The two first connected by accident when Townsend sent a demo of his project Noisescapes to Relativity Records, Vai's label at the time. Vai was looking for a vocalist, and though Relativity signed Noisescapes, they also suggested Townsend connect with Vai. He did, and ended up singing on Sex and Religion, nailing everything to perfection even though he'd only heard the music the day before the recording session. But this wasn't exactly the happy rock star dream come true. While scoring a gig with the biggest guitar hero in the world should've been a high point, Townsend's tenure was marred by the conflict between his own strong musical vision and his passion for Noisescapes, and Vai's unwavering pursuit of perfection. After the experience, Townsend swore off working under anybody's direction.

Decades later, these two creative giants again crossed paths. In 2005, Vai lent a hand to Townsend's Synchestra album, and in 2013, was cast as narrator on Townsend's live album, The Retinal Circus. When Vai decided to record this year's Modern Primitive, which features music he wrote in the period between his debut solo album Flex-Able and his groundbreaking Passion and Warfare, he enlisted Townsend to sing on a song entitled “The Lost Chord." For both musicians, there was a lot of historical weight attached to this recording, and, in a way, it symbolized both closure and new beginnings.

Modern Primitive was recently released as a double-CD package along with Passion and Warfare 25th Anniversary Edition. Townsend just released Transcendence, and his autobiography, Only Half There, is on the way. Vai and Townsend recently convened to chat about their new projects and clear the air about their touchy past. Part guitar geekery, part therapy, Premier Guitar was there for the ride.

Steve Vai: It's nice to be able to do this. It gave me another opportunity to listen to the record.

Devin Townsend: For me as well, with your record. What number album is this for you, man?

Vai: I lose count. Everybody has different counting systems—how many studio albums, how many albums.

Townsend: You just let it rip on Modern Primitive. Is that all old stuff or is it new stuff as well?

Vai: Aw, thanks. Actually, it's funny because after I finished my first record, Flex-Able, I put a group together and was writing all this weird music, and recording as much as I could. I got as far as tracking about 12 songs and writing a bunch more. It was an obtuse little band, but had really great musicians. Then I joined Alcatrazz and got offered a real record deal. That's when I kind of put all that stuff on the shelf and started working on Passion and Warfare. I always felt like, “One day I'm going to finish that record."

So I went back and picked out about six or seven tracks that were tracked—drums, bass, some rhythm guitar—and then I took a bunch of songs that I'd written back then but never tracked, and recorded them. Then I finished those older tracks. If a person listens to Flex-Able and Passion and Warfare, it's like two totally different guys. That's why I called it Modern Primitive. It's really like a peek into the missing link between those two records. It's like Cro-Magnon Vai, as I like to say.

Townsend: As you were talking, I was thinking that it was a happy accident that the music industry went to shit.

Vai: Laughs.

Townsend: Because now there's no reason to chase radio, and at that point you're just like, “Well what am I going to do?" It seems like this great weight to be liberated from. That need to please that sort of imaginary marketplace. If you're just like, “It's going to sell what it's going to sell anyway, so I might as well go to town."

Vai: The thing I noticed is how free and innocent I was when I recorded all that music. I had no expectations, which is really a great way to make a record. Then you're not trying to please anybody other than yourself. That's all I did back then—like, “What can I do to entertain myself?" In some respects, I drifted away from that here and there over the years, but I've gotten back to it. Because that's really the value in creating anything—pleasing yourself first.

Townsend: I don't know what it's like for you, Steve, but there's a lot of prostitution going on, on my front. I take it where I can get it at this point, because I want to make a symphony. Ultimately if I had to define the process and the theory behind it, I'm an absolute obsessive perfectionist that has never gotten anything right and will never get anything right, fundamentally. So it's this undercurrent of irritation that propels it.

