According to Paul Bender—bassist for the trippy yet eminently soulful Melbourne-based quartet, Hiatus Kaiyote—the band's live sets often meld into one continuous song. "I never really get a break in the set because we always play all our tunes together for some reason," he says. "I basically never stop playing. I don't have a moment where I am not doing something at any point in the set."

This all-in, throwdown approach is intrinsic to understanding what Hiatus Kaiyote is about. They'll follow an idea, no matter how obscure or complex, wherever it leads, which creates a through-composed structure that gives their music an otherworldly feel. They do have more conventional verse/chorus-type songs as well—"Chivalry Is Not Dead," and "Red Room" off their latest release, Mood Valiant, for example—but even there, the music oozes a loose, what-are-these-amazing-sounds-I'm-hearing energy.

Hiatus Kaiyote - 'Red Room' (Official Video)

Hiatus Kaiyote formed in 2011 and earned Grammy nominations in the R&B category for each of their first two releases before going on what was supposed to be a short hiatus in 2017. But that break seemed to extend indefinitely. During that time, lead singer and guitarist Nai Palm (born Naomi Saalfield) had a terrifying brush with breast cancer (now in remission). Then, with Mood Valiant almost completed, COVID hit and put everything on hold. Although for them, the silver lining was that they were able to isolate together. "We were wrapping it up when that shit went down," Bender says about the final sessions for the album. "We went into the bunker together. It kicked our ass into finishing the record, because there was nothing else to do."

"The biggest part of my attraction to guitars I like is the playability. If it feels good to play, I'm more likely to be motivated to write on it." —Nai Palm

Mood Valiant is the quartet's third full-length and continues their seemingly effortless fusion of jazz-like harmonies, electronic textures and patches, and subtle-yet-funky grooves. Added to the mix are lush string and horn arrangements from Brazilian composer Arthur Verocai (more about him in a minute), and an adventurousness that seems almost prog, as heard on songs such as the whirling and unpredictable "Rose Water," the beautiful piano ballad "Stone or Lavender," and the aforementioned experimental-yet-grounded "Chivalry Is Not Dead."

Bender is a driving force behind the band's groove. He's officially the bassist, but in addition to holding down the low end, he also covers upper-register chordal work—timbres and tones you'd expect from a guitar—as well as more ambient and spacious synth-like textures. He's not the band's only multitasker. Drummer Perrin Moss plays on a mutant kit that resembles a cross between a standard jazz-type setup with a large assortment of acoustic noisemakers, electronics, and keys. Keyboardist Simon Mavin lives in a space that combines vintage gear, samples, and modern pads, and Palm is guitarist and lead singer, although she'll often put the instrument down to focus on her complex and harmonically rich vocals.

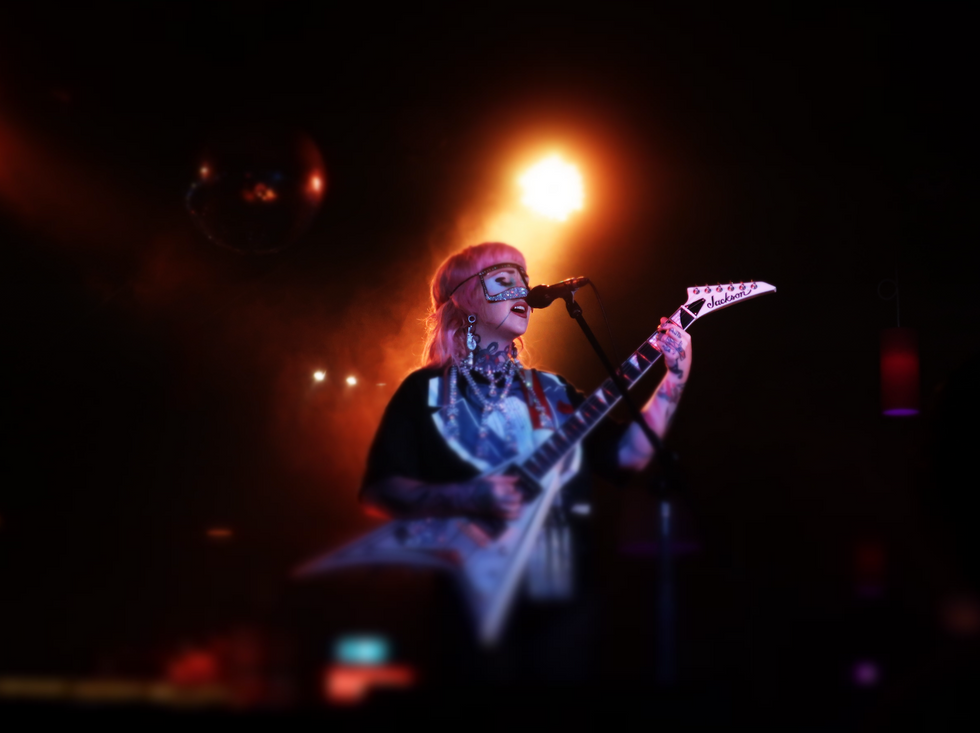

Nai Palm subverts expectations—and makes a big style statement—by playing "gentle shit" on her Jackson Randy Rhoads V RRT3 Pro Series.

