Cedric Burnside began touring when he was 13, but he had a hell of a guardian: his grandfather and bandleader, the north Mississippi hill country blues giant R.L. Burnside. For 11 years, Cedric played drums behind his “Big Daddy” throughout the U.S., Europe, and parts of Asia, helping spread the sound of Marshall and Benton counties.

He’d started when he was barely big enough to climb up on a drum throne, playing house parties and juke joints with R.L. and his neighbor, the region’s other musical patriarch, Junior Kimbrough. (Cedric inherited the drum chair in Kimbrough’s Soul Blues Boys from his father, Calvin Jackson.) And Cedric played with both men until Kimbrough’s heart gave out in 1998 and R.L. was sidelined by a major heart attack in 2002, nearly idling him until his death in 2005.

Cedric’s heart, however, is that of a musical lion. By the time he was in his late teens, he was considered one of the finest blues drummers on the planet—and he has four Blues Music Awards to certify that. Luther Dickinson of the North Mississippi Allstars praises Burnside for “keeping authentic hill country drumming alive while casually modernizing the tradition,” and adds that “as a singer-songwriter he’s writing new blues classics of his own, and he’s become one of the great hill country guitarists.”

Frankly, while Cedric’s contributed drums live or on albums to Widespread Panic, T-Model Ford, the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, Paul Wine Jones, various bands with Burnside and Kimbrough family members, and many others—even Jimmy Buffet, his deepest mark has been made as a leader and co-leader in a series of thunderous, hypnotic, groove-intensive duos.

The guitar-and-drums format is in his bones. It’s a longtime staple of downhome and raw blues, going back to Hound Dog Taylor and beyond, and continuing up through his Big Daddy’s band, T-Model Ford, and Lil Poochie Watson & Hezekiah Early, to Jon Spencer, the White Stripes, and the Black Keys. Since 2007, Cedric has made five albums with duos: two with funky Tele-slinger Lightnin’ Malcolm and three with his guitar-playing cousin, Trenton Ayers. The latter were under the name the Cedric Burnside Project and include Descendants of Hill Country, which was nominated for a Grammy in 2016.

Ayers is a burning guitarist, but fans who’ve attended Cedric Burnside Project shows in recent years have been treated to Cedric’s emergence from behind the kit, as he’s moved up front for a portion of the sets to play a handful of originals and chestnuts on acoustic or electric guitar, nailing the transporting drones and mesmerizing riffs that give unadulterated north Mississippi hill country blues the mojo to leap genres and appeal to rock, blues, psych, and jam fans.

