Tim Commerford's new band, Wakrat (pronounced “wokrat"), recently staged a protest in London in response to the Brexit vote, where they attempted to establish the “Republic of Wakrat" by planting a flag in Parliament Square's center. Last year Commerford lit himself on fire in Future User's “Mountain Lion" video. Back in 2000 he climbed the stage scaffolding at the MTV Video Music Awards in objection to Limp Bizkit winning the Best Rock Video award over his then-band Rage Against the Machine. Simply put, Commerford is a fierce, honest individual who wears his heart on his sleeve and likes to shake up the establishment.

From RATM's “Killing in the Name," with its “Fuck you, I won't do what you tell me!" call-to-arms chorus to Wakrat's recently released second single, “Generation Fucked," Commerford always seems to be in a band with a strong message. Though you'd think it takes a certain amount of acumen to launch an activism-motivated musical act, Commerford insists he's never had any preconceived notions of what he's going to do musically or otherwise. “Opportunities present themselves, whether it's Rage Against the Machine or Future User or Wakrat," he says. “It's just about going in a new direction."

Despite such uncalculating methodologies, Commerford has already captured lightning in a bottle twice in his career—first with RATM and again with Audioslave. His muscular, riff-oriented bass lines with RATM, the foundation of songs like “Bombtrack," “Killing in the Name," “Bullet in the Head," and “Calm Like a Bomb," have become such a part of the canon that they are as commonly played in music stores by aspiring bass players as “Stairway to Heaven" or “Enter Sandman" are by young guitarists. With Audioslave, there was less social commentary, but the music was no less potent. Commerford's playing on “Show Me How to Live," “Like a Stone," and “I Am the Highway" is more nuanced, the ultimate lesson in refinement—less is more to the nth degree.

—Tim Commerford

Last year Commerford launched a series of music videos (and ultimately an album via iTunes) under the banner of Future User, mixing EDM, prog, and his deft bass playing into a sound he dubbed “progtronic." It was a less high-profile, but equally compelling, studio-only project, exploring different genres of music than what he'd previously been associated with, and it revealed a lot about Tim's influence on his other outfits—the overall fierce attitude and socio-political messages behind RATM are present in songs like “Mountain Lion" and “Clockwork," for example. “I'm proud of the amount of music I've been able to contribute in Rage and Audioslave, and I like to think I'm a little bit unsung," he says.

Now comes Wakrat. Structurally, it's a completely different animal from any of Commerford's other bands, but it still features what's becoming his indelible imprint. The grooving, mammoth bass tone is unmistakable, but instead of channeling hip-hop grooves through the lens of hard rock, on Wakrat Commerford takes on jazz-inspired odd-time signatures and plays them with a punk-rock attitude. In songs like “The Number" and “Nail in the Snail," his bass snakes its way through frenetic timing, providing a melodic counterpoint to the mechanical precision of guitarist Laurent Grangeon and drummer Mathias Wakrat. Upon first listen, it would seem that the bass is the catalyst for the music, but it's actually Laurent and Mathias, both French nationals, who generate most of the material.

“Wakrat was not an idea of mine," Commerford candidly admits. “It was just being in the right place at the right time. So much of music and being a successful musician is luck, and I just got lucky." Despite this humility, Wakrat proves yet again that Commerford has been one of the most forward-thinking, influential figures in the bass community over the past three decades.

As he prepares to hit the road with the newly formed Prophets of Rage, it's an especially big moment for Commerford, as Wakrat will play an opening set on the tour. It's proving to be a welcoming challenge for the bassist, who will also sing in Wakrat while playing technically difficult bass lines. “In a couple of months, I'll be the best bass player I've ever been," he says. “I'm never going to be Jaco, but I'm going to be the best Timmy C ever."

Commerford recently returned to playing Music Man basses. “I love Bernard Edwards and Louis Johnson and I grew up playing StingRay basses, but I hadn't played one in a long time. I love the way it feels."

