Some time ago, home recording was a field largely occupied by ambitious amateurs who weren't quite ready for a pro studio and wild eccentrics whose limitless creativity knew no bounds. This made the rare home-recorded release a special treat, and albums by artists such as Brian Wilson, Daniel Johnston, and Guided By Voices gave us a glimpse into their raw creative processes. But as the ubiquity of laptop DAWs replaced 4-track machines and portable digital recording consoles as the de facto home setup, the field became democratized.

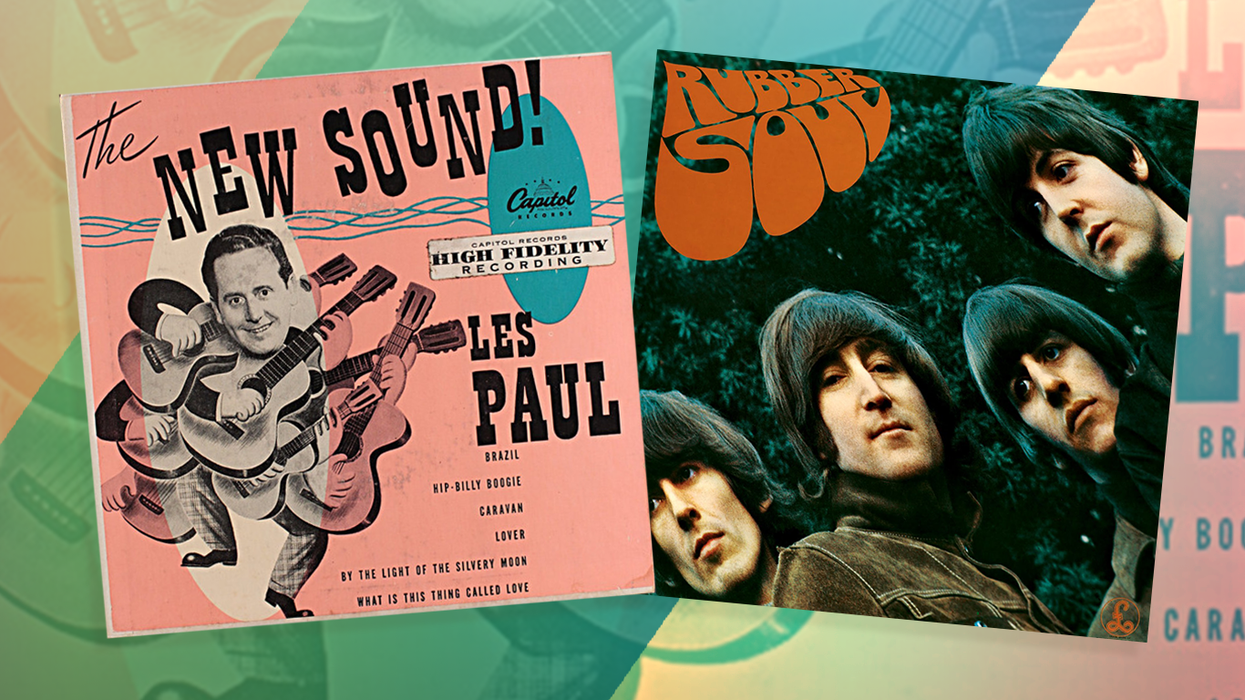

It's not news that recording gear has gotten cheaper in recent years. Nowadays, for the price you would have paid for a low-end 4-track back in the '90s, you can buy a mid-level interface, monitors, and a decent enough microphone to make studio-quality recordings. "If you've got a [Focusrite] Scarlett, an SM57, and Ableton Live, you have so much more in front of you than the Beatles ever dreamed of having," says Dave Fridmann, producer/engineer and owner of Cassadaga, New York's Tarbox Road Studios, who has famously mixed home-recorded albums by Tame Impala and his longtime collaborators the Flaming Lips. "There's no reason why you can't do anything you can think of with that gear. Anything." If that's not encouraging enough, consider that even major-label artists such as Fiona Apple and guitarist-producer Steve Lacy have, at times, avoided high-budget studio sessions, opting to record at home and use the same inexpensive tools that are accessible to the rest of us.

While those of us who want to can—and, during the pandemic, most likely did—get to work on our next masterpiece in the comfort of our homes, some limits remain. And for many of us who have been recording on our own, the biggest limitation may be our own ability to mix. What do we do when it's time to make the final decisions on how our tracks should sound? It might seem intuitive, but anyone who has ever tried to mix his or her own recordings knows that the right sound can be hard to nail down and the limitless list of plug-ins can be overwhelming. Lucky for us, there are plenty of professional engineers who are ready to mix our home recordings and elevate them to the level of sonic majesty. With that in mind, we tracked down four of our favorite engineers and discussed the process of having an engineer mix our home-studio tracks.