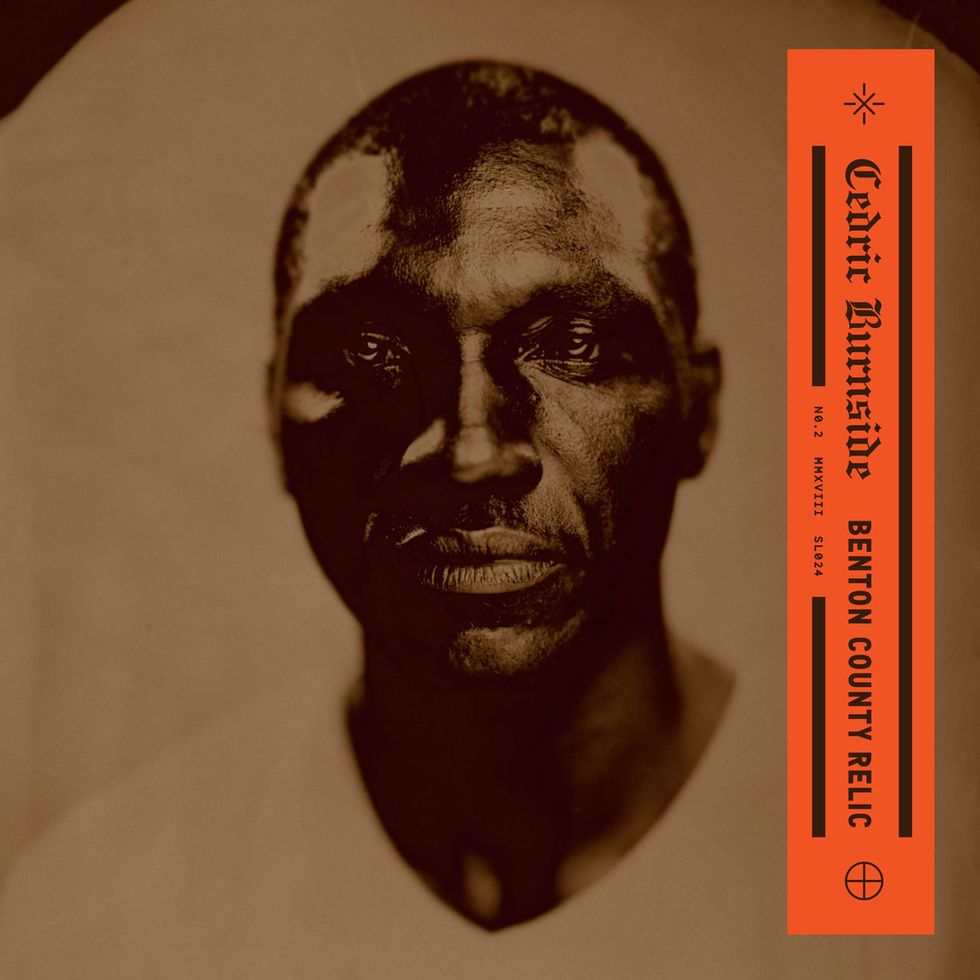

Turns out, Cedric Burnside has been seriously assembling his guitar skills for more than a decade, outside of the spotlight. And on his new album, Benton County Relic, Burnside stays in front of the kit, leaving the drumming to his engineer and partner on the album, Brian J, and delivering a modern hill country guitar manifesto. Cedric’s guitar tones are dirtier than a dog in a muddy Mississippi cotton patch. The stories, like all great blues, are irony-free and honest—and his singing drives them home the way Josh Gibson used to hit balls. The autobiographical “We Made It” is the tale of his rise from poverty in 3:35, set to stuttering, marrow-revealing guitar lines. “Hard to Stay Cool” takes a cue from Kimbrough’s sinuous 6-string melodies and chanted vocal style, but it’s amped by Cedric’s big-thumbed tone and his pure river water voice. It’s timely as hell, in this era of hot heads. And for a double-shot of that good old R.L. Burnside north Mississippi hill country grind, listen to “Death Bell Blues,” which Cedric and Brian J spackle with extra coats of rust.

TIDBIT: The Stratocaster on Burnside’s debut album as a guitarist was recorded, through two amps and a DI line, by drummer, guitarist, and engineer Brian J at his Brooklyn studio.

If you’re tired of typical I-IV-V fare, Cedric just might be your man, and Benton County Relic might be the tonic you’ve been wanting. And if you’re still a little mystified by what this “north Mississippi hill country guitar” stuff is, let Cedric explain.

What’s unique about Mississippi hill country blues guitar?

Hill country blues is very unorthodox. It’s got a very unorthodox style of rhythm. Many people are used to Chicago blues, Texas blues, and even Delta blues, you know, having the eight-bar or I-IV-V on it. With this music, there are no bars, you know? [

Laughs.] They like to hold the notes and bars as long as they want to. I see hill country blues as being more like they gonna do what they wanna do. [Laughs.] It’s definitely got its own thing—its own rhythm and everything.

It’s so straight from Africa that I feel it in my bones, in my soul, you know? I was listening to Ali Farka Touré about three or four years ago, and I was like, “Oh, that’s some old Junior Kimbrough song.” I really thought it was Junior until he started singing, and when he started singing, I was like, “wow.” Hill country is very African sounding.

Let’s talk about your musical background and how you started playing with R.L. Burnside, your Big Daddy.

My Big Daddy used to do house parties every other weekend. And as a young kid, I’m one of several grandkids that used to set there, at 5 or 6 years old, just listening at the music and watching.

