Pickups are simple devices with only a few parts: magnets, wire, bobbins or coil-formers, and mounting hardware. But those parts interact in endlessly complex ways. Even a small change in materials, measurements, or physical layout can have massive effects on tone. Given that, it's hardly surprising that we have so many different pickups to choose from, each with a unique voice.

Yet a few designs tend to command most of our attention. It's no mystery why humbuckers, P-90s, and Fender single-coils are so popular: They sound excellent, perform consistently, and are suitable for many musical styles. But here we'll sidestep those universally admired classics and focus on a half-dozen great-sounding vintage models from the 1950s and '60s that have never quite gotten their due.

doing that all day?" —Curtis Novak

The good news is, originals tend to appear in relatively affordable guitars. Most are also available in historically accurate modern reproductions, thanks to the efforts of manufacturers who love the old designs enough to resurrect them even though they may never be top sellers. As Curtis Novak, one of the experts I spoke to while preparing this story, said: “I make a killer Strat pickup, but where's the fun in doing that all day?"

Pickups appear in alphabetical order, not ranked by coolness. They're all cool.

Burns Tri-Sonic

There's a fine line between gimmick and innovation, and James Ormston Burns was often on the border. Ormston Burns Ltd. started guitar production in 1960 with the Tri-Sonic- equipped Vibra-Artist model. He continued producing guitars, many quite futuristic-looking, throughout the decade.

Burns on YouTube

Cliff Richard & The Shadows Live from Belgium. The Shadows play Tri-Sonic-equipped Burns through their Vox AC30s. Check out lead guitarist Hank Marvin on “Sleepwalk" at 34:00.1963 was a busy year at the newly opened Burns showroom in London's St. Giles Circus. Burns refinished John Lennon's honey-colored Rickenbacker 325, making it black and adding Burns knobs. (The Beatles' George Harrison can be seen playing a Burns Nu-Sonic Bass during 1966's “Paperback Writer" and “Rain" sessions. Not having a right-handed bass, the band rented the instrument for the sessions.)

Burns on YouTube

Cliff Richards, “On the Beach"Also in 1963, Brian May and his dad built the iconic Red Special, the guitar May would eventually play with Queen. After an unsuccessful attempt to make his own pickup, May purchased three Tri-Sonic pickups for his homemade guitar from a rather skeptical Burns sales clerk.

Burns on YouTube

The Searchers, “When I Get Home"That same year the company launched their Split Sound pickups. These incorporated separate coils for the pole pieces of the upper and lower strings, allowing independent bass/treble adjustment. They also struck a deal with Ampeg to export Ampeg-branded, Burns-made guitars to the States. However, shipping costs made the guitars pricey, and the agreement ended by 1965. That was the year Baldwin took over Burns, leading to a reduction in quality and the brand's 1970 demise.

Burns's marketing was as unique as their pickups. In one 1964 promotion, 70 Burns guitars were given away to breakfast-munching rockers who responded to a contest posted on Kellogg's Rice Krispies boxes.

Burns on YouTube

Queen “Somebody to Love" Official Video. Check out Brian May's solo at 2:10.Burns Guitars is currently run by one of James Ormston Burns' biggest fans, Barry Gibson. He formed Burns London Ltd. to revive the brand's former glory. He's particularly enthusiastic about Tri-Sonic pickups, which appear on many current Burns models. According to Barry Gibson, “The most unique feature of the Tri-Sonic, and the reason for its name, is that it picks up sound from three points: the top and both sides." This means that the pickup “hears" a longer-than-usual length of string. The result, claims Gibson, is a uniquely “big, round sound." We don't know whether this was a design feature or an unintended byproduct, but if it was an accident, it was certainly a happy one.

Burns on YouTube

Queen “We Will Rock You." Guitar enters around 1:30.One reason Tri-Sonics remain “sleepers" today is because of their size. You can't install one in a Strat, for example, without enlarging the pickup rout. That's why Barry Gibson and his company have created the Tri-Sonic Mini, which they say offers the original sound in a Strat-sized footprint. Burns has been making Minis in small production runs for several years, and they're currently gearing up for heavier production in hopes of “waking up" this sleeper.

Photo courtesy of Curtis Novak

Franz Single-Coils

Guild made extremely desirable guitars in the 1950s. The company's electric line included archtops as well as the Les Paul-like Aristocrat. But if you refer to their pickups as P-90s, Guild fans will immediately point out that they were in fact made by Franz.

