Carlos O’Connell deforms his guitar with an unusual ordering of shapeshifting stompboxes, while Conor Curley embraces jangling and kerranging melodies on his hollowbody howlers. Together, they combine for a charming, chaotic chemistry.

Irish rock band Fontaines D.C. is a dual-guitar ensemble featuring Carlos O’Connell and Conor Curley. At first, the duo used similar guitars, amps, and settings in an effort to work as a symbiotic saw buzzing their way through songs. The indistinguishable incisions lacerated their earliest work with angsty piss and vinegar. But as the quintet’s musicianship has evolved, they’ve embraced wider influences, adding different knives to their collection of cutlery. And more specifically, they’ve learned when to slice, when to dice, and how to work off each other.

“I think we’re trying to be more patient and more conscious of the texture,” Curley told PG in 2022, describing how he and O’Connell have worked together to refine their sound. “The first album was very much in a fighting mode,” he continues, “with the two guitars EQ’d the same and just smashing off each other. On the second one, we learned to play together a little better. We’re still working on it, and sometimes we still try to become as one almost, when the song needs it, but I think now we’ve learned to fit in with how we’re EQing everything. It feels really good.”

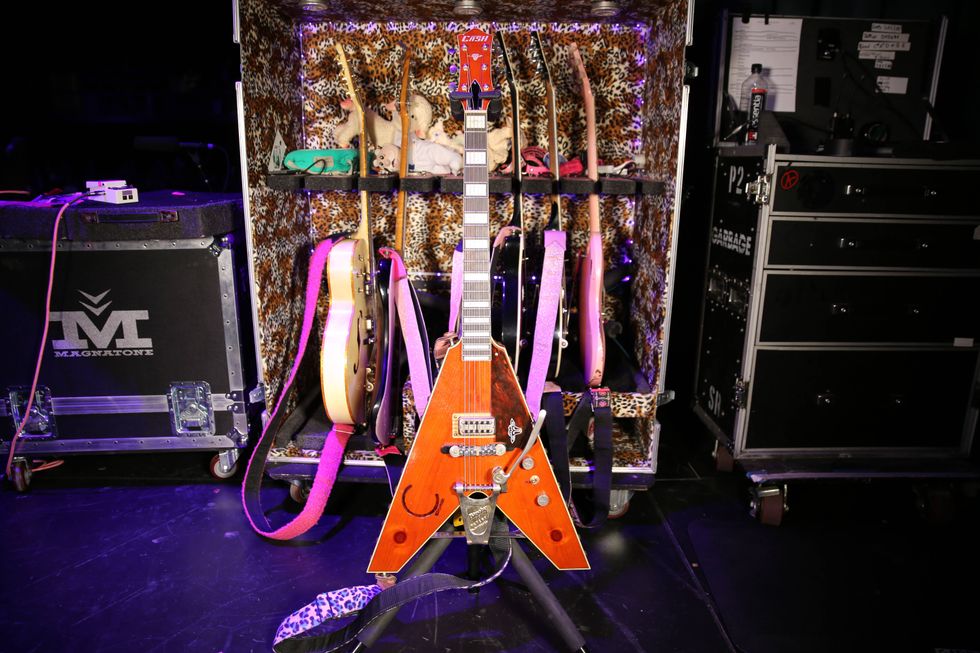

Ahead of their opening slot priming crowds for the Arctic Monkeys, O’Connell and Curley invited PG’s Chris Kies onstage at the Ascend Amphitheater in downtown Nashville. Carlos covered his favored Fender solidbodies, while Conor showed off his eclectic hollowbodies, and they both walked through their respective pedalboards.Brought to you by D'Addario Trigger Capo.

A Punchy Pinger

While recording with producer Dan Carey for 2022’s Skinty Fia, Carlos O’Connell fell for Carey’s mid-’60s red Fender Mustang. To replicate the album’s tones onstage, he found a similar ’Stang online. The listing originated in N.Y.C., so he had a friend at the band’s label, Partisan Records, scoop up the instrument. O’Connell was finally introduced to it before a U.S. tour, but there was something immediately wrong. The student model instrument normally came in a compact 24" scale, but a handful of ’65 & ’66 Mustangs, including this one, left Fullerton with an even shorter scale length of 22.5". O’Connell admits any guitar work handled beyond the 12th fret gets cramped, but he loves the small steed’s “snappy, pingy, high-end punch.” For a song like “Televised Mind,” he’ll engage the out-of-phase switch in conjunction with a Moose Electronics Cosmic Tremorlo. The combination intensifies the shrillness of the guitar for an undeniable sting. All of O’Connell’s electrics take Ernie Ball Burly Slinkys (.011–.052).