Watching my Big Daddy and my dad and uncle play, I just knew in my heart and soul that that’s what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. Nobody had to tell me. My eyes bugged wide open because I loved that music so much. So one evening I just went up to jump on the drums, when my Big Daddy and dad took a break to go drink the moonshine and get refreshed. And people started saying, “Look at that little guy! Man, he’s gonna be good some day.” That turned into me playing the juke joints at age 10, with Big Daddy and Junior. I did my first tour with Big Daddy at age 13, and I’m still going today. I just thank God for everything that R.L. Burnside and Junior taught me. Now, I’m about to be 40 on August 26.

On acoustic or electric guitar, Cedric Burnside’s sound is full of rumbling strings, plucked punctuations, and hypnotic riffs—all part of the code of north Mississippi hill country blues. Photo by Joseph A. Rosen

Touring as a 13-year-old sounds like a hell of a way to see the world.

For that first tour, we went up to Toronto. I had never even been out of Mississippi. I had butterflies, because I was only just used to playing local house parties or the juke joints, you know? And so to get there and see a different crowd, and wondering are they even gonna like this music, and wondering if I’m gonna mess up or not. It was just awful—the butterflies in my stomach. But after the first song, they started clapping and shouting, and I was like, “Oh, okay, cool!” Then I knew I was ready.

What led you to play guitar, and when did you start playing?

I never put a whole lot of interest in it, like I did the last eight or nine years, but I’ve been fiddling around with the guitar for the last 13, 14 years. I just finally took it seriously, mainly because when I write a song I want the music to be right. Before that, I had to sound the chords out with my mouth. People didn’t understand what I was going for. I didn’t even know what key it was in. A lot of times I sounded stupid! [

Laughs.] And so I told myself, man, I just got to learn to play guitar so I can play my music for people, as opposed to trying to hum it out.

Luther Dickinson gave me my first guitar, and I always took that guitar everywhere with me, no matter where I went. I practiced in the hotel room a lot. I practiced in my house on my porch. I kinda developed my own style. Luther showed me a little something on the guitar, when I was on the road with him and JoJo [Hermann] from Widespread Panic several years ago. And I’ve been doing it ever since: Trying to get better and better, and get better and better at songwriting. I have to say, the guitar is my newfound love.

Well, I’ve heard a lot of hill-country guitar, and I don’t think anybody’s doing it better than you right now. What kind of guitar did Luther give you?

It was an old Harmony acoustic. I’ve still got that guitar.

The guitar-and-drums duo format seems to be the basis of most Mississippi hill country style bands. What kind of freedom does it give you? And what kind of responsibility does it impose on you?

That’s just what I know. I’m not opposed to playing with a bass player. It’s just that that’s what I’ve been doing my whole life: the raw hill country blues. Even when I toured with Big Daddy, it was like a duo, with him and Kenny Brown on guitars. But a lot of times at the juke joint [Junior’s Place, which was run by Kimbrough], Kenny wouldn’t be there or the bass wouldn’t show up, so me and Big Daddy would have to do a duo. We’d make it work. So that’s why I decided to keep my band and my albums as a duo.

Guitars

Fender Stratocaster (studio)

Ibanez AR (live)

Fender Squier (live)

Amps

Fender Bassman (studio and live)

Fender Twin (studio)

1x10 Supro or Silvertone (studio)

Effects

Fender Reverb tank (studio)

Electro-Harmonix Memory Man (studio)

Boss EQ (live)

Strings and Picks

Various .011 sets

Brass and glass slides

As a guitar player, I wouldn’t say a duo gives me more freedom, because I have to play the lead and the bass at the same time. That’s a task. You gotta mind your Ps and Qs to do the lead and the bass. It takes some work and a bunch of time to get used to it. It kinda comes second nature to me now that I’m able to write my songs in the style that I want to play my music in. And the sound of the guitar is important. I like to think of it as dirty. [Laughs.]

Let’s talk about Benton County Relic. On past albums, you’ve primarily sung while playing the drum kit. This time your guitar is out front all the way. Why make your debut as a guitarist-frontman now?

I write songs all the time, and I wanted people to finally hear my songs the way I intend them, instead of another guitar player interpreting. I want people to know who I am and what I go through in life, and what my family and friends go through in life, and, hopefully, when the people hear it, they can relate. For me, this was overdue.

