Karma—despite the John Lennon song—isn’t always instant, or as Mike Watt (Minutemen, Firehose, Stooges) says, paraphrasing Orson Welles, “No wine before its time.”

Some things take a while.

Watt’s most recent project, Big Walnuts Yonder, is a case in point. The ensemble—an alternative supergroup of sorts—features Watt on bass, Nick Reinhart (Tera Melos) and Nels Cline (Wilco) on guitars, and Greg Saunier (Deerhoof) on drums. The project was years in the making, from inception to realization, and given the busy touring and recording schedules of the parties involved, it’s amazing it ever came together at all.

But it did, and praise the heavens, what a joyful noise it is. From the faux James Brown guitar breaks of the album’s opener, to the free sounds of “Flare Star Phantom,” to Cline’s righteous Beatles’ Revolver-era solo at the end of “I Got Marty Feldman Eyes,” Big Walnuts Yonder is a feast for the ears. For pedal geeks, it’s even better. Reinhart and Cline had about 70 pedals between them, according to Watt. (On the other hand, he plugged straight into an amp.)

The project started with a conversation between Watt and Reinhart while on tour. “My band, Tera Melos, crossed paths with Watt and his band, the Missing Men, in Ireland,” Reinhart says. “We were playing a show together in Dublin and were hanging out backstage. Whenever you’re sitting around with Watt, you just have questions for the guy. He’s a legend. He told us Black Flag stories from the SST days. Hearing about the Minutemen and that whole world is really exciting for guys my age, in our mid-30s, who grew up on that stuff. I asked him about his record, Contemplating the Engine Room, which Nels plays on. I mentioned the song ‘The Boilerman’ because the guitar in that song is so ripping and crazy. I’d never heard guitar like that over that kind of music. I said, ‘Man that must have been crazy, Nels ripping over that.’ And Watt’s response was, ‘You want to know Nels? You’ve got to play with Nels.’ Then he said, ‘Let’s start a proj.’’’

Proj is Wattspeak for project. Other terms include booj for bourgeois, leash for cellphone, and spiel for story. “Watt created this band in front of our very eyes,” Reinhart continues. “He said, ‘You, me, Nels …’ He asked me to find a drummer. I just blurted out, ‘Greg Saunier from Deerhoof would be a really neat addition to that.’ He immediately agreed, emails were sent out, and it basically took—I’m fuzzy on the dates—but it took maybe two years to get everyone’s schedules lined up and for a recording date to be set.”

But the Cline-Saunier connection runs deeper than Reinhart imagined, Watt explains. “Nick said, ‘How about Greg Saunier from Deerhoof?’ Well, that’s a trip because maybe 17 years ago, the first time I saw Deerhoof, it was Nels Cline taking me and introducing me to Greg Saunier. See? It’s all about people. Like most stuff in the world, it’s people. To me, that’s the most genuine connection. Not genre, not names, not all this other stuff that’s kind of surface. It’s people.”

Big Walnuts Yonder was a collaborative effort, though Watt provided most of the material for the band’s eponymous album by circulating rough sketches of his compositions played on bass. “The plan was, I’ll write eight songs, Nels will bring in a song, and Greg will bring in a song,” Watt says. “Now, I’ve done this a bunch of times. Nels loves it because—springboards, launchpads—that’s what he looks at. A lot of people, you give them just the bass and they’re like, ‘What?’ It’s like writing it on cymbals or kick drum. But for Nels, there’s a little direction, but it doesn’t have all that harmonic content that maybe a piano or a guitar has. He digs it, big time.”

What follows is a discussion with Watt and Reinhart about the origins of this project, the gear they used to record Big Walnuts Yonder, über-geeky pedal talk, and a plethora of other fun and interesting nuggets. The interviews were conducted via phone and Skype. Watt was in Shaker Heights, Ohio, with his band, the Jom and Terry Show, finishing up a tour with Meat Puppets. Reinhart was in Northern California visiting family and preparing for an upcoming tour with Tera Melos.