Guild started guitar production in 1953 (though they didn't assign model numbers until the following year). Franz pickups appeared on the early X-series archtops and the Aristocrat. Guild's higher-end archtops had three pickups with pushbutton selector switches like those in early Epiphones. This was no coincidence—Guild was founded by former Epiphone employees who opted not to follow the company when it moved from New York City to Philadelphia.

Franz pickups were manufactured in Astoria, Queens. Guild did not have exclusive rights—Franz sold pickups to other guitar manufacturers as well. They were very much handmade items, and somewhat crudely handmade at that. The bobbins were glued together, not molded, using a type of vulcanized rubber. The top and bottom bobbin pieces were cut at the corners to avoid snagging while winding. Unlike most of the day's manufacturers, Franz had the foresight (at least for a time in the early 1950s) to create separate models for the neck and bridge, spacing the pole pieces accordingly.

Armed with that info, you can confidently point to an old Guild and say, “Those aren't P-90s." Except that, for most practical purposes, they are. Like the P-90, the Franz pickup has two side-by-side bar magnets positioned below the coil. Separating the magnets are the lower portions of the adjustable pole pieces, six 5/40 Fillister-head screws. The magnets sit on a metal base that folds up slightly at the sides.

Franz on YouTube

A Franz-equipped Guild can be heard in Dave Gonzalez's hands on The Paladins “Daddy Yar"

Curtis Novak, who dissected many Franz pickups in preparation for his current reproduction, encountered widely varying readings from vintage models. Typical values are 4.6k for a neck pickup and 4.9k for a bridge, but some units have DC resistance into the 8k range. Was it simply a matter of too much workday chitchat among Franz employees when they should have been counting their windings? Perhaps, but that range seems too wide to be accidental. More likely it's due to the fact that while many Franz pickups were destined for Guild's large-body archtops, others were being readied for solid bodies. Pickups with lower readings were probably wound for mellow jazz box tones. Those jazzers would have been likely to use heavy-gauge flatwounds. Pickups with higher DC resistance may have been deliberately wound for rock guitarists.

Franz bobbins differ slightly from those in P-90s. And according to Seymour Duncan, Franz magnets tend to be relatively weaker and not as loud, though weaker magnets can provide a smoother sound.

By 1959 DeArmond pickups started replacing the Franz pickups on some Guilds. Original Franz pickups are long out of production, though Novak offers accurate reproductions.

Photo courtesy of Curtis Novak

Gibson Alnico V “Staple"

Enter your vast, climate-controlled guitar closet and open the case housing your mint-condition 1954 Les Paul Custom in tuxedo-matching black. In the neck position you'll see a Gibson Alnico V pickup, complimenting a P-90 pickup at the bridge. Developed by the late Seth Lover around 1952 or '53, the Alnico V was a louder version of Gibson's earlier single-coil, the P-90. While the era's gold, maple-topped Les Pauls sported a pair of P-90s, the mellower, all-mahogany Custom benefitted from the brighter-sounding (and cool-looking) Alnico V.

(The pickup gets its name, of course, from the alloy of aluminum, nickel, and cobalt melded with iron to form the magnets in many guitar pickups. There are many alnico variations, each denoted by a number, though alnico 2 and 5 are most common in guitar pickups.)

the neck and bridge positions.

Gibson also installed Alnico Vs in their L-5 and Super 400 models, using a dog-eared version appropriate for archtop mounting. Gibson officially designates it the “480" pickup—the “staple" moniker comes from the appearance of its square magnets, chosen by Lover in a deliberate attempt to visually differentiate the pickup from DeArmond's Model 200 pickup (later known as the Dynasonic). Cosmetics aside, the two pickups are very similar.

Seymour Duncan describes the Alnico V as having more output and clarity and a “tighter" tone relative to the P-90. Duncan also notes that it's well suited for the relatively dark tone mahogany produces. The two models are quite different in construction: While a P-90 has bar magnets at its base and adjustable screws for pole pieces, the Alnico V's square pole pieces are the magnets. Fine, old-school 1950s mechanical engineering resides within: In addition to offering a unique look, the square magnets allow space for six pole piece-adjustment screws. Like a DeArmond 200, the adjoining screws connect to an underlying spring mechanism, enabling individual pole piece height adjustment. The intricate yet effective design is evident when viewing the pickup from the bottom.

