As a lover of sound, I'm guilty of tunnel vision when it comes to guitar and bass amplifiers, often emitting a low groan when I arrive at a stage with backline gear not to my liking. It's discriminatory and, in fact, my judgmental eyeballs do this with almost every object on the planet.

So, I decided it's time to make an attempt to break out of my comfort zone and preconceptions, and let my ears decide what's best for a given stage or studio situation—while giving my biased peepers a rest. To help me get a fresh perspective and possibly reinvent my concept of what sounds good, I enlisted two colleagues, Jamie Stillman and Ben Vehorn of EarthQuaker Devices, to shed a little light on my otherwise dark and singular path. I also work at EarthQuaker, and I'm a pedal and amp builder. Jamie is the genius behind some of the coolest effect pedals out there, while Ben has worked in studios for years, earning a unique perspective on the audio-capture end. I also enlisted a half-dozen intriguing examples of vintage transistor titans and tiny terrors. Our goal: to open my heart and mind—and maybe yours, too—to some great sounding solid-state amps.

Enter the Wayback Machine

Before we get cracking, let's take a trip back through time to get some footing in amplifier topologies. In 1906, Lee de Forest—the self-described “Father of Radio"—improved the basic valve diode by including a separate, third electrode, thereby inventing the main building block of early tube amplification. Fifteen or so years later, this starts getting called the “triode," sensibly enough. Sounds science-y and cool, right? And as we approach the middle of the 20th century, the pentode (with five working elements) starts to show up and becomes a mainstay in the world of vacuum tubes. These new devices were perfect for the requirements of wartime, with lower manufacturing costs and greater versatility. They were also great for amps, because with each new element in the tube, bandwidth, tone, and feel characteristics improved.

Then along came transistors. The first patent for a transistor was issued in 1925, but things began to get serious in '47, when Bell Labs in New Jersey started experimenting with germanium crystals made in a lab, and discovered their ability to create output power greater than their input. That led to the first practical transistors for mass-production, based on those lab-cultivated crystals. (Yep, that's right. Fuzztone was born in a petri dish!)

Bell Labs was quick to slap a patent on this new wonder, and the first transistor radio appeared in 1954 with germanium diodes—the first solid-state semiconductors on the scene—inside. Later, as with tubes, a third electrode was added to the mix, and the germanium transistor you know from “Purple Haze" was born.

One commonly known limitation of germanium transistors is temperature instability. They get hot and start performing shoddily with regards to linearity and gain. To combat this phenomenon inherent to germanium, silicon was used for its abundance and better performance characteristics under metaphorical fire. Silicon is also the second-most-copious element on Earth, next to oxygen. And it conducts electricity excellently, and that only gets better with heat. Silicon transistors operate by passing electrons through a solid material—silicon crystals—which act as a semiconductor. Sometimes silicon transistors are referred to affectionately as “sand-state" because sand is composed of silicon. Tubes are sometimes referred to as “hollow-state" because they are either gas-filled or—like amp tubes—have a vacuum inside. This open space is where all the aforementioned elements of the tube do their magic.

Once silicon became the new champion of transistors, solid-state amplifiers were off and running. In fact, solid-state became the go-to status for all kinds of products. Another appealing advantage of solid-state technology is that it requires much lower operating voltages than high-voltage, high-impedance tubes. The low-impedance signals typically spit out by transistors are also great for driving low-impedance speakers, while tubes need an output transformer to take the tubes' high-impedance output and match the signal with speakers.

Since solid-state amps don't need an output transformer, they have a much lower weight than tube amps. That's a win for maker and end-user alike. The power transformer is also slimmed down. Since transistors operate at much lower voltages, they make it easy for lightweight power transformers to supply the DC voltage to fire up an amp.

Think of it this way: The wall at my house puts out 117 volts AC. To feed the tubes, I gotta step that voltage up inside the amp at least a couple of times to get what I need. That takes a big power transformer. Then there's the heater winding of the tube amp power transformer, adding yet more weight. But a solid-state amp is taking the 117V AC from my wall and stepping it down to around 50V DC after rectification. This less taxing exchange typically makes the power transformer smaller in solid-state amps. So, the less iron an amp has inside, the easier it can be lifted.

