Photo by Andy Ellis.

Look at the back of any all-tube amp, and you’ll see warmly glowing glass bottles in a variety of shapes and sizes. Power tubes (aka output tubes) are typically the biggest ones of the bunch, and they provide the last stage of amplification for the guitar signal before it’s delivered to the speakers. The “power tube” name is a bit deceptive, however, because these big bottles don’t just power your speakers—they actually play a significant role in shaping your amp’s sound and responsiveness.

Regardless of its manufacturer, each power-tube type—EL34, EL84, 6L6, 6V6, 5881, etc.—has a basic sonic personality. Getting to know those tonal characteristics can be a huge help, whether you’re trying to track down a new amp with specific sonic traits, or just wondering whether you can change the sound and feel of an amp you own by using different power tubes (see the Swapper’s Delight sidebar).

To represent the signature sounds of the most popular tubes, I’ve relied on classic rock examples from the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. I don’t mean to suggest that tube amps are only good for playing classic rock. But during that era, there was a greater separation between American and British sounds. Also, players used few, if any, effects in those days, so you can often hear the sound of a guitar plugged directly into an amp, providing clear examples of the core sounds associated with each tube type.

Be sure to check out the power-tube comparison video we also created so you can hear the differences between each tube type.

Warning:

All tube amplifiers contain lethal voltages. The most dangerous voltages are stored in electrolytic capacitors, even after the amp has been unplugged from the wall. Before you touch anything inside the amp chassis, it’s imperative that these capacitors are discharged. If you are unsure of this procedure, consult your local amp tech.

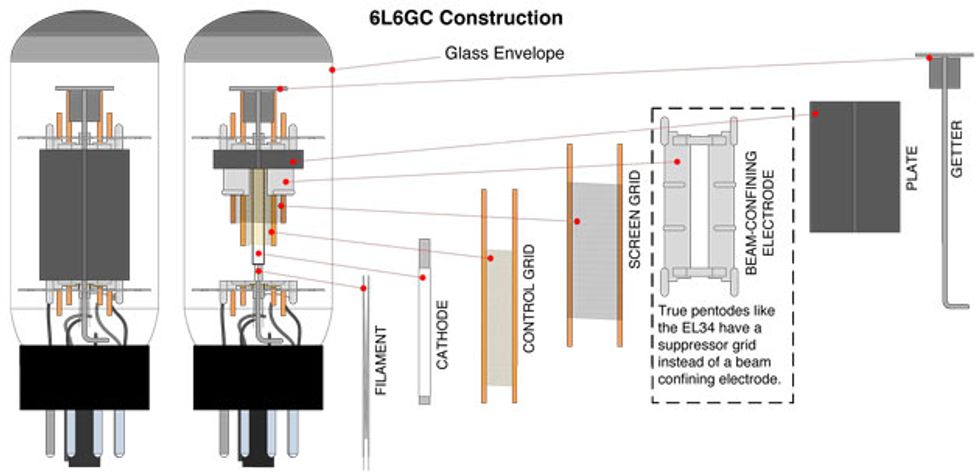

Figure 1. This diagram of a 6L6GC illustrates the main parts found in the power tubes we’re discussing.

Tech Talk: Anatomy of a Power Tube

A power tube is essentially a control valve used to regulate the flow of electrons. (This is why guitarists across the Atlantic refer to our little glass friends as “valves” rather than “tubes.”) The electrons flow from a part of the tube called the cathode to the tube’s plate, as shown in Figure 1. While all power tubes have a cathode and a plate, much of each model’s sonic character is due to its specific components and construction.The power tubes we’re discussing here fall into three categories: tetrode, pentode, and beam power. Tetrode tubes have four electrodes—the aforementioned cathode and plate, as well as a control grid and screen grid. When you turn on your tube amp, the tube filament at the center of the bottle receives a voltage (usually 6.3V) that heats the cathode to free up electrons in preparation for current flow. The plate and screen are given large positive DC voltages to attract the electrons from the cathode to the plate. When your amp is in standby mode, the plate and screen voltages are removed to keep the electrons from flowing, while keeping the cathode warm for instant current flow at any moment.