When Two Brains Think as One

Artists should feel free to reach out to their mixing engineers as early in their recording process as possible, says Jarvis Taveniere, who is happy to share helpful tips with his clients, from brainstorming mic placement to setting up a room.

The very first step is to find the right person for the job. You'll probably want to pick someone who has worked with bands you know, bands you like, or bands you think sound like what you're working on. You should feel comfortable reaching out to engineers and asking questions. Good engineers are only going to want to mix your record if they feel like they can add something to it, and you should feel the same way about them.

Jarvis Taveniere, who plays in the band Woods and has engineered albums by bands such as Fleet Foxes, King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard, and Real Estate, tells us that it's of utmost importance that an artist and engineer really click. "I don't want to have to convince people that their vision of their song is wrong," he says. "If I don't like their vision of it, then we shouldn't be working together, and I say that with love."

"It's cool to listen to yourself through one mic and be like, 'What does it sound like? Does this sound good? Does it sound harsh?'" —Jarvis Taveniere

You'll also want to consider how you'd like to work together. It's always fun and can be instructive to attend a mixing session, but if you don't have a good fit locally, remote mixing opens up your options to just about anyone you can think of—who fits your budget, of course. Technical details may narrow down your search, too. But don't be dissuaded if it doesn't make sense to work with the engineer of your dreams right now. Every engineer has his or her own way of mixing, and that means different requirements for the files you actually send them—more on that later. And if you've already recorded your album without your engineer's parameters in mind, you may have more limitations than if you haven't gotten started.

Before You Hit “Record”

The engineers we spoke with agreed that, most of the time, clients don't reach out about mixing until their recording is mostly finished. But if you're considering tracking at home and can figure out who you'd like to work with before you begin, that mixing engineer can offer some insight about recording and collaborating.

Taveniere says contact before recording is his "perfect scenario," and believes it can be helpful to discuss things such as mic selection, mic placement, and even simple room treatment options to avoid potential mixing headaches. For example, he explains, "The room is important. If you're recording something at home, close-miking guitar amps is easy and you can do bass and keys direct, so the few things that can have ambience can open up the record. If you're in a room that's rectangular or square, with parallel walls, and you have a condenser on an acoustic, you're probably gonna hear some of the room, you're gonna hear some of those reflections." With the help of a sample recording and a photo, he's happy to help clients get a warm and focused room sound. "Throwing down some rugs, building or buying some 2'x4' absorption panels … it's fun to set up your space so you can have a good sounding room." Addressing such issues in advance will not only make mixing easier, it may give mixers like Taveniere more flexibility to make their mark on your recordings.

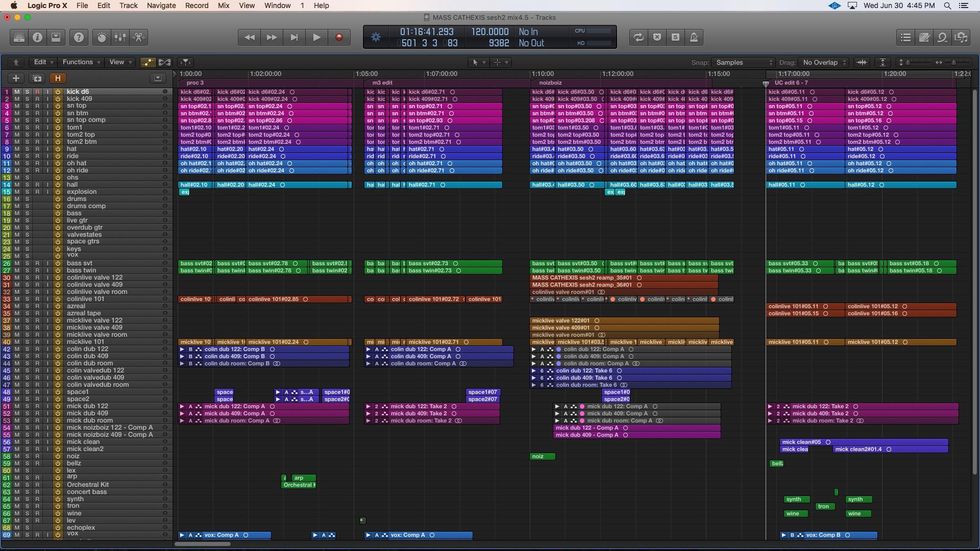

Colin Marston, seen here hard at work at his Menegroth: The Thousand Caves studio, advises you to keep your tracking levels low.

