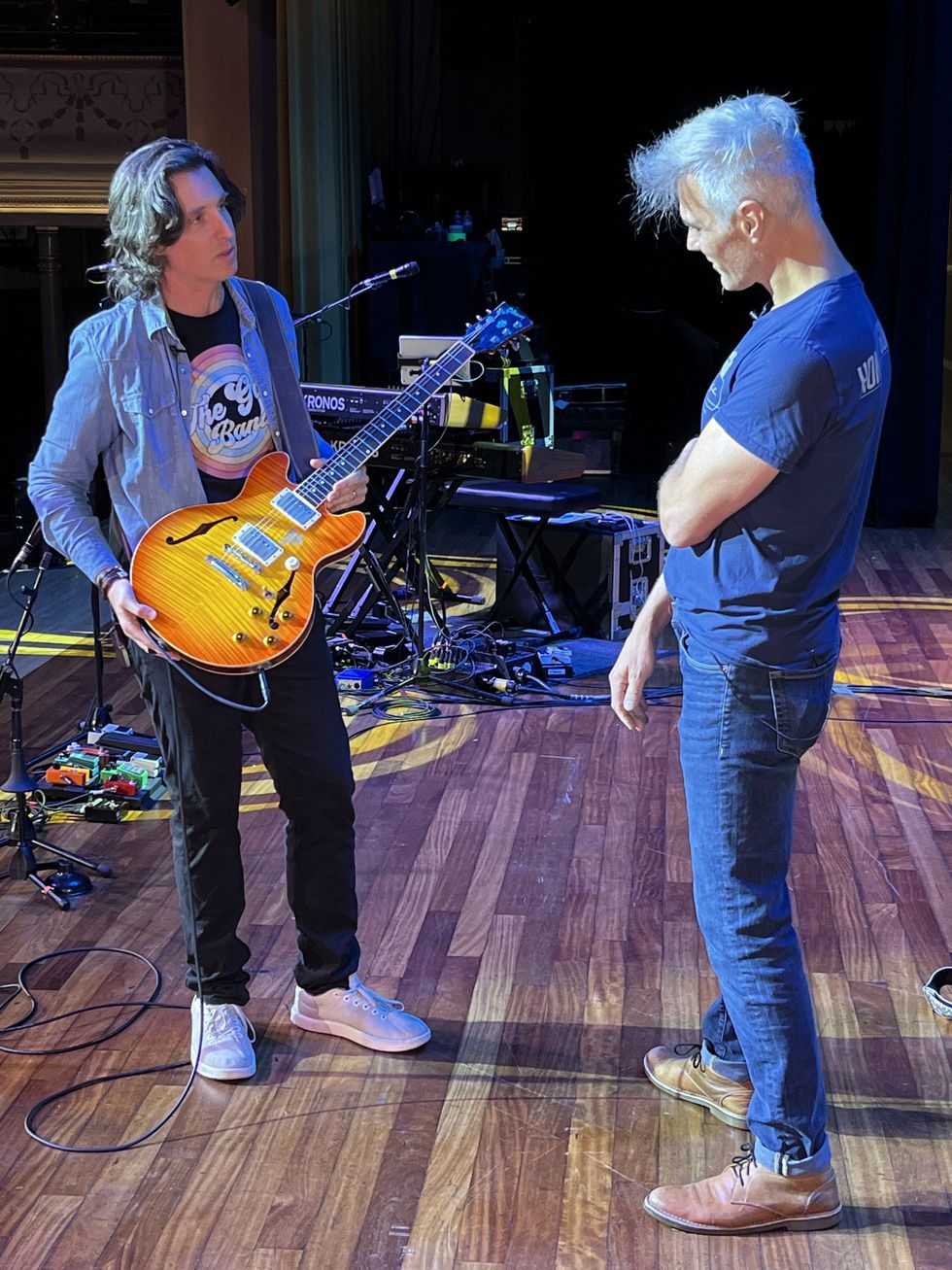

Little Feat’s Fred Tackett and Scott Sharrard take PG through their 2023 touring rigs.

Formed in 1969 by slide guitar juggernaut Lowell George, disbanded after his death in ’79, then revitalized in 1987, Little Feet combines George’s bandmate and co-writer Fred Tackett along with virtuoso Scott Sharrard in their new recording and touring lineup. Tackett and Sharrard invited PG’s John Bohlinger to their soundcheck at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium to talk gear and tell classic stories from Little Feet’s early days.

Brought to you by D'Addario XSRR Strings.