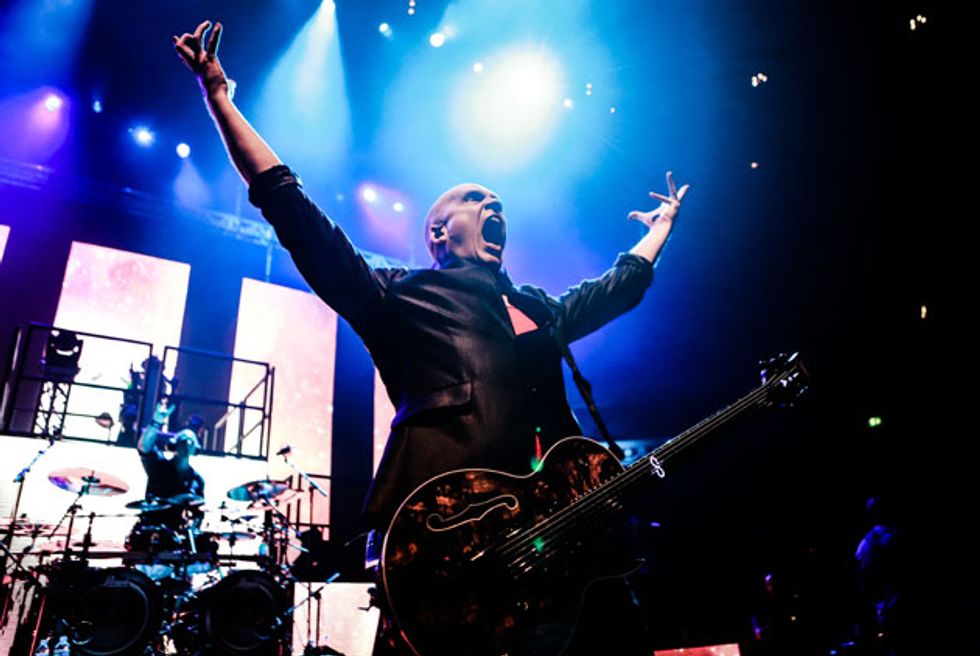

Steve Vai calls Devin Townsend “visionary," but if there is anyone who has done it all with a guitar, it's Vai. Here's Vai eating strings on the Generation Axe tour in May 2016. Photo by Ken Settle

Vai: You're a visceral composer! Dealing with symphonies can be a big boy game when it comes to outlay. There are various ways to get that sound. One is obviously the synthetic way, with samples and whatnot, and sometimes that can be really cool. But if you write orchestral music and have a lot of articulation and dynamics and flow to it, then you gotta get an orchestra. But these days, even that's getting a little easier in that there are more and more orchestras that are hungry to work with young composers coming from a completely different part of the playground. And I've had the great opportunity to work with a whole bunch of orchestras. Even on my last tour I played with six different orchestras, and I actually got paid [laughs]. And they were playing my music. I was able to record it and use it. If you're writing a studio record and you need an orchestra, there's almost no way around having to pay exorbitant amounts with the kind of complexity involved with creating the scores and the parts, and dishing them out. So I've never really done that. I've only created events with an orchestra where I can have them play music, and then I can record it.

PG contributor Joe Charupakorn: Devin, while Steve went to Berklee College of Music, you pretty much became a musician from your late teens on. How did you learn to write orchestral music?

Townsend: I have no idea. If I was to articulate any part of my musical process that's connected to theory, I think I'd be emotionally retarded since as far back as I can remember. It's also interesting that above and beyond the technical acumen or the options that come into it, it's the friction that creates it. It's trying to become an actualized version of whatever the heck you are in this lifetime that just provides constant friction, and I often wonder if the end goal of being a musician is to not have anything to write about any more. Because at that point you're clear completely [laughs].

Townsend and Vai are both known for their expressive, larger-than-life performance styles. Here Townsend summons the crowd during his Ziltoid Live show at London's Royal Albert Hall in 2015. Photo by Christie Goodwin

Charupakorn: You both have very strong musical personalities. What was the dynamic like recording “The Lost Chord?"