TIDBIT: Watt provided most of the material for the band’s eponymous album by circulating rough sketches of his compositions played on bass. “A lot of people,” says Watt, “you give them just the bass and they’re like, ‘What?’ But for Nels, there’s a little direction, but it doesn’t have all that harmonic content that maybe a piano or a guitar has. He digs it, big time.”

Nick, the point of this project was to get you to play with Nels. What was that like?

Nick Reinhart: Incredible. I mean, that guy, he’s like a wizard. Mike had these compositions that he sent over my way. I sat there and listened to them. I was nervous, like, “What am I going to bring to the table with these three legendary dudes?” Legendary in my book and obviously in a lot of other people’s books, too. I hunkered down and really put all this mental energy into it—not knowing what Nels or Greg would bring to it—and I came up with these guitar parts.

Email chains in this band are so crazy, because these guys riff on each other. Watt will make an obscure reference to some obscure bass player that played on a jazz record in the ’70s. That would get these guys going and it revs up hard. The email chains got really, really long and convoluted. You’re basically deciphering what is happening in this email chain, which makes the communication in this band—for me—a little difficult. I’m like, “Wait. Where is this going right now? This is crazy.”

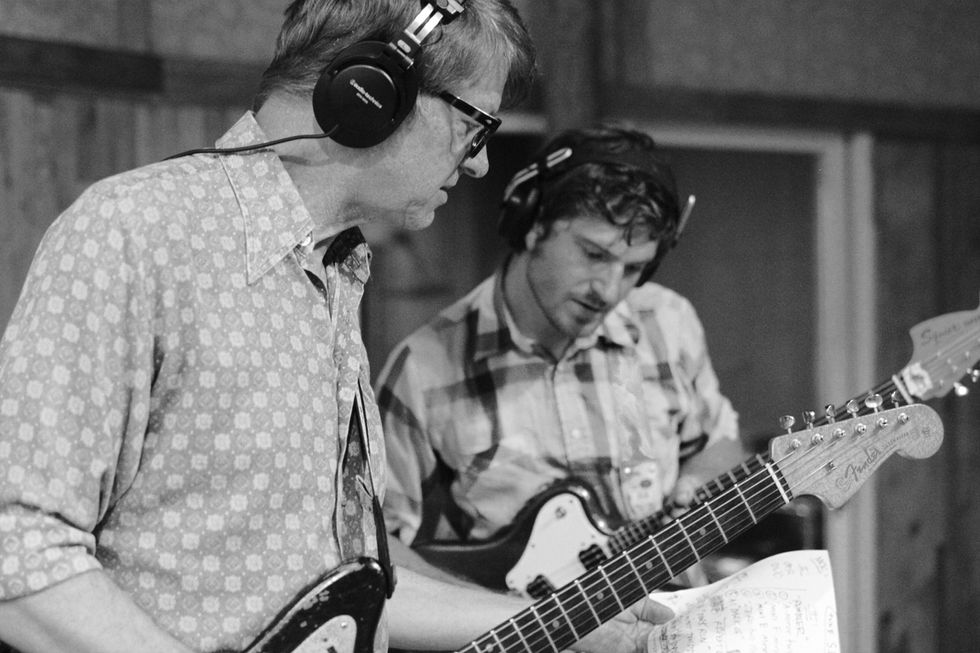

I didn’t know what was going to happen when we got into the studio. Watt and I had sent over these ideas, these compositions we had. But Greg and Nels are constantly on tour and I don’t know if they ever sat down with the material. I definitely know they checked it out, but I don’t know to what extent. When we got to the studio, Greg and Nels said, “Let’s pick one. You guys show us how it goes and we’ll jam it.” We would play together for 15 minutes and you could see the magic in Nels’ brain and hands working right before your very eyes. That was crazy. The stuff he would come up with was like, “Boom. That’s it.” Right there on the spot. It was incredible just seeing it appear that way.