This simpler construction also means less can go wrong. And solid-state amps also have less of a shock hazard. Tube amp operating voltages are significantly higher than what exits in the wall, and they have high levels of DC voltage, which can really zap you and keep zapping you, since there is no rise and fall through the zero crossing, which happens with the AC voltage that powers solid-state designs.

That Other Tube Bias

So cool—those are the basics. What about the differences in sound?

Tube amps are said to be “warmer" and solid-state (aka transistor) amps are typically called “flatter." When I ask most of my pals about the sonic differences between tube and solid-state amps, that's the consensus. But why have these generalizations become common?

I think it stems from each device's saturation characteristics. Tubes are slow and unpredictably predictable—the way a tube distorts and produces harmonic non-linearity, the way it interacts with other tubes later in the circuitry. Transistors, on the other hand, take what you give them and barely wince. They do a tip-top job of not imparting additional color to the sound going through them. They are also much faster devices than tubes, which translates to a more immediate sound and feel. This isn't to say that tubes and transistors can't sound just like one another, because they totally can and often do! If you give musicians a blind listening test of different tube and transistor audio circuits, there's gonna be some crossover in the answers. Well, at least in my own.

But generally speaking, I'm with the crowd on the difference-in-sound debate. If I want a pushed guitar sound that only gets more unhinged as I crank the amp up, it's tubes. If I want a balanced, even sound for my new guitar no matter what venue I'm in and where the volume knob is set, that's solid-state.

It's not really this cut and dry. When considering your own options, use your ears to find your sound—even if it's just for today. You can always change amps again tomorrow.

So, armed with all that, let's bring one of our experts, Jamie Stillman, into the conversation.

Jamie Stillman's first solid-state amp was a '70s Sunn Beta Lead, a 100-watt monster with high headroom and booming lows, capable of handling effects geared for low-end sounds and running clean at high volumes. These days, Sunn Beta Leads in good condition sell for about $500. The Melvins' Buzz Osborne is a die-hard Sunn Beta Lead user.

When did you begin to discern the difference between tube and solid-state amps?

When I was playing drums in [Kent, Ohio-based '90s band] Harriet the Spy, I think Joel [McAdams, a fellow band member] had a Sunn Beta Lead. I was looking for a new amp. You could find those solid-state Sunn amps any day of the week for, like, 40 bucks. It just sounded better than the JCM900 I was using at the time. Back then I didn't really know what solid-state meant, I just knew it didn't have tubes. The benefit of solid-state amps is higher headroom before distorting. The Sunn had that. It also just had more low end. That's what I liked at the time. Then I sold those and got a Bassman head. After that I got a Music Man HD 130, and that's when I started really paying attention to amps. [Editor: Early-'70s Music Man HD-130s have a solid-state preamp with a 12AX7 phase inverter tube.]

Take me through your hybrid Music Man-era rig.

I don't remember how I found out about the Music Man. I think I was looking for something that sounded like a Fender, but would never distort—that I could just keep making louder. That is what totally drew me to it. You could run lower octaves at it and it wouldn't blow out or distort. Then you could just keep adding more and more boost to it and it would just get louder. I never had an issue with it not being loud enough. And that's what I think I do a lot of the time—just keep adding more and more volume.

Then it makes sense that you'd be expanding into higher headroom amps.

I know it's not a popular opinion, but I really like solid-state amps, a lot. But now, I'm using a Marshall Super Lead and a Sunn Model T—both tube amps—which totally goes against that.

