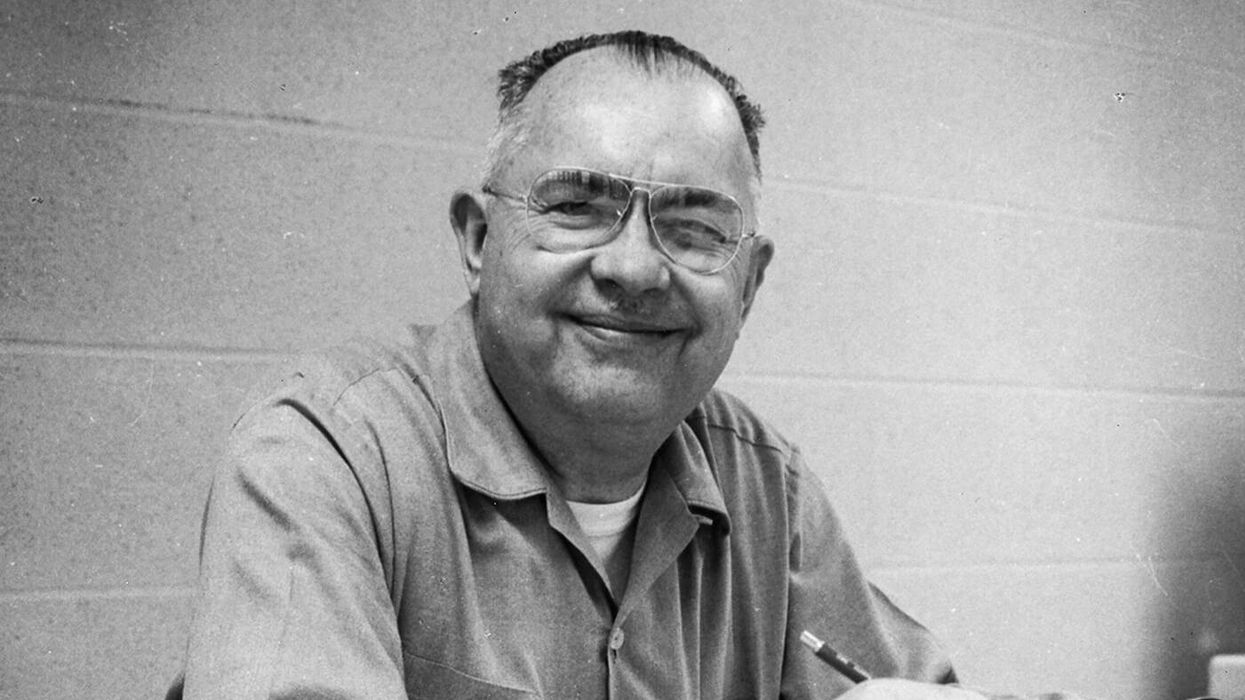

Hello and welcome back to Mod Garage. This year, Fender is celebrating its 75th anniversary. In honor of that, let's take a deeper look at some Fender history—exploring some myths and urban legends, all while celebrating the man behind the company that started it all: Mr. Clarence Leonidas Fender (or, as the world called him in short, "Leo").

Leo Fender, the father of the modern electric guitar, was born on August 10, 1909, and died on March 21, 1991, at age 81. Much has been written and published about this man, but still today there are some myths related to him that often cause misunderstandings.

Don't get me wrong: It's absolutely not my goal to downplay the reputation, the importance, or the work of Leo Fender. If I had a time capsule (or a Mr. Fusion that outputs 1.21 gigawatts for my DeLorean) and the chance to meet three people in history, Leo Fender would be one of them. I have a picture of him in my workshop with the imprint, "What would Leo do?" It often really helps me to try to think like Leo Fender to solve a guitar or amp problem.

Let's examine some common statements you might read in a lot of guitar books, mags, and, of course, on the internet. Below each statement is some historical context and my thoughts on the big-picture reality.