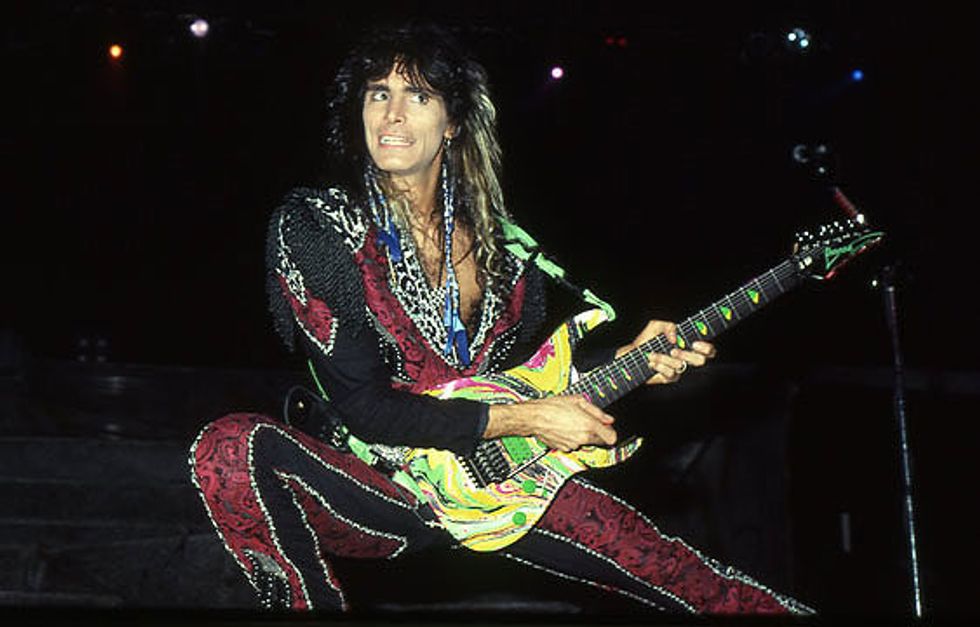

Vai: We both have very strong musical visions and aspirations for the kind of things we like to do. Back when I was starting to work on Sex and Religion, I was pretty focused on that vision—being the composer, the writer, and all that. I needed a great singer and when I heard Devin, I immediately thought, “This guy is great." He was very young at the time and still formulating his own independence as a musician. I mean, you were, like, a teenager.

Townsend: Man, it's that long ago? [Laughs.] You're officially old, by the way.

Vai: I know. I know. [Laughs.] During that process, I worked with a lot of different people but I always felt like when I do my solo work, I have a very rigid approach—“this is my vision and something I want to focus on"—and everybody's contributions came at various levels. I need to be the Svengali, so to speak. Oddly enough there wasn't a lot of creative collaborating, with regards to songwriting or production.

The few songs we did do where I said, “Okay, here's a track. Let's see how it goes," were a Japanese bonus track called “Just Cartilage" and a song Devin and I wrote together called “Pig." They were actually my favorite songs and it was interesting that they helped loosen up the rigid grip I had on the controls. But unfortunately everyone was subject to my neurotic demands. I didn't realize at the time how talented and creative Devin was because he had to unfortunately work under a lot of my direction.

Townsend: If I can play devil's advocate for just a second, my god, dude, I was 19 years old and out of my league in so many conceivable ways that I think a concise musical vision was something that was far from my scope at that point. There's something I wanted to say that I haven't had the opportunity to say, and that's when I was 16, I listened to the shit out of your records. I remember listening to you on [the now defunct radio show] Rockline and the whole works, man. I remember watching Crossroads in my parents' bedroom and loved it. When I finally got together with you, it was such a public thing for me out of nowhere, and I think I was so desperate to have an identity that was separate from that, that my first reaction was to rebel against it all. To be like, “Fuck it. I don't want anything to do with it because I want to be me." The one thing I had going for me was total belligerence. I probably still have it and it's a lot less entertaining in my mid 40s than it maybe was in my early 20s. But in terms of the Svengali-type control of everything, god, if there's anybody that can relate to that, it's me. So I think what you did at the time was what was necessary for that vision. I would have done the exact same thing.

Vai: I innately felt that what we did go through was appropriate.

Steve Vai's Gear

GuitarsIbanez Steve Vai Signature Model JEMs

Amps

Carvin VL300 Legacy 3

Carvin Legacy VL100

Carvin TS100 Tube Power Amp

Carvin 1x12 wedges (two)

Effects

Fractal Audio Axe-Fx XL+

Fractal Audio MFC-101 Mark III MIDI foot controller

Dunlop 95Q Cry Baby wah

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Super Slinkys (.009–.042)

Ibanez heavy picks

DiMarzio straps with strap locks

DiMarzio, Lava TightRope, and George L's cables

Townsend: I totally agree. You become molded by your experiences in whichever way, and a lot of it for me has nothing directly to do with Steve, but just to do with my own reactions to things. Past the Sex and Religion experience, I didn't want to be told how to do anything. That's how that belligerence really played into my musical growth, which eventually became Strapping Young Lad, and a lot of things that were rooted in that kind of mentality.