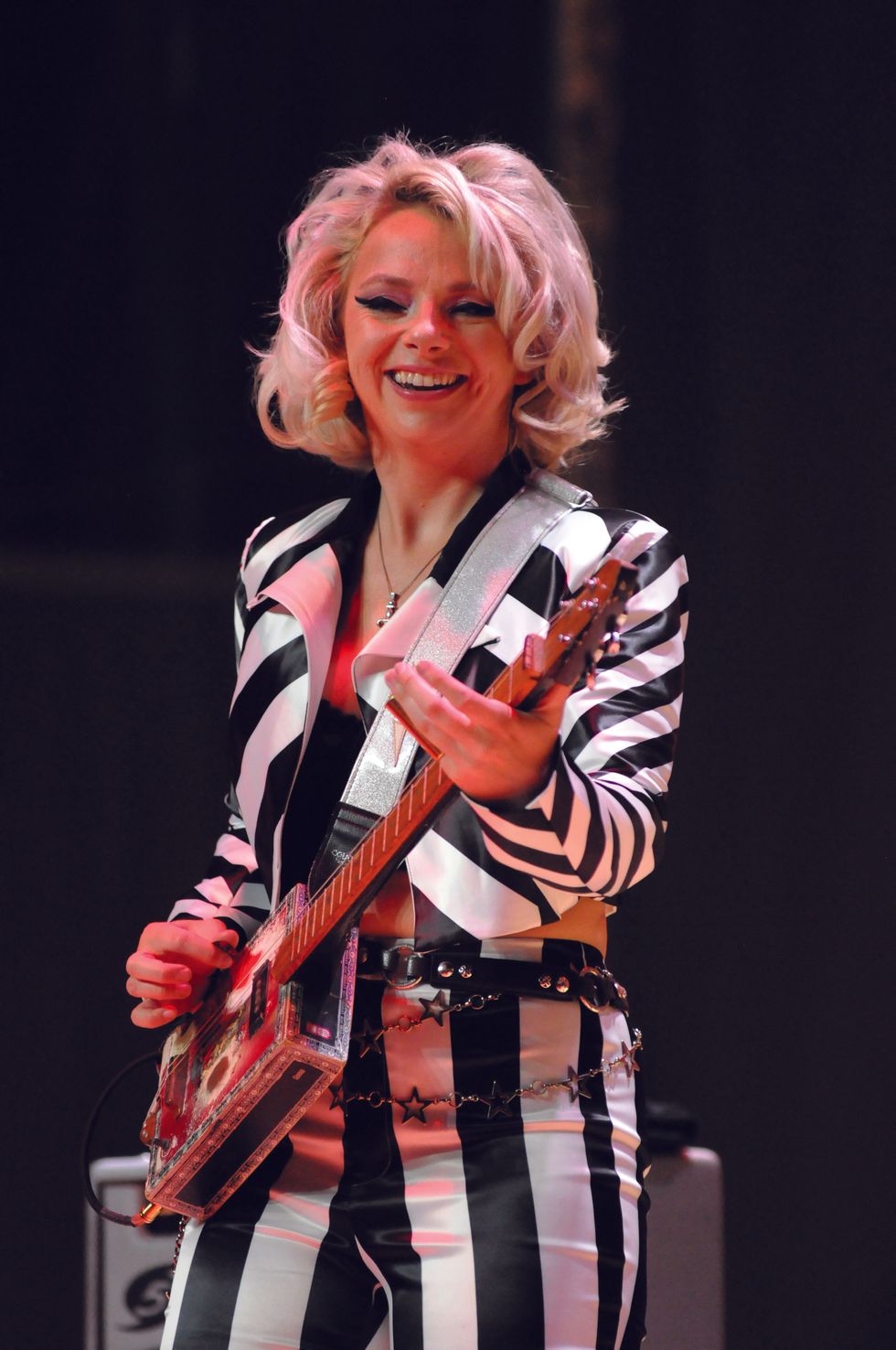

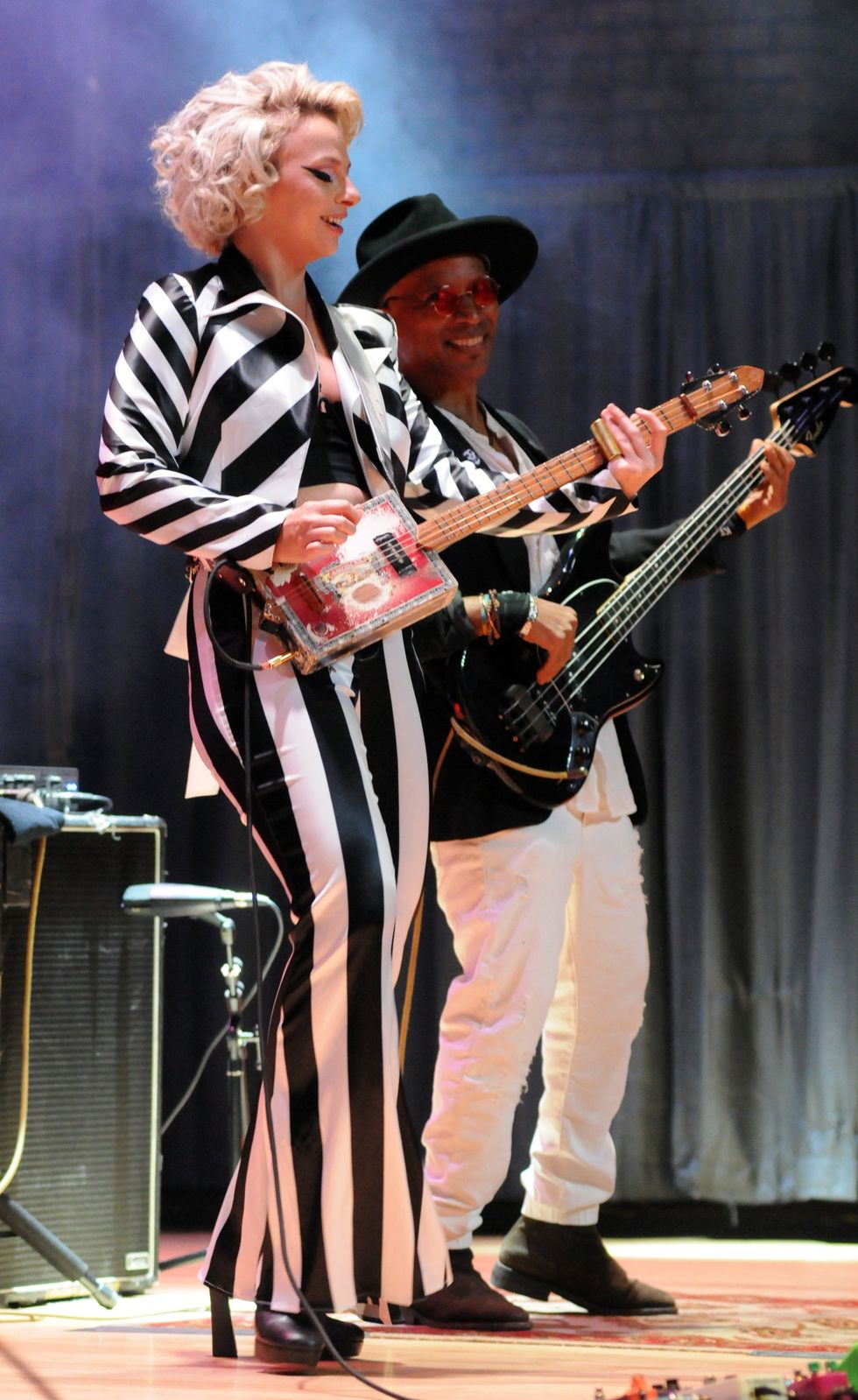

Designed to compete with Fender's Twin Reverb, the Music Man HD-130 boasted 130 watts and four 6CA7 output tubes—a version of the EL34. But this '70s creation had a solid-state preamp circuit. In later models, the 12AX7 phase inverter tube was also replaced with solid-state circuitry. The result was an amp with lots of headroom and clarity, and it found favor with a diverse range of players, from Aerosmith to Mark Knopfler. Today, they are available as reissues, and vintage models start at about $700—and can run hundreds more—for a combo in good condition. This road warrior is owned by Joan Jett.

So what is the discernable timbral difference between tubes and solid-state for you? You mentioned headroom and bass extension.

I'd say the headroom. The one negative thing I'd say about solid-state is that it's flat. No matter how you EQ it, it kinda sounds dead.

Which can become increasingly apparent when you crank it up.

Yeah, I'd say so. As you may know, I made the Speaker Cranker [overdrive pedal] for the Music Man, in an attempt to make it not so flat.

For bass, I use a solid-state Ampeg SVT-450, and I love the way that amp sounds. It does what I want it to do: It sounds like Jesus Lizard.