Irish Icon

O’Connell scooped this Fender Custom Shop Rory Gallagher Signature Stratocaster with a heavy relic from Chicago Music Exchange. He wanted something to contrast the ping of the Mustang with a guitar that had a heftier, chunkier sound, which would add more low end for the band’s D-standard songs. The Strat was the perfect foil, and the replica based on Rory’s 1961 is a fitting way to honor his fellow Irishman.

Secondary Strat

Backing up the Rory Strat is Carlos’ Fender American Vintage II 1961 Stratocaster.

Hi-Hat Chime

“I can’t stop thinking about the guitar as an extension of the drum kit,” explains O’Connell. “I don’t think it should exist on its own in a song. It needs to back something up—you’re either following the vocals or you’re following the drums. You can do without guitar in songs, but you can’t do without vocals or drums.” For “Roman Holiday,” he runs this Martin J12-15 Jumbo 12-String into a Fender ’68 Custom Deluxe Reverb, with a bit of extra spring splash from a reverb by Moose Electronics—which he unconventionally places first in the effects chain, ahead of his overdrives—and gain from the MXR Micro Amp that mimics the sparkly crash of hi-hats for rhythm accompaniment.

Double Trouble

O’Connell’s core tone comes through the Fender ’68 Custom Twin Reverb. It’s always on, and he’s always plugged into the vintage channel with the bright switch engaged for primo piercing. He kicks on the ’68 Custom Deluxe Reverb for added oomph during louder bits.

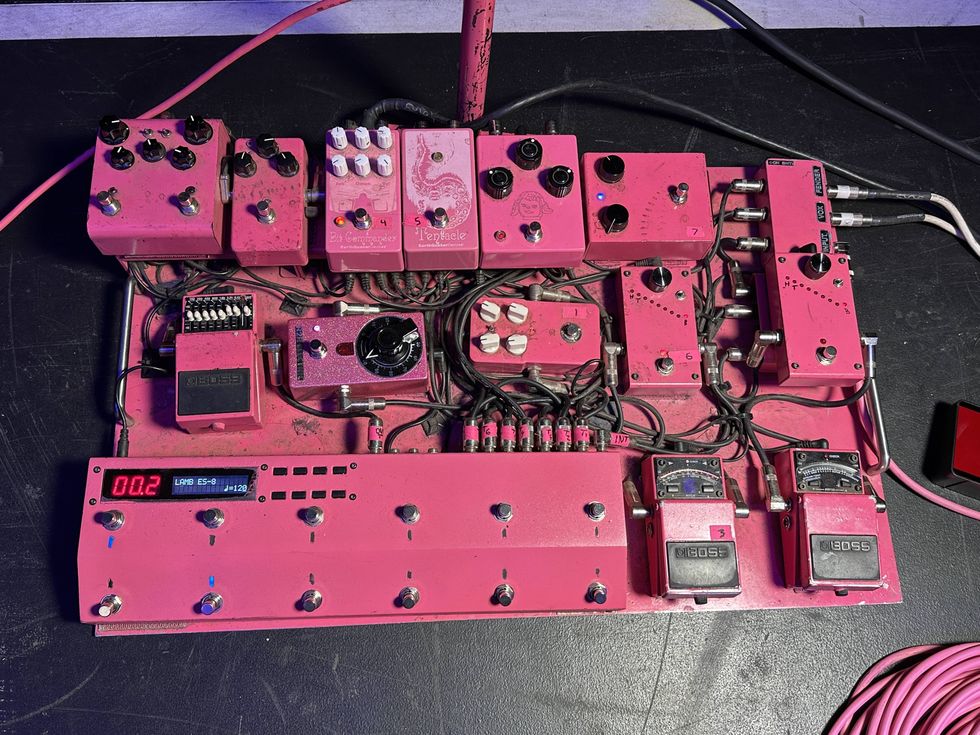

Carlos O'Connell's Pedalboard

Carlos’ first pedal was the Moose Electronics reverb (The Heart Doctor). When he eventually got a distortion, he put it after the reverb. He didn’t think about it. Any other drives he got thereafter went behind the reverb. “I had no idea it was ‘wrong’ until I took my pedalboard into the studio, and they told me I had to rearrange them because the reverb was too dirty, but I like how it sounds like a snare in a huge room,” admits O’Connell. And the rest of his pedal pals follow the same mantra—anything wrong is right, and anything grotesque is gorgeous.