The control grid is given a negative DC voltage that restricts the flow of electrons from the cathode to the screen and plate. When the control-grid voltage is made more negative, electron flow from cathode to plate is reduced. When the control grid is made less negative, electron flow increases.When electrons from the cathode hit the plate, other electrons from the plate may become dislodged and flow to the screen grid, a phenomenon called secondary emission that reduces the efficiency of the tube

Pentode and beam power tubes add an additional electrode between the screen grid and plate to reduce the occurrence of secondary emissions. Pentodes add a grid called the suppressor grid, while beam power tubes usually add a beam-confining electrode instead.

Photo by Tom Moberly.

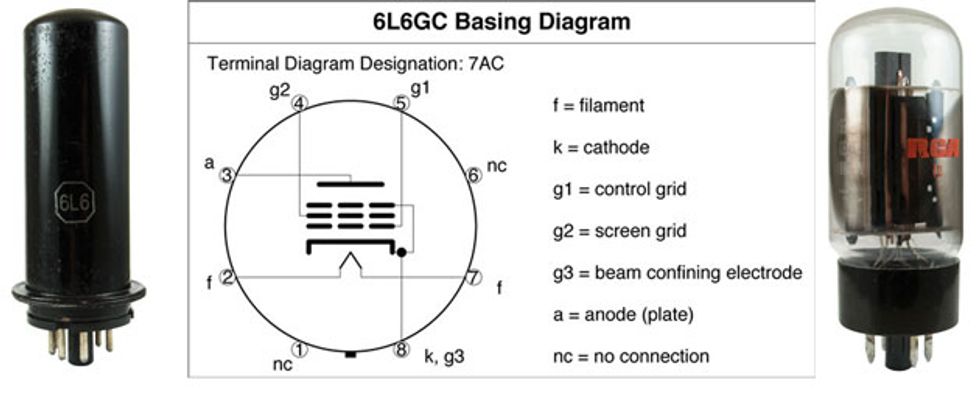

6L6GC

- NOS electrical specs (GE essential characteristics)

- Classification by construction: “beam power amplifier”

- Filament volts: 6.3 V

- Filament current: 0.9 A

- Max plate volts and watts: 500 V, 30 W

- Max screen volts and watts: 450 V, 5 W

The 6L6 was introduced in the 1930s and made in the United States. Early on it was primarily used in radio sets, with a metal envelope to prevent breakage. Revisions to the original 6L6, such as glass envelopes and increased power handling, yielded new designations such as 6L6G, 6L6GA, 6L6GB, and finally the 6L6GC (introduced in the late 1950s). Because of its superior power handling and efficiency over the earlier 6L6 versions, modern tube manufacturers only make the 6L6GC. As a result, most guitarists and some manufacturers simply refer to the 6L6GC as “6L6.” If you plan on buying a new-old-stock (NOS) 6L6GC, be careful not to order the original, metal-tube 6L6—which will likely sound bad and won’t be able to take the heat from your guitar amp.

1960s Fender Blackface Twin Reverb. Photo courtesy of Tim Mullally and Dave's Guitar Shop.

The 6L6GC is commonly associated with classic American rock ’n’ roll and the sound of vintage Fender amps. It was Fender’s tube of choice in the ’60s for such higher-powered amps as the Bassman, Showman, and Twin Reverb. For a great demo of the 6L6GC sound from back in the day, check out Dick Dale and the Del-Tones’ 1963 performance of “Miserlou.” (See the “YouTube It” sidebar for links.) The lows come through fat, punchy, and strong. Mids are tight, articulate, and warm, accented by top-end chime. The 6L6GC does not break up easily—and when it does, the overdrive sound is thick and tight.

