Great design starts with an idea, a concept, some groundbreaking thought to do something. Maybe that comes from a revelation or an epiphany, appearing to its creator in one fell swoop, intact and ready to be brought into the real world. Or maybe it’s a germ that sets off a slow-drip process that takes years to coalesce into a clear vision. And once it’s formed, the journey from idea to the real world is just as open-ended, with any number of obstacles getting in the way of making things happen.

As CEO, president, and chief guitar designer of Taylor Guitars, Andy Powers has an unimaginable amount of experience sifting through his ideas and, with a large production mechanism at hand, efficiently and effectively realizing them. He knows that there are great ideas that need more time, and rethinking electric guitar design—from the neck to the pickups to how its hollow body is constructed—doesn’t come quickly. His A-Type—which has appeared in Premier Guitar in the hands of guitarists Andy Summers and Duane Denison of the Jesus Lizard—is the innovative flagship model of his new brand, Powers Electric. And it’s the culmination of a lifetime of thought, experience, and influences.

“Southern California is a birthplace of a lot of different things. I think of it as the epicenter of electric guitar.”

“I’ve got a lot of musician friends who write songs and have notebooks of ideas,” explains Powers. “They go, ‘I’ve got these three great verses and a bridge, but no chorus. I’ll just put it on the shelf; I’ll come back to it.’ Or ‘I’ve got this cool hook,’ or ‘I’ve got this cool set of chord changes,’ or whatever it might be—they’re half-finished ideas. And once in a while, you take them off the shelf, blow the dust off, and go, ‘That’s a really nice chorus. Maybe I should write a couple of verses for it someday. But not today.’ And they put it back.”

That’s how his electric guitar design spent decades collecting in Powers’ head. There were influences that he wanted to play with that fell far afield from his acoustic work at Taylor, and he saw room to look at some technical aspects of the instrument a little differently, with his own flair.

The Powers Electric A-Type draws from Powers’ lifelong influences of cars, surfing, and skateboarding.

Over the course of Powers’ “long personal history” with the instrument, he’s built, played, restored, and repaired electric guitars. And, having grown up in Southern California, surrounded by custom-car culture, skateboarding, and surfing—all things he loves—he sees the instrument as part of his design DNA.

“Southern California is a birthplace of a lot of different things,” Powers explains. “I think of it as the epicenter of electric guitar. Post-World War II, you had Leo Fender and Paul Bigsby and Les Paul—all these guys living within just a couple of miles of each other. And I grew up in those same sorts of surroundings.”

Those influences and the ideas about what to do with them kept collecting without a plan to take action. “At some point,” he says, “you need the catalyst to go, ‘Hey, you know what? I actually have the entire guitar’s worth of ideas sitting right in front of me, and they all go together. I would want to play that guitar if it existed. Now is a good time to build that guitar.’”

“I started thinking, ‘If I had been alive then, what would I have made?’ It’s kind of an open-ended question, because at that point, well, there’s no parts catalogs to buy stuff from. A lot of these things hadn’t been invented yet. How would you interpret this?”

The pandemic ultimately served as the catalyst Powers’ electric guitars needed, and that local history proved to be a jumping-off point necessary for focusing his long-marinating ideas. “I started thinking, ‘If I had been alive then, what would I have made?’ It’s kind of an open-ended question, because at that point, well, there’s no parts catalogs to buy stuff from. A lot of these things hadn’t been invented yet. How would you interpret this? As a designer, I think that’s really interesting. Overlay that with understanding what happens to electric guitars and how people want to use them, as well as some acoustic engineering. Well, that’s pretty fascinating. That’s an interesting mix.”