For the Big Walnuts Yonder sessions, Mike Watt played a 1966 Fender Jazz bass owned by Tony Maimone, whose low-end lines powered Pere Ubu from the mid ’70s through the early ’90s. Photo by Lucas Hodge

What did Mike send you? Bass parts?

Reinhart: I need to be specific about this because it’s important to understand what this was. I know this sounds inconsequential, but you said, “bass parts.” I used that term at one point and I think Watt took issue with that. He calls them “springboards.” Yes, they are bass lines technically, but they’re songs. That’s why I’m saying “compositions.” Watt wrote A and B and C parts and structured these songs loosely. When we got in the studio, some things changed, but he had a concept of what he wanted the actual compositions to be.

Approaching Watt’s compositions was like, “There’s no one that plays bass like him.” There are really odd choices of notes and structures and patterns and stuff. It was a way I’d never written before, which was amazing. One of the points of this project was to do something new for each of us. For me, that’s why I’m saying I spent a lot of time with it. I wanted to add something unique and special to what Watt had created on his own. I sat with all this stuff and pulled melodies out of these weird, very Watt notes and Watt chord progressions and tried to put my own spin on it. Then the songs existed in bass and guitar form and Nels and Greg, like I said, came into the studio and added their magic to it.

Mike Watt: I wrote whole songs without the other parts. I know it’s funny because the context is: bass is glue. It’s what glues things together. I sent him the parts. Greg and Nels didn’t hear them. They didn’t want them. They wanted to be in the moment. But Nick Reinhart wanted them—he’s the young man, he’s the new guy, he’s feeling a little pressure. It’s like when I did that gig with Jandek with the young man from Health on drums [BJ Miller]. So I’ve flown in my eight. Nels was going to bring in his composition and Greg was going to bring in his composition the day of recording, which is the way I asked for them. That’s what I wanted to do—be in the moment a little bit, maybe 20 percent [laughs], because for 80 percent, I knew what was up.

But Nick Reinhart, he takes these things, and he develops guitar parts over my bass things. He comes to the recording—summer of 2014 in Brooklyn, I think in July, three days—he comes prepared. Now, he doesn’t know Nels’ tune. He doesn’t know Greg’s tune. He had to do a little 20-percent free flight, too. But he had all his stuff worked out. Now, it wasn’t set in stone. Once he started playing with Nels, which is the whole crux of the proj—it’s the dynamic of those two coming together.

Mike Watt’s Gear

Basses1966 Fender Jazz with EMG pickups and a Leo Quan Badass bridge, (borrowed from bassist/producer/engineer Tony Maimone)

Amps

Mini Ampeg SVT with a 2x10 cab (most likely the 100-watt Micro CL SVT Classic Stack) (borrowed from Tony Maimone)

Nick Reinhart’s Gear

GuitarsBlue sparkle Squier Super-Sonic

Amps

For this session, a Fender Princeton Reverb and a newer Vox combo, but typically a Peavey 6505 combo in parallel with a Roland JC-120 or smaller JC-40.

Effects

Boss DD-5

Boss PS-5

Boss TU-2

Line 6 DL4

Line 6 FM4

DigiTech XP-200 (with Space Station XP-300 mod)

Dwarfcraft Devices custom “Reinhart” (Great Destroyer plus Hax)

EarthQuaker Devices Bit Commander

EarthQuaker Devices Palisades

EarthQuaker Devices Rainbow Machine

Ibanez FZ7

Ibanez Modulation Delay III

Mantic Proverb

A furry green fuzz borrowed from Nels Cline

Strings and Picks

.010–.046 set (any brand)

1.0 mm (any brand, but usually blue)

And I’ll tell you, in D. Boon’s days—we were boys in the early ’70s—you would never imagine playing with a guy 30 years older than you. [Editor’s note: D. Boon was the guitarist in the Minutemen, and you’ll find his Forgotten Heroes profile here.] That shows you how much more open-minded things are these days. I know everybody’s talking about the bad new days, but there’s some real good things. They used to use age for marketing this kind of music, but I guess when you have 70-year-old Rolling Stones you can’t be … [laughs] … it becomes music again. That’s a real good thing that came out of the punk movement, I think. This thing of taking down age, or where you’re from, or genre, or all those barriers that really, as far as music, in my opinion, are kind of phony. When it gets down to it, it’s people playing together.