Gibson Alnico V “Staple" on YouTube

Scotty Moore's 1954 Gibson L5 CESN, purchased for $565 in 1955, came with Alnico V pickups in both the neck and bridge positions. Check out his sound on Elvis Presley's “Mystery Train," the Presley band's rendition of Carl Perkins's “Hound Dog" on the July 2nd, 1956, episode of The Milton Berle Show

Compared to a Fender single-coil pickup, the Alnico V incorporates a flatter but wider bobbin with more windings, giving it higher DC resistance. Meanwhile, stronger magnets provide more output. A Strat pickup might have DC resistance of 6.3k with 40 to 50 gauss, while an Alnico V is around 8.6k with more than 50 gauss.

The Alnico V/Les Paul relationship was relatively short-lived—by 1957 Les Pauls featured Lover's new humbuckers. But the Alnico V wasn't quite extinct—it reappeared in the 1970s and again in the 2000s in reissues of the 1955 Les Paul Black Beauty. But these days, the Alnico V is chiefly a custom shop specialty.

Gibson Alnico V “Staple" on YouTube

Here's the group's April 3, 1956, performance of Carl Perkins' “Blue Suede Shoes" before crewmen of the USS Hancock

A close relative to the Alnico V, according to Gibson master luthier Jim DeCola, is a P-90 that appeared in 1946 on the ES-125. That version used round magnets (probably alnico 2) for the pole pieces, not the steel adjusting screws typical of P-90s. (The 1946 P-90 wasn't exactly the same—the larger rectangular cross-section of the Alnico V puts the magnets' edges closer to the coil.) That 1946 cousin, now called the P-90S, is found on the new budget-conscious Les Paul Melody Maker.

Seymour Duncan makes a faithful Alnico V reproduction, though Duncan concurs that the pickup was originally conceived as a DeArmond clone—a fact confided by his longtime friend, Alnico V creator Seth Lover. That, says Curtis Novak, is why he doesn't make an Alnico V reproduction. “People ask me why," he says. “It's because it's essentially a Dynasonic."

Photo courtesy of Curtis Novak

Gretsch Hilo'Tron

If you love twangy surf and rockabilly, Gretsch's Hilo'Tron may be the pickup of your dreams.

Gretsch introduced their iconic Filter'Tron “Electronic Guitar Head" (as in tape recorder head) at the 1957 summer NAMM show in Chicago. Gretsch migrated from the DeArmond single-coil they'd been using to their own version of the Chet Atkins-inspired, Ray Butts-designed Filter'Tron. Like Gibson's newfangled humbucker, it derived its name from the fact that it filtered out electronic hum, and like Gibson's pickup, it relied on a double-coil design. The Filter'Tron put Gretsch in the pickup-making business, at least for use in their own guitars, and to this day, the Filter'Tron is Gretsch's best-known pickup.

But the company also developed their own single-coil pickup, the Hilo'Tron, which appeared in less expensive Gretsch models such as the Tennessean and Anniversary.The Hilo'Tron was designed to make efficient use of parts that Gretsch already had in stock. Essentially, it's half of a Filter'Tron, with one coil instead of two. The magnet that lies beneath the dual coils in the Filter'Tron is instead mounted to an angled steel plate that houses the coil and six pole piece screws. On the other side of the bar magnet is a vertical steel blade (or magnet keeper).

—Tom “TV" Jones

The Hilo'Tron is wound with thinner magnet wire than the Filter'Tron. Hilo'Trons from the 1960s typically have DC resistance from 2.9k to 3.4k. The pickup also has a lower profile relative to the Filter'Tron because of its side-mounted magnet. This permitted surface mounting on Gretsch's archtops.

Hilo'Trons have a reputation for sounding thin, and many guitarists have dismissed them as less desirable second cousins of the Filter'Tron. But hold on there, cowboy—when did twang go out of style? In fact, Gretsch pickup guru Tom “TV" Jones cites the Hilo'Tron as one of his favorite pickups. He suggests that if you've had a bad experience with one, it probably wasn't properly adjusted. Jones's advice is to not raise the individual pole pieces too high, but keep them just above the level of the pickup's plastic top, arranged in a slight arch that mirrors the fretboard's radius. The poles pieces beneath the wound strings should be slightly higher than those beneath the plain strings. Once those adjustments are made, jack up the pickup with rubber or foam underneath, bringing the entire assembly closer to the strings. (Jones recommends the same technique for Filter'Trons.)

