Welcome to a two-part feature in Premier Guitar that will give the uninitiated all the basics needed to help them launch their quest for tubehead status. We'll also provide plenty of under-the-hood details to further bolster the knowledge of players who are already in the know about these glorious audio devices. I'll discuss preamp tubes this issue and output (power) tubes next issue, but before diving in, let's take a brief look at how tubes perform their sonic magic in the first place.

Once upon a time, vacuum tubes were used all over the place. They glowed their little hearts out in our television sets, car and home radios, hi-fi systems, and guitar amplifiers, and were crucial components in myriad military applications, from radar technology to missile guidance systems and more. Bit by bit they have been replaced in all of these functions by other forms of more compact and more stable technology… except in guitar amps, where they maintain their preeminence over all kinds of far more advanced electronics. Is this just nostalgia, or mere perversity on the part of guitarists? Not in the least: when used to amplify electric guitars, tubes still simply sound better than anything else out there. Sure, there are some respectable sounding solid-state amps, and digital modeling amps have also made inroads into the market, but ninety-nine out of a hundred serious pros (if not more) continue to use tube amps for both recording and touring, and these little glowing bottles still define the cornerstone tones of rock, blues, and country guitar.

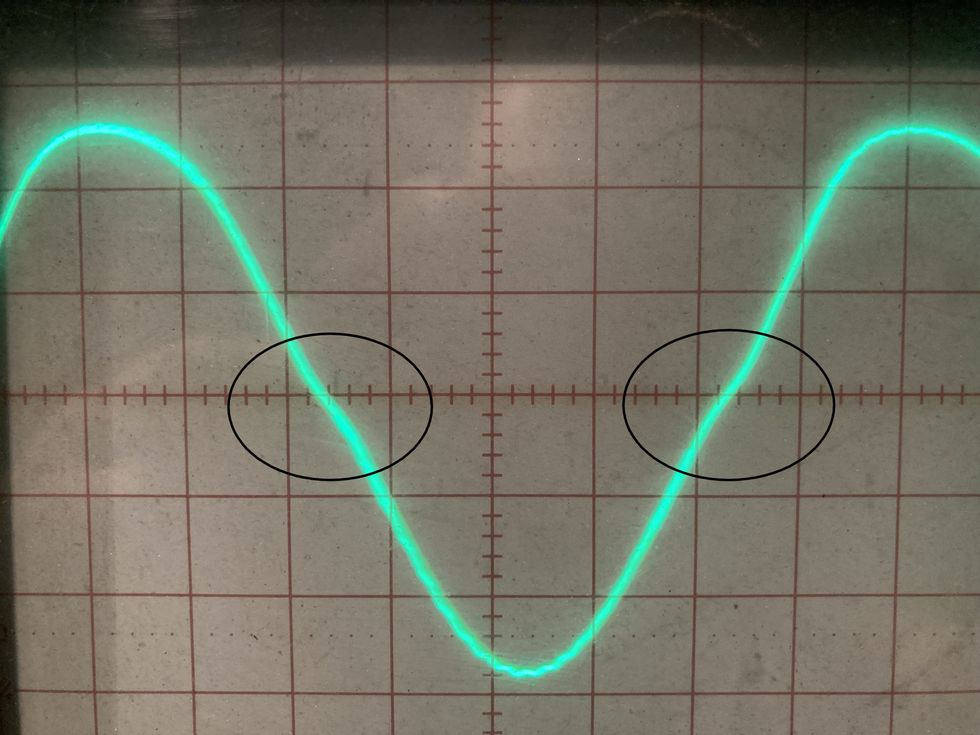

To get quickly to the heart of tube magic, stop thinking of them as amplification devices and start thinking of them as tone-generating devices. A tube-based amp makes your guitar louder, sure, but tubes amplify your electric guitar so beautifully mainly because of the way they distort. To put it as briefly and concisely as possible: push a simple transistor circuit hard, and it clips (distorts) in a sudden, harsh, "square wave" way; push a tube into clipping and it distorts more gradually and more smoothly—it "rounds off" into distortion—and slathers on a gorgeous gravy of harmonics along the way. There are a lot of other factors involved, of course, but that gets us to the nut of it.