Photo by Stephan De Witt

"When I write songs alone from scratch, it's usually on a guitar," she says. "A big part of the motivation to play or not play depends on how the song feels emotionally, performance-wise. Guitar is super cerebral and focused, which I adore and I find a lot of freedom in, but it can be limiting singing because your brain is essentially doing two separate tasks. It's fun to keep my options open and not just be stuck to one thing."

Given the band's multidimensional spirit, it's no surprise that Bender has deep roots in various disciplines. His earliest experiences as a youngster were playing metal and grunge, but at one point he was halfway around the world, studying jazz at the University of Miami and cutting his teeth on upright bass.

Paul Bender's Gear

Bender's behemoth of a pedalboard.

Bass

- Ernie Ball Music Man Bongo 6

Amps

- Ampeg SVT heads and cabs

- Vintage Coronets

Strings

- Ernie Ball Slinky Long Scale 6-String Nickel Wound Electric Bass Strings (.032–.130)

Pedals

- 3Leaf Audio Octabvre

- 3Leaf Audio Wonderlove Envelope Filter

- 3Leaf Audio You're Doom Dynamic Harmonic Device

- Chunk Systems Brown Dog Gated Bass Fuzz

- DigiTech X-Series Synth Wah Envelope Filter

- DigiTech Whammy

- Ernie Ball VP JR Volume/Expression Pedal

- Mooer Lofi Machine

- Mooer Yellow Comp

- MXR Bass Octave Deluxe

- MXR Carbon Copy Analog Delay

- MXR M109S Six Band EQ

- MXR Talk Box

- Roland RE-201 Space Echo

- TC Electronic PolyTune

- ZVex Box of Rock

"I don't really play the upright that much anymore," he says. "But there was a good period of time when that was my whole bag. I was really into playing upright—walking bass, changes, standards, all that stuff. I definitely went down that rabbit hole pretty hard. It's pretty unforgiving when you step away for a while. It is a distinct physical challenge, and there's a particular double bass fitness that you've got to maintain. You can't really put it down for a couple years and then expect to be any good at it again."

He stopped playing jazz around the time he joined Hiatus Kaiyote, although that's only broadened his horizons, as the band's music draws from so many disparate sources. The challenge, however, isn't just weaving those different pieces together. It's also pragmatic: reproducing their multilayered arrangements in a live setting as a four-piece.

"There is something lovely and distinct about the bass having a chordal function." —Paul Bender

"Simon's only got so many fingers that he can use to play different sounds," Bender says about recreating keyboard parts on bass. "Sometimes I'll try to cover a certain countermelody idea or a chordal idea on the bass, as well as provide the bass function. That can definitely inform the parts that I write. Sometimes it happens in the reverse, where we produce a track where I might have played a regular bass part, but then there will be a bunch of overdubs and a bunch of different things happening, and it's got to be filled out a little bit more. That might change how I approach the bass part in a live context. There are times where I like doing a regular kind of bassline, but I also love getting into the chordal thing, especially when you get into 6-string territory. There is something lovely and distinct about the bass having a chordal function. It can be a really awesome flavor."

But sometimes, the challenge is in the basslines themselves, like when the recorded version is a studio creation of multiple parts stitched together.

TIDBIT: The band flew to Brazil to record composer Arthur Verocai's string and horn arrangements for the songs "Get Sun" and "Stone or Lavender."

"I've definitely done stuff where I've done weird hybrid things," he says. "I'll make a bassline that is comprised of multiple basses making up the whole thing, which is fairly elaborate and stupid, but such a fun approach. I did that on the first record, Tawk Tomahawk, on that track 'Mobius Streak.' I had a Gretsch Electromatic on 'Chivalry Is Not Dead,' from the new record, in the verses, and a Kiesel fanned-fret, super-modern bass, because it has that super-aggressive top-end-y modern thing for the slap bass shit. On the recording, I do a lot more honing in on specific things. That's the time to pull out the very specific colors and accents that different basses give me."

But Bender's only interested in using a varied assortment of instruments when he's in the studio. Once he hits the highway, he's a minimalist and relies on one axe: a blue Ernie Ball Music Man Bongo 6. "I am not taking eight basses on the road," he says. "I am taking one, because … come on. We're not at that level of touring yet where I've got some guy at the side of the stage waiting to run out to hand me another bass for this song. I am not in Radiohead, which would be fun, but that's the pragmatic reality of it."

