There's no getting around it these days: If you want to gig with your acoustic, sooner or later you're going to need to plug in—and long gone are the days when a good instrument mic and a small PA system will suffice. Now you've got competition from the coffee grinder, espresso machine, blender, the cell phones, portable video-game systems, laptops, and any other stupidly noisy electronic devices a person can carry with them.

The only way you're going to make your trusty flattop(s) conquer the cacophony of the digital age is to arm yourself with some equally stellar guitar technologies—and a little acoustic amplification know-how. To that end, we've put together this handy guide with all the gear and real-worldapplication knowledge you need to make your gigs as easy and trouble-free as possible—whether they're on a street corner, in a coffee shop, or at a big outdoor extravaganza.

Pickups

When you're assembling an acoustic rig, you're putting together all the stuff that makes you sound like you. And to break down the process of getting your sound waves into electrified form, let's start with the question of how to get your lovely guitar's signal into wires that can then send it on to units that allow you to shape the tone, add effects, and ultimately amplify the glorious sound.

Many guitars currently in production are called "stage-ready," meaning they have electronics built in. Some of these guitars are remarkably good, but be sure you plug them in before you buy: The fact that a guitar sounds great acoustically doesn't mean its pickup—think of it as basically a microphone that captures the acoustic sound—will do it justice. The reverse is also true: Some guitars sound great plugged in but only sound so-so unplugged.

When you start to shop around for (or read about) acoustic pickups, it can seem as though there are as many on the market as there are guitars. One important consideration to keep in mind is that there are several different types of pickups, each with different pros and cons.

Passive vs. Active

Passive pickups are those that don't require any electronics to alter the sound (for example, by adding bass frequencies) before sending it to an amplifier or PA system. Of all pickup types, passives are the most analogous to a simple microphone—they pick up the signal and pass it through a cable to your guitar amp or direct-insert (DI) box (more on those later). Most electric guitar pickups are passive.

Active pickups require battery power, and have a certain amount of gain (essentially, the ability to boost volume) built in. If you have an acoustic that has a control panel (also called a preamp) on its side— typical controls would be volume, toneshaping EQ knobs or sliders, anti-feedback controls, and perhaps a tuner—then chances are it is also equipped with active pickups. (Some guitars also offer a tiny soundhole-mounted preamp with controls you access with your fingertips.)

If your acoustic doesn't have a pickup but you really want to use it for your foray into amplification, almost any pickup or pickup system you decide to use is going to require some sort of modification that you'll probably want a trained professional at your local guitar shop to handle. That said, there are some very good options that require little to no permanent mods.

Magnetic and Soundhole Pickups

Soundhole pickups are some of the most common— and easy-to-install—pickup options out there. These units simply slide into your guitar's soundhole, though typically you do need to have your end-pin (the strap button on the fat end of your guitar) drilled out to accommodate a 1/4" jack for the instrument cable. Despite the simplicity of this pickup type, there are some fantastically good models to choose from. There are both passive and active models, and they tend to cost between $150 and $300. Check out these models: DiMarzio The Angel ($159, dimarzio.com), Shadow SH 145 Prestige Active ($188 street, shadow-elecronics.com), L.R. Baggs M80 ($250 street, lrbaggs.com), Fishman Blackstack ($250 street, fishman.com), Seymour Duncan Mag Mic ($229 street, seymourduncan.com).