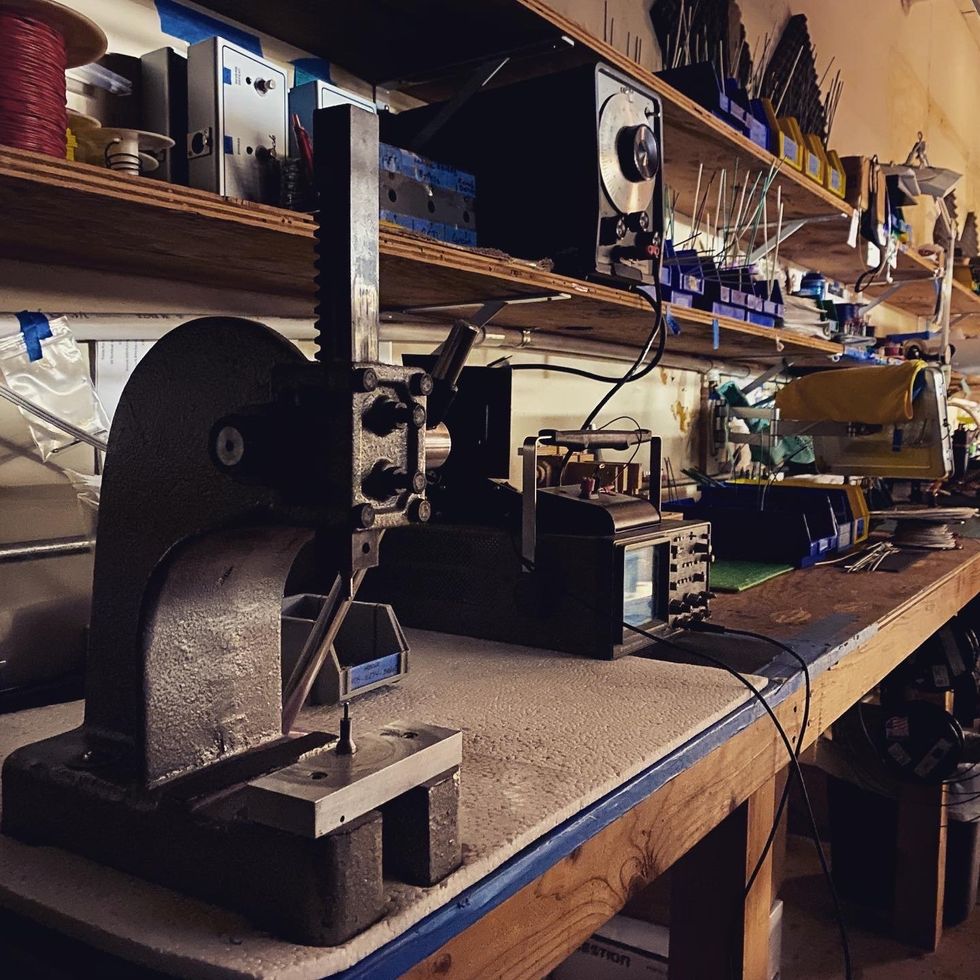

Tucked away in his home workshop, Powers set about designing a guitar, building “literally every little bit other than a couple screws” including handmade and hand-polished knobs. Soon, the prototype for the Powers Electric A-Type was born. “I played this guitar and went, ‘I’ve been waiting a long time to play this guitar.’ A friend played it and went, ‘I want one, too.’ Okay, I’ll make another one. Made two more. Made three more….”

The A-Type—seen here with both vibrato and hardtail—is a fully hollow guitar that is built in what Powers calls a “hot-rod shop” on the Taylor Guitars campus.

From there, Powers recalls that he started bringing his ideas back to his shop on Taylor’s campus, where he set up “essentially a small hot-rod shop” to build these new guitars. “It’s a real small-scale operation,” he explains. “It exists here at Taylor Guitars, but in its own lane.”

The A-Type—currently the only planned Powers Electric model—has the retro appeal of classic SoCal electrics. Its single-cut body style is unique but points to the curvature of midcentury car designs, and the wide range of vibrant color options help drive that home. Conceptually, the idea of reinventing each piece of the guitar’s hardware points toward the instrument’s creators. That might get a vintage guitar enthusiast’s motor running, but it’s in the slick precision of those parts—from the bridge and saddle to the pickup components—where the A-Type’s modernism shines.

“It’s a real small-scale operation. It exists here at Taylor Guitars, but in its own lane.”

Grabbing hold of the guitar, it’s clearly an instrument living on the contemporary cutting edge. The A-Type’s neck gives the clearest indication that it’s a high-performance machine; it’s remarkably easy to fret, with low action but just enough bite across the board. Powers put a lot of thought into the fretboard dynamics that make that so, and he decided to create a hybrid radius. “You have about a 9 1/2" radius, which is really what your hand feels, but then under the plain strings, it’s a bit flatter at 14, 15-ish—it’s so subtle, it’s really tough to measure.” Without reading the specs and talking to Powers, I don’t know that I would detect the difference—and I certainly didn’t upon first try. It just felt easy to play precisely without losing character or veering into “shredder guitar” territory.

The A-Type looks like a solidbody, but you’ll know it’s hollow by its light, balanced weight. That makes it comfortable to hold, whether standing or sitting. But its hollow-ness is no inhibitor to style: I’ve yet to provoke any unintended feedback from any of my amps. Powers explains that’s part of the design, which uses V-class bracing, similar to what you’ll find on a modern Taylor acoustic.

