“I love digression,” Elliott Sharp says matter-of-factly, as he sips a piping hot cup of espresso. It’s drawn from a vintage machine in his charmingly bohemian East Village recording studio—which also happens to be home to his Zoar record label, launched back in 1977. We’re sitting in a large room opposite a wall of exposed brick, surrounded by guitars, amplifiers, and a plethora of exotic stringed instruments, all of them painstakingly assembled or acquired over years of sleuthing, searching, and experimenting. The space feels more like a lab or a workshop than a proper studio—a vivid reflection of Sharp’s legendary and inexhaustible curiosity.

“When it comes to creative digression,” he continues, “as an improviser, you have to be able to keep the entire narrative arc somewhere in the background, while at the same time feel free to explore all the places that it sends you. When I’m composing, like if I’m writing an orchestra piece or a string quartet, I want it to have that structural integrity over the entire course of it, but at the same time, I want to feel as if anything could happen—that it’s, in essence, improvisational at any given moment in the music itself.”

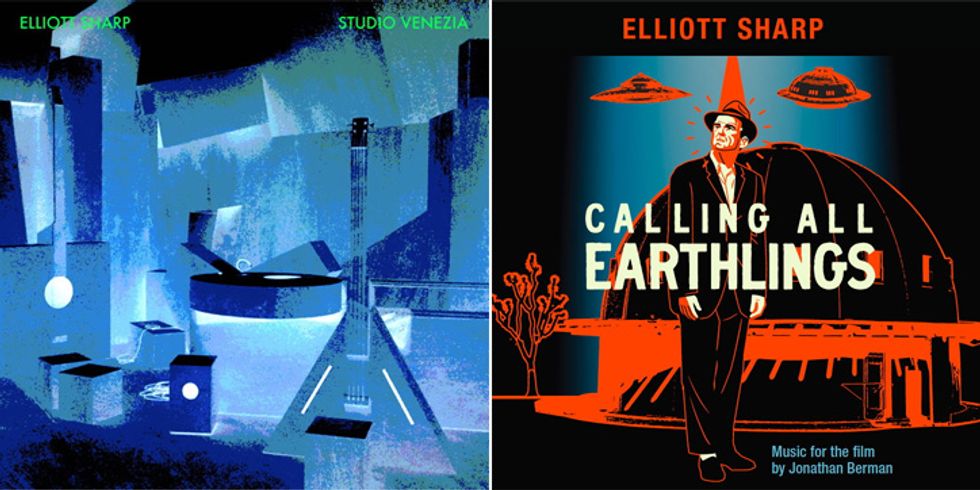

There are multiple points of entry into the music of E# (as he’s known to his fans), but it helps to start with a handful of his most recent projects. Studio Venezia, recordings both solo and with drummer Mark Sanders in a studio custom-designed by artist Xavier Veilhan for the 2017 Venice Biennale, is a purely improvisational excursion, played on-the-spot and, for some performances, using unfamiliar instruments like harpsichord, the tuba-like serpent, and a throwback EMS Synthi AKS synthesizer.

“That was like going into a playground,” Sharp says with a laugh. “Xavier had Radiohead’s live recording setup as the basic studio, with this beautiful old API desk and a lot of outboard gear—even some of the same stuff I have, so I really felt at home.” And, of course, there were numerous stringed instruments, including a 16th-century vihuela and a Spanish baroque guitar, which features prominently on the album’s haunting closer, “Pareidolia,” with Sharp bending, tapping, and plucking the strings in repetitive patterns that recall Moroccan trance music. “To keep the improvisational nature, I just picked it up. I didn’t tune it. I think a lot of the different tonal stuff comes from the fact that the strings weren’t in tune.”

By contrast, Sharp’s score for the Jonathan Berman documentary Calling All Earthlings is a bit more traditional, relying on various electric and acoustic guitars, synthesizers, and drum machines to deliver specific moods and melodies. “Dry Gulch,” for example, channels Hawaiian slack-key sounds and a taste of Ry Cooder’s early slide guitar work for the films of Walter Hill, while “Horrors of La” is a haunting two-minute surf anthem worthy of Dick Dale himself.