What's the coolest-looking solid-state amp?

I like the '70s stuff. Acoustics look really cool. Some of those late-'70s Peavey amps look really cool too. They look like a '70s version of the future.

With all the class D and hybrid designs tumbling out these days, do you think there will be a boutique solid-state renaissance that harks back to those classic-era designs and the '70s aesthetic?

I'm shocked that nobody has done it. I mean, it's not easy, but the availability of parts is higher and the cost is lower. I think that if anyone were to make a solid-state amp look cool, you'd probably sell a ton of them—even if it's light, if it just looked like a regular amp. In the end, if you do a thing where you like to stack multiple gain stages, or if you're trying to get louder without compressing or distorting, a solid-state amp is totally the way to go. If you're looking for more defined sub-octave effects from your pedals, or for the pedals to sound more like themselves, solid-state is the way. It just sounds more pure. But I guess it all just depends on how you play.

As our conversation wound down, Jamie mentioned a little solid-state head that he liked primarily for its tremolo. So let's take a look at the Teisco Checkmate CM-25.

Checkmate model line came in a variety of wattages and in both tube and solid-state editions. A rare version of the CM-25, in rolled and pleated vinyl covering a two-speaker combo, could sell for $500 or more today, while a lower-wattage Checkmate 12 with a single speaker can be found in the $100 range. Yes, that's a tiny VU meter in the upper right corner.

Although the Teisco company is more famous for its electric guitars, the 25-watt Checkmate is no slouch. On its front panel, there are two instrument inputs with shared controls and a third input with its own volume control. The third channel is filtered for a bass-heavy sound. Volume, treble, and bass fill out the preamp dials. There's reverb and tremolo, with the latter having both speed and intensity controls. The back of the amp sports a speaker out and an extension speaker out. There are a couple of nice appointments on this head. A tremolo rate LED indicator monitors how fast the oscillator is moving. It also has the world's tiniest VU meter that provides an additional visual reference for how hard it's getting slammed. The VU is impossible to see from more than three feet away, but it's cool, nonetheless. Also, the amp is a featherweight. You can lift it pinky out like a steaming cup of tea. Teisco also made this amp with tubes in the mid-to-late '60s.

And the sound? Sweet! Its EQ, which is global, affects all three amp inputs and allows for nice variations in timbre. The treble is the most powerful of the two controls. The reverb is subtle, but does add depth and charm at higher settings. It's especially cool paired with the tremolo. Speaking of tremolo, as Jamie mentioned, that's where this amp shines. There's a beautiful sinusoidal wave shape to the oscillator, a wonderful intensity control, and a decent range of speed, so it covers a lot of ground—all the while staying in very musical territory, even when set to maximum speed. At higher intensity settings, with the reverb cranked, it really throbs as the reverb accentuates the tremolo, adding depth to the sound.

It's not a flamethrower, though. It's comfortable to listen to at maximum volume, but I fear it wouldn't hang with Ol' Brickfoot on the drums. A clean and appealing 3/4" shell frames the head. With a cabinet, the Checkmate 25 can go for about $500 and is a nice option to have in the studio.

Speaking of studios, let's bring in our other expert guest, Ben Vehorn, a product specialist and sales rep at EarthQuaker, and an experienced audio engineer. Ben knows a lot about gear, with studio equipment and modular synths among his favorites. He has yet to choose sides in the tubes-versus-transistors battle. Tasked with making music sound great, he just uses what works best in a given situation. His lack of bias toward either camp is his strength in the matter. So, let's see what he has to say.

The Roland Revo 250 was the studio flagship of the Revo product line, and, like its smaller 30 and 150 siblings, was one of the company's earliest attempts to create a spatial effect. These self-contained amp-plus-speakers units lack the subtlety of the Doppler and amplitude-modulation effects produced by a Leslie. They are also quite rare and can demand about $3,000 today. Note the classic early-Roland look of the control box.

Ben, what comes to mind when I say solid-state amps?