Dirty devils include a Ceriatone Centura, a Fairfield Circuitry The Barbershop Millennium Overdrive, and an MXR Micro Amp. Tone-twisting modulators include a Moog Minifooger MF Flange, a Boss TR-2 Tremolo, a Strymon Lex, a Moose Electronics Cosmo Tremorlo, and an Electro-Harmonix POG. A Boss GE-7 Equalizer helps shape his sound. Utility boxes in his setup are the Radial BigShot ABY True Bypass Switcher (toggling in and out the ’68 Custom Deluxe Reverb), a TC Electronic PolyTune 2 Mini, a Dunlop Volume (X) DVP4, and an Electro-Harmonix Hum Debugger. A TheGigRig QuarterMaster QMX handles all the switching.

Holiday Hollowbody

While taking a break from Fontaines D.C., guitarist Conor Curley enjoyed some downtime in Berlin. Luckily, he encountered this 1960s Framus 03000 Studio that he took home for roughly $250. The archtop already had the Schaller pickup installed at the end of the fretboard, and he was amazed how well it meshed with distortion: “It just sounded so chubby and big.” He strings the Studio—which gets used on “How Cold Love Is”—with flatwounds.

Key Weapon

Curley’s two favorite guitarists are Johnny Marr and the Birthday Party’s Rowland S. Howard. Both played Jaguars, so Curley’s gravitation to the offset was obvious. Since becoming friendly with this Fender Johnny Marr Jag, he’s appreciated the versatility of its series and parallel switching. To honor Howard, he swapped out the standard white pickguard for a tortoiseshell one that matches Rowland’s beloved 1966 Jag. Besides the Framus, all of Curley’s electrics take Ernie Ball Burly Slinkys (.011–.052).

Some Neck, Somewhere

Ahead of recording their sophomore album, A Hero’s Death, Curley decided to splurge his cut of the record’s advance on a vintage guitar. At Dublin’s Some Neck Guitars, he purchased his first Fender Coronado—his attempt to channel the haunting hollowbody tones of the Brian Jonestown Massacre and the Black Angels. Since then, he’s acquired a few more Coronados, and his main touring one is this late-’60s Fender Coronado II Wildwood model he found in Stoke-on-Trent. His goal, one day, is to have a room full of Coronados. Godspeed, Curley!

Clint Eastman

At one point, Curley was diving deep into Elliott Smith’s electric playing. Smith typically played a Gibson ES-330, but Curley didn’t want to dip into his Coronado money to get an ES, so he opted for this similar Eastman T64/v that shares a lot of the 330’s ingredients, including a 16" thinline hollowbody construction with laminated maple, 24.75" scale length, and dog-ear P-90s (Lollar).