Curtis Novak compares the Hilo'Tron's underlying plate to an earthquake on rocky ground: “The whole earth just shakes." With the coil sitting on a big steel plate, it gets excited from multiple directions. Also, as Seymour Duncan notes, Gretsch players have a tendency to use relatively heavy-gauge strings, adding to this electromagnetic excitement.

Photo courtesy of Tim Mullally of Dave's Guitar Shop.

Hilo'Trons have always had fans, and they are regularly “rediscovered" as great-sounding single-coils. They have a strong Beatles association thanks to George Harrison's Gretsch Tennessean, but they're also nice for now. As Tom “TV" Jones notes, “Properly adjusted and running through a Marshall with a gain pedal, Hilo'Trons are amazing."

Comparing a Hilo'Tron to a Strat single-coil reveals many differences. The Strat's cylindrical magnets create a clear, defined tone. Hilo'Trons, with their thinner magnet wire, bar magnet, internal steel, and steel set screws, are softer in the highs, with a wonderfully clanky '60s-style resonance.

The Hilo'Tron is popular enough for TV Jones to make reproductions. His bridge version has wider pole-to-pole spacing to accommodate the slightly wider string spacing near the bridge. Neck pickups are wound to stock vintage specs, with 3.4k DC resistance, while bridge pickups are wound to a hotter 4.3k for better balance. Multiple mounting options are available.

Photo courtesy of Ken Calvet.

Supro Vista-Tone

After recording the 1958 instrumental classic “Rumble," Link Wray got a new guitar. Out went Rumble's Les Paul, which had become too heavy for Wray due to health issues, and in came the Supro Duo-Tone that would appear on many of his recordings for the Swan label. Few guitarists would consider a '60s Supro to be an upgrade from a '50s Les Paul. But not everyone appreciates the Supro's unique sound.

Chicago's Valco company made guitars and amplifiers under a variety of names. (They made amps for Gretsch and Harmony, among others.) Their best-known guitar brands were Airline and Supro—affordable axes for players on a budget who still wanted to rock.