This is why any decent sounding solid-state amp requires a lot of extra circuitry to do what a very simple tube amp circuit can do naturally. And be aware, too, that when I'm talking about distortion, I'm also referring to sonic elements that influence your so-called "clean tone." Most tube amps, even when set to clean levels (unless you've got the volume of a powerful amp set extremely low) are still distorting a little, and that distortion creates layers of harmonic depth that sweetens and fattens up that thing that we call our tone, even when we're playing "clean."

All amplification tubes carry at least four elements within their vacuum-sealed glass bottles: a cathode, a grid, a plate (also called "anode"), and a filament (or "heater"). The most basic tubes are called "triodes," named for the first three of these elements (a filament is always present, so it's ignored in the naming process). Pentode tubes, which account for most output tubes and a few preamp tubes, carry two further grids—a screen grid and a suppressor grid—that help to overcome capacitance between the control grid and the plate.

In simple terms, a tube's job is to make a small voltage (guitar signal) into a bigger one. How do they do this? Pluck a string on your guitar and the pickup sends a small voltage to the input of your amplifier, where it is passed along to the grid of the first preamp tube (think of it as the "input" of this tube). The increase in voltage at the grid causes electrons to boil off of the cathode and onto the plate at a correspondingly increased rate and, voila, the sound gets bigger. This slightly bigger signal from the preamp is passed along to the output stage, where the output tubes make it even bigger, to carry it on to the speaker via the output transformer.

(Note: some people refer to the latter as "power tubes", but I prefer "output" tubes because that better defines their function, whereas "power" might be confused with the power stage within the amp, AC/DC voltage conversion, and the work done by rectifier tubes, which is a different function altogether.)

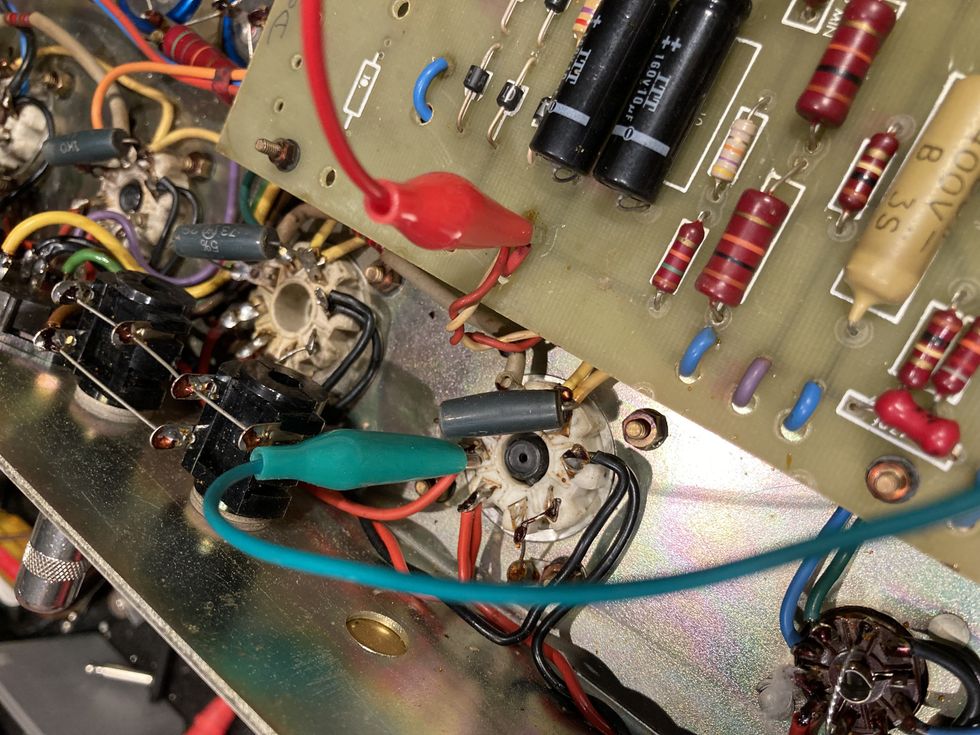

Preamp tubes and output tubes do essentially the same thing, just with varying degrees of bigness, if you will. Tubes are literally the amplifiers at the heart of your amplifier: they do the real amplification work, and everything else inside the box is there to help them run efficiently and to help pass along the signal. Of course, in addition to early amplification duties, preamp tubes are also used for other functions within the amp: to drive reverb or tremolo stages, for example, or to split the signal and reverse the phases of the two legs that are fed to the output tubes.