1. Leo Fender invented the electric guitar.

This is a common statement that's in wide circulation, but from today's knowledge we know it's not true or at least not the entire story. The attempts of putting homemade pickups and microphones on guitars (mostly acoustic guitars) dates back as far as the 1920s. Leo Fender started putting pickups on solidbody guitars in the mid 1940s, but it's very likely the initial idea for doing so came from Paul Bigsby, who built solidbody guitars only a few miles away from Leo Fender. It's known that Paul and Leo were friends and it's also documented that Leo Fender borrowed such a guitar from Bigsby over the weekend to examine it. But neither Leo Fender nor Paul Bigsby invented the electric guitar. This credit goes to Paul H. Tutmarc, who did so in the 1930s. For sure Leo Fender could be called the father of the modern electric guitar because he made it popular and set up a system for mass production to build great instruments in large numbers.

2. Leo Fender invented the electric bass.

Another statement that can be found on countless pages, but again, it was Paul H. Tutmarc with his "bass fiddle" in the mid 1930s, long before the Fender Precision bass appeared on the scene. Tutmarc's 42" Model 736 Bass Fiddle looked like modern electric basses still look today, and he also sold amplifiers for his instruments. But Leo Fender came up with a real bass lineup, including several bass amps that were specifically designed to not only amplify everything, but focused on electric basses.

3. Leo Fender put out-of-phase sounds into the Stratocaster.

This is a common misunderstanding and perhaps a product of the creative use of technical terms that Leo Fender had. Leo called the Stratocaster's vibrato effect "tremolo," and his amp's tremolo effect "vibrato." So maybe he called the "in-between" pickup positions (bridge + middle and middle + neck in parallel) "out of phase." Naturally, they were still in phase and not out of phase. Leo Fender didn't like these sounds, so the 3-way switch stayed standard on all Stratocasters until the early 1980s when 5-way switches became the standard. It wasn't that they didn't exist earlier, it was because Leo Fender didn't like the "in-between" sounds. But those sounds, with their decent phase cancellation and slightly reduced output, are so popular today that even a new word was created to describe them: "quack."

4. Leo Fender invented the six-in-line arrangement of the tuners on the headstock.

This is simply wrong. It's likely this is another idea he borrowed from the electric guitars Paul Bigsby was building and that Leo closely examined while having access to such an instrument over the weekend. Paul Bigsby used the six-in-line arrangement of the tuners on his guitars exclusively, but he wasn't the inventor of it. This dates back to Vienna in the early 1800s and one of the finest names in international lutherie: Johann Georg Stauffer, who lived from 1778 until 1853. This was the man a certain Christian Frederick Martin (or C.F. Martin, for short), who lived from 1796 until 1873, learned his art from ... maybe you've heard of him.

If I had a time capsule (or a Mr. Fusion that outputs 1.21 gigawatts for my DeLorean) and the chance to meet three people in history, Leo Fender would be one of them.

C.F. Martin worked with Stauffer from 1811 to 1825 and became the foreman at Stauffer's workshop. In the same year Martin left Stauffer, his former boss came up with the invention that went down in history as the "Stauffer headstock," or, as it's originally called in German, "Stauffer Schnecke." Specifically, that is: a metal plate with an asymmetrical "scroll" headstock, machine heads with worm gears mounted on the plate, arranged in a single line on the upper side of the headstock (six-in-line). It's likely that Stauffer worked on this design for a longer time and that C.F. Martin was involved in this process. The rest is history, as they say. Martin emigrated to the United States in 1833, where he introduced the mechanism developed by Stauffer and founded Martin Guitars.

5. Fender used magnets with beveled edges for the Stratocaster pickups for some time, like those found on Rory Gallagher’s famous Strat. These pickups sound much better than the modern flat pickup magnets and Leo Fender did this because of the better tone they provide.

This is my favorite rant 'n' rave topic when it comes to Fender. Yes, these pickups sound different because the beveled edges influence the magnetic field a lot. The physics behind it are very complex, but in layman's terms, these pickups sound fatter with more overtones and a not-so-shrill high end. This had to do with the different "magnetic window" the pickup has (the so-called "aperture"). The early magnets had hand-beveled edges and it was generally assumed this was done to disguise the rough and uneven surface left by the sand casting. However, this can't be the reason, because doing such handwork takes a lot of time and care to do it right and Leo Fender wouldn't spend any time for such unnecessary things in his building process.

