The origins of Aziza, a collective jazz supergroup of sorts, started back in 2014 when legendary bassist Dave Holland and saxophonist Chris Potter were brainstorming for a project to tour with in 2015. “I just love playing with Chris,” says Holland, who brought Potter into his funky and soulful quintet in the early 2000s. After bouncing some ideas around, the duo decided to bring in guitarist Lionel Loueke and drummer Eric Harland. “Lionel approaches the instrument in a unique way and blends his African heritage and guitar styles with all the language and harmony of jazz music.”

None of the members were strangers: Loueke and Harland had spent time in trumpeter Terrance Blanchard’s group, and Holland, Loueke, and Potter all worked with pianist Herbie Hancock on the tour for his Joni Mitchell tribute project, The River. The tour was an immediate success with each member bringing in specific compositions for the band. “From day one, it was just all about the music,” says Loueke. “You’re playing with musicians that just listen so closely to whatever you’re doing and are very open-minded. We’re ready to take some risks and see where the music takes us.”

Halfway through that first tour, the band decided that their intense interplay and chemistry needed to be documented in the studio. The group booked two days at Sear Sound Studio, and each member brought in a pair of compositions for what became their self-titled debut. By now, the tunes had been road-tested with twists and turns added to each. One of Holland’s contributions, “Finding the Light,” is an introspective, odd-time piece built around a slightly off-putting ostinato that provides a joyous platform for Potter’s soprano sax flourishes. “I wrote a counterline specifically for Lionel,” says Holland. “I wanted it to be a layered thing.”

It was one of Loueke’s compositions, “Aziza Dance,” that gave Holland the idea for the name of the group. During the original tour, Holland took Loueke aside and asked him about the origins of the name. Loueke explained that Aziza is the name of a god of inspiration taken from Dahomey mythology, which is from his homeland of Benin. “It just sparked me,” says Holland. “I thought it would be a wonderful name for the band.”

When we spoke with Holland and Loueke, they had just finished a lengthy European tour. We asked them to describe recording Aziza and what it takes to channel their worldly influences into one of jazz’s most electrifying quartets.

Once the band members were selected, what was the overall vibe you had in mind in terms of composing for Aziza?

Holland: It’s the players involved. When we were all considering what music to bring in, we were really thinking about an idea of what the four of us playing together would sound like—even though we hadn’t heard it. We’re writing music for improvisers. We’re thinking about how each person approaches their instrument, what their concept is, and what language they like to explore. Then we try to find compositional vehicles that allow for the maximum amount of freedom for those players.

Loueke: You don’t have to write much for this band. “Aziza Dance” was written for my trio, but I knew that with these players, it would go in a whole different direction. That makes it easy, yet sometimes very challenging because you don’t expect something that works one night to be the same tomorrow. We’re thinking of doing a live recording because it’s a whole different energy. When you play the same music every night for six weeks, it just keeps growing into different shapes and never goes in the same box or direction.

Speaking of “Aziza Dance,” the tones you’re getting on the intro and solo are wild. What were you using there?

Loueke: I use a Kemper Profiler. On that patch, I used my regular sound with a lot of wah and two types of whammy. One is an octave higher to make the chords a little fatter. For the intro, I used that plus a whammy setting that bends an octave down. That gives me flexibility. The idea was to imitate the sound of a talking drum. I also have a ring modulator with different frequencies connected to the expression pedal. There’s a kind of crossfade between the whammy octave down and ring modulator going up. I think on the intro, I probably opened up all the patches!

Holland: The groove of “Aziza Dance” is just fun to lay into and explore. We look for new ways to bend it around and interpret it.

Dave, the fuzzy bass sound on “Sleepless Nights” seems a bit out of character. What’s the story behind that song?

Holland: Back in the day when I was with Miles, I had a fuzz/wah pedal I used on the bass guitar. I’ve worked with my engineer, James Farber, since the late ’80s, and every now and then he’ll say, “How about the fuzz on this one?” It’s a running joke at this point. But on this particular tune we tried it, and I liked it. But instead of a pedal, he used some kind of Pro Tools plug-in.

Loueke: I wrote this tune based on an application I did for iOS about African guitar styles, called GuitAfrica. I did some research based on different traditional instruments from different places, and I wrote some new tunes and grooves. By doing that research I learned a lot about the gimbri, which is a traditional instrument from Morocco. It’s something between a guitar and a bass. When I wrote that tune, I had the gimbri tone in mind, so I tuned my low string down to D and basically played the whole intro on that one string.