“That had been in the works probably for about five years,” Sharp recalls. “I’d scored Jonathan’s previous film, Commune, so we have a method. He’d give me very basic guidelines, or keywords, or a feeling. He might reference a band, you know, ‘Make it sound like the Grateful Dead,’ or if the Dead were playing techno or something. And then I would just go. He also gave me a lot of hot buttons that I really resonate with, like psychedelia and North African trance music, so I was trying to get that feel, but in a two-minute track. A few things with tenor guitar or steel guitar were really hitting that pretty closely.”

Then there’s 4am Always, the most recent recording by Sharp’s longtime avant-blues ensemble Terraplane, with bassist David Hofstra, drummer Don McKenzie, and singer Tracie Morris. Released in 2014, the album adds another chapter to the long narrative arc of the core trio, which began back in 1994 (then with drummer Joe Trump) as an outlet for Sharp to dig deep into the music of his blues heroes. Eventually, one of those heroes, Chicago blues stalwart Hubert Sumlin, joined the fold for a string of monumental sessions, including the essential slab Blues for Next (released in 2000) and the ultra-modern Secret Life (2005), and subsequent European tours.

“I almost can’t tell you what it was like, after all these years of listening to Hubert, to finally meet him and then to play with him,” Sharp says. “I mean, so much of what he did defined what modern blues-rock would become. He really wrote the book. When I first heard Howlin’ Wolf—and I got turned on to him through the English blues guys and Paul Butterfield—I’d go into the city and wander around Sam Goody’s record store, and it was the Wolf record on Chess called The Real Folk Blues that hit me first. Then I heard this insane guitar, especially on “Goin’ Down Slow” [from Wolf’s Rocking Chair album], and eventually I found out who [Hubert] was.”

Sharp’s most recent releases cover some of his many facets. Studio Venezia is a solo improvisational outing and his soundtrack for Jonathan Berman’s documentary, Calling All Earthlings, ranges from synth textures to Hawaiian slack-key guitar to surf.

Although Sumlin died in 2011, Sharp still speaks of him as though he might walk in the door at any moment. “He’s been over here a bunch of times—he loves drinking coffee, by the way—and, even watching him play, I can’t tell what he’s doing. Hubert had such a vocal sound because he played with his fingers on his right hand. His left hand was pretty conventional, but I’ve watched his right hand up close. He had an incredibly relaxed right hand. If you ever watch a kora player, it’s the same thing. I saw Alhaji Bai Konté a couple of times, and he was just so relaxed, and yet the incredible clarity of the notes—like Lenny Breau,also.”

Sharp has more in the works with Terraplane, as well as numerous other projects on the burner. (One recent collaboration, Err Guitar, with fellow guitar explorers Mary Halvorson and Marc Ribot, seems destined for a follow-up.) And then there’s his just-released memoir IrRational Music. Part tour diary, part manifesto, the book details everything from his brief encounter with Jimi Hendrix (at the famed, and now defunct, Manny’s Music in New York) to his guiding principle for composition: that the Inner Ear is where all music begins. The next step, as Sharp explains it, resides in how you bring that sound into the world. The way we act on this creative impulse, with instruments and processes and learning curves, is an ever-changing feedback loop that we have to constantly strive to break down and refine.

At least, that’s how a lifelong improviser might see it.

Sharp’s RE 8-string was built by master luthier Saul Koll. Also among Sharp’s collection are instruments he built himself that range from slabs with bass and guitar necks to a parts T-style thinline. Photo by Bill Murphy

Is there a secret to cultivating an improvisational spirit?

Well, you have to listen. You have to be open and be in the moment. At the same time, it’s a fine line between having a personal identity and repeating yourself, you know? You develop a style, which means that when one thing happens, then you’re likely to do that, so the question is how do you defeat it? I mean, so much of what we do is defined by muscle memory. People think memory is in the brain, but it’s distributed over our entire being. And it doesn’t just end with our muscles. A band that plays together has a collective memory that exists outside their own physical bodies. It could be pheromonal—like a cloud that hangs over a band when they play together—but it fits with this notion that the memory exists completely outside of the individual states of the players.

Well, how do you get yourself beyond that—beyond the repeating? Do you have a ritual?