Contact Pickups

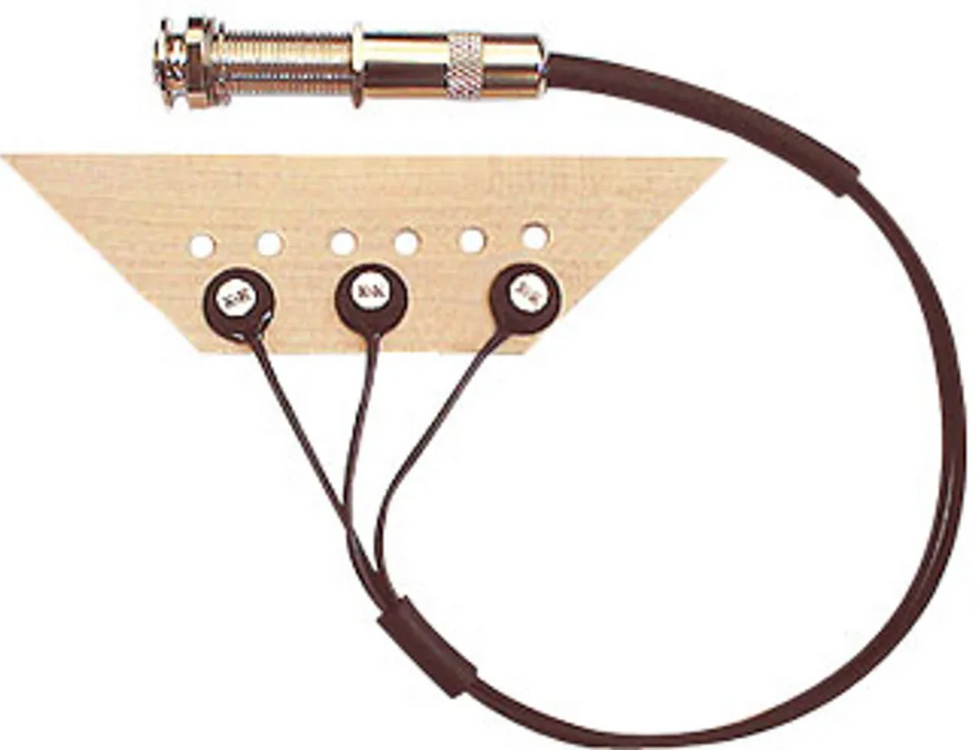

Perhaps the least invasive pickups at your disposal are contact pickups (aka "bottlecaps"), small, passive units that adhere to the top of your guitar with a sticky tack material that won't harm your axe's finish—and that comes off easily. No muss, no fuss. These pickups tend to be very microphonic, meaning they are more prone to generating annoying, high-pitched feedback at high volumes. For players who only perform once in a while at lower-volume gigs, these can work really well. Just be sure you try them on your guitar before you buy. Some can be rather thin and brittle sounding, so watch for that when you're auditioning them.

Another class of contact pickup mounts inside the guitar with glue under the bridgeplate (the dark piece of wood surrounding the area where the strings are anchored to your guitar's body). One of the best known is the K&K Sound Pure Mini ($91 street, kksound.com). This passive system sounds terrific, creates very little feedback, and, if installed properly, provides virtually trouble-free use. Here are some others to try: Pick-up the World PUTW #27 ($150, pickuptheworld.com), Schertler DYN-G ($608 street, schertler.com), LR Baggs iBeam (passive/$90 street, active/$140 street), B-Band Acoustic Soundboard Transducer ($75 street, b-band.com).

Undersaddle Piezo Transducers

If you've ever seen an acoustic guitar that had one of the aforementioned built-in preamps (the control panel mounted on the upper side), you may have wondered how the heck the sound gets from the strings and into that preamp. Most guitars like this have either a passive or an active undersaddle transducer—an "invisible" pickup that is installed under the white piece of bone or plastic (aka the saddle) in your bridgeplate. Undersaddle transducers are typically made of strips of tiny piezo crystals that sense vibrations and transform them into an electrical signal.

If you have an acoustic that sounds great, having an undersaddle transducer installed may be a worthwhile part of getting a satisfactory amplified tone. The procedure—which should be performed by a qualified professional— requires drilling a tiny hole for the pickup wire to pass through, as well as end-pin-jack installation. Some more affordable options (especially those that come in entry-level guitars) are prone to what guitarists often refer to as piezo quack—an artificial-sounding tonal artifact that often makes the guitar sound thin, annoying, and not very acoustic-like. Undersaddle piezo transducers are frequently paired with other types of pickups or microphones (see the "Multi-Source Systems" section below) for a richer, more natural sound and more versatility. Examples to try: B-Band Undersaddle Transducer ($43 street), D-TAR Undersaddle Series ($80-$115 street, d-tar.com), L.R. Baggs Element Active System ($129 street), Fishman AG Series ($90 street), Fishman Matrix Infinity ($150 street).