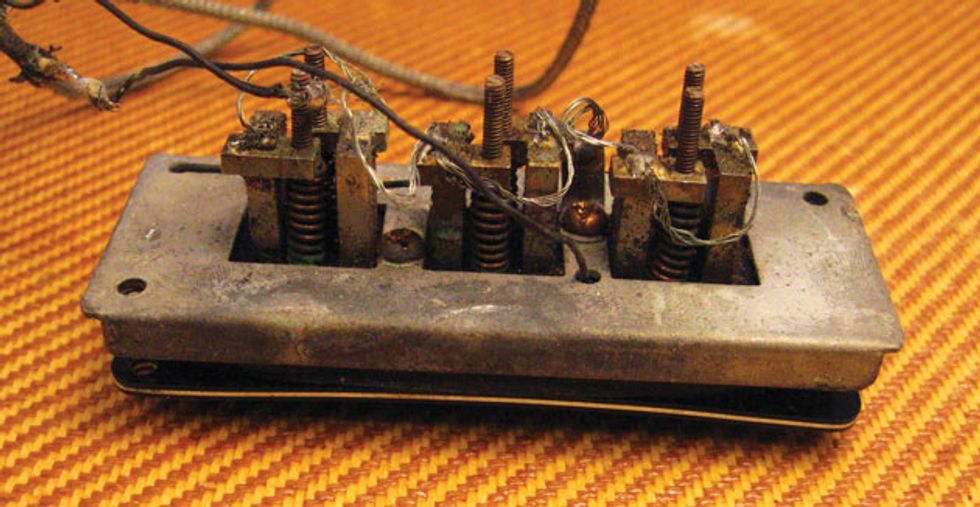

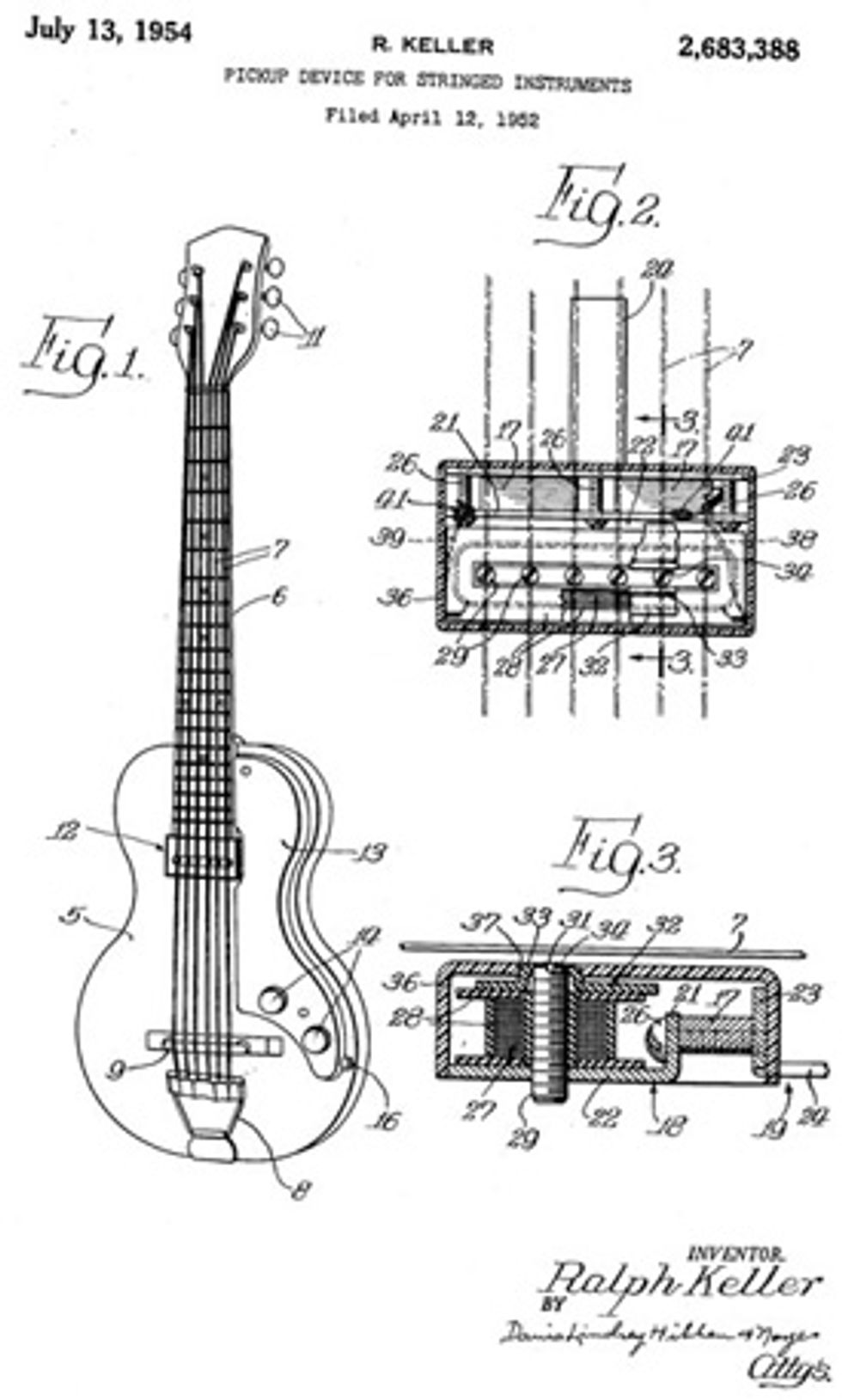

Supro's standard pickup was dubbed the Vista-Tone. It appears to be a humbucking pickup, but it's just an illusion—it's a single-coil dressed as a dual-coil. The Vista-Tone's internal configuration resembles that of the single-coil Gretsch Hilo'Tron, with magnets to one side of a single coil, separated from it by a steel “keeper." Its six pole pieces are height-adjustable screws. According to inventor Ralph Keller's 1952 patent, “An object of this invention is to provide a pickup device which establishes a magnetic field extending for a substantial distance along each string, with the magnetic lines of force lying substantially parallel to the strings for the major portion of said distance." The wide magnetic field spans the width of the housing, interacting with approximately two inches of the strings' length.

A second objective was to keep it cheap. In early versions the Vista-Tone's bobbins were cardboard, though Valco eventually switched to plastic.

These pickups have devoted followers. Luthier Paul Rhoney tried to convince Ken Calvet of Roadhouse Pickups to study Vista-Tones. “Paul kept bugging me," recalls Calvet. “I didn't have an original, but Paul found one for sale." Calvet was soon hooked. He reverse-engineered the design and launched a reproduction run within a few months.