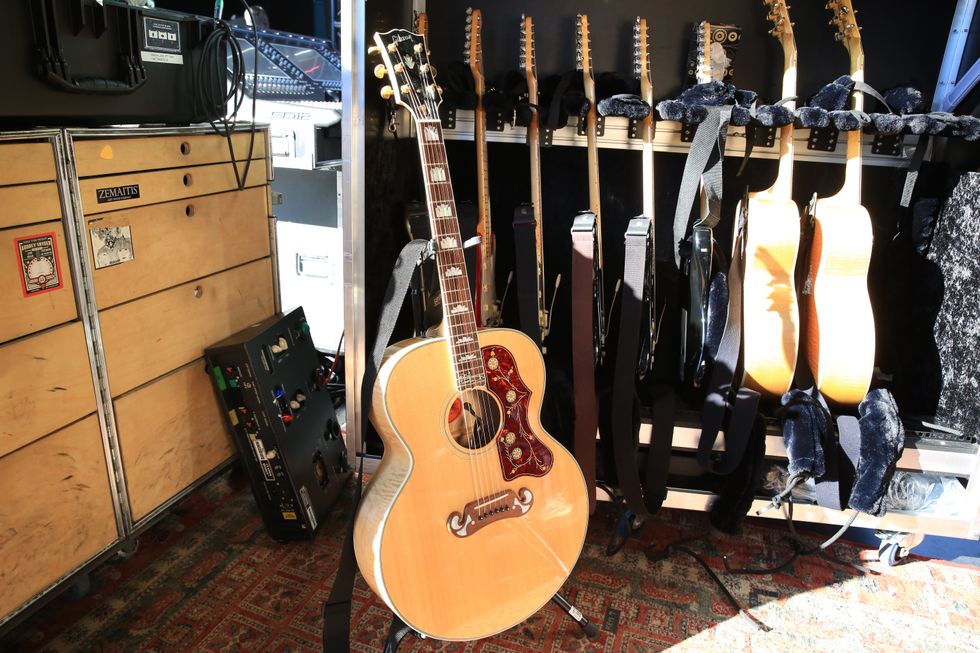

Fred Tacket's Gear:

Fred Tackett tours with two stock ’80s Stratocaster Ultras. The 1988 Sunburst, which features a rosewood board, is used for conventional playing.

Tackett’s maple neck 1984 Red Strat Ultra is set up higher for slide.

Tackett’s 1964 Fender Deluxe was modified years ago by Paul Rivera.

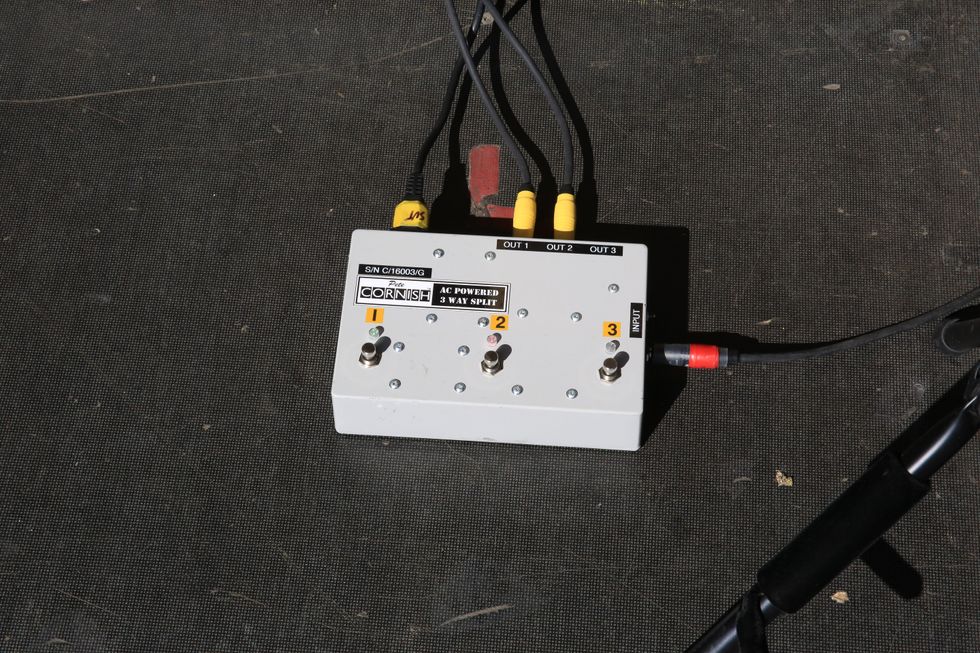

Tackett’s pedal board features a Boss TU-2 Tuner, Dunlop Cry Baby, JHS Pulp ’N Peel V3, Boss Tremolo TR-2, MXR Phase 90, Boss DD-5 Delay with Boss FS-5U tap, Ibanez TS9, and a tiny mystery M boost.

Scott Sharrard's Gear:

This Heritage H-137 features Lollar P-90 pickups and stays in standard tuning with StringJoy strings (.095-.046). Sharrard uses Magslide pinky-model slides and Jim Dunlop Primetone picks.

This Gibson CS-336 is Sharrard’s #1. It features Wizz pickups, as well as custom wiring and work by Paul Schwartz.

This custom Novo Serus T also sports Lollar pickups. It lives in open-G tuning with a heavier set of strings (.013-.056).

This 1988 Fender Strat Plus circa 1988 is Sharrard’s primary electric guitar. It’s got Lollar pickups, an Alembic Stratoblaster mid-boost switch (a la Lowell George), and currently lives in open-A tuning.

Sharrard tours with three amps, and runs either one or two depending on the size of the venue. On this show, he ran a Two Rock Classic Reverb 100/50-watt head with a 2x12 vertical closed back cabinet, loaded with Celestion Heritage G12-65 speakers

Sharrard’s second touring amp is his vintage 1966 Fender Vibrolux Reverb 2x10 combo amp, with Celestion G10 vintage speakers

Sharrard’s pedalboard contains a TC Electronic PolyTune, Analog Man Bi-CompROSSor, custom Klon made by Charlie Martinez, Strymon Lex Rotary Speaker Simulator, Strymon Flint, Radial Switchbone for when both amps are in use, a backup PCE-FX Aluminum Falcon, and Radial DI for acoustic guitar.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)