They are really cutting and have a kinda forward presence to the midrange—especially when blended with tube amps. Since tube amps have that kinda sag at a certain point, which sounds cool, solid-state is a nice compliment to that. If you start stacking too much of the same element in a mix, it gets lost, but if you double up parts with a slightly different sound, they become a nice foil for each other. I know we are talking guitar amps here, but for keyboard or synth amps, they are all pretty much solid-state these days. As far as voicings go, tube amps work with guitars, whereas synths sound more natural with solid-state.

Does a tube or a solid-state amp make you reach for a certain microphone over another?

I don't think so. I'd probably just use the same mics—maybe use a slightly darker mic for the solid state amp. But generally, I'd just use the same mics and maybe add some EQ later in the mix.

There's a solid-state amp that's one of my favorites ever: the Roland Revo 250. Its Roland's take on [an amplified] Leslie speaker. However, instead of an actual mechanical moving baffle/horn arrangement, it's got a giant 18" woofer that's down-firing. Then, for the horns, instead of rotating, it's got six smaller speakers. I think they are 8" inch speakers, and they are arranged in batches of two in a semicircle. It then electronically pans across them. So, you get less of the phase shifted part of the Doppler effect, but the volume part of it is a little more dramatic. There's also less whooshy mechanical noise. What it sounds like is more of a natural chorus. When you play it on the slow setting, in a room, it just fills up the environment. It sounds like the coolest chorus ever.

Let's digress from the conversation to peer behind the Revo's grille cloth. The Revo, which was debuted by Roland in 1975, came in 30, 125, and 250 designations. The 30 was the smallest—essentially a pair of bookshelf-sized speakers with a stereo amp and built-in chorus. The 250, favored by Ben, was the big daddy, with it's 18" downward driver and six 8" cones, electrically fired in sets of two, to approximate the Leslie's rotating horn setup. There's reverb, too! It's a tall cab, and formidable in weight, but not as much as a Leslie 145 rotating-speaker cabinet. The Revo has an accompanying foot controller reminiscent of the Roland AS-1 Sustainer or Roland/Boss CE-1 Chorus Ensemble. It's called the Revo Control Box RC-1. The input has a Hi/Lo sensitivity switch, and there's a piano or organ selector switch, plus four footswitches to control the cancel (bypass), slow, fast, and chorus functions.

And the sound? It's room-filling, with nice headroom that especially shines in the slower chorale modes. The 30, 150, and 250 models each have a different power output, speaker complement, and other features. One thing that really shines is the ramp of its oscillator. From chorus to flutter, there's a smooth ramp-in rate and an even more pronounced effect from full speed to slow or chorus.

But Wait, There's More

I thought of a few more amps that might be interesting to check out, including one that is on my repair bench as I write this article. It's an absolute monster and had me looking on eBay for era-correct parts to not only refurbish it to its intended sonic glory, but to build up the preamp, for my own tinkering. It's a Kustom 400B. Charles “Bud" Ross started building Kustom amps in the mid '60s. They are known for their unique look and sound, with their tuck and roll Naugahyde covering. All the models I've seen are solid-state, with various ones sporting bright switches, boost options, tremolo, and/or reverb. The Kustom amp line stands tall in my mind as some of the best sounding solid-state amps.

In the case of the Kustom 400B, there's 200 watts of clean and mean solid-state power when used in mono mode. And yeah, this amp model has selectable mono or stereo operation. It crosses over into the public address realm with its four channels, which can be mixed to one speaker output, or two preamps to one power amp section and two to the other. So it's like a PA mixer that can sum the input signals to mono or let you mix two channels to one speaker output and two others to another speaker output. Dope!

The preamps offer simple tone shaping, and the strongest tone-shaping option is the inputs themselves. Each of the four channels has high and low instrument inputs. The high seems to be tailored for full-frequency amplification. Plug a line-level-out synth into this input and enjoy the extended range it has to offer.

This is a lot of amp. Originally designed for use as a PA head, the Kustom 400B also quickly fell into the hands of bassists and guitarists. Separate power amps are share by channels 1 and 2, and 3 and 4. If you like dirt, but don't want to blow out Godzilla's hearing, you'll need some stompboxes. On the plus side, you can pick up a 400B for a couple hundred bucks.