Internal Mics

High-end guitars sometimes come with preamps that incorporate a microphone mounted inside the guitar's body to capture a more natural acoustic sound. Internal mics usually work best in concert halls and places where you don't need to get really loud. If the volume gets too high, they will feed back in a manner that's unpleasant, distracting, and even painful. That said, the sound quality of internal mics can be extraordinary. If you decide to explore mics, be prepared to spend a few hundred dollars for both the equipment and the installation. We advise getting the highest quality and most feedback resistance possible, and consider a multi-source system for situations where your mic alone is problematic. Here are three examples in varying price ranges: B-Band Condenser Microphone ($75 street), Highlander Internal Mic ($175 street, highlanderpickups.com), Miniflex 2Mic ($490 direct, miniflexmic.com).

Multi-Source Systems

Multi-source systems are setups that combine two or more pickup types and control them via a single preamp. For versatility and sound quality, they're hard to beat, because different pickup types respond to and transmit your guitar's frequencies differently. For example, piezo undersaddle transducers provide a lot of articulation, definition, and feedback-free volume, while microphones do a better job of capturing the warm bass and midrange frequencies that make your acoustic sound airy and, well, acoustic. Blending the two typically requires using either an onboard or an external preamp (see the "Preamps and DI Boxes" section below for more on these), but it also usually captures the best of both worlds, yielding a much richer, fuller sound. These three models are similarly priced: LR Baggs Dual Source ($209 street), L.R. Baggs iMix ($229 street), Fishman Rare Earth Blend ($310 street).

Preamps and DI Boxes

If your guitar came from the factory with a pickup and onboard preamp, then you can ignore this section because you already have a preamp. But if you're having a pickup installed in your guitar, then you may need to consider whether to purchase a preamp to add into your signal chain. Another scenario that may prompt you to purchase a preamp is if your guitar has a passive pickup (one that doesn't require battery power). A preamp gives you the ability to add extra volume and shape the tones before they hit an amp or PA speakers. This is particularly useful if you frequently find yourself drowned out when you play with other musicians (or if you get a lot of feedback when you turn up to compete), or if you dislike the overall frequency response (bass, midrange, and treble) you get when you plug in. However, even active pickup systems can benefit from an external preamp.

Preamps come in different configurations, but the most common is the "little box on the floor" variety, such as the Fishman Aura Spectrum DI ($329 street), the L.R. Baggs Venue DI ($299 street), Ruppert Musical Instruments Acouswitch IQ ($TBD, rmi.lu), and the D-TAR Mama Bear ($349 street, d-tar.com). There are also rackmountable preamps that offer studio-quality sound and greater control over more parameters, and there are some guitarists who swear by them. But for most situations, those are overkill. "Small" and "easy" are two of the working acoustic guitarist's favorite words.

"DI" means "direct insert," and that means it provides enough tone-shaping capabilities to let you safely and satisfactorily insert your guitar's signal directly into a soundboard (or recording console or interface) that's feeding PA-system speakers. For a lot of gigging acoustic players, their DI is one of the handiest pieces of gear they will ever own. They range from super-simple conversion boxes (devices that transfer your guitar's 1/4"-cable signal to an XLR output you can plug into the PA system's mixing board) to elaborate and comprehensive sound-enhancement preamps like those mentioned previously.

The L.R. Baggs Para Acoustic DI ($169 street)—with it's easy-to-use 5-band EQ, phase-invert switch, and super-clean signal quality—is an industry standard. The L.R. Baggs Venue DI also enables you to add up to 6 dB of clean volume boost in a footswitch, which is incredibly handy for lead acoustic guitarists in any kind of ensemble, or for switching from strumming to fingerpicking. Here are two thrifty alternatives: Whirlwind IMP 2 DI (passive $50 street, whirlwindusa.com), Radial ProDI (passive $100 street, radialeng.com).

Amps

If you plan to play in situations where you'll need your own amplifier— either with a group of jamming buddies in your basement or in a smaller venue (see the Location, Location, Location sidebar, below)—there are many options. Besides varying in power output, speaker configuration, sound quality, and processing features (e.g., effects), they can also have varying numbers of channels (inputs for multiple sound sources). If you're just playing guitar, there are 1-channel amps, or you can get multi-channel amps that enable you to plug in your guitar and a friend's, and/or a microphone's XLR cable for singing along. (Remember, if your amp has a single channel with both an XLR and a 1/4" input, you'll only be able to use one at a time—because there will only be one set of volume and EQ controls.)