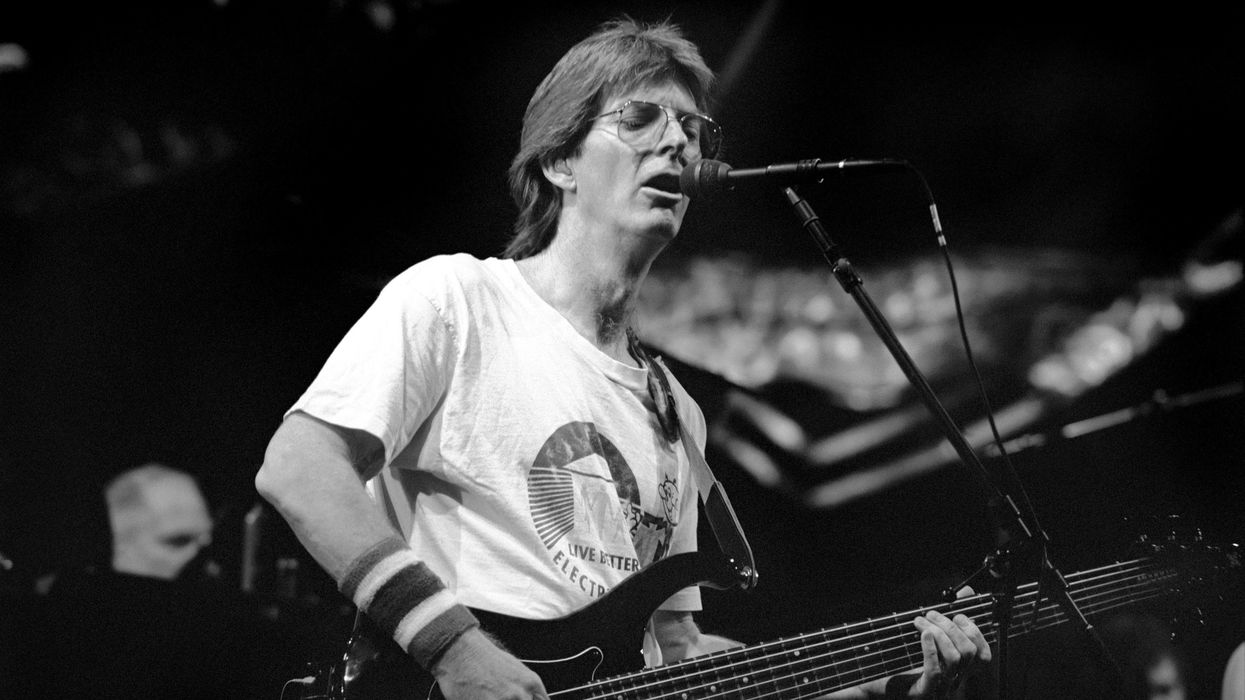

Photo by Travis Shinn

Is it important to you that your music is socially relevant, lyrically speaking?

We have a wide spectrum of song topics, but they all come from the heart. “Generation Fucked" is sort of about the world we live in today, but it's really inspired by reading Plato's Allegory of the Cave and feeling like, “Wow, that's the world we live in." We're chained in a cave and we're seeing shadows on the wall and we're not really seeing what's behind those shadows. Maybe we don't even want to know.

How challenging is it nowadays to launch a new, original band like Wakrat?

It's never easy to play original music. It's always going to feel uncomfortable. Back when Rage first played, and we were mixing metal and punk with hip-hop, no one else was doing that, but we never worried about it. We just did it because we liked it and it worked out. I feel that same uncomfortable feeling in Wakrat. This music is like nothing else that's happening right now. Are people going to dig it? If they don't, that's fine. Every single song is full of cursing and if people don't like that, the lyrics are for them. That's how I feel. In “Pigs in a Blanket" the chorus is, “Fuck with me and I'll kill you all." I love that.

How did you meet Laurent and Mathias?

Through Zack de la Rocha. Mathias owns a restaurant in Eagle Rock and Zack lived right next to it. He knew that Mathias rode mountain bikes and said I should ride with him, so I did. I got to know him and I started inviting him over to my house for Thanksgiving and Christmas, and the next thing you know he's telling me he's a drummer. I never really took him seriously and then one day he came at me with some music that he and Laurent had recorded. It was actually great—it reminded me of the punk music I grew up on like Bad Brains, Fugazi, and Helmet. It also delves into jazz, which I love. I was blown away by the intricacy of the time signatures and the heaviness of it and how different it sounded.

Why is the band named after Mathias?