What gear did you use in the studio?

I was using a Fender Twin, a Fender Bassman, and a Stratocaster my friend Brian J had in the studio.

The guitar sound is fat and filthy. Did you use any overdrive or distortion pedals?

To be honest with you, I’m not really used to pedals. I use just a little equalizer pedal to give me a little boost. But that’s about it. Brian J put one on “Call on Me.” I forget the name of the pedal that he used to make it kinda, I guess, Caribbean-sounding. [

Laughs.] [For more details see the sidebar, “Capturing the Hill Country Guitar Sound.”]

But I do crank the Bassman up. I kind of put the highs and the lows at the same level, but try to put the volume on about 6 or 7, to bring out that good bottom.

We did the whole album in two days, just going song after song after song. We didn’t even listen to rough mixes because we didn’t have time. And the night before I left the studio in Brooklyn, we listened at all the music, and we was like, wow, we couldn’t believe what we had come up with.

With his Ibanez—or any other electric guitar—strapped on, Burnside handily dials in a raw, rough-and-tumble sound that falls somewhere between Muddy Waters and Neil Young’s “Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black).” Photo by Sammy Slate Productions

What guitar do you take on the road?

I’ve got an Ibanez and a Fender Squier.

What slide do you use?

A very thin brass slide, and sometimes I use a glass slide. I just purchased another thicker glass slide, but I haven’t used that as much. And I just play with my fingers.I tried to use a pick, but I just can’t get it. It don’t feel right to me. It didn’t feel natural.

R.L. played in open G and standard. What tunings do you use?

I played most of the songs on the album in standard tuning. And about three or four was in open tuning—open G [D–G–D–G–B–D].

Let’s get back to your songwriting. For someone working in a musical style that’s as close to pure African music as blues gets, you like to keep your lyrics very personal, real, and to-the-moment. But you also balance that with what seems like a responsibility to carry on your family’s musical legacy and the legacy of the Mississippi hill country sound.

Well, I like to be true to who I am, you know, and I like to write my music according to how I live my life. It don’t matter if I break up with a woman or if I got mad at a family member or if my car quits on the side of the road in the hot heat. Whatever happens in my life, or in my family’s life, or to my friends, I like to write about that. There’s a lot of people out there writing songs about things that they don’t do. And they write songs about things they don’t have. But that’s not me. I just really hope that people can relate to it.

I got a song on my Benton County Relic album called “Hard to Stay Cool.” I honestly think that when people hear that song, they’re gonna feel it and they’re gonna know what I’m talking about, because I would say that everybody in the world has been in a situation where it was impossible to stay cool, you know. And maybe now more than ever.

I think these days here, anybody can have the blues. The blues came from black people and their culture—from slavery, from being stolen from their own homes to work for people they didn’t even know, and get beaten by people they didn’t even know. And to be able to evolve from that, and out of that, and being able to talk about it through their music—that’s where the blues comes from. And things that seemed gone long ago are happening again.

But you know, I don’t necessarily feel like I have a responsibility to carry on this style. It’s what I want, it’s what I love, and it’s who I am. I know that there’s other hill country blues artists out there, but I feel like I am hill country blues. And to try to fill Big Daddy’s shoes? No, I’m not trying to fill his shoes. To try to fill Junior’s shoes? No, I’m not trying to do that. I think that’s impossible, actually. But I do think that we should keep it going, because this is what they left for us. This is what they instilled in us. And this is what the people want. And R.L. or Junior is not here to still give it to them, so I think they would want me to do it, you know? That’s what I’m gonna do for the rest of my life, man.

Total fanboy question: You and Kenny Brown were the band in the juke joint scenes with Samuel Jackson, and on the soundtrack, for the 2006 movie Black Snake Moan, which had a dedication to R.L. Burnside in its credits. What was that like?

It was actually really great, you know, getting to hang out with Samuel L. Jackson, Christina Ricci, and the cast. We stayed about four or five months, hanging out with Samuel and teaching him some of the songs, because he did not know any of the songs. He wanted to know how to sing these raw blues songs. He’s really a great actor. It was amazing watching him learn from us and go and do it in a scene. Most of it was filmed in Mississippi, but the juke joint scenes were filmed in Memphis, Tennessee, at Ernestine & Hazel’s.