The low input isn't just a gain-reduction option. It also offers a better interface for hi-impedance instruments. In other words, guitars. The amplitude and tone shaping controls are the tried and true combo of volume, treble, and bass. And they're responsive, offering a feeling of cut and boost in one control. There's no global master volume on this amp, so the volume is, well, the volume. There is also a bright switch option per channel. In the middle of the faceplate is the mono/stereo switch, for telling the output finals to work together or separately. On the rear of the amp, there are just simple speaker outs.

How does it sound? It rips! This Kustom is a back-wall blower-outer that's just frightfully loud, pummeling whatever cabinets are plugged into it. I was testing the stereo mode with a 2x12 cab with Celestion V30s plus a 15"-speaker Ampeg bass cab. The 2x12 was handling a majority of the output duties, and bringing in the Ampeg rounded out the low end to give it authority. Onstage, you might want to be on the side opposite of the bass player, since you'll be getting that “your guitar has more bass than my bass amp" look. The timbre is sweet and the attack immediate, with a nice chewy feel when hit hard with pedals or just a heavy picking hand. I'd love to tell you I dimed it, but I didn't for fear of hearing loss. It came across my repair bench because one side of its preamps just didn't sound right. It had been worked on before, and some under-spec parts were used for the repair. It also needed new power filters. It was a dream to work on. Each section of the amp, preamps, and power amps were on their own PCB—in almost a modular design. That made it easy to navigate and isolate problems in each section, rather than wrangle with a bunch of duplicated circuits all on one PCB. Thanks, Bud Ross!

Our final solid-state amp you oughta get to know is the amiably named Kasino Little Joe. And it's related to our Kustom. Bud Ross sold the Kustom brand to Baldwin in 1972, and Baldwin—best known for their pianos—continued to manufacture Kustom amps and introduced a new line called Kasino. These were similar to the Kustom line, but with different aesthetics. The tuck and roll look of the Kustoms was ditched for the safer and possibly more appealing look of standard Tolex. So if a player was searching for the Kustom sound, but didn't want an amp that looked like the back seat of a Cadillac, a Kasino was the ticket. Nonetheless, the Kasino line had its charms, with broad pinstripe grille cloth and recessed dials.

The Little Joe also has its volume, boasting an output rating of 125 watts. It has Hi and Lo instrument inputs, and a drive control allows tailoring the gain structure of the preamp. The standard controls are there: volume, bass, mid, and treble. The treble control also has a bright setting. And there are onboard effects, starting with tremolo and reverb. The tremolo has speed and depth controls, while the reverb has an intensity control that can be pulled up to a “high" reverb setting. Then, to really shape the timbre of the reverberation, they included a tone knob. That's cool!

At 125 watts, the Kasino Little Joe is bigger than its name implies. There's also an abundance of onboard effects, including boost, fuzz, tremolo, reverb, and gain—all of which makes this amp about as '70s cool as Starsky & Hutch. Also note the broad pinstriping on the cabinet's grille cloth and unusual porting in the back panel. These amps are currently selling for $650 to $800, depending on their condition.

Lastly, the Little Joe offers a boost option, with its own control, to get just the right amount of preset boost for every situation. Plus, there's a fuzz circuit in there with its own gain control, labeled “effect," and a level control to govern the output. With all those sonic options, this amp is a pedal company's nightmare! It's got all the essentials in one box. The rear of the amp sports a single speaker out, which was designed to be paired with a matching 4x12 cabinet with a slotted rear panel for focused, yet room-filling, sound. There are four footswitch jacks for controlling the various onboard effects.

And the upshot on its sound? Let's hear it from Karl Vorndran, part of the sales team at EarthQuaker Devices and the owner of the Kasino Little Joe that I investigated here. Karl: “The amp is loud, with lots of bass and mids. The built-in effects have a very '70s sound, which pairs well with the raw sound of the solid-state head. It's aggressive: perfect for thick, overdriven power chords and ripping fuzzed-out '70s riffs."

So those are our six contenders for transistor-amp glory. But, after contemplating my tubes verses solid-state biases, and getting a gander and earful of these transistorized beasts, here's what I think: There are tube amps and there are solid-state amps. Why not use both and choose each model for its individual strengths? Let's make transistors and tubes a uniter, instead of a divider!