a songwriter” or for the band to record their “funnest album yet,” as Carroll notes. Closeness and intimacy—Carroll lives on the top floor in the same duplex as Sarty, whose apartment is also the band’s jamspace—plus time creates intangible and fluid dynamism. And at this point in their long collaboration, the band members are comfortable with taking the chaos of their 21st-century lives and, with each other’s help, making some order out of it.

“I can imagine a lot of bands struggle with delivering feedback about parts or when they want things to change in a song,” Carroll says. “And obviously we still have those conversations with care, and we’re gentle, but like, Solly can tell me, ‘That tone’s not working.’ Or we can say, ‘Sam, you need to tune your guitar.’ It’s good—that makes the song and the band better, and people are able to receive feedback, which I think has made our songs better, too. It’s like The Rehearsal season two. I’m Captain All-Ears when it comes to my tone.”

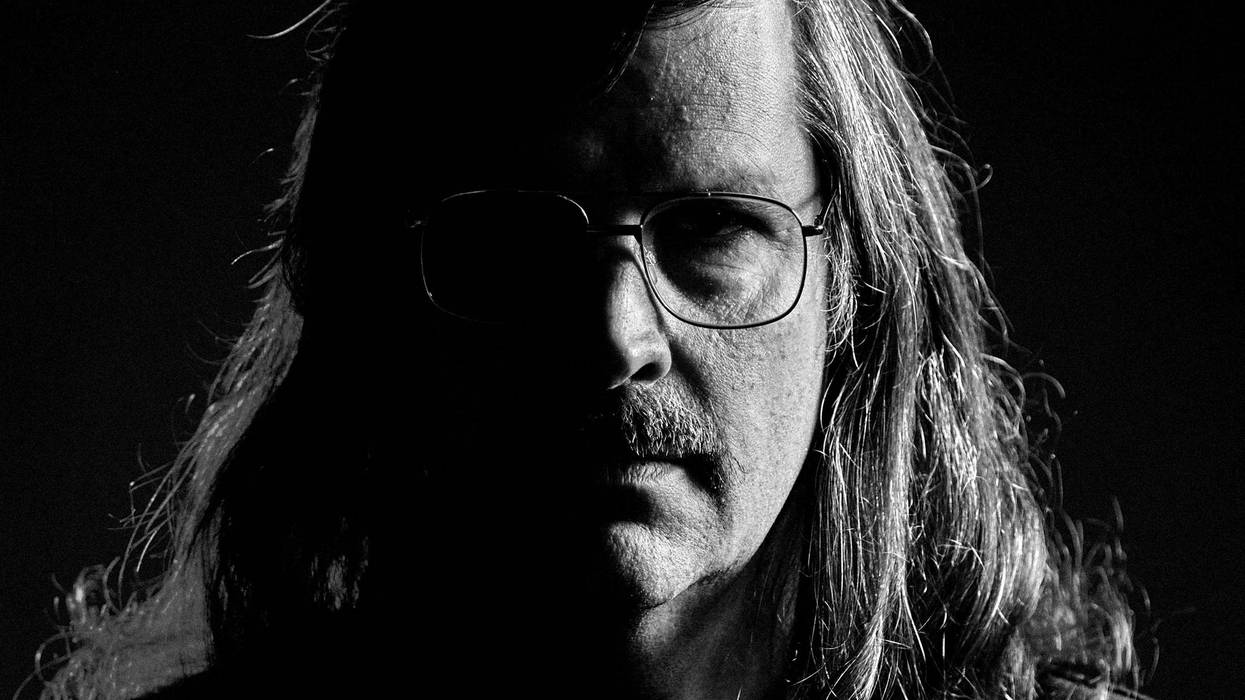

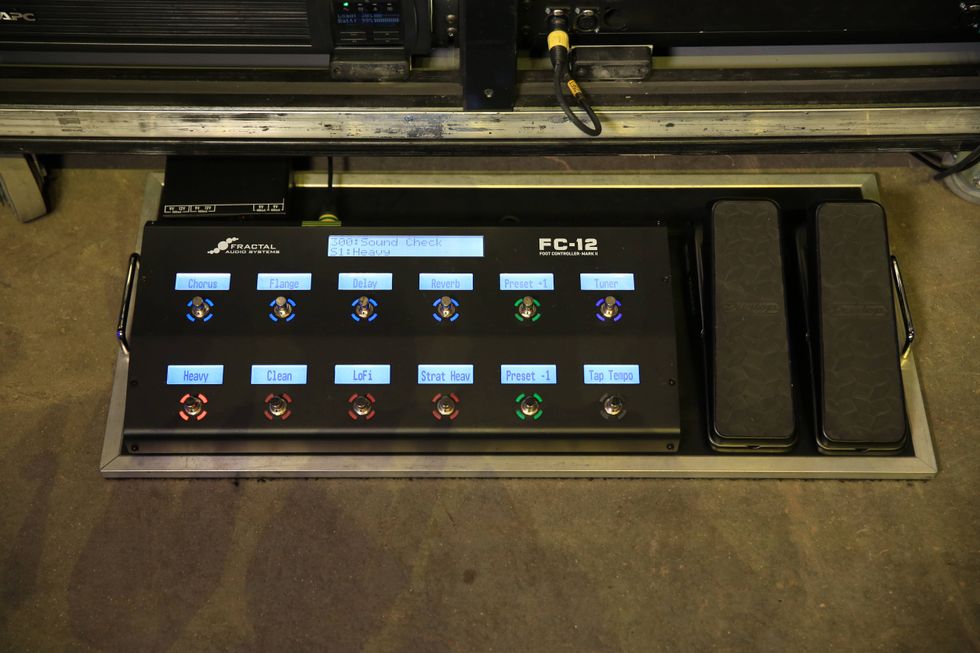

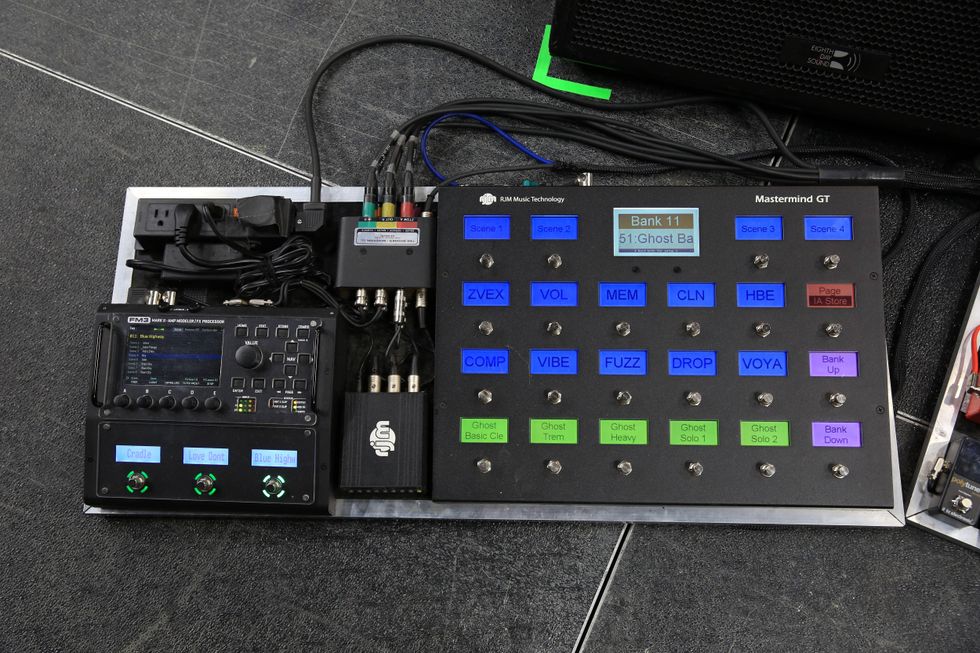

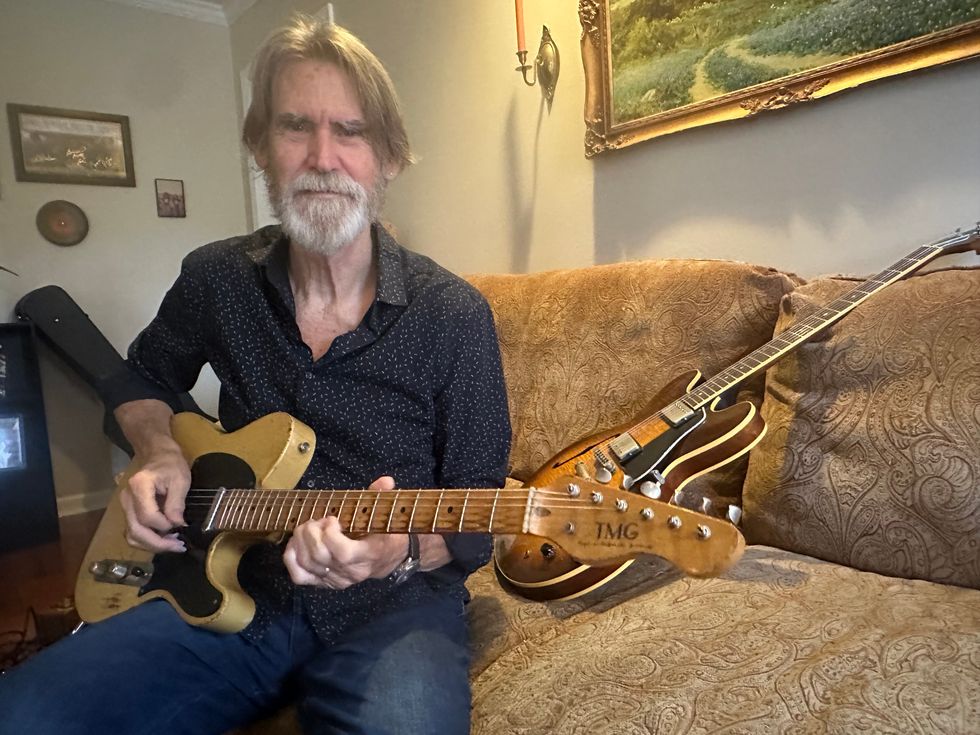

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski