There’s no lack of instrumental, improv-based guitar music being made these days, but few bands in that niche exude the muscular power, cosmic intrigue, and impressive blues-rock bite of San Diego-based power trio Earthless. The band’s records undulate through melodies and hypnotic grooves that are fresh yet familiar, and breathe new life into many of the rock guitar tropes that have inspired so many players to fall in love with the instrument.

Since forming in the early 2000s, Earthless’ psychedelic-tinged explorations have channeled the energy and fire that made the first wave of English blues-rock such potent stuff, with the same captivating vitality as Cream, Hendrix, and Peter Green-era Fleetwood Mac. At the core of the band’s sound is Isaiah Mitchell, a full-fledged guitar hero whose undeniable chops and creativity are matched only by his penchant for conjuring the kinds of killer tones many of us have spent small fortunes chasing. Bolstered by groove guru Mike Eginton on bass and powerhouse drummer Mario Rubalcaba (Rocket from the Crypt, OFF!, Hot Snakes), Earthless is the ideal vehicle for Mitchell’s unfiltered, incendiary playing. Outside of the band, his work includes the coveted lead guitar slot in the Black Crowes—a gig he landed during the group’s unexpected 2019 revival and perhaps the ultimate testament to his ascending status as one of today’s absolute finest blues-rock players.

Earthless from left: bassist Mike Eginton, drummer Mario Rubalcaba, and guitarist Isaiah Mitchell.