Powers says the A-Type that is now being produced is no different than the prototype he built in his home workshop: “I have the blueprint, still, that I hand drew. I can hold the guitar that we’re making up against that drawing, and it would be like I traced over it.”

“Coupling the back and the top of the guitar matter a lot,” he asserts. “When you do that, you can make them move in parallel so that they are not prone to feeding back on stage. You don’t actually have that same Helmholtz resonance going on that makes a hollowbody guitar feedback. It’s still moving.”

On a traditional hollowbody, he points out, the top and back move independently, compressing the air inside the body. “It’ll make one start to run away by re-amplifying its own sound,” he explains. “But if I can make them touch each other, then they move together as a unit. When they do that, you’re not compressing the air inside the body. But it’s still moving. So, you get this dynamic resonance that you want out of a hollowbody guitar; it’s just not prone to feedback.”

What I hear from the A-Type is a rich, dynamic tone, full of resonance, sustain, and volume. I found it to be surprisingly loud and vibrant when unplugged. Powers tells me that’s in part due to the “stressed spherical top” and explains, “I take this piece of wood and I stress it into a sphere, which unnaturally raises its resonant frequency well above what the piece of wood normally could. It’s kind of sprung, ready to set in motion as soon as you strike the string. So, it becomes a mechanical amplifier.” The bridge then sits in two soundposts, which Powers says makes it “almost like a cello.”

“Literally every little bit other than a couple screws” on the A-Type is custom made.

The single-coil pickups take it from there. They’re available in two variations, Full Faraday and Partial Faraday, the latter of which were in my demo model, and Powers tells me they are the brighter option. Their design, he says, has been in progress for about seven or eight years. The concept behind the pickups is to use the “paramagnetic quality of aluminum”—found in the pickup housing—“to shape the magnetic field … which functions almost like a Faraday cage.” And he complements them with a simple circuit on the way out.

I found them to run quietly, as promised, and offer a transparent tone with plenty of headroom. They paired excellently with the ultra-responsive playability and feel of the guitar, so I could play as dynamically as I desired. If a standard solidbody with single-coils offers the performance of a practical sedan, this combo gave the A-Type the feel of a well-tuned racecar. At low volumes and with no pedals, it felt like I was simply amplifying the guitar’s acoustic sound, and I had full control with nothing but my pick. (Powers explains that the pickups have a wide resonance peak, which plays out to my ear.) Add pedals to the mix, including distortion and fuzz, and that translates to an articulated, hi-fi sound.

Now up to serial number XXX, the Powers Electric team has refined their production process. I wonder about that first guitar, the dream guitar Powers built in his house. How similar is the guitar I’m holding to his original vision? “It’s very, very, very close,” Powers tells me. “Literally, this guitar outline is a tracing. It’s an exact duplicate of what I first drew on paper with a pencil. I have the blueprint, still, that I hand drew. I can hold the guitar that we’re making up against that drawing, and it would be like I traced over it.”

“It’s one of those things you do because you just really want to do it. It puts some spark in your life.”

Playing the guitar and, later, talking through its features, I’m left with few questions. But one that remains has to do with branding and marketing, not the instrument: Why go to all the effort to create a new brand for the A-Type, which is to say, why isn’t this a Taylor? For Powers, it’s about design. “As guitar players,” he explains, “we know what Taylor guitars are, we know what it stands for, and we know what we do. The design language of a Taylor guitar is a very specific thing. When I look at a Taylor acoustic guitar, I go, ‘I need curves like this, I need colors like this, I need shapes like this.’”

Those aren’t the same curves, colors, and shapes as the Powers Electric design, nor do they mine the same influences. “There’s a look and a feel to what a Taylor is. And that is different from this. I look at this and go, ‘It’s not the same.’”

Of course, adding the A-Type to the well-established Taylor catalog would probably be easier in lots of ways, but Powers’ positioning of the brand is a sign of his dedication to the project. It feels like a labor of love. “They’re guitars that I really wanted to make,” he tells me enthusiastically. “And I’m excited that they get to exist. It’s one of those things you do because you just really want to do it. It puts some spark in your life.”

“It’s like a solo project,” he continues. “As musicians, you front this band, you do this thing, and you also like these other kinds of music and you’ve got other musician friends, and you want to do something that’s a different flavor. You try to make some space to do that, too.”

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)