It's sort of like Van Halen or Fleetwood Mac or the Police. Stewart Copeland formed the Police and I believe his signature style on the drums shaped the sound of that band. And Mathias is exactly the same. His signature drum style shapes the riffs and the music we play. It's his brainchild. He put the band together.

Did you immediately hear how you would insert yourself into what was going on musically?

No. I couldn't really wrap my head around it at the start. I would listen to it, but it was super hard for me to figure out. I initially record the music in pieces using Pro Tools. I would play it for Laurent and Mathias asking, “How do you guys feel about this part for the verse?" I did the vocals in the same way. After doing it that way, we learned to play the songs as a band and I was able to sing and play them. I then said to Laurent and Mathias, “Now that we know these songs, we should play them authentically and honestly and record them from start to finish, sing them from start to finish." So we rerecorded the music and that's what we're now putting out. It's hard to play, but I figured it out.

So, you rerecorded the entire record?

Yeah. I was able to sing the songs on our demo recordings, which were a half-step higher [the video for “Knucklehead" features music from the demo version], but I would blow my voice out every time. I wouldn't be able to talk for a couple of days afterward. And then when we went to play them live I quickly realized the key signatures were too high. Now we detune a half-step, so we do dropped D tuning down to C#. Bringing it down that half-step really made it a lot easier to sing.

On Wakrat, Tim Commerford played his Lakland Joe Osborn Signature bass strung with Rotosound Tru Bass black nylon flatwounds. “The ones Paul McCartney used," he says. “It's a cool sound." Photo by Travis Shinn

Were you able to finesse other aspects of the music by that point?

Mathias is a machine on the drums, so his parts sound just as good on the demo as they do on the record. But I think that Laurent and I were actually able to dial in our tones a little bit more. Initially when Laurent and Mathias wrote the arrangements they didn't have a bass player. Laurent plays a baritone guitar, so a lot of the bass in their music came from the guitar, which was a blessing sometimes. I could play higher parts and feel like the low end was covered, but then other times, when I wanted to rock as a bass player, I felt like he was stepping on me. We were able to weed that out and better find our place in the music.

This is your first time singing lead and playing bass, correct?

I did a little project before [Future User], but this is the first time I've ever tried to sing and play live, and actually do it honestly and bring it out. It's interesting how being a bass player and trying to sing can make you a better singer and being a singer and trying to play bass can make you a better bass player. No doubt it's from learning when to breathe and discovering other little tricks. I do a lot of practicing singing and playing, and the other day I just discovered a new little trick. I did a pull-off and thought, “Oh, I can breathe right here and that makes it easier for me to sing this next part and play that part." It's a puzzle and I like puzzles.

When you're not playing live, how do you stay in shape, musically speaking?

I play unamplified all the time. I just use my electric bass and pluck the strings hard enough to be able to hear myself acoustically. That's the way I've always done it and I've always felt it has benefitted me.

Does pulling double-duty on your upcoming tour with Wakrat and Prophets of Rage present any unique challenges for you?

I have 40 songs that I have to know and have my head wrapped around completely. I've never had to think about that much music going into a tour, so that's required a lot of home-time practicing, singing, and playing.

What differences between the two bands can people expect when they see you live?

I don't think they step on each other, physically or musically. My brain is challenged to play Wakrat music. With Prophets, it's more of a physical thing. It's more like an aerobics class. It's jumping around, whereas with Wakrat I'm on the mic the majority of the time. They feel totally different. Tempos are different. Styles are different.

Describe your right-hand technique and how you attack the strings.

I grew up using three fingers. I was into Duran Duran, Rush, and Iron Maiden—I love Steve Harris—and for me, playing those galloping parts required three fingers. So back then I used three fingers all the time. [Editor's note: Steve Harris uses only two fingers.] Then when I got playing with Rage, I was more diehard—I felt like it was more solid to play with two fingers. So with Rage I did everything with two fingers. And now with Wakrat, the tempos are too fast for me to be able to do it with two fingers, so I had to bring the third finger out of retirement.

So, if you're playing four-note patterns with three fingers, does that mean you land on a different finger for each downbeat?

We don't do any galloping triplet parts in Wakrat. It's all fast 16th-notes, so I'm leading with a different finger every single time. That's the thing I focus on. At the end of each riff I know what finger I should land on and if I don't, I know I did something wrong—that and breathing. I know when I should be taking a breath for singing and when I should be landing on my index finger, and if everything works out accordingly, that's how it should be. And if it doesn't work out like that, I've done something wrong.