Photo by Marta Estellés Martín

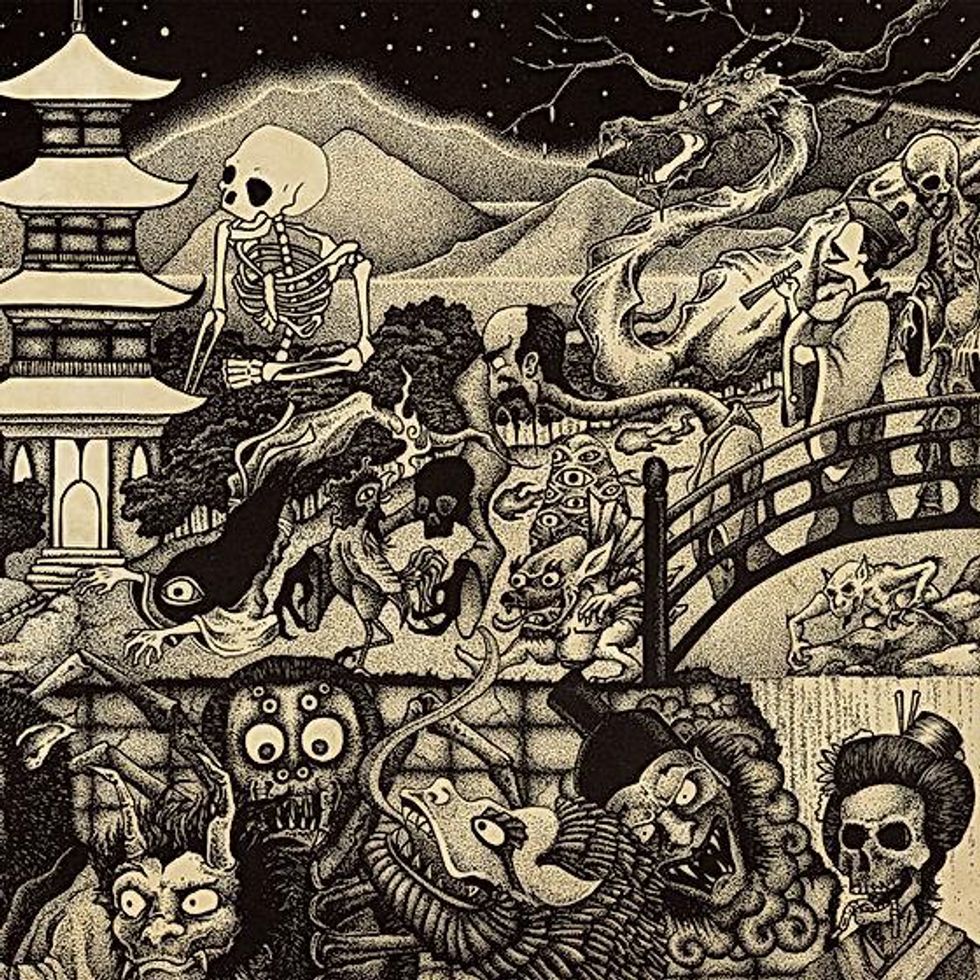

While Mitchell’s commitments with the Crowes have sadly been consistently stymied by complications from the pandemic, Earthless have recently returned to the recorded form with a sprawling, hour-long instrumental adventure: Night Parade of One Hundred Demons. The sinister subject is the musical translation of a story pulled from Japanese folklore about a chaotic night in which the supernatural world collides with our own and a cavalcade of demons runs rampant through the streets of Japan. While the record is entirely instrumental, it’s the band’s first to feature a specific sonic story concept—and it’s one of the most musically intense releases in their discography.

Mitchell explains the album’s unexpected direction: “There’s a darker vibe to it. It could be some frustrations from the pandemic, but we’re pretty light, happy people for the most part. It’s just the music that came out.” The concept came from the band’s bassist. “Mike and his son are really into Japanese folklore and art,” Mitchell explains, “so he brought in the idea of calling it Night Parade of One Hundred Demons and explained the story, and it just made perfect sense with the music we had been writing. Then we were like, ‘Well let’s actually tell that story!’

Night Parade Of One Hundred Demons, Pt. 1

“When we started writing, we noticed that the music was reminiscent of Japanese bands that we loved, like Flower Travellin’ Band, Blues Creation, and Shinki Chen. We just ran with that sound,” explains Mitchell. Those esoteric hard-rock and proto-metal groups that came out of Japan in the late ’60s and early ’70s filtered Western heavy rock through a uniquely Japanese lens, making for music that was fundamentally familiar sounding yet totally exotic, relative to the British and American bands that influenced it. For Mitchell, no one does heavy guitar music quite like the Japanese, and the concept of the album “opened up the possibility of really getting inside of a Japanese scale approach” and guided his note choices in a new direction.

Mitchell says the recording experience “was a fun challenge to try to pay homage to that music” and explains, “a lot of what was going on in my mind—if we can talk in intervals—was like root, flat second, minor third, flat sixes—all of these weird combos that aren’t in your blues scale or your Mixolydian or Dorian things, but more Locrian in nature. It’s a totally different thing.” He adds that he was inspired by traditional Japanese music and instruments like the koto as well.

Night Parade opens with a positively lush six-minute guitar intro that Mitchell says is meant to paint the picture of a Japanese village at sunset. It’s an idyllic, tranquil scene that’s conveyed through passages of delicate, Hendrix-informed clean-toned guitar work. “We paint this pretty picture and then … boom, all hell breaks loose and these demons show up!” Mitchell explains. “The idea was to have more of a direction with it, trying to tell a specific story and putting the music to that story. Nothing else we’ve done has ever had any greater meaning or specific subject attached to it, so this was totally different and was a lot of fun.”

“I try to go into each improvisational section or solo by telling myself, ‘Here’s this moment that is for you. Be very present in it and mean what you’re doing!’”

The arrival of the demons from the Japanese legend is marked by a churning, turbulent, and downright evil-sounding riff fest that puts all of Mitchell’s gifts on full display. On the latter half of “Night Parade of One Hundred Demons, Pt. 1,” his guitar work bridges the chasm between Clapton’s sense of melody and feel and the extreme intensity and hellish string-bending and whammy-bar theatrics of Slayer. Across the album’s three long tracks, the band still has a foot firmly in the blues-rock world, but there’s fuzzed-out mayhem, searing proto-metal lead work, and an element of adventure and danger that is sorely missing from much of today’s improv-based rock ’n’ roll.

Dramatic trem-bar moves haven’t been a calling card for Mitchell in the past, but they’re an important facet of Night Parade’s sonic storytelling. Mitchell explains that aggressive whammy-bar techniques were something he’d avoided in the past, opting to block the bridge of his battered main Strat for years because he could never get the stock trem system to stay in tune. However, for the new record, he says, “We wanted to evoke a feeling, a mood, a sensation—and that required overbearing whammy bar! Totally Jeff Hanneman or Neil Young trying to break his strings at the end of a set, just freaking out! It’s perfect for making a song sound like hell and murder and death and chaos. It’s frantic and it’s anxious and paranoid and a mood of terror.”