The KT66 and 5881 are common substitutes for the 6L6GC. Developed in the late 1930s as Great Britain’s rival to the American 6L6, the KT66 was used in many Marshall amps from the early to mid 1960s. Most believe that Eric Clapton recorded “Hideaway” with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers in 1966 using a Marshall JTM45 with KT66s. Clapton found his sound during this era using a Les Paul’s bridge pickup, maxing-out the volume on the guitar and the volume and bass on the amp for a uniquely fat overdrive sound with much bite and sustain. Try a KT66 in place of the 6L6GC for a slightly cleaner sound.

The 6L6GC is commonly associated with classic American rock ’n’ roll and the sound of vintage Fender amps. It was Fender’s tube of choice in the ’60s for such higher-powered amps as the Bassman, Showman, and Twin Reverb. Photo courtesy of Tim Mullally of Dave's Guitar Shop.

The 5881 predates the 6L6GC. It was introduced in the early 1950s as a smaller, more rugged version of the 6L6G for military use. The 5881 was used in Fender’s famous tweed Bassman, whose circuit was copied for the earliest Marshall amps. (These are probably the tubes Buddy Holly had in his Bassman.) Try the 5881 in place of a 6L6GC to reduce low-end frequency response and get easier breakup into overdrive.

An ammeter

Swapper’s Delight

Swapping out power tubes is much trickier than with preamp tubes. Preamp tubes like the famous 12AX7 are cathode biased, which allows the tubes to automatically adjust themselves if one tube runs a little “hotter” (with more plate current) or “cooler” (less plate current) than another. (If you’re in for some preamp-tube-swapping fun, download our comprehensive PDF comparing tonal characteristics of 23 different 12AX7s on the market today.) If your amp also has cathode-biased power tubes, you can simply plug in a new tube of the same type (or a direct substitute) without needing a bias adjustment—just like with a new preamp tube.Before we talk more about ways you can swap your amp’s power tubes with a different type, let’s discuss biasing in a little more detail. Most higher-powered amps (20 watts or more) have a fixed bias, because it’s more efficient and gives the amp more power output. The drawback with fixed bias is that the tubes cannot automatically adjust themselves. They require a bias adjustment if they run a little hotter or cooler than the optimal setting. Many compare biasing an amp to tuning up a car, because the term refers to the tubes’ “idle” setting, and optimal settings vary from tube to tube. Some amps feature self-adjusting bias. Others have a fixed setting you can adjust via an internal bias pot. Others are simply fixed—i.e., not adjustable.

With a fixed-bias amp, it’s a good idea to check the bias whenever you change power tubes. Even tubes of the same type can run a little hotter (i.e., with more plate current) or cooler (with less plate current) in the same amp—even if they’re the same brand. Many people prefer to use electrically matched power tubes and adjust the bias each time they change them, seeking an ideal bias point for sound quality and tube longevity.

All right, now let’s get back to the idea of swapping tube types. With the exception of the EL84 and its nine-pin miniature base, all of the power tubes mentioned in this article have eight-pin octal bases and can fit into the same tube sockets. However, just because they seem interchangeable doesn’t mean you can randomly plug different power tube types into an amp not designed for them! Doing so risks damaging the circuit.

Yellow Jackets YJS converter.

For example, let’s say you have an amp designed to use four 6L6GC power tubes, and you want to hear what it sounds like with four KT77s. Four 6L6GCs draw about 3.6 amperes (or amps, denoted by the mathematical symbol A) of current from the power transformer’s 6.3 volt (V) filament winding (0.9 A x 4 = 3.6 A), while four KT77s draw about 5.6 A (1.4 A x 4 = 5.6 A). If your amplifier’s power transformer isn’t capable of handling the extra 2 A of filament current, you’re guaranteed to blow it. And replacing a power transformer can cost several hundred bucks once you factor in parts and labor.