It must be challenging to sing and play fingerstyle bass parts. Most singing bassists seem to use a pick.

For some reason it's easier for me to play intricate parts using three fingers and sing over the top than it is to play those same parts with two fingers. I don't know why. I see guys who play bass with a pick and sing. The pick is more of a percussive tool. There are not a lot of bass players playing with their fingers who are singing. It's like an extra appendage or something, like having three arms and two legs.

Tim Commerford's Gear

BassesMusic Man StingRay HH (Wakrat)

Music Man StingRay HS (Prophets of Rage)

Lakland Joe Osborn Signature

Amps

'70s Ampeg SVTs (four)

Ampeg SVT-2PRO (for distortion)

Ampeg 8x10 cabinets

Effects

Homemade overdrives

Marshall The Guv'nor

Dunlop 105Q Bass Wah

Aphex Punch Factory

MXR Phase 90

Custom ABY amp selector

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Slinky Bass (.050–.105)

Rotosound Tru Bass RS88LD black nylon (.065–.115)

What basses did you use on the record?

I recorded Wakrat with Lakland Joe Osborn Signature jazz basses strung with Rotosound Tru Bass black nylon flatwounds—the ones Paul McCartney used. It's a cool sound and I was planning on using that live, but somewhere along the way I got approached by Ernie Ball to play Music Man basses. I love Bernard Edwards and Louis Johnson and I grew up playing StingRay basses, but I hadn't played one in a long time. So Ernie Ball gave me one and it sounded perfect. I love the way it feels. I did make some modifications. I used a Dremel and ramped the pickup screw mounting points down and put a thumb rest on it.

Are you using flatwounds live?

No. I'm using roundwounds. They're more raw-sounding. It gives the overdrive a little more fur

and fills in the blanks a little better. And they stay in tune much better.

What about amps? Are you still using Ampeg?

I have four '70s Ampeg SVTs and several SVT-2PROs for the overdrive. They're tube heads that have a gain and drive knob on them.

You've become kind of synonymous with using distortion on bass.

I never used distortion on bass until the first Rage record. I used a Marshall The Guv'nor pedal with one amp. When we made the second Rage record I decided I needed to have an amp just for bass and then another amp that comes on when I use distortion—it adds to what's there instead of the low end dropping out. And that led me into ultimately tinkering with pedals and just geeking out.

You're kind of notorious for tinkering with your amps, too.

I love old Ampeg SVT heads. I absolutely love them. And the cool thing about them is that they all sound great, but they all sound different. And it's because they were handmade with those old GE tubes, which have a signature sound. So I would get some Sovtek tubes, some Groove Tubes, and some GE or Sylvania tubes and experiment with each brand to see what difference they make. And then I discovered that 30-watt tubes actually sound way different than 35-watt tubes, and I didn't even know I could put 35-watt tubes in until I did it.

Did you have any prior knowledge of electronics?

I took some electronics classes in college and I can get my way around resistors and different things. I was just experimenting. I have a couple of distortion boxes that I made. I Frankensteined parts from different pedals into one pedal and every time I go to make a record I always try to exclude that pedal. And when I do, it sounds good, but then I'll put that pedal on and it sounds better, so I end up using it [laughs].

YouTube It

Wakrat plays “Knucklehead" off their self-titled debut at L.A.'s Bootleg Theater in late 2015. Watch Timmy C's passionate punk and prog-infused performance, notably his three-finger bass breakdown at the one-minute mark.

What inspired you to use distortion in the first place?

I initially started using distortion because I hate the sound of rhythm guitar. I never wanted Tom Morello to go back and put rhythm guitar underneath his guitar solos. I just think that sounds like heavy metal and I just don't like it. And so, I use overdrive to sort of take the place of the rhythm guitar. With Rage it was the fifth member and with Wakrat it's the fourth member. It's the invisible rhythm guitar player that hypes everything up.

You studied jazz for a while. What impact did that have on your bass playing?

I learned how to work my way around the neck using the modes. I played upright with fingers, as well as a bow, and I was pretty authentic, using the whole side of my finger. I realized how much of a sport it was and how much muscle it takes. It's a hardcore thing to do. I haven't played the upright in a while and I couldn't break it out right now and just start playing. I would quickly get blisters up the side of my finger. There'd be a long period of relearning the instrument because it's just so athletic.