Mitchell credits his friend Phil Manley (Trans Am, The Fucking Champs), who recorded the band’s From the Ages album, with changing his attitude. “[He] turned me on to Callaham Guitars, and I got a whole new trem system for my Strat from them. I just slapped that thing on and had it floating a little bit, and all of a sudden I was throwing bigger Hendrix dives into my playing and it wouldn’t go out of tune. I was amazed.” He adds that “it’s like having a totally new guitar. The thing with Earthless is I’m not going to be able to retune in the middle of an hour-long song. You’re fucking out to sea swimming and there’s no stopping.”

Isaiah Mitchell, wielding his go-to Strat, tweaks his Echoplex as Earthless jams.

Photo by Marta Estellés Martín

Night Parade was tracked to tape and a key part of its charm and immediacy is its organic production aesthetic. While the album tells a tale of the spirit world, it still sounds like three humans in a room attempting to blast their way into the void. There’s 60-cycle hum in the clean parts, there’s the obvious sound of air hitting mics, and Mitchell confirms that amps and speakers were indeed harmed in its creation. “We wanted to keep it as real as possible,” he says, “but we also wanted to make it sound great and not deliberately mess it up, but also not over-polish it.”

Rig Rundown - Earthless

As a player who’s spent the lion’s share of his career in improvised music, Mitchell knows how to pull something out of nothing with his guitar. “I try to go into each improvisational section or solo by telling myself, ‘Here’s this moment that is for you, be very present in it, and mean what you’re doing!’” he says. “I don’t want to just shoot notes here and there. I want to really try to play off what everyone else is doing and listen.”

TIDBIT: The concept for Night Parade of One Hundred Demons was inspired by a story that bassist Mike Eginton and his son found in a book of traditional Japanese ghost tales.

It’s no surprise that his inspiration comes from the classics: “What really got me into that approach was listening to Live Cream and Hendrix just taking off forever, really feeling what guys like Clapton and Hendrix, or even Neil Young, had in their phrasing. It’s like they’re breathing, you know? There’s an intention in everything they played. They’re trying to convey something. They want to make you feel something, and it’s just very tasteful and about presence in the moment. That’s the best place to come from when you’re improvising. Building and trying to tell an interesting story melodically—that’s my approach. Tasteful phrasing is about not laying all your cards on the table right away or blowing it all up right out the gate—build it, build tension!”

Mitchell’s dedication to his craft as a player and tone-shaper naturally helped him land his high-profile spot with the brothers Robinson in the revived Black Crowes, and he’s still drinking the experience in. “I was a fan growing up and watched their music videos on MTV, so it’s a really surreal experience,” he ruminates. “I’ve been friends with Chris [Robinson, Black Crowes frontman] for maybe 10 years now, but it’s so cool to be brought into the fold and to play with people that love music like they do. The whole band is fantastic and getting to hear Rich [Robinson, Black Crowes guitarist] and Chris together is a sound and it’s powerful. It’s a wonderful experience musically and getting to play those songs that I grew up with—and being able to put my stamp on it and still honor the song—is important to me.”

“We paint this pretty picture and then … boom, all hell breaks loose and these demons show up!”

He approaches his position in the Black Crowes with the same level of care he brings to his own band. “The fans are used to a certain thing,” he explains, “and you can do too much to bring yourself into it. I don’t think that’s always the right choice.” Contrary to Earthless, which is built around his own creative instincts, Mitchell points out that in such a classic, established band, it’s of utmost importance to know “where and when to be yourself.” And while Earthless calls for a more maximal, up-front guitar sound, playing in the Black Crowes alongside another guitarist and keyboardist is “a totally different way of filling musical space. I love being in different places and playing different roles and trying to be as selfless as possible for the sake of what the music needs.”

As both the longtime lead voice in Earthless and now the guitarist in the Black Crowes, Mitchell has risen from unsung underground guitar hero status into the mainstream. It’s a position he revels in, but he brings respect for the history of the band’s guitar chair. “My favorite part about the Crowes growing up is that the songs were fantastic,” he says, exclaiming, “but I really fucking loved Marc Ford’s playing. He was one of my dudes, growing up!”

The Gear Behind Isaiah Mitchell’s Heroic Tone

Mitchell performs with Earthless in Berkeley, California, at the Cornerstone on February 20, 2022.