Later Fender stopped beveling and the sound of the pickups changed because of this. Seymour Duncan once wrote a very good explanation about this: "The bevel causes the magnetic field to shoot out a little around the bevel area, but it results in a tapering of the field above that point. So, if you could, imagine the magnetic field shaped like the flame of a candle or a teardrop." An excellent metaphor that hits the nail. But why did Fender start with hand beveling and why did they cease with this process later? Was it because of the better tone of the pickups? I don't think so. Leo Fender was driven to make his guitars sound outstanding and he would never stop such a process if it would influence the good tone of his instruments.

I think the answer must be seen in the historical context of the time. Fender started hand beveling the magnets and, sound-wise, this was a stroke of genius by accident. The alnico 5 material used for the magnets was brand new and very expensive at that time ... and it was very porous as well! A lot of the magnets crumbled while using a hammer to drive them into the pickup, which was the usual procedure in the Fender factory. This can be seen on several pics and videos from that time. So, they simply beveled the magnets on one side to minimize the risk of destroying the magnet during the hammering process. Depending on the employee standing on the sanding machine, the edges are more or less beveled from pickup to pickup, which is one of the reasons why the old vintage Strats sound so different from guitar to guitar. Rant over ... for now.

6. Leo Fender carefully calculated the values for the treble-bleed networks that Fender started using in the late 1960s.

We've discussed the treble-bleed subject several times in the past and the physics behind this little detail are very complex in a passive system. It's possible to calculate a good working treble-bleed network, but you need a lot of parameters for this (length and capacitance of the guitar cable, input impedance of the amp, resistance of the volume pot, etc.) and some complicated mathematic formulas like the Fletcher Munson Curve theory. Fender used a single 0.001 uF cap (1000 pF) together with 1 Meg audio pots in their Telecasters. Calculating this with the parameters mentioned above will result in a very different value and, of course, the presence of a resistor in parallel to the cap. So, we can deduce that it wasn't calculated but narrowed down in a trial-and-error process by ear. If you've played such a Telecaster, you know the sound when rolling back the volume is very shrill and even a reggae or surf player will say, "Wow, this is a lot of treble!"

So why would Fender use such strange values for such a brutal portion of high end? I think the answer is that Leo Fender did this by ear in a trial-and-error process and that it sounded good for him. Taking into consideration that Leo Fender sadly lost most of his hearing because of an accident in the factory, wearing hearing aids for the rest of his life, it makes sense. The first frequency you lose is the high end and 1960s hearing-aid technology was far away from what it is today. It seems Leo Fender did his best under the given circumstances and I'm pretty sure it sounded good with the correct portion of high end for him. And Leo was the boss whose word was law.

7. Leo Fender chose nitro lacquer for his instruments because of tonal reasons.

Definitely not. Fender used nitro lacquer right from the start because in the mid 1940s, inexpensive industrial-made acrylic lacquer simply didn't exist. Nitro lacquer was used since the 1920s throughout the automotive industry and, therefore, was readily available everywhere, inexpensive, well proven, and relatively easy to work with. Fender's main goal was inexpensive mass production, so Leo simply used what was locally available for a decent price. It's well known and documented that Fender bought nitro lacquer from a local automotive supplier. Over the years, acrylic lacquer became the standard in the automotive industry, superseding nitro lacquer completely, so Fender switched to acrylic lacquer in the late '50s as well. If Fender had chosen nitro lacquer because of tonal reasons, they wouldn't have switched over to acrylic lacquer for sure. A funny sidenote: Some of the most-famous '50s Fender custom colors like "Olympic White" or "Lake Placid Blue" never existed in a pure nitro finish. They were painted with acrylic lacquer and only sealed with a thin layer of clear nitro lacquer topcoat.

That's it for this round of myths and urban legends. Happy Birthday Fender and all the best for another 75 years. Next month, we'll take a closer look into splitting and tapping pickups and what the difference really is, so stay tuned.

Until then ... keep on modding!