I don’t. I drink more coffee [laughs]. A bunch of us always used to joke that the perfect improviser would have absolutely no short-term memory—so as I go into my golden years, I hope to achieve that! But it’s just about trying to be critical. On the one hand, you do things that work. You can say “Well, this situation, this groove, I’ve been here before and I know that I like this sound, so I’m gonna do it,” because it works and it feels good. And at the same time, you go, “Well, how can I find some way out of it?”

You’ve also managed to strip touring down to a science. What do you travel with these days?

I don’t like carrying a lot of equipment around, because I’m touring mostly in Europe by train and plane, so I have a few travel guitars—either my Koll 8-string, or my Strandberg 8-string that Ola [Strandberg] gave me. I used that on the sessions for Studio Venezia with Mark Sanders. John Edwards overdubbed bass on the duo tracks, and that will be released as a trio album called The Clinamen for our European tour this fall. The Strandberg is very lightweight and really kind of a shredder guitar, with a nice wide fingerboard, and I’ll play that mostly with objects. Then I have an Aria Sinsonido, which is really remarkable. I just wanted something cheap and disposable to carry with me, and it ended up being a great guitar. It’s a pretty unique knockoff that was licensed from Soloette in Eugene, Oregon. His pickups are really fantastic.

My main guitar for doing improvisational stuff has a Godin classical neck on it. I had the body in my junk box for, like, 30 years. Same with the pickup. I think it’s a Lafayette, DeArmond-style, and then it has a Peavey Super Ferrite pickup, which is like a poor man’s Charlie Christian. They’re really great. The neck is very wide, with an ebony fingerboard. I like the definition that an ebony fingerboard gives to the notes you play. The bridge is cut from an aluminum tube from my mother’s garden [laughs]. It actually has a filtering effect, almost like a cocked wah. I hand-shape them, and I think the hollowness gives a bandpass filter character to the sound. I’ve put those in a few guitars.

Guitars and Basses

1964 Fender Stratocaster

1973 Fender XII

1987 Fender D’Aquisto Elite

1987 Fender American Vintage reissue ’57 Stratocaster

1956 Gibson ES-225TD with Bigsby tremolo

1967 Gibson Les Paul Custom

Hagstrom Viking XII

1996 Henderson Greco 8-string guitarbass custom built by Doug Henderson with a neck by Carlo Greco

Koll RE 8-string custom designed by Saul Koll

2015 Strandberg Boden 8-string designed by Ola Strandberg

T-style thinline with a Charlie C pickup

Norma (built from junk-box parts including a Norma/Eko/Vox body and Godin classical neck, with a Peavey Super Ferrite and an alnico single-coil pickup of unknown origin)

Universe (lightweight Chinese paulownia body with SX neck, Teisco tremolo, Kydex pickguard, and pickups—two black-foil and one gold-foil—salvaged from Teiscos)

FireStrat (Chinese thinline poplar S-style body, Mighty Mite neck, and three Artec Firebird pickups with ceramic magnets)

1956 Gibson CF-100

1946 Martin 00-18

Godin Multiac Duet (modified)

Aria Sinsonido

1973 Fender Bass VI

1966 Hagström H8

1966 Hagström Viking

Amps

1964 Fender Princeton Reverb

Fender Deluxe Reverb

Fender tweed Champ modified by Matt Wells

Fender 75 modified by Matt Wells

1974 Fender Bronco

Effects

Boomerang III Phrase Sampler

DigiTech Whammy II

Electro-Harmonix Double Muff Nano

Electro-Harmonix MicroSynth

Eventide PitchFactor

Hotone Komp compressor

Hotone Blues overdrive

Moogerfooger MF-102 Ring Modulator

Moogerfooger MF-101 Lowpass Filter

Strings

Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.010–.046) on Stratocasters and Telecasters

D’Addario (various gauges) for other guitars

What about some of the other guitars you have here? I’ve seen you play Strats and Teles before.