So what can you do to tweak your power-tube tone if you’re not a tech? Get a bias meter and learn how to bias. Bias meters allow you to plug an ammeter (current meter) into the tube socket for an easy access measurement of the idle plate current. If you’re happy with the sound of your power tubes, measure their idle plate current and use that as a reference for biasing future power tubes of the same type or their direct substitutes. When biasing a new set of tubes, it’s always safer to start with the coldest bias-pot setting and slowly make it hotter while watching the current measurement increase on your bias meter. Don’t make the bias too hot, or your tubes’ plates will start glowing red and tube life will be cut short. Also, be sure you only play at a low volume with the bias meter in place so you don’t damage the meter. When in doubt, take it to a tech.

Beyond optimizing your amp’s biasing, you can also experiment with new sounds even with the existing tube types. Some manufacturers’ offer matched power-tubes sets (of two or four) that come with measurements based on how much plate current they draw at the same bias point. Hotter tubes will have a higher plate-current number, and the cooler tubes will have a lower plate-current number. And you can actually hear a significant difference in tone when a power tube is running hotter or cooler: When biased for the same amount of idle plate current, the hot tube will get louder, with less distortion, and the cooler tube will break up easier, allowing for more power-tube distortion. You should also try different brands of power tubes, because there are tonal differences.

One way to swap power-tube types without having to involve a tech is to try a converter like those from Yellow Jackets or VHT. (Full disclosure: My employer, AmplifiedParts.com, owns the Yellow Jackets line.) If your amp comes with one of the common octal power-tube types (6L6, EL34, 6V6, 6550, 7027, or 7591), these converters allow you to plug cathode-biased EL84s in their place without bias adjustment. This allows you to get more power-tube distortion at lower overall acoustic volumes, as well as give your amp some of that famous British EL84 flavor.

Finally, if you want to switch it up completely and try out a different power-tube type that is not considered a direct substitute for your amp’s original power tubes, contact the amp manufacturer or a technician first. It may be possible, but an expert needs to ascertain this based on the tube types and specific amplifier circuit in question.

Photo by Tom Moberly.

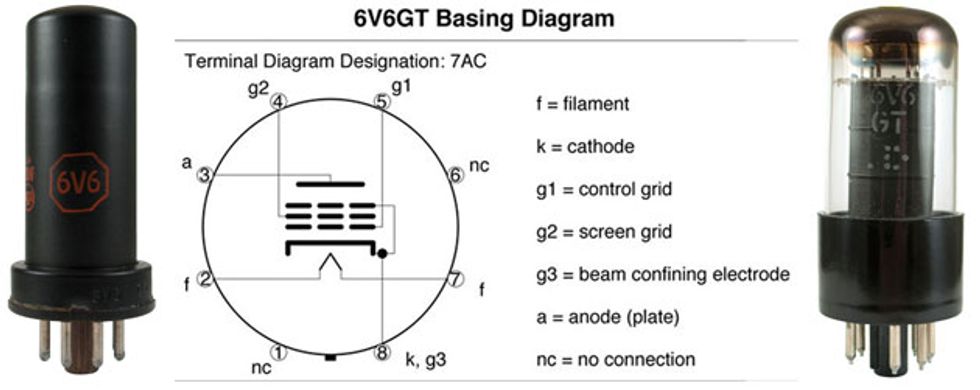

6V6GT

- NOS electrical specs (GE essential characteristics)

- Classification by construction: “beam power amplifier”

- Filament volts: 6.3 V

- Filament current: 0.45 A

- Max plate volts and watts: 350 V, 14 W

- Max screen volts and watts: 315 V, 2.2 W

1950s Fender Tweed Champ. Photo courtesy of Tim Mullally and Dave's Guitar Shop.

Like a small cousin of the 6L6, the 6V6 started out as a metal tube in the 1930s. Developments in the 1940s culminated in the glass 6V6GT we know today. Because the original metal 6V6 is no longer made, most guitarists simply refer to the 6V6GT as “6V6.” The 6V6GT is commonly associated with Fender student-model amps of the ’50s and ’60s, like the Princeton and Champ. Eric Clapton recorded “Layla” with Derek and the Dominos using a Champ.