Vai: I thought, “What the fuck could happen that could bring us back together?" So when I recorded “The Lost Chord," I tried singing it, but I was just ruining the music, and a lot of times when I'm recording something with vocals, in the back of my mind I hear Devin. It's just part of the joining at the hip thing. It did take me a lot to ask him if he would do the vocal, because he's a visionary.

Townsend: You'd done a solo on Synchestra and a bunch of stuff for me with this Retinal Circus thing. A lot of music in this day and age is on the barter system as well. So when you were like, “Would you help me with this verse?" I was like, “Fuck. Yeah, dude, what do you need?"

Vai: Asking somebody to sing the lyrics you write is almost like an intrusion, and it wasn't the optimum collaboration that I think could yield the greatest stuff, like where maybe we're actually starting from scratch. But I sent him the stuff and I guess it worked for him well enough to where he felt comfortable singing the verse.

Townsend: When it came time for “The Lost Chord," I was apprehensive at first only because 20-some odd years in, it carries a lot more weight than simply doing a vocal performance for somebody. It's like the whole experience with Steve was something that started my foray into all of this, so I didn't want to take it lightly.

Vai: In the back of my mind, I thought, “If Devin got a hold of this and went to the wall with it, it would be astounding." And I just said, flippantly, “And if there's anything else you want to do on it …" I didn't expect it, but when I got the music back I had this moment of clarity. It was a great realization for me, and what I realized is that my ideas are not always the best. Whenever you write something, there are always these little delicacies that are important to you as a writer.

Photo by Frank White

That might only mean something to you, and it might just be the way one note flips or the way a chord hits the melody. It's so rare that you feel that somebody else is hearing those little sweet spots and doing something with them emotionally. But when I heard what Devin did, it was so obvious to me that not only was he able to hone in on these very intimate kind of sweet spots, but what he did on those exact moments with his voice just was better than anything that I think could've happened if I was sitting there going, “Okay, now try this, try this." When I got the piece back, it was a total overhaul of my perspective of everything.

Townsend: In addition to the trepidation of revisiting something that had a profound emotional impact, there was a sense of, “If we're going to do it again, this is where things have evolved to. This is the point where I am as a musician and a person, and where you are as a musician and a person. Can we make this work in a way that pays homage to the original experience between us while incorporating where we've gone?" And for me it was like, “Let me do it on my own. Do it in a way where I could hear my voice with consideration for that fact that I don't want to shy away from what it is that you're trying to achieve."

Devin Townsend was just 19 when he was called upon to lay vocals for Steve Vai's Sex and Religion. They've reunited on Vai's latest album, Modern Primitive, on the track “The Lost Chord." Photo by Christie Goodwin

Charupakorn: Have the advances in technology changed your music writing and recording process?

Townsend: It's two things, right? On one hand, it gives you limitless options, but if you're hardwired to want to get things perfect all the time, that could lead to being a liability. I have five guitars that are in different tunings and they all have the EverTune bridge on there so they're always in tune. I've got a heavy patch, a clean patch, a dirty patch, one vocal mic that goes into one chain. I've got maybe three or four delays, and a big massive Pro Tools screen with a ton of power. It's all plugged in and ready to go. Like, I never, ever second guess it. So as a result of that, I power through things. If someone said to me, “Here's a bunch more options," all that really does is confuse the objective, at least for me, and I think you can get lost in it.

Vai: That makes a lot of sense and I've seen that happen to myself because I'm always getting gear, and I'm interested in trying out things. It can belabor the point. Technology is going to continue to evolve, and the way we make the music—the way we mix it, the way we deliver it, the way we purchase it, the way we listen to it, the way we consume it—it's all going to continue to change. The one thing that doesn't change, the thing you'll always need, is an artist or creator to have some kind of inspiration.

to take it lightly." —Devin Townsend

Townsend: A vision.

Vai: Yeah, a vision. And in some respects I do limit myself from exploring too much technology because it is a black hole. Of course, somehow I get by with whatever stuff I'm using when it's there. As far as anything different this time, with the guitars I always try to take a different approach with the solos each time, where I say, “Okay, what are you going to do now?