If you're not ready to commit to a mixing engineer before you start tracking, there are some simple tips you can follow that will make things easier later. "Use minimal mic setups, one or two mics at the most, especially when you're in a practice space," recommends Eric Bauer, who runs Bauer Mansion studio in San Francisco, where he's worked with Thee Oh Sees, Ty Segall, and many more. Taveniere agrees, adding, "It's cool to listen to yourself through one mic and be like, 'What does it sound like? Does this sound good? Does it sound harsh?' You can make adjustments if you go slow and think about it, and make decisions."

This is very easy to apply to electric guitar tracking. "If you put a mic in front of it and get a level that isn't clipping, that's good enough for me," says Colin Marston, who runs Menegroth, The Thousand Caves studio in Queens, New York, and plays in Gorguts, Krallice, and Dysrhythmia. This is also a reminder to be sure to record with enough headroom. Once a level clips, it can't be undone. As for common fears about recording too quietly? Marston assures us not to worry, saying, "With 24-bit audio, we have more headroom than you could ever hope to hear, so it's better to shoot a little bit conservatively when it comes to that."

Know Your Tones

Straight from Colin Marston's desktop: an organized session with easy-to-understand labelling.

Some guitarists who record at home are unable to capture the sounds they want. Others are capable of getting their desired tones, but need help taking their project across the finish line. For players in the former camp, Marston recommends reamping. This means the sky's the limit when it comes to guitar tones. And it's a godsend for guitarists seeking the sound of a big, cranked amp, but who can't get that at home.

"The definition of reamping is running anything through another amp," explains Marston. "If I take a signal that's already been miked and run that through an amp again [and record it with a mic, again], it's like a game of telephone: You're gonna get a really blurry, weird signal that no one is used to hearing, because it's being filtered twice through this process that we're only ever used to hearing it filtered through once." Because of this, it may be ideal to plan to reamp your signal from the start, and to perhaps record your original guitar part via DI. "For reamping to sound undetectable, it's gotta be via a DI signal of some variety," Marston adds. "That can be a straight DI or a signal that has been run through a simulator, pedals, or the preamp stage of an amp. Different engineers may have different opinions about which signal they receive."

"With 24-bit audio, we have more headroom than you could ever hope to hear, so it's better to shoot a little bit conservatively." —Colin Marston

Reamping can be a time-consuming process, since the engineer is effectively re-recording your takes, but it all depends on what you are trying to achieve. "That's one of those things you have to estimate at the beginning," Marson says. "Is this time and investment to shorten the overall session or is this going to unnecessarily add time where the tone they've got already is pretty good?"

But it's ideal to just find a sound you love and get it printed. "What's happening now is that people are recording flat: They stick a mic in front of something and they record it and then they shape the sound," says Fridmann. "I don't encourage people to do this. I think it's a much better idea to get a great sound, something with character that fits the tone of the song you're working on, and print it and be done with it and don't go back. I don't want to—and you don't need to—fiddle with plug-ins for six weeks. If you've got a sound you think is cool, print it and move on.

Delivering Your Tracks

Here's a quick check-list to help make your tracks mix-ready:

- Make sure there's no clipping on your track levels

- Label your tracks, clearly and cleanly

- Turn off master channel processing before bouncing tracks to a sharable format

- Send WAV files to avoid audio quality loss

- Use a sample rate and bit depth of at least 44.1kHz/24-bit

- Provide rough mixes with your tracks

- Use zip files or another means to compress files before emailing

"You can leave it up to the mix engineer, but I don't see why you would. From my standpoint, that's a production decision. If you send me a clean guitar that has no processing on it, but you're expecting it to be distorted, we've got way too much to talk about, and I'm trying to mix this song today."

Audio File Hygiene

At the start of every mixing session, Eric Bauer will run a client's rough mixes through his board to help them hear what they can expect from his signal chain.

Most of the engineers we spoke to ask their clients to send them separate synced audio files accompanied by a rough mix. This provides the most flexibility while letting them hear how you're imagining the final recording. Some engineers prefer to have a DAW session as well, so this should be part of any conversation before you get started working together.

If you're bouncing down individual tracks, it's important that you understand exactly what you need to do to make the compiled tracks work. And if you don't, talk to your engineer. Most DAWs make it quite easy to export synced tracks, while others, particularly GarageBand, do not.

"Use minimal mic setups, one or two mics at the most, especially when you're in a practice space." —Eric Bauer

Bauer explains the dangers of bad exporting: "People bring over files and they'll be not synced, not to the same length, so we'll have to sync them up in Pro Tools, which is never completely accurate. I'll have random guitar solos, an overdub of a guitar solo, and I'll have to move it. That's one of the big problems I get."

Whether you're sending separate WAV files or DAW sessions, every track needs to be effectively labeled in a universal way that will help your engineer quickly understand what they're looking at. In an ideal situation, your engineer will spend time mixing and not navigating extensive file names, trying to figure out what's going on with your tracks. That means keep your labels short and clear—Marston offers "GTR U87" as a short label anyone mixing a record would understand—and keep your folders organized.