1960s Fender Blackface Princeton—the 6V6GT has a more straightforward tone than the 6L6GC, with reduced low-end and a little less treble chime. Photo courtesy of Tim Mullally and Dave's Guitar Shop.

The 6V6GT has a more straightforward tone than the 6L6GC, with reduced low-end and a little less treble chime. It breaks up into overdrive more easily, and it can be useful for getting classic American tone with power tube distortion at relatively low levels.

Photo by Tom Moberly.

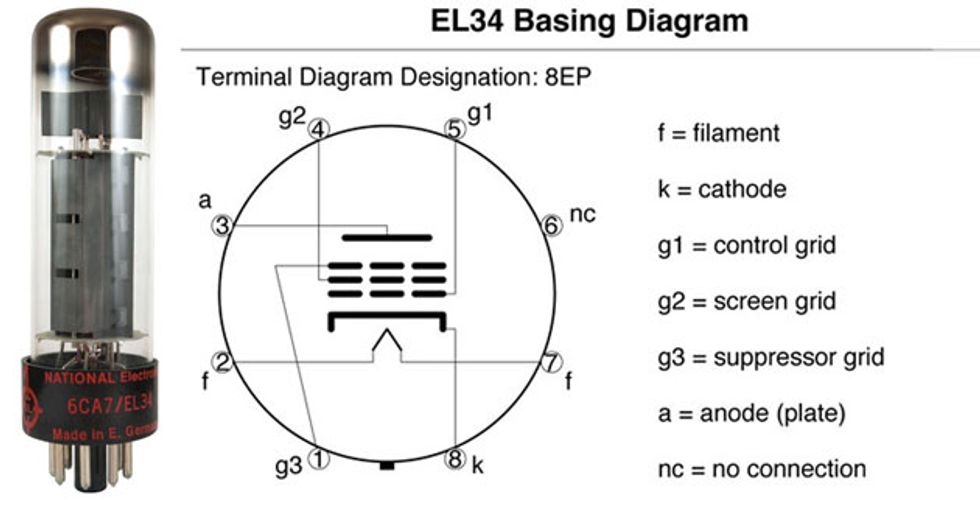

EL34

- NOS electrical specs (Philips Data Handbook)

- Classification by construction: “A.F. output pentode”)

- Filament volts: 6.3 V

- Filament current: 1.5 A

- Max plate volts and watts: 800 V, 25 W

- Max screen volts and watts: 500 V, 8 W

First introduced in the early 1950s in the Netherlands, the EL34 is commonly associated with the British sound of high-gain Marshall amps. In 1966 Marshall switched from the KT66 to the EL34 as their power tube of choice. In September of that year, Jimi Hendrix arrived in England to form the Jimi Hendrix Experience and, taking his cue from Pete Townshend of the Who, began cranking Marshall amps. The EL34’s low-end frequency response is leaner and possibly meaner than that of the 6L6GC. With tight mids and crisp highs, the EL34 is more easily overdriven than the 6L6GC, providing softer crunch distortion.

A 1959 Super Lead Plexi Serial #12237—with tight mids and crisp highs, the EL34 is more easily overdriven than the 6L6GC, providing softer crunch distortion. Photo courtesy of Marshall Amplification.

The 6CA7 and KT77 are common substitutes for the EL34. The 6CA7 is the American designation for EL34, and some 6CA7 versions use beam power construction instead of a true pentode. Try a 6CA7 in place of an EL34 for more pronounced low-end frequency response with a little more headroom.