YouTube It

Taken from a stop on Aziza’s inaugural tour, this full-length set features four tunes from their self-titled album. Don’t miss Lionel Loueke’s wicked, effects-laden intro to “Aziza Dance” at 21:45.

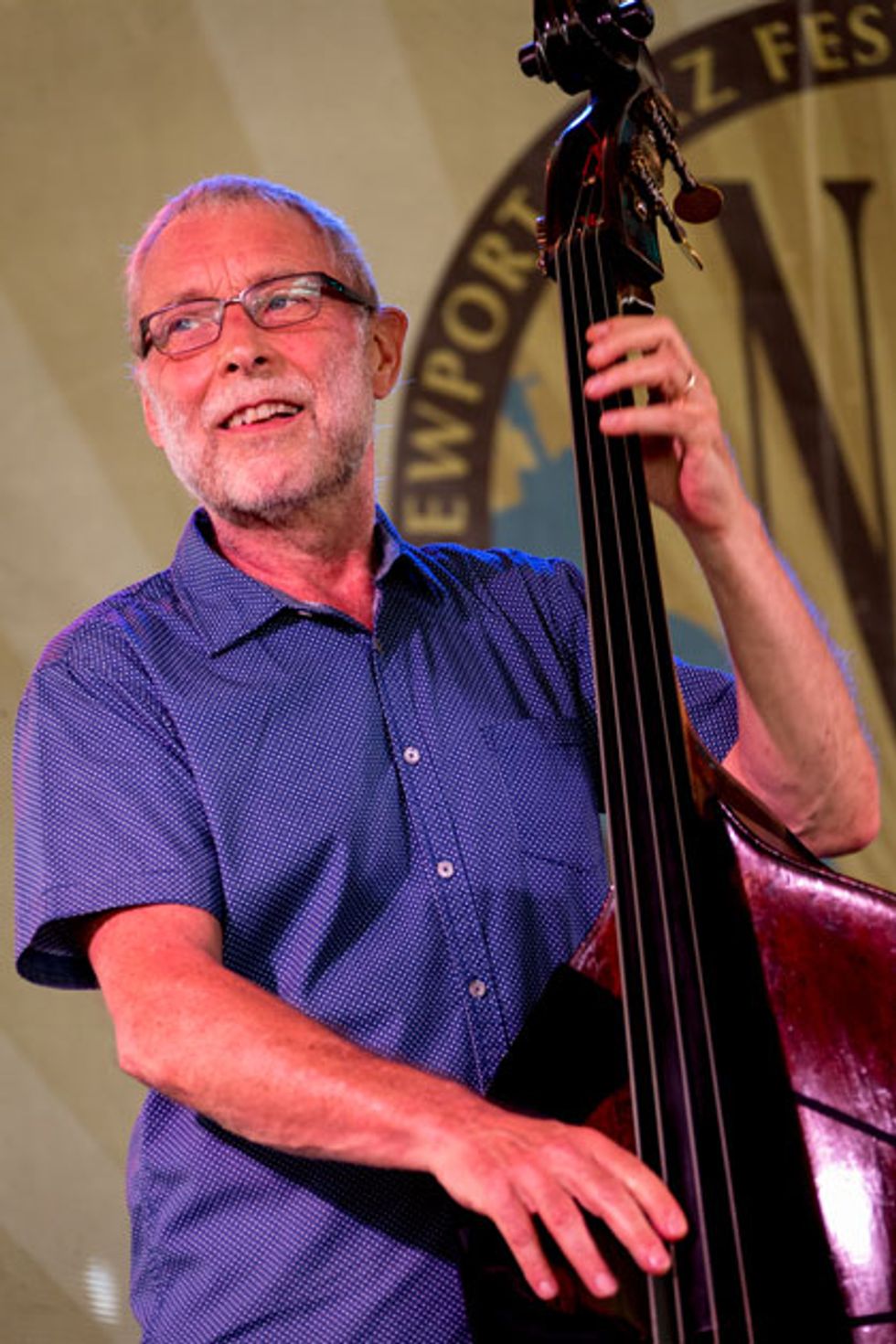

“From day one it was just all about the music,” remembers Loueke, shown here with Aziza at Rhode Island’s fabled Newport Jazz Festival. “With these guys, you don’t have to say much—it just takes off naturally.” Photo by Douglas Mason

In terms of composing, Aziza is a true collective. With such an accomplished group of musicians, how do you communicate your vision of your compositions in the studio?