Second That Emotion

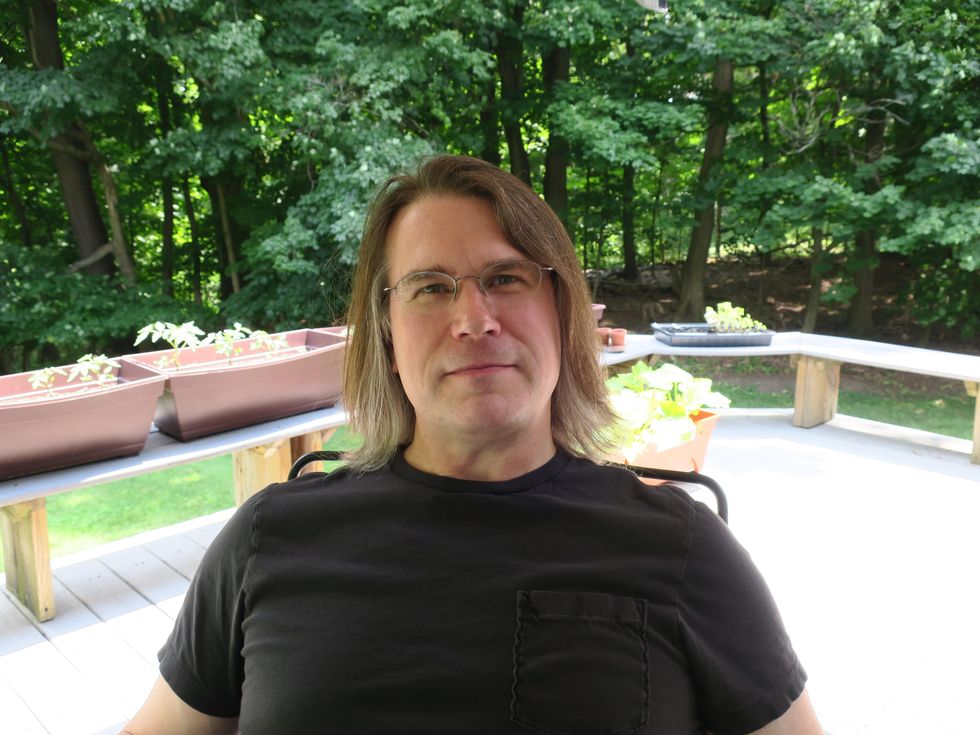

Dave Fridmann encourages home recordists to focus on songwriting and getting cool sounds, and to let mixing engineers worry about the technical details.

When Fridmann mixed Kevin Parker's self-recorded Tame Impala debut, Innerspeaker, Parker flew from Australia to Tarbox Road to mix the album. When they completed the mix, both felt satisfied with the result. But Parker changed his mind upon returning home and flew all the way back to work with Fridmann on a remix. Sure, it was a lot of extra work, and Fridmann says both mixes sounded good, but he agrees that the final version was the better of the two. That just goes to show that there is more than one way to mix a recording. Everyone hears music their own way and the best finished product is what sounds best to the artist … and even that can change. What mixing engineers do is help us hear what is possible and bring that to life.

"If you've got a [Focusrite] Scarlett, an SM57, and Ableton Live, you have so much more in front of you than the Beatles ever dreamed of having." —Dave Fridmann

As artists, we can spend months or years listening to our recordings at home, and anything outside of that can sound surprising. We just need to keep an open mind. While Bauer says that artists often "have it in their mind that those roughs are the one," he has his own strategy to help them hear new possibilities. "At the start of every session, I'll put [the rough mix] up on my board just as they have it, and I'll do a rough mix of their mix running through my two-bus mixing chain. I'll have a bus compressor and a bus EQ, and I'll run their whole mix through that before I start doing anything. Then, we'll start mixing and I'll do it the way I think it should be done. When they leave here, they have three mixes to choose from: their original mix, their mix through my board, and my mix."

Eric Bauer cautions clients to make sure their files are synced correctly.

Fridmann cautions against getting bogged down in the details, because ultimately there's no replacement for good writing and solid playing. "You've gotta have faith in yourself," he says. "No mix engineer is gonna make you say, 'Oh wow, this was mediocre and terrible, but now it's great.' If there's some spark there, if there's something that's musically engaging to you already, then mixing will exemplify that.

"It's not about the technical issues," he continues. "Yes, we have to solve all of these things and maybe somebody hears something weird in some frequency range. Fine—we'll address all that stuff, but that doesn't matter. It doesn't matter when you hear 'Baby Love' and it doesn't matter when you hear 'Back in Black.' Those aren't technical issues that we're listening to—we're listening to emotions and that's what mixing is about to me."