The tonal differences between the KT77 and EL34 aren’t dramatic, but there is a significant structural difference: the KT77 doesn’t have an internal connection at pin one like the EL34 and 6CA7 do. This can make it easier to install KT77s in certain American amps designed for the 6L6GC, yielding a more British sound. Amp manufacturers would often use lug 1 of the tube socket for other circuit connections incompatible with an EL34. Could this be why the MOV (Marconi-Osram Valve Co.) datasheet designates the KT77 as having an “international octal” base? If not, at least it helps us remember that there is a difference between the pinouts of the EL34 and KT77.

Photo by Tom Moberly.

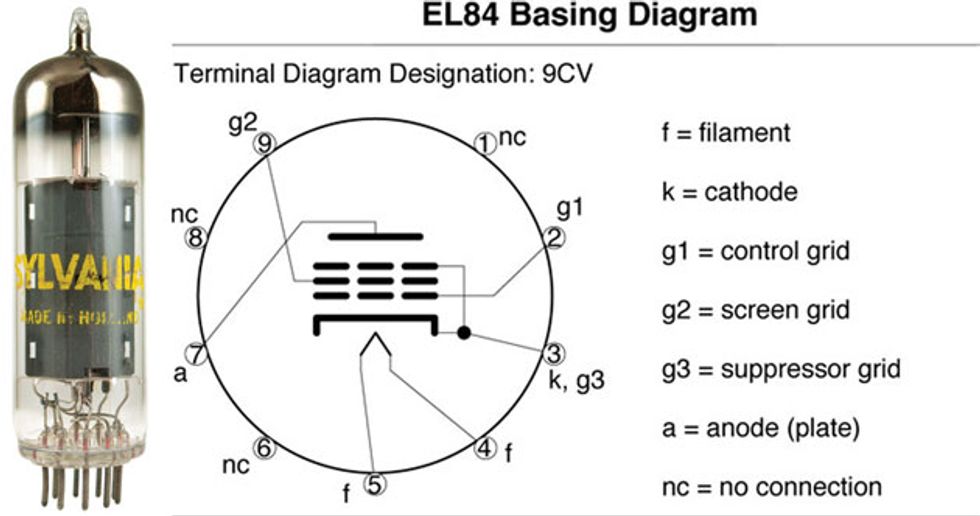

EL84

- NOS electrical specs (Philips Data Handbook)

- Classification by construction: “A.F. Output Pentode”

- Filament volts: 6.3 V

- Filament current: 0.76 A

- Max plate volts and watts: 300 V, 12 W

- Max screen volts and watts: 300 V, 2 W

Another early 1950s creation from the Netherlands, the EL84 was probably designed for affordability, and it helped make hi-fi stereo systems more accessible to the masses. The EL84 is commonly associated with the British sound of Vox amps. Its almost beam-like focus is bright and clear, with lots of top-end sparkle transitioning easily into tight overdrive distortion. The Beatles cut a deal with Vox in 1962, forever identifying the AC30 and its four EL84 power tubes with the early British Invasion sound.

A 1960s gray panel Vox AC30 Top Boost—the EL84 is commonly associated with the British sound of Vox amps. Its almost beam-like focus is bright and clear, with lots of top-end sparkle transitioning easily into tight overdrive distortion. Photo courtesy of Tim Mullally and Dave's Guitar Shop.

The American designation for the EL84 is 6BQ5. Some 6BQ5 versions use a beam power construction instead of a true pentode one. There is no significant tonal difference between the 6BQ5 and the EL84. Many brands are labeled with both American and European designations (i.e., 6BQ5/EL84).

Photo by Tom Moberly.