It’s much more egalitarian that way.

Watt: Right. I mean, we use these words. They’re not just for the bumper sticker. Let’s live them.

Nick, you and Nels both use a lot of pedals. Did you work together to craft textures or was it more reactive?

Reinhart: It was song-by-song. There were times where Nels was like, “Nick’s doing that, I can react this way with this sound.” We both had massive pedalboards in there. What’s really fun is that Watt was going direct into his amp. I don’t even think he had a tuner out front. But that was also Watt’s concept from the beginning: Nick and Nels shredding side-by-side and bringing these two brains together and see what happens. There’s a lot of reactive stuff between the two of us, on my end, too.

Watt: I didn’t use pedals. They used pedals. Look, with Nels it’s a dance. I learned this a long time ago. But do you know what’s the funniest thing about Nels? His favorite pedal is volume. That’s what he told me. It was funny to watch them both because Nick had like 35 pedals and Nels had like 35 or 40 pedals. To see these dudes do the dance facing each other working the neck … I sit down when I record and there I’m witnessing this. And then on the side there’s Greg Saunier. You know, he only uses kick, snare, and like 20-inch high-hats—he’s a unique drummer. And to see this, it was sort of like being in front of the Stooges. You know all this music and you’re part of it, yet in a weird way you’re witnessing this. It was a real trip.

Why do you sit down in the studio?

Watt: I use long scales when I record, so that’s why I sit down. But I’ve got to use little ones [short-scale basses] when I play live. Hey, I’m less young now, you know. Gotta work the room.

What bass did you use for these sessions?

Watt: Tony Maimone’s 1966 Fender Jazz with EMG pickups and a Badass bridge. [Editor’s note: Tony Maimone, the session’s engineer, was the bass player in Pere Ubu.] And the amp was like a minute version of the SVT. I think it has two 10s—they make a little toy version. It’s tiny. It looks just like the real thing. So that’s all I used. No pedals.

And that was it? Did you have a line direct to the board as well?

Watt: It was mic and line. And you know, you’ve got a bass man recording you [laughs]. One of your heroes. Me and D. Boon saw Pere Ubu do The Modern Dance in Hollywood at the Whiskey in ’77. It blew our minds. I mean, it was like, “Whoa.” I’ve become friends with this man, and he’s had a studio since the ’80s called Studio G, now in Brooklyn. He let me use his bass and he recorded it. It’s all about people.

I’ve really gotten to the point where I’m not into genre any more. Music is music. I think that’s the only way for me to stay a student and keep my mind open. Otherwise, it’s some kind of weird prison system. I don’t want that in my head with music. Music is too righteous.

Both Cline and Reinhart are masters of spontaneous signal processing. “We would play together for 15 minutes and you could see the magic in Nels’ brain and hands working right before your very eyes,” says Reinhart.

Photo by Lucas Hodge

Nick, what’s your approach to pedals? Do you have certain sounds in mind that you’re going for or do you press buttons, see what happens, and then work off that?

Reinhart: Specifically, with this band, there were no pedals at first for me. It was truly just wanting to understand Watt’s perspective. Writing music to Watt playing bass is very different from just listening to it and enjoying it. There are all these little nuances in Watt’s writing, it was much simpler for me to figure it out with no pedals. Once I had those loose structures, then I could think, “Alright, I can relax a bit here. I can build a board and get certain sounds for here or there.” But then a lot of things were spontaneous in the studio. Like I said, I was reacting to what Nels was doing. So for this particular project, yeah, most of the composing was dry. But that changes for me from project to project.