"I'll make a bassline that is comprised of multiple basses making up the whole thing, which is fairly elaborate and stupid, but such a fun approach." —Paul Bender

"It was partially due to [singer/songwriter and guitarist] Lianne La Havas, who called me on her birthday, drunk from Costa Rica, while I was looking for a guitar," Palm laughs, explaining how she ended up with her white Jackson V. "I went into the heavy metal guitar section to get some space to hear her, and after the call thought, 'Fuck, I'm going to try the spiky Randy Rhoads guitar.' A big part of the attraction was its playability. The action was great and I loved that you can get both a clean and gritty sound from it. I have super-little hands, and the D'Angelico—although it was a vibe—was super heavy. The biggest part of my attraction to guitars I like is the playability. If it feels good to play, I'm more likely to be motivated to write on it. I also love the juxtaposition of playing gentle shit on it. It pisses off the purist metal heads, but I like to think outside of the box." Palm prefers to pair her pointy Jackson with a Fender Twin Reverb.

When Palm plays guitar, she also only uses one instrument. For most of the last decade, that was a custom semi-hollow D'Angelico EX-SS, although a few years ago she made a radical switch, which, for the music she plays, is seemingly incongruous.

Paul Bender loves to experiment with basses and amps in the studio, but when it comes to playing live, he keeps it simple and relies upon his Ernie Ball Music Man Bongo 6, which he prefers to play through an Ampeg SVT.

Photo by Luke Kellett

For Bender, using different basses and layering parts is just one part of his unique approach to the studio. He also has a fun time with amps. On the road, he's content to rent an SVT—or comparable refrigerator-like unit—but in the studio, his mission is clarity and definition.

"If I've got to pick one amp to run the bass through, I am not going to go for a big amp," he says. "I have been getting into these little Coronet amps. They are quite small, and I am not going to blast the bottom end through it." The point is using the smaller amps—in this case, solid-state models from the '60s and '70s—to focus on details and relying on the direct line for the sub frequencies. "The interesting part of the sound, or the flavor, is more that midrange and presence you get pushing it through a smaller amp like a Coronet. I am trying to hear the distinct detail in what I am playing, and the fingers and the touch and the presence. Smaller amps are great when recording. It's a whole different realm. When I am doing a gig, I might be standing in front of the fridge, but in the studio, sometimes the smaller the amp, the better. It condenses the most interesting parts of the sound to that one little speaker."

Nai Palm's Gear

Photo by Luke Kellett

Guitar

- Jackson Randy Rhoads V RRT3 Pro Series

Amp

- Fender Twin Reverb

Strings

- Ernie Ball Super Slinky (.009–.042)

- Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.010–.046)

Pedals

- Electro-Harmonix POG2

- Kink Guitar Pedals Straya Drive

- Mooer Yellow Comp

- MXR Echoplex Delay

- MXR Reverb

- MXR Sub Octave Bass Fuzz

- MXR Uni-Vibe

- TC Electronic PolyTune 3

Hiatus Kaiyote don't have many peers when it comes to their aesthetic and overall approach, although they did find a simpatico creative partner in legendary Brazilian composer and arranger Arthur Verocai, who contributed horn and string arrangements for "Get Sun" and "Stone or Lavender" on Mood Valiant. "We're kind of musical loners," Palm says. "If we work with someone creatively, they have to be able to contribute something uniquely themselves. He was the cherry on top of our album, and it really made the record sing."

To work with Verocai, the band flew to Brazil, played a few shows to cover costs, and met up with him. As it was, showing up in the studio in Rio was not only the first time they met, but the first time they heard his arrangements. It was a risk, but they weren't disappointed.

"If we work with someone creatively, they have to be able to contribute something uniquely themselves." —Nai Palm

"He had a really awesome energy," Bender says. "We got to know him during the session and got to see him at work conducting and rehearsing and recording the ensemble. It was great. We had no idea what he was going to write at all. We thought, 'Hopefully it is going to be cool and we're all going to love it, because otherwise it is going to be fucking awkward if we don't.' But he nailed."

There is a limit to how far Hiatus Kaiyote are willing to push the envelope. Sure, they'll obsess over tones, allow their songs to take them on intricate musical journeys, partner sight-unseen with Brazilian composers, and fly across oceans to collaborate. But they're still an Australian-based band, and there's only so much stuff they're willing to take on the road.

"Fuck flying from Australia with a bass amp," Bender says. "That's a horrible idea. Although if we were Iron Maiden and we had our own plane, that would be a whole different jam."

Hiatus Kaiyote: Tiny Desk (Home) Concert

Hiatus Kaiyote enlist an eclectic—and, in some cases, furry—crew of friends and collaborators for this colorful Tiny Desk (Home) Concert, featuring music from Mood Valiant.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.