Holland: Sometimes we had individual parts or just lead sheets. I think we all had the same approach—what’s on the paper is merely a suggestion or starting point. Speaking for myself, I’m wide open to any kind of interpretation these wonderful players bring to the music. Very often, what they come up with is much more than whatever I could have thought of. It’s just a matter of postulating a starting point. The less you write, the more opportunity you offer for the creative power of the group to come through. I think Miles demonstrated that beautifully in the things he put together. There would often be a minimal amount of written material, but conceptually, the material would be very strong. Then he would find the right people to come in and fill up the gaps with their own creative ideas.

Loueke: With these guys, you don’t have to say much—it just takes off naturally. The tempo might be different or someone could come up with an idea that’s best for the song in that moment. That level of focus and embracing the music is important.

Dave Holland’s Gear

Basses

• Vintage French upright bass

• David Gage Czech-Ease Road Bass

Amp

• Gallien-Krueger 200MB

Pickups and Accessories

• David Gage Realist pickup

• Underwood pickup

• Klark Teknik DN 100 DI

• DPA d:vote 4099B mic

Lionel Loueke’s Gear

Guitars

• Sadowsky Semi-Hollow

• Private Stock PRS Singlecut Archtop

Amps and Effects

• Kemper Profiler

Lionel, you mentioned that you’re using a Kemper. Any digital all-in-one unit can be a real wormhole sometimes. Where does your tone start in this context?

Loueke: As you know, for most guitar players, sound is a big deal. When I got the Kemper, I tried to get all the analog sounds from the pedals I had. The magic thing about it for me is to find the right amp profile. I basically use two amps on the Kemper: an AC Morgan, mostly for the distorted sounds, and then I use another Morgan for clean sounds. It depends on what effects I’m using on top of the amp. I also use some stereo reverb, delay, and a phaser, but you can’t really tell because the mix is very low.

Do you use the Kemper for gigs and recording?

Loueke: Yeah, for this album I took a direct stereo out from the Kemper. When I use it live, I have a Mesa/Boogie 4x12 onstage. Sometimes that can scare people, but I’m not one of those guitarists who plays loud. For me, it’s more about the range of the cabinet. I don’t crank it, but at least I get a fat sound. Also, I mostly used my Sadowsky on the album, but I have a few PRS guitars, too. It just depends on the gig.

Dave, tell us about the upright bass you used on Aziza.

Holland: I’ve had my current bass since about 1995. I found it in an antique shop in France. It had been in a café that had been closed for about 30 years. The antique shop owner had bought the entire contents of the café. I was just taking a walk before leaving for the next gig when I saw the bass in the window and took down the number. A few weeks later I was back in the area and managed to see the bass and try it out. I thought it had a lot of promise, so I brought it back to New York and had David Gage renovate it. We believe it’s about 200 years old and of French origin, but there’s some discussion about that.

That’s so interesting that it’s not some high-end boutique instrument you sourced through a music store.

Holland: Yeah—there was something about the way it looked. It has very narrow shoulders, but a very deep bout. I thought the instrument had quite a potential for some real depth of sound. When I tried it, it certainly seemed that way and worth taking back to New York to find out how good it could be.

Do you bring it out on the road?

Holland: Until about nine years ago, I used it for everything. That was around the time when the airline started to change their policy about checked baggage. I was increasingly having problems with them checking it and I’d been struggling with it for a while. Then I discovered a travel instrument that David Gage designed called the Czech-Ease bass, and now that’s what I’ve been using on any gig I can’t drive to.

What’s your amp setup like?

Holland: I use two Klark Teknik DN 100 DIs—one for the David Gage Realist pickup and the other for an Underwood pickup that feeds my Gallien-Krueger 200MB onstage. The Klark DIs are wonderful. I also use a DPA d:vote 4099B bass mic.

Both of you have a reputation for making odd-time signatures very accessible. Lionel, do you think that came from years of listening to traditional African music?