You've got to come up with something you've never done that has some cool value in it." Usually that's all phrasing, because I've done the fast guy thing and now I'm focused more on phrasing. That's what this record has. From a guitar player's point of view, there's a lot of nice depth to it.

I'd like to now comment on your record, Devin. I've followed your career and there's always this very interesting metamorphosis that's taking place in your whole creative output, and there's great variety, too.

Devin Townsend's Gear

GuitarsFramus signature Stormbender

Framus T-style

(Both guitars have Fishman Devon Townshend Signature “Transcendence" pickups and EverTune bridges.)

Amps

Fractal Audio Axe-Fx

Mesa/Boogie Dual Rectifier

Kemper Profiler

Effects

Fractal Audio MFC-101

GigRig G2 switcher

Sonic Research strobe tuner

Source Audio Nemesis Delay

MXR Echoplex Delay

Solid Gold FX Stutter-lite tremolo

Strymon TimeLine

Red Panda Particle delay/pitch shifter

MXR Reverb

Greer Lightspeed Organic Overdrive

Seymour Duncan Vise Grip Compressor

JHS AT (Andy Timmons) Signature Channel Drive

ZVEX Fat Fuzz Factory

EarthQuaker Devices Dunes overdrive

Teese wah

Strings and Picks

D'Addario (.010–.052)

Planet Waves, Evidence, and Providence cables

Line 6 Relay G70 wireless

Dunlop custom pick based on .73 mm Tortex

Planet Waves bass straps

Dunlop Straploks

Within the variety, there's still the thread of your voice. Whether you're doing an ambient record or

a quasi-country record, there's an effervescence to it, of melody and your production sound. It all beautifully wraps. One of the things I noticed most is your music, for you, is so deeply rooted with

your personal transformation through life. For instance, the way you opened it with “Truth." [Editor's note: “Truth" is a remake of a track from Townsend's 1998 release, Infinity.] For me that song, perhaps more than any song in your catalog, just explodes. It's so interesting that you revisited it, re-recorded it so that you can come to terms

with where you're at now and what that song means to you now, and then pave the way for the rest of the record with your new perspective on who you are and how you're moving forward. The music is almost like a consequence of your inner reflecting.

Townsend: One-hundred percent. Thank you, I appreciate that.

Vai: It's penetrating, Devin. What you're doing, many of your fans are really getting—especially how you relate it to your personal growth. Some of it's so interesting to me because there are parallels with the way I perceive myself grow. One of them

is in “Truth"—how it's a spiritual awakening for you. That a surrendering to the ignorance of the mind reveals the truth. Just even saying that, which is what you had written, there's so much wisdom in that, and I feel that in the song.

Townsend: The reason “Truth" and “Transcendence" are on there, and the conversation about spirituality or religion, is because I had to take a year off from touring.

Being a lower, mid-tier prog metal act is a dubious profession when everybody's on salary [laughs], and I got presented with the opportunity to write a book. My first thought was, “Man, I'm in my mid 40s. What am I going to write about?" It's not going to be like Mötley Crüe, snortin' ants off whatever. In the process of going through it, and the work of starting with a ghostwriter and then ending up writing it all by myself, it became very clear that by objectively seeing your past, to make it of any value for a reader, it has to be less about pontificating and more about “this is where it's at." And you start seeing patterns emerge, or at least I did, and when these patterns consistently pointed to something that I was not satisfied with, you're either stuck in that situation of continuing it for the sake of feeling sorry for yourself as some sort of creative outlet, which is pretty gross, or sort of incorporating: “If these patterns have resulted in X, and X is something that I no longer want to participate in, what can we do in order to change it?"

Charupakorn: Can we expect more collaboration in the future?

Townsend: Yeah. I think we're starting today.

Vai: There's always that possibility and I would love more than anything to work with Devin on stuff, and we have, sort of, through the years. We've kicked around the idea of doing something a little more formal. So at this point, we kind of threw it into the universe and if it happens, it would be fantastic.

Townsend: I agree.

YouTube It

Watch a flashback of Steve Vai and Devin Townsend from the Sex and Religion era. Even within the restrained setting of The Tonight Show studio, Vai and Townsend bring their A-game for this performance of “Still My Bleeding Heart."

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)