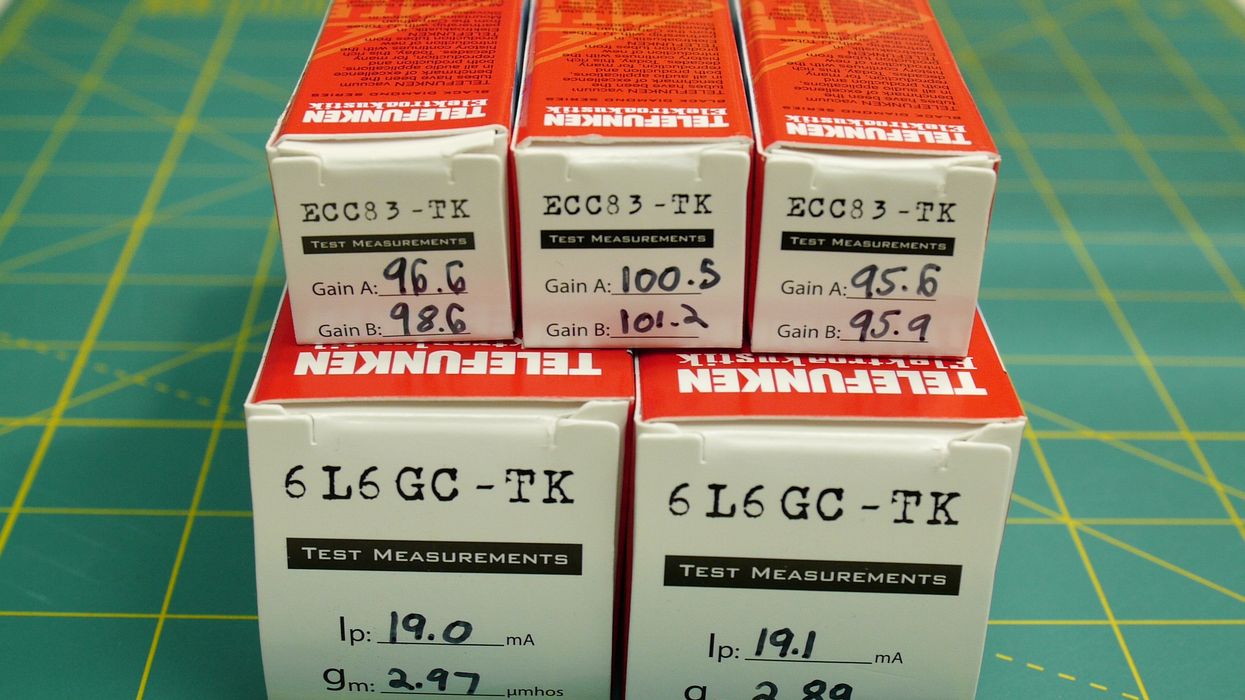

Preamp tubes are easily identified, in most cases, as the smaller bottles in your amp, and are usually positioned to correspond to your amp's inputs and early gain and tone stages. Sometimes they are covered with metal shields, which are easily removed. Since the mid-fifites, preamp tubes have mostly been of the smaller ninepin variety, although some older amps will still have bigger eight-pin (or "octal") tubes that fit the same sockets used by many types of output tubes. The most common type by far is the 12AX7 (also known by the designation ECC83 in Europe, or the high-grade US alternative 7025).

Some other types you will occasionally see look much the same, other than the numbers printed on them. These are: the 12AT7, often used in reverb-driver and phase-inverter stages; the 12AY7, original equipment in the first gain stages of many legendary Fender tweed amps of the mid and late fifties; and the 5751, a lower-gain replacement for the 12AX7. All of these are what we call "dual triode" types, because they contain two independent tubes within the same bottle. They are mostly differentiated by their gain factor— the degree with which they increase the signal they are given. The 12AX7 has the most gain of the bunch, and the 12AY7 and 5751 are direct substitutes with less gain, which in many cases means they'll distort the early stages of the amp less. The 12AT7 also has less gain than the "AX," but requires a slightly different bias voltage for optimal operation (it can be directly substituted in a pinch).