Engineers have a good day when parts from one product can be repurposed for another. At Valco that meant borrowing parts from the already inexpensive Vista-Tone for an even less expensive pickup. That new pickup, a humbucker-size housing with a single attachment screw at its center, appeared in Supro's Kingston guitar. This “Kingston" pickup (Roadhouse's moniker, since Valco seems not to have given it an official name) moves the side-mounted magnets of the Vista-Tone to the center of the coil. There are no pole pieces, and there's less metal. The pickup's sound is closer to that of a Fender single-coil, and the design looks way cool.

But the Vista-Tone remains the star of the family. When pressed, Calvet describes the tone as a cross between a Strat and a P-90, though he says it breaks up differently when pushed: “There's more fuzz around the edges, though they sound good clean too."

Dan Auerbach of the Black Keys often plays a Vista-Tone-loaded Supro, as does Jack White.

Roadhouse has an array of Vista-Tone clips on their site (https://www.roadhousepickups.com/clips/).

Photo courtesy of Curtis Novak.

Teisco “Gold Foils"

There's a chance that some of you older players haven't tried a set of gold foil pickups since the Eisenhower administration. It's well worth giving them another listen.

Two original manufacturers are associated with pickups nicknamed “gold foils": Teisco and DeArmond. Both types have followings, though the pickups differ in construction and sound. Here we focus on the Teisco version.

Something interesting happens when you start to write an article on lesser known pickups: Ry Cooder's name comes up a lot, as does his “Coodercaster," a Stratocaster with an Oahu (Valco) lap steel “string-through" pickup at the bridge and a gold foil at the neck.

Around 1964 young Cooder picked up a Stratocaster from the Fender factory, but after several years he became dissatisfied with the sound of the stock bridge pickup for slide work. His solution was to install a steel guitar pickup. Years later pickup maker David Lindley suggested using a Teisco pickup at the neck. Cooder's combination of flatwounds and pickups inspired many imitators, and those near-forgotten Teisco pickups acquired new respect.

You don't have to play like Cooder to get good results from this pickup. According to pickup manufacturer Jason Lollar, gold foils are shockingly versatile. He says that customers had asked about them for years, but that he only got serious about them when Stooges guitarist James Williamson gave him one to check out. Now Lollar makes an excellent reproduction. It wasn't easy, he says: “There were a lot of parts that needed to be made." Lollar and his team first auditioned their reproduction in an inexpensive Epiphone Les Paul. (According to Lollar, “Gold foils make cheap guitars sound great.")

The pickup actually uses cheap rubber magnets—think refrigerator magnets, only fatter. Their wire is 44-gauge, with around 30 percent fewer turns than a Strat pickup. The bobbin is a mere 1/8" tall. But there's a lot of steel inside, which expands the magnetic field. The pole pieces are adjustable screws to the side of the coil.

A shot of Jason Lollar's current-production Gold Foils.

Viewed from the top, the coil and magnet sit between six big, round holes and two long “racetrack" holes. The screws are “north" of the coil, which means they sense more of the string, providing strong lower overtones. This wide frequency response helps gold foils sound loud and un-muddy.

Gold foils sometimes need shimming to achieve proper height and output, and Lollar's website, lollarguitars.com, has very useful instructions for doing so. As with Gretsch Hilo'Trons, you shouldn't simply adjust the pole pieces—it's better to adjust the height of the entire assembly. Lollar also makes a version that fits in a P-90 housing.

Curtis Novak tends to prefer DeArmond gold foils because their massive steel plates provide a bigger magnetic field that brings in more of what he calls “string wag." Like the Teisco version, this is a big departure from a Fender-style single-coil, where, notes Novak, “there's nothing going on outside the rods."

Want to hear more? Jason Lollar recommends keeping your eyes trained on the guitarists in rowdy rock-band scenes from obscure 1960s biker movies. Apparently they often play guitars with gold foils. Who knew?

Thanks to everyone who helped with this article, including Jason Lollar, Derek and Seymour Duncan, Tom (TV) Jones, Jim DeCola at Gibson Guitars, Barry Gibson at Burns London, Curtis Novak, Frank Meyer, Ken Calvet at Roadhouse Pickups, and Paul Rhoney.