I have a few, but I also like to prowl Craigslist and get junk that someone else would be throwing out. For example, I like the idea of the Fender Jaguar more than I’ve ever really liked the Jaguar, so I found this one Teisco on Craigslist and installed three Jaguar pickups. And, of course, I painted it copper, because copper paint will sound better [laughs]. I found an online forum with a big discussion about that. Billy Corgan made some comment about how the color of the guitar absolutely affects the tone. I think that’s a little bit taking the piss out of things, but at the same time, I do think you play differently. If a guitar looks a certain way, you’re going to play a certain way.

So anyway, with the pickups and flatwound strings, I have this gnarly-sounding guitar. It has a vibe, it’s not so heavy, and it sounds really nasty. Plus I think it covers my surf needs—not that I get a lot of calls for surf music, but I tried to capture some of that on Calling All Earthlings, on the first track (“Gila Monster”). Jonathan wanted something that was twangy and surfy, but Western. I think I played the melody with a Tele—it was Teles and Strats.

And you travel with effects, too, right?

My favorites now, when I’m touring, are the little Hotone pedals, because they’re small and they sound good. I have a compressor and an overdrive, so I can get either a clean overdrive, if I want, or something a little grittier like a Tube Screamer sound. Then I have a [Electro-Harmonix] Double Muff Nano pedal, and that gives me some thick, greasy fuzz. Then the PitchFactor from Eventide—I’ve been using that since it came out, with an expression pedal and all my own patches—and the Boomerang sampler, the small one, which allows you to have four loops and do reverse effects.

With the PitchFactor, I’m always changing my patches, and I try not to memorize what I have, because I really like to have that unknown factor coming in. I’ve saved a couple of them, but I’m always tweaking them so that when I play a gig, it’ll throw me for a loop. It’s going to excite me into some place new and wonderful—or make me hit the switch to the next patch. I’ve had that happen, too.

How about your amplifiers? You have quite a few Fenders here.

I love the blackface Fender Deluxe Reverb for small venues. But I can almost get a sound out of anything, because I think you’re in a feedback loop between fingers and ears—although I usually put “no Roland JC-120” on my rider [laughs]. It’s just too clinical, you know? I did find once, because I was forced to use one, that if you click the distortion switch on but don’t turn it up, you get a sound that almost has a little warmth to it. So if I have to, I will use a Roland.

But anyway, I really prefer the Fenders, and for recording, the little Fenders. I have a tweed Champ that Matt Wells [in New York] reworked for me, along with a Fender 75 that he rebuilt with a Marshall transformer. I like to record with amps, but I record direct a lot, too. I’ve done things with plug-ins and nefariously tested them with friends and told them, “How do you think the ribbon mic sounds?” You know, if you have the sound in your ear, I think you can pretty much get to it. Although when you’re playing in a room, there’s nothing like an amp. I think you can get a dynamic range, and again, that feedback loop between fingers and ears is much better if you’re playing through an amp.

Why do the blues resonate so powerfully with you as a musical influence?

Well, it’s about vocalizing. It’s not about licks. It’s about having the guitar be an extension of your voice, or it becomes the voice. It’s almost as if your whole essence goes into the instrument and has to come out through the amplifier. To bend the strings—it doesn’t matter. Of course we all like to be thrilled by fast guitar playing, but it’s only necessary when the music requires it, you know? I hate guitar athletics. For the blues, just to be able to play one note and make it sing is really, to me, one of the great things.

Do you think it’s harder now to maintain a career as an experimental musician and composer?

Well, it’s never been easy. I mean, the law of inverse proportions always states that the less artistic value or soul value something has, the more commercial value it has [laughs]. So sometimes it’s hard to stay optimistic—especially in these times. My kids are teenagers now and I tell them, “You guys are a lot smarter than we are, so it’s on you. You’re gonna figure this out.” And I do think music has a lot of possibility to change people’s chemistry. I mean, that’s really why I do music. It’s about psycho-acoustic chemical change. That idea of affecting how people think and how they see the world, and it affects how you see the world as you play music, when you get in touch with that continuity. All of a sudden, the world becomes more clear and more possible. You get a little taste of the infinite, you know?

Elliott Sharp takes it outside, literally, for Plaza Guitarz, a day of music he curated at La Plaza Cultural in New York City in 2017. EBow, springs, tapping, extreme bends, and slide are all among the elements of his technique on display.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)