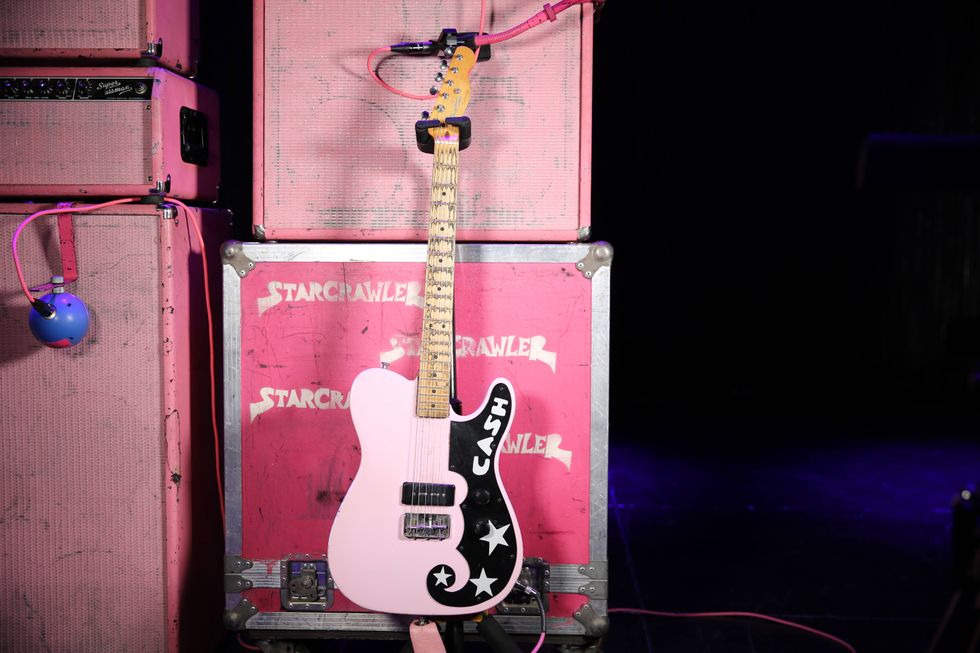

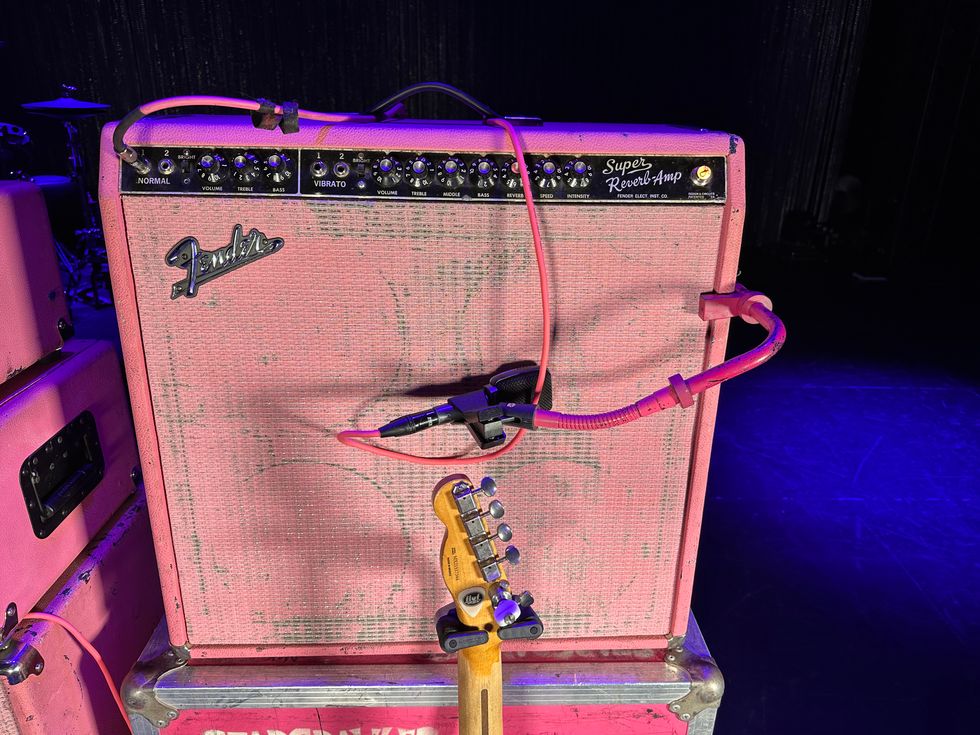

Twin for the Win

Curley plugs all his instruments into this Fender ’68 Custom Twin Reverb because “they don’t flavor anything. They let your guitars sound like your guitars, and they let the pedals do what they need to do.”