The only pentode preamp tube seen with any regularity in amps today is the EF86 (or 6267), which appeared in early Vox amps and has more recently been used in models from Matchless, Dr Z, 65amps, and a few others. Another less frequently seen, but much admired, pentode preamp tube is the 5879, notably used in Gibson's GA-40 Les Paul amp of the late fifties. Both of these pentodes fit the same 9-pin bottle as the dual triodes but require very different circuitry, and are known for their thick, robust sound. Both have higher gain factors than even a 12AX7, but aren't prone to distorting the way that dual-triodes can, and instead pass their fattened-up signal on to the next stage. They also have a reputation for handling effects pedals very well. Drive a 12AX7 hard, however, and it will induce quite a bit of sizzling, slightly fizzy-voiced distortion of its own. This can be a great thing if you're looking for a super-fried overdrive tone that's cooking at all stages, but not at all desired if you want more headroom and clarity, or the fatter distortion that's generated in the output stage of the amp when a cleaner preamp signal is driven into clipping at the output tubes (more of which in the next installment).

Some modern high-gain amps are designed specifically to create extreme yet controllable preamp tube distortion by cascading multiple gain stages, one into the other, with gain and master volume controls between them to control the drive levels at each stage. Used in this way, preamp tubes can produce a scorching, harmonically saturated lead tone that sustains all day—what we usually hear as a classic shred or contemporary rock tone—in an amp that really relies on its output tubes just to amplify this sound, rather than to add further distortion to it. When driven into distortion in a simpler, more basic amp with fewer gain stages (a category that might nevertheless include some very high-end, "boutique" tube amps), preamp tube distortion becomes just a part of the amp's overall distortion character, blended with clipping at the phase inverter and output stages, and often at the speaker too.

Counter-intuitive though it might sound, armed with the above knowledge regarding preamp tube distortion, many players have learned to create a bigger tone by using lower gain preamp tubes. To lower the gain of a preamp stage a little, you can swap a 5751 into any socket that carries a 12AX7. To lower it even more but retain the same performance characteristics (other than gain) you can use a 12AY7. Many players think the last thing they want to do is lower the gain of a preamp stage, but in doing so you can often prevent your signal from dirtying up in the preamp, and thereby pass a beefy, full-frequencied signal along to the output stage when the amp is cranked. This generates more output tube distortion, which results in a fatter, fuller tone in many simpler tube amps. This tip doesn't usually apply to high-gain type tube amps, whose whole raison d'etre is to generate preamp distortion. This 5751 swap is a trick that was used by Stevie Ray Vaughan, for one, to help generate his signature tone, and it has also been employed by plenty of other great blues players. If you're trying distortion and more output-tube distortion, you can also try using a 5751 in the phase inverter position, which is usually the last preamp tube before the output tubes.

Note: the term NOS, which stands for "new old stock", is applied to tubes manufactured many years ago but never put into use.

Even tubes of exactly the same type can sound quite different, depending upon their manufacturer and small changes in their design and production. The fact that tubes distort so organically also means that no two tubes distort or even amplify exactly alike. For one thing, while tubes are manufactured under fairly rigorous conditions, they are still imperfect devices. Every little fluctuation in assembly or materials results in a slightly different sound and performance from each tube that comes along.

That's why good tube distributors need to routinely test tubes they sell: put even two high-quality NOS preamp tubes from highly respected American or British manufacturers on a tube tester—say, a pair each of Mullard or RCA 12AX7 preamp tubes that came out of the factory on the same day in 1963—and they will most likely have slightly different readings for gain and other factors. Put enough of them up on a tube tester and some will even fail to meet required minimum standards. That's the way it is. Aside from giving different readings, these tubes will each sound just a little different, and other makes, both NOS and current, will sound different again.

What does this mean for the guitarist? For one thing, it behooves you to get your hands on as many different makes and types of tubes as you can reasonably afford. Try swapping a few around to see which ones help you to best achieve the tone you are seeking. The first preamp tube position usually affects the tone of that part of the amp the most (read your amp's tube chart or owner's manual to make sure you know how to change tubes safely, and are changing the right tube, and please don't touch any hot tubes! Let them cool down first). Try three different makes of 12AX7 or their equivalent in that position, and I'm willing to bet you'll notice a slightly different voice from each. Search the internet and read up on what other players consider to be the best current- manufacture tubes coming out today (there's too much detail on that subject to go into here). Also, see if you can find any affordable NOS tubes, or perhaps you can pull some used but functioning examples from old junker radio or hi-fi systems that you find at garage sales and swap meets. Experiment a little, and see which ones work for you. Preamp tube tasting can become addictive, and it's also a great way to fine-tune your tone.

[Updated 9/1/21]