If you're looking for a small, affordable, great-sounding amp, we recommend you check out the ZT Lunchbox Acoustic ($399 street, ztamplifiers.com). For great sound and excellent versatility at a very attractive price point, be sure to look at the Fishman SA220 Solo Performance System ($999 street). If professional-quality sound is your priority, check out the AER AcoustiCube ($2,999 street, aer-amps.com), the Schertler Unico ($1,308 street, schertler.com), and the L.R. Baggs Core 1 ($1,199 street). And if you're going to need a lot of sound but don't want to carry around an entire PA system, check out the Bose L1 Model 1 Single System/Single Bass Package ($1,999 street, bose.com)—and be sure to get the bass module, because it is necessary to accurately represent your acoustic guitar's sound. Here's a couple more options: Behringer Ultracoustic ACX450 ($218 street, behringer.com), Ultrasound Pro250 ($980 street, ultrasoundamps.com), Genz-Benz Shenandoah Shen ProLT ($1240 street, genzbenz.com).

Acoustic vs. Electric Amps

Acoustic amps and electric amps are at least as far apart on the evolutionary tree as acoustic guitars and electric guitars. Yes, you can plug your acoustic into an electric-guitar amp and get sound out of it. But because electric-guitar amps are tuned to emphasize midrange and treble frequencies— and because they are usually designed to provide rock-approved distortion—they're not going to accurately represent your acoustic guitar's unplugged sound. That said, just as with effects, if you're not a purist and you don't mind risking a little feedback in order to give your acoustic a little attitude, give it a try. You wouldn't be the first to get a sound you like out of a nice vacuum-tube-driven guitar amp— famous players such as Ben Harper and Monte Montgomery have been known to do so.

Effects

Many acoustic guitar amps now come with built-in effects processing that enables you to augment your guitar's sound with reverb, echo (aka delay), and/or modulation effects that can run the gamut from thickening up your sound to lending it an almost psychedelic feel. The Trace Acoustic TA-100 ($999 street, traceelliot.com), for example, features modulation (chorus, flanger, phaser), tremolo (a hypnotic oscillation in volume), and a few different delays, while the more affordable Fishman Loudbox Mini ($329) has chorus and reverb. If your amp does not have effects and it's something you want to explore, there are staggering numbers of effects pedals available. However, the lion's share of them is made for use with electric guitars—though that doesn't necessarily preclude them from being used with an acoustic. In fact, if you're adventurous and not a purist, we encourage you to check out as many as you can. If you are more traditional acoustic fan, remember that a lot of effect boxes (aka stompboxes or pedals) can color the wound in a way that you'll probably find too radical. However, some effects types–particularly chorus and delay–shouldn't adversely affect your guitar's essential tone. In addition, some companies make effect pedals specifically geared for acoustic guitar, including these: Zoom A2 ($100 street, zoom.co.jp), Boss AD-3 ($169 street, bossus.com), Aphex Xciter ($200 street, aphex.com), Fishman AFX Reverb ($279 street), D-TAR Solstice ($329 street).

Go Forth and Plug In

The array of amplification options for acoustic guitarists may never be quite the smorgasbord it is for our electrified brethren, but there's never been a better time to decide to plug in your flattop. From pickups to DIs/preamps, effects, and amplifiers, the buffet of smart, practical, great-sounding products is extraordinary— and ever growing. With this guide in hand, a healthy dose of test-driving and research, and the advice of an experienced player with good ears, you're bound to find gear that's perfect for your jams and gigs. Sounds like a lot of fun, huh?

Location, Location, Location!

Where you play has a lot to do with both what gear you need and how you approach your gig. Here are some tips for venues of all sizes.