Photo by Samuel Cuevas-Coria

Guitars

- ’50s-style Fender Stratocaster

- Gibson Custom Shop 1956 Les Paul Goldtop reissue

- Prisma Guitars custom build (made from recycled skateboard decks)

- Ian Anderson T-Style

Amps

- 1971 100-watt Marshall Super Lead

- 1979 Marshall 2203 JMP

- 1968/1969 Fender Super Reverb

- Vox AC15 head

- Orange Custom Shop 50 head

- Satellite Amps 2x12

- Orange vertical open-back 2x12 with Celestion Creambacks

Effects

- Strymon Flint

- Make Sounds Loudly Klon clone

- Make Sounds Loudly Tone Bender clone

- Make Sounds Loudly Night Witch

- Carlin compressor/distortion clone

- ’90s Fender brown-panel Reverb unit

- Tym Guitars Seaweed Isaiah Mitchell Signature Fuzz

- Maestro Echoplex EP-3

- Dunlop Cry Baby

- Vox wah

- Xotic EP Boost

Strings & Picks

- Dunlop (.010-.046)

- Dunlop .88 mm Tortex

Mitchell has some of the best tones in rock ’n’ roll. On Night Parade of One Hundred Demons, he kept things relatively simple and turned to some classic pieces.

For a clean tone, Mitchell relied upon a Fender Super Reverb from ’68 or ’69, which he sometimes mixed with a Vox AC15 head played through a Satellite Amplifiers 2x12 cab, paired with an Xotic Effects EP boost. He embraced his rig’s natural hum: “That tone just sounds so good and there’s something about hearing that hum that feels organic, and it doesn’t take away anything from the music for me. If you listen to Stevie Ray Vaughan’s ‘Little Wing,’ you can hear his amps humming. It’s organic and I think there’s something beautiful in keeping the recording what it is. You’re getting this beautiful tone and hearing that hum is a piece of that tone.”

To create the record’s burly-but-dynamic distorted sounds—the “full-blown stuff,” as Mitchell calls it—he used his primary 1971 100-watt Marshall Super Lead until it released the magic smoke that all tube amps run on and was placed on the injured list. “It sounded fantastic until it blew up!” the guitarist exclaims. “I’m not sure what happened, but luckily the transformers were fine.” He borrowed a friend’s ’79 JMP 2203 as a replacement. He also occasionally used an Orange Custom Shop 50 through an Orange 2x12 vertical open-back cab loaded with Celestion Creambacks.

For guitars, a thrashed but beloved Fender Strat (with its new Callaham trem and the ’50s style deep-V neck it came with) that Mitchell bought from a friend’s father as a teenager did the heavy lifting. That guitar now sports a set of signature Stratocaster pickups Mitchell concocted with Australian builder Mick Brierley. While Mitchell says the process of arriving at the desired sound involved many prototype sets with too many different spec recipes to recall, he says the pickups they ultimately arrived at are “dialed-in to have a lot more midrange than most Strat sets and are very clear, clean up nicely, and add a lot of warmth to the sound.”

“We wanted to evoke a feeling, a mood, a sensation, and that required overbearing whammy bar!”

Backing up the Strat was a recent ’56 Gibson Custom Shop Les Paul Goldtop reissue loaded with P-90s, which Mitchell used for the album’s beefier riffs. For some of the cleaner sounds, the guitarist also employed a custom build from Prisma Guitars that was made from recycled skateboard decks.

Mitchell shaped his tone with a stash of effects that included a tried-and-true Echoplex EP-3, a standard Vox wah, a Cry Baby wah, a crew of overdrives and fuzzes by Make Sounds Loudly, Mitchell’s signature Tym Effects Seaweed fuzz—based on a Triangle Big Muff circuit—and a reissue of a little-known compressor made by Carlin in the ’60s. “Reine Fiske of Dungen is probably the top dude for me right now. He’s an amazing guitar player and his tone is just impeccable. I was reading interviews with him, and he spoke about the Carlin compressor, so I got a remake of one of those. That’s a really cool pedal that’s noisy and kind of shitty, but in a vintage way that isn’t trying to clean up a bunch of stuff, and you can overdrive it like a fuzz.”

To represent the sound of demons “swirling around each other,” as he puts it, on “Night Parade of One Hundred Demons, Pt. 2,” “I used a Leslie cab to be the sound of one of the demons and then the regular guitar rig to represent the human. Creating a different personality with the Leslie was a fun way to get there.”

EARTHLESS Los Angeles, CA. 2-25-2022

In February, Earthless ripped a blistering set for nearly two hours at the Echo in L.A., presented here in all its psychedelic glory.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)