So, Sam Jackson doesn’t play guitar, does he?

He didn’t. I mean, he might play now, because I hear he’s into the music pretty strong now.

How many dates a year do you play, roughly?

Well, this year has been slower, but normally I’m booked anywhere from 250 to 300 gigs a year.

Man, you’re working your ass off

You got that right! [

Laughs.] I kinda had to slow it down a little just because it was too much. It’s bound to be the same after the CD comes out, but I’m looking forward to that.

Being away so much must be rough on your family.

Oh yes, definitely. I got three daughters. My oldest is going off to start college, and I got a 15-year-old, and my youngest daughter just turned 13. I miss them a lot when I’m out on the road, but I’m glad they know daddy does this for them—as well as for myself. I

love this music, and I love the fans that love this music, but you know, I also do it for my babies.

One last thing: What do you think is the most important thing you learned from all those years playing with your granddad?

I would have to say that the most important lesson he taught me is to treat people how you want to be treated. And I’m not gonna say I have treated people the way I wanted to be treated my whole life, but I tend to do it a whole lot more the last eight or nine years. I try to honor what my Big Daddy taught me.

YouTube It

Listen to Cedric Burnside perform an acoustic version of “Poor Black Mattie,” which was a core part of his grandfather’s repertoire. Note the use of repetition and droning, with small melodic variations in his picking technique. That’s why north Mississippi music is often labeled “trance blues.”

Cedric at work behind the kit with his Cedric Burnside project, which includes his cousin, Trenton Ayers, on guitar. In recent years, their shows have included a solo segment with Burnside playing guitar and singing—a live preview of Benton Country Relic. Photo by Bill Steber

Capturing the Hill Country Guitar Sound

The term “rusty tractor blues” is a favorite tag applied to the music from north Mississippi hill country, implying a sound crusted with age, yet gifted with rugged beauty. Cedric Burnside’s guitar tone on Benton County Relic is a perfect example. Amps fart and roar under the attack of his fingers. They grind, but with a lubrication of sweet honey that makes the friction settle warmly in the cerebrum. And Burnside sings in a rich, fluid baritone that floats over the instruments’ exalted oxidation.Burnside’s guitar sound on his new album will ring familiar to fans of his “Big Daddy,” R.L. Burnside, but it also ricochets deeper into the gutter and into the celestial, thanks to the portly, rumbling overtones and gossamer of reverb and delay applied by Brian J, who recorded the album at his Brooklyn studio.

J, who also plays drums on the album and leads the bands Pimps of Joytime and Gitkin, was already a fan of R.L. Burnside and north Mississippi music when he and Cedric were both hired for a gig with New Orleans-based singer-guitarist Papa Mali.

“We were getting to know each other at the rehearsal, and at one point Cedric played something on the guitar that immediately got me excited, so I thought ‘I better jump on the drums,’” says J. “Within minutes, I knew we had something special.” The feeling was mutual, and later they both convened at J’s Brooklyn studio to make Benton County Relic and a second album, already in the can, in just a few days.

Benton Country Relic’s spectacularly dirty core guitar sounds were achieved organically. J ran Burnside, who mostly played J’s Stratocaster, into two amps: a tweed Fender Twin and a 1x10 Supro or Silvertone, with a third line going DI. “I reamped that DI guitar and really messed around with it on the board, and I unplugged one of the speakers in the Twin to get a little overdrive.” No overdrive or distortion pedals were employed. The special sauce was provided by a reissue Fender reverb tank and an Electro-Harmonix Memory Man. J also used some ambient mics to pick up muffled tones from the blanketed amps and room bleed between the drums and amps, lending the album’s sound a juke-thentic edge.

But the core tone, says J, “is in Cedric’s fingers. He doesn’t use a pick. He hits the strings hard and plucks them so they ring with a lot of vibrations. And while he’s 100-percent authentic to the music he grew up on, he’s an artist on his own terms. He’s of now.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)