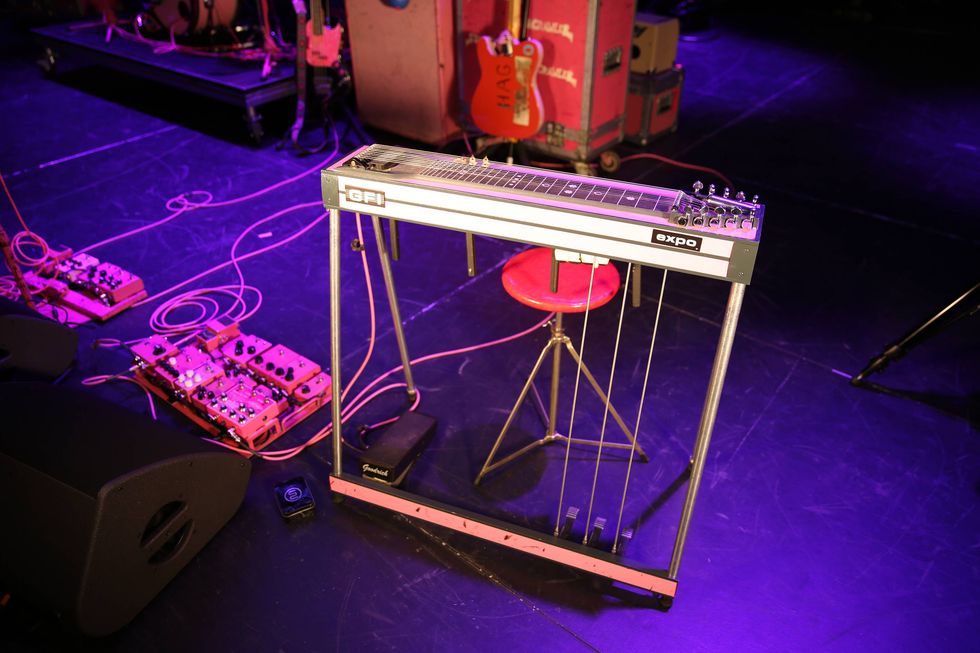

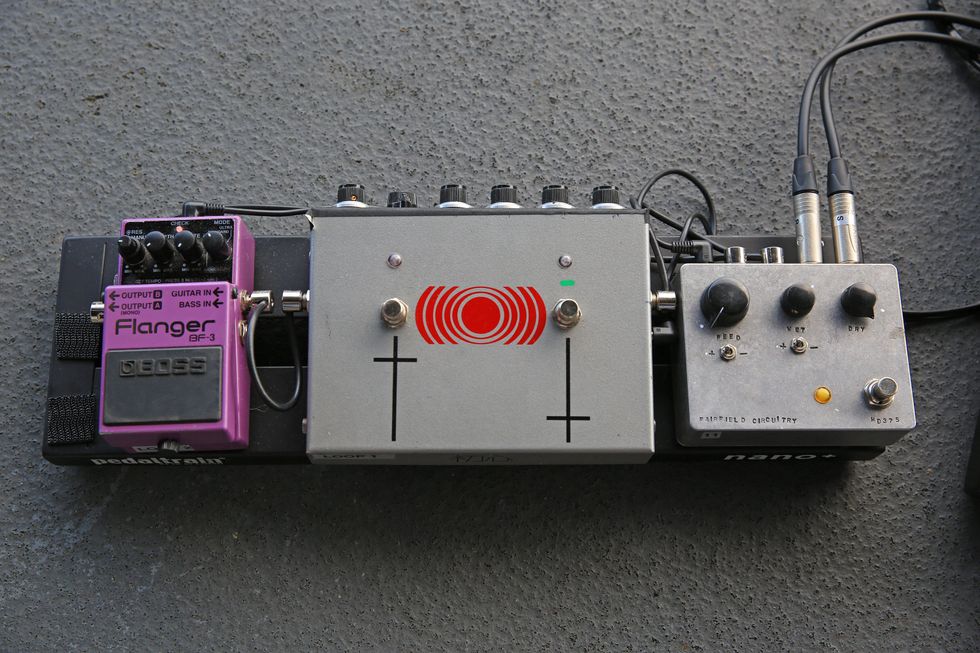

Experimentation Station

Curley has a robust appetite for pedals. This small platter is his rotating appetizer board that is currently testing out a Boss BF-3 Flanger, an EarthQuaker Devices Sunn O))) Life Pedal, and a Fairfield Circuitry Hors d’Oeuvre? active feedback loop.

Conor Curley's Pedalboard

“There were definitely a lot more shoegazey elements that we were trying to get to, and, obviously, if you start talking about Kevin Shields or even Robin Guthrie from Cocteau Twins, the stuff they did, to me, is almost unreachable, but if you try, you might end up with something new anyway,” Curley confessed to PG last year. And to achieve the range of the more ethereal and atmospheric sounds heard on Skinty Fia as well as the more brutish garage bangers in their earlier work requires a buffet of boxes. Curley employs three delays: Death By Audio Echo Dream 2, Ibanez AD9 Analog Delay, and the Industrialectric Echo Degrader. The latter “is so unpredictable, it’s almost like it doesn’t sound the same every time you use it.” He has a pair of reverbs (DigiTech HardWire RV-7 Stereo Reverb and a Boss RV-6 Reverb) and a couple Strymons (Sunset Dual Overdrive and Deco Tape Saturation & Doubletracker). The remaining three devices are a ThorpyFX Chain Home Tremolo, an Electro-Harmonix Micro POG, and a MXR Six Band EQ. A Dunlop Volume (X) DVP4 handles dynamics, and a TC Electronic PolyTune 3 Noir Mini keeps his guitars in check.

Shop Fontaines D.C.'s Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's RigFender Mustang

Fender Rory Gallagher Stratocaster

Fender American Professional Stratocaster

Fender American Vintage II 1961 Stratocaster

Fender Johnny Marr Jaguar

Ernie Ball Burly Slinkys

Fender '68 Custom Twin Reverb

Fender '68 Custom Deluxe Reverb

EarthQuaker Devices Sunn O))) Life Pedal

Boss BF-3 Flanger

Boss RV-6 Reverb

EHX Micro POG

TC Electronic PolyTune3

MXR Six Band EQ

Strymon Deco

Strymon Sunset

Dunlop Volume (X) DVP4

EHX POG

Strymon Lex

Radial Bigshot ABY

Boss TR-2 Tremolo

Boss GE-7 Equalizer

MXR Micro Amp

EHX Hum Debugger

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)