Church Gigs

Many people start their gigging careers with Sunday church gigs, and this can be great if not simply because the supportive and appreciative audience can really build confidence. Small, older, intimate, or low-tech churches don't always have sound systems that will handle live music, so they often use sound systems that only allow one signal to pass through at a time. In this case, a personal amplification system is absolutely necessary for the congregation to be able to hear every detail of your joyful noise. There won't be a lot of distracting noise, so you won't need anything massive. Usually, a 50- to 60-watt, 2-channel amp will do the trick unless it's a very large room— in which case you'll want something more powerful.

Big, modern churches frequently have theater-style sound systems with jacks built into the stage and speakers distributed throughout the house. For these venues, you'll need your axe, a guitar cable, and whatever EQ, effects, or preamp rig you prefer. Gotta love that simplicity!

Coffee House

Eating/drinking-establishment gigs can be some of the most frustrating performances ever. But because listening-room and concert-hall dates are few and far between for most of us, we're forced to make the best of playing at venues where we're simply part of the atmosphere.

An acoustic amp (with vocal channel, if that's part of your thing) will probably suffice in most places. However, if there's a lot of ambient noise from the kitchen and clientele, you may want to consider a PA system. A versatile, affordable system can be assembled with a small mixer such as a Yamaha MG102c ($99 street, yamaha.com), two powered speakers, and possibly a floor monitor. This is a time-tested way of making a lot of noise while sounding as much like yourself as possible—and it's a preferred option if you're working with an ensemble bigger than two. Entire publications have been devoted to PA systems, so we won't dwell on that beyond presenting it as an option.

If you don't need that much power but do need monitors, check out the Fishman SA220 or the Bose L1, both of which can be placed behind you to provide monitoring and the main signal at the same time. Either system can be used as a standalone unit—i.e., you can plug your vocal mic and instrument directly into them—or with a small mixing board to increase the number of channels.

Concert-hall and Festival Gigs

It goes without saying that hall and festival dates—the gigs where people actually show up specifically to hear you do what you do—are dream gigs for most acoustic aficionados. You almost always get to sound fabulous with a minimum of effort at these gigs.

Most of the time, the venue or event will supply the PA system, so all you have to do is show up with your rig early enough to get in a really good soundcheck. Many acoustic amps have a direct-out (DI) output on the rear panel. This is handy because it allows you to send your signal to the PA and retain control of your EQ and effects settings, while letting the sound tech simply handle levels. If you don't know the sound tech (or perhaps if you do), this can be a great way to ensure you sound like you, rather than a craptastic version of you. (If you haven't already discovered this, you will eventually: There are some wonderful sound techs in the world … but there are also guys who end up running the board because the regular guy has the flu.) Even better, if you use your amp's DI function, it also enables you to use the amp itself as a monitor. Another option is to mic the cabinet, but this can be tricky with acoustic guitar amps, and should only be done by a really good, experienced sound tech.

Concert halls are usually optimized for acoustic music— usually classical or jazz—and therefore minimal sound reinforcement is needed to present the full harmonic and dynamic range of the music. In these scenarios, a less-is-more approach is often the way to go. If ever you are going to simply mic your guitar, this is the place—that is, if you or the venue has a high-quality stage condenser that can capture all the detail that wooden baby has to offer.

Conversely, at an outdoor festival, the sound seems to leave your instrument and disappear. Depending on the configuration of the stage, it can be hard to get enough of a monitor mix without getting feedback, which makes it hard to know how you actually sound to the audience. As you can imagine, this can be very frustrating. Not being able to hear yourself causes a multitude of problems, not the least of which is wearing yourself out by overplaying and oversinging. Be patient, be willing to compromise, and have respect for the sound tech—that's the best way to handle these situations in a way that doesn't look unprofessional to the crowd and make enemies with the sound crew. The last thing you want to do is alienate the guy who controls how you sound out front.

The other festival frustration for acoustic artists is that the acoustic stage is frequently stuck with leftover gear so that the bigger- drawing electric bands can have the good stuff. I once played a festival where my awesome hi-tech active pickup was overdriving the antiquated and poorly maintained board so badly that you could hear nothing but distortion. I now have a guitar with a passive K&K Pure Mini pickup for these kinds of situations, and I never leave home without an L.R. Baggs Para Acoustic DI. Lesson learned.

[Updated 10/13/21]