Do you practice with pedals? Do you spend time refining your timing and exploring sounds?

Reinhart: Yes. I always like to have boards set up. To me, there is such an art to putting, say, a 30-pedal board together. There are so many different variables and important things that need to happen for it to be a functioning, fun, inspiring instrument to play. Because a pedalboard, in itself, for me, is a completely separate instrument.

At home, I always like having something set up that I can plug in and fart around on. That evolves. My band, Tera Melos, heads out on tour in June, so I’ve had this board set up for probably the last three weeks for this exact reason—being able to practice with a pedalboard and think, “These two need to come on at the same time. They’re far away from each other, but if this one were maybe on the bottom row, then I could double tap them with two feet somehow. How would I do that?”

What are your rules for setting up a pedalboard?

Reinhart: Anything that turns my guitar into another instrument—like a synth or lower-octave stuff—will go at the beginning, because I want to be able to then effect this new instrument. If I have drives or choruses or delays before this “new instrument” then that’s not going to make sense or translate correctly. So all of the “new instrument” sounds go at the very beginning. After that it’s generally modulation, pitch-shifting stuff, Whammys, and all of that. Then it goes into the delay/reverb world. Drive is at the end and there’s a looper at the very end. That’s my general signal path. It’s funny, I know I just recited that semi well, but often when I do a new board, I’ll pull up photos or notes. “Wait? Where is this? I remember liking this on tour.”

Nick Reinhart’s work area. Reinhart borrowed the furry green fuzz box from Nels Cline. “A pedalboard, in itself, for me, is a completely separate instrument,” Reinhart says. Photo by Nick Reinhart

The recording sessions took place in 2014. What took so long for the record to come out?

Watt: Well, Nick had to get all his singing on there. We didn’t know this. Nick Reinhart—the young man, the student—he kept us all in student mode. Because he goes home and starts singing over these things. We thought it was going to be an instrumental record. I gave him titles like “Tune R,” “Tune S,” “Tune T,” “Tune U”—just numbering them. I didn’t want them to have titles until they were realized. Nick goes, “Watt, why don’t you sing on ‘Tune T’ and ‘Tune U?’” “Well, sing what?” “Come up with some words.” I didn’t know it, but he’d done this for all the other ones. Except Nels’ tune [“Flare Star Phantom”], that one he left.

And also mixing. We really wanted Greg to mix it, but he had all this touring and stuff, so it had to wait. But Nick got all his singing on there. I got my singing. Greg took a couple of months to do it. The problem is, this is a proj, everybody’s got other musical lives going. Not to belittle the proj, but it’s a parallel universe.

Were you sitting in the same room during the sessions? Could you see each other?

Reinhart: This was full on, live, in the room. And that sounds crazy to have to make that point, but obviously now with recording and the way people do things, that’s a little more rare. I hadn’t done that since I was like 16, in a punk band, playing crappy punk-rock songs. There are songs on the record, like “Rapid Driver Moon Inhaler,” which is a fast, crazy song. The demo that Watt and I worked on was much slower. I’d even been rehearsing that song myself at maybe three-quarters of the speed of what it is on the actual record. That one I did add pedal work to. There’s a lot of sampling that happens in that song and a bunch of other wacky things. After I’d developed what my structure was going to be, I started adding in the fun sounds and all that. When we got to the studio and started jamming it, someone said, “Let’s speed this one up a little bit.” I was like, “Oh shit, here we go, this is crazy right now.” And then it was ripping a couple takes of it and that’s it.

YouTube It

Shot during the sessions that yielded Big Walnuts Yonder, this video reveals the chaos and beauty of Mike Watt, Nels Cline, Nick Reinhart, and Greg Saunier engaging musically.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)