Did you study any artists in particular?

I love '60s bebop jazz—Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Pharoah Sanders—and I look at John Coltrane as the greatest musician that ever lived. I'll never be a player like that, but I can appreciate it. There have been parts in Rage songs, like the beginning of “Bulls on Parade"—that's just lifted from Coltrane's “My Favorite Things." I was like, “I can alter that a little bit and make it super heavy." There are a lot of things like that that I've taken from jazz. Now here I am in Wakrat where most of Mathias' patterns are really jazz-oriented. So, thankfully I have some understanding of it.

What advice do you have for that kid out there who's in his or her first band or who's about to pick up an instrument?

Get together with your friends, with people you respect and are inspired by, and play music. If they're not the best players that doesn't mean that's not the best choice. It's not the best players that make the best bands; it's the best chemistry that makes the best bands.

Wakrat guitarist Laurent Grangeon puts his pedals to the metal. Photo by Travis Shinn

Driven!—Wakrat's Laurent Grangeon

Born in France, Laurent Grangeon wanted to play guitar, but the music industry there just didn't inspire him. “It was airtight, closed, and pretentious," he recalls. “So I just left." He set out with nothing more than a bag of belongings, his guitar, three nights booked in a hotel, and no permanent address. He chose the U.S. as his destination simply because a lot of the music he was listening to at the time came from the States. Los Angeles, the city he now calls home, was basically a random choice. “The rest is history," he chuckles. Though he and drummer Mathias Wakrat are both from France, they actually only met for the first time in L.A. 10 years ago, at the restaurant Mathias owns. “We do have a lot of similarities—we took the same type of route in a way," says Grangeon.

Laurent Grangeon's Gear

GuitarsMusic Man John Petrucci BFR6

Amps

Rivera Knucklehead Reverb 100

Ampeg B42X (modded by Tim Commerford)

Fender Bassman 50 (modded by Tim Commerford)

Bogner 4x12 cabinets with Celestion Vintage 30s

Effects

Fulltone Bass-Drive Mosfet

DigiTech Whammy (5th Generation)

Electro-Harmonix Stereo Talking Machine

Line 6 M13 Stompbox Modeler

RJM Mastermind PBC Programmable Pedal Switcher

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Power Slinky (.011–.048)

Ernie Ball Baritone Slinky (.013–.072)

Dunlop 1 mm Tortex

Grangeon cites the Police and Bob Marley as early musical favorites while he was growing up, but he didn't start playing guitar until he was in his early 20s. He eventually got into the Cure and Depeche Mode, then into the Manchester scene, specifically the Stone Roses. Later on came the Pixies and Seattle's grunge era, but he says that sounds, not bands, are essentially what drew him to the instrument. “I wasn't really into any one type of music in particular," he says. “I was just into sound—effects pedals and gear." Grangeon has employed all kinds of effects over the years, including phasers, delays, and chorus pedals, but relies more heavily on ring modulators and filters to help craft Wakrat's voluminous soundscapes. “They just sound different and the opportunities are endless when you use them properly."

At the heart of Grangeon's setup is what he refers to as his “tri-amp" rig. “I have a Rivera that is always my backbone," he explains. “It's just a mean, crunchy, punchy sound with nothing on it. Then I have two other amps where I send all kinds of different effects." His effects are a combination of analog and digital gear, but live he relies on an RJM Mastermind PBC as his main controller. “I use a lot of MIDI because of the tri-amp setup and I like to recall effects at any time without having to tap dance. The RJM simplifies everything."

Aside from the obvious impact effects have on their musical identity, speed is another key element of Wakrat's sound. Laurent emphasizes the songs are powerful because the band is tight. “We own the click," he says. “You can't be fluctuating—up-tempo music has to be super tight or it doesn't sound right." And they don't just record to a click, but rehearse with one, too, often playing around with tempos, even speeding songs up until they're too fast and not grooving anymore. “It's just a curiosity," he says about driving tempos to their brink. “If we have a good groove we'll try it faster just to fuck with it to see how it sounds. Sometimes it even grooves better and sometimes it doesn't, but you have to try to know. We are definitely driven by fast music."

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.