Loueke: Yeah. Personally, I don’t like odd meters that make me feel like I’m doing physics or math. When it comes to composition, my process is that after recording 5 or 10 minutes of music, I go back and listen to it and find something I like. Then I figure out what meter it’s in. It just happens naturally. If something comes out at 21 1/2, then that’s what it’s going to be. If the bass line comes first, then I’ll use GarageBand to find a groove that is slightly against that bass line to give me some sort of cycle, or circular vibe, so it doesn’t sound like a skipping CD. Which can be a challenge—I spend a lot of time making the groove really sound natural.

Growing up in Benin, was there any sort of formal music education?

Loueke: It was all intuitive. There were no schools to go to—I just learned by playing traditional music. I grew up playing percussion and then played bass for a while before moving to guitar. I’ve always said I’m a frustrated bassist and percussionist, and that’s why I beat on the guitar.

Dave, I must ask about that famous story of the jam session you had with Jimi Hendrix. How did that come about?

Jimi had Electric Lady Studios in the city, and I got a call one day to go down there for a jam session with John McLaughlin and Buddy Miles. It was just the four of us in the studio and an engineer. There was no real plan, as far as I could tell. Jimi would just start up a riff and we’d pick it up and jam on it. We were playing a lot of the same festivals at the time, so our paths did cross a bit. I wasn’t a close friend or anything, but I was a huge fan. He loved Miles Davis and Miles loved him, and there had been some discussion of them doing something together, I think. Unfortunately, that was cut short. He was clearly moving on and looking for some new directions, and I think that was just a chance to try something out.

YouTube It

Here’s the result of Dave Holland’s only time jamming with Jimi Hendrix. It’s a free form instrumental affair with the legendary John McLaughlin on guitar and Buddy Miles on drums. Shortly after this session, Hendrix went on to form the Band of Gypsys with Miles and bassist Billy Cox.

During the group’s featured set at the Newport Jazz Festival, Dave Holland plucks away on a 200-year-old French bass that he found in an antique shop. Photo by Douglas Mason

Dave Holland’s 6-String History

Even a cursory glance at Holland’s extensive and impressive discography makes it obvious that he enjoys collaborating with some of the most revered guitarists of our time. It’s no surprise, considering his roots weren’t based in the low end. During the early ’50s in England, Holland was swept up in American rock ’n’ roll, and he soon found himself playing in a skiffle band that mixed elements of rock and folk. “My first bass was a skiffle bass made out of a box, broomstick, and a piece of string,” remembers Holland. On his 10th birthday, he received a guitar and started to learn popular songs on the radio. By 13 he had shifted to bass. PG asked Holland to share memories of playing with some of his best-known 6-string collaborators.

Jim Hall

I didn’t do much recording with Jim, but we did some duo things together. I’m hoping someday those recordings can come out. I first heard him live in ’65 with Jimmy Giuffre in London. It wasn’t until we connected in New York in the ’90s that we really started to play together.

Derek Bailey

I met Derek in London in the mid ’60s and he had quite an extraordinary conceptual idea of the guitar. In fact, I heard him in ’62 before I knew who he was. When I was 17, I happen to be on tour with a big band. We stayed in a hotel where a guitar trio was playing this Bill Evans-influenced music. I found out much later that it was Derek. By the time I got to know him and play with him he had developed this completely unique language. He had a tremendous impact on the open-improvisation scene in London.

John Abercrombie

I first heard John in the late ’60s. Jack DeJohnette brought us together in the Gateway trio and we had many, many great years of playing together. John really thinks outside the box and has a very personal sound that is completely steeped in the tradition.

Kevin Eubanks

During the ’80s I was running the Banff school [the summer jazz workshop at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity in Alberta, Canada] and one year Abercrombie couldn’t make it. Robin Eubanks recommended his brother Kevin who was already coming up to Banff. From the very first day we played as a duo, I had this immediate connection with him. I asked Kevin if he’d be interested in working together and that resulted in the Extensions album.

Pat Metheny

We first met around the time of Bright Size Life. Pat had asked me to do that album, but because I was working with Sam Rivers I wasn’t available. That’s probably the best thing that could have happened because who could be better on that album than Jaco? We didn’t get a chance to play together until the Parallel Realities tour with Jack DeJohnette. What Pat has accomplished is quite extraordinary.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)