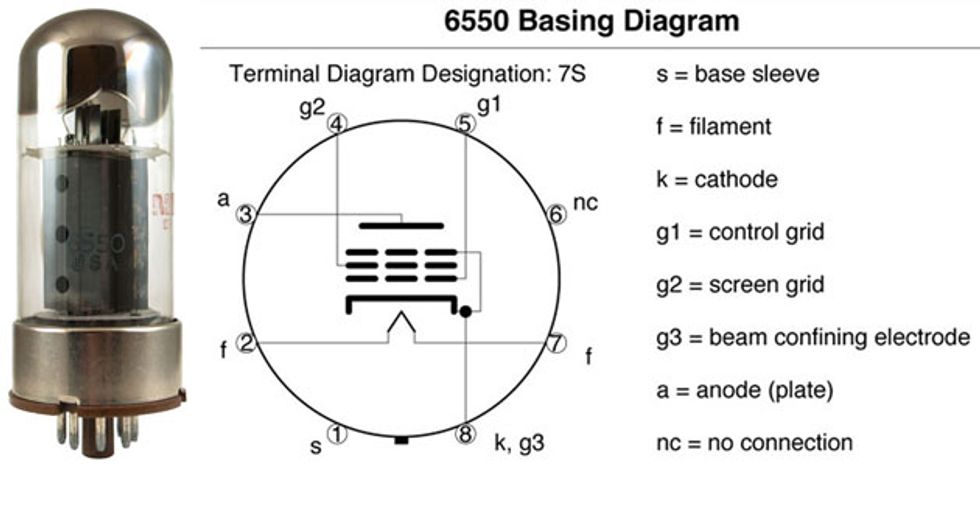

6550

- NOS electrical specs (RCA Receiving Tube Manual)

- Classification by construction: “beam power tube”

- Filament volts: 6.3 V

- Filament current: 1.6 A

- Max plate volts and watts: 600 V, 35 W

- Max screen volts and watts: 400 V, 6 W

Introduced in the mid 1950s and made in the United States, the 6550 met the demand in hi-fi audio for greater power and less distortion. Ampeg used six 6550s in their SVT (“Super Vacuum Tube”) amp in the early 1970s, creating an extremely clean, round, and warm sound that would become a classic for bass players.

The 6550 is not commonly used in guitar amps, but in the 1970s the US distributor for Marshall sold many JMP guitar amps with 6550s instead of EL34s. (Supposedly, many EL34s were faulty by the time they arrived in the US, and the distributor concluded that the rugged 6550 had a better chance of surviving the duration of the warranty.)

Ampeg used six 6550s in their SVT amp in the early 1970s, creating an extremely clean, round, and warm sound that would become a classic for bass players. Photo courtesy of Chicago Music Exchange.

The KT88 is a common substitute for the 6550. There’s not a dramatic difference in tone between the two types. Used with guitar, the two tube types sound tight, bright, and powerful, with a slight overdrive crunch and relatively little compression compared to other tubes. They could be useful for maintaining clean sounds at high volume, or keeping the emphasis on preamp distortion instead of power-amp distortion.

Tubes and Valves: Today and Tomorrow

These days manufacturers from all parts of the world design amps around both traditionally British “valves” and American “tubes,” recreating classic tones while meeting the demands of newer musical styles. Why are so many guitarists still crazy about tube amps? I think their ongoing popularity is largely due to a raw beauty and warmth of tone that’s hard to describe—but it feels so good!YouTube It

This 1963 clip of Dick Dale and the Del-Tones demonstrates the loud, articulate sound of the 6L6GC power tubes used in the era’s large Fender amps.

It’s widely assumed that Eric Clapton’s iconic performance of “Hideaway” with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers was played through a Marshall JTM with KT66 power tubes.

Buddy Holly’s Fender Bassman probably had 5881 tubes, as heard in this 1957 performance of “Peggy Sue” on Arthur Murray’s Dance Party.

Eric Clapton recorded “Layla” with Derek & the Dominoes using a 6V6GT-equipped Fender Champ.

While Jimi Hendrix often used Fender amps in the studio, his live sound blasted from Marshall amps likely powered by EL34 power tubes.

Check out the Beatles’ EL84-equipped Vox amps at this live Manchester, England, performance from 1963.

Steely Dan’s Walter Becker delivers a classic 6550-powered SVT sound on this 1973 Midnight Special performance of “Reelin’ in the Years.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)