Let me start with a story. When I was a kid, you could buy a Teisco Del Rey black-green sunburst guitar in the Sears catalog for $100. I remember clearly thinking that when they made the guitar, they had to get all the details right.

They had to buy the tuning pegs and install them; cut a nut; cut fret slots and fret the guitar; maybe put a truss rod in; carve the neck; make a body; finish the guitar (including spraying a sunburst); install a bridge, pickups, pickguard, and electronics; put strings on it; set the guitar up, and … oh yeah … include a case. What I thought at the time was, “Why don’t you just do it all well?” It wouldn’t be that much harder to do, and the instrument would be something you could play a concert on.

I also found out some time in the late ’80s that the market gives you permission for a product. By my definition, “permission from the market” means that, in general, the product is selling and customers are quite pleased with their purchase. I remember the tradeshow where Audio-Technica released the M50 headphone, and almost immediately it was given permission by the market. It is now an industry standard. Another good example from that period was that the market gave permission to ADATs (which were early digital recorders) and then took it away.

So, the question about gear and prices is: Are you getting your money’s worth? In other words, can you use the instrument at rehearsal, at a gig, in a concert, in a recording studio? I used the Teisco Del Rey as an example because, in a way, they were cool. The market gave permission to sell them, but I’ve never seen one used at a gig, a recording session, or a concert. If an instrument is not worth the money that is being charged, eventually the market will say “no,” and the instruments will be heavily discounted. So, there is a self-adjusting “Is it worth it?” process in the marketplace.

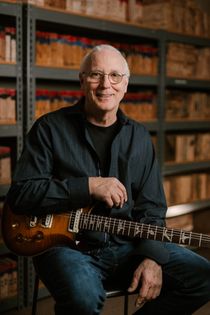

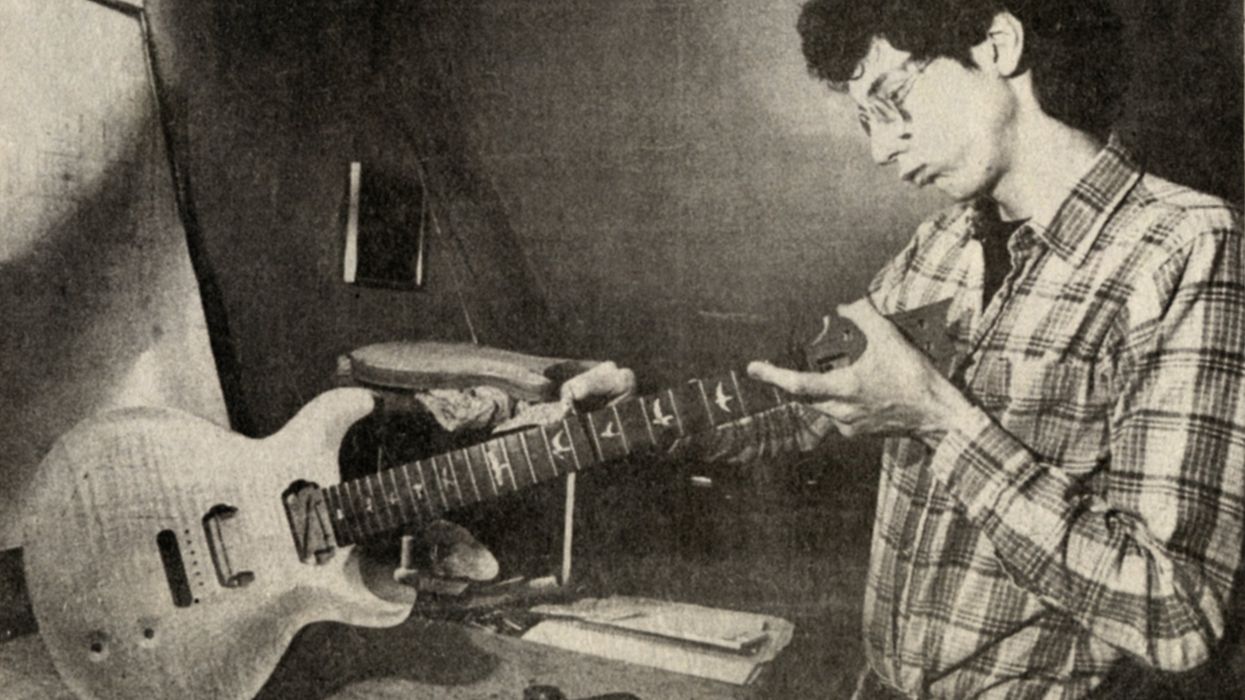

Paul Reed Smith holds court at a clinic.

In my world, whether it’s worth the money is really important. We build instruments that sell all the way from a MAP (minimum advertised price) of $499 to a MAP of $15,000 (which is still 1/20th the price of some vintage guitars). For me, it’s highly important that someone pick up an instrument and play it before they decide if it is “worth it.” When I am at clinics, I very often let someone in the audience play my personal guitar and ask if they like the way it plays and sounds. One of the things I like about buying guitars on the internet is that there’s almost always a return policy if you don’t like the instrument. It’s a safety net that I think is good for the customers in our guitar world.

“There only has to be one thing wrong with a guitar for it to not be usable.”

Another thing I like about the internet is that if you average the blur of all the comments and reviews on a model of instrument, you can get the beginnings of an idea of whether it is worth it. For me, I’m always looking for the product that people missed either in price or that the market never gave permission to.

I recently bought an untouched 1958 vintage Les Paul Special. What was interesting about it was the weight and the neck shape were perfect, but some of the notes were buzzing badly on the neck. We leveled the frets and were kind of taken aback because the frets had never been leveled out of the factory. What we realized is that we never held a vintage Les Paul before that a repairman had not worked on. Was the instrument worth the money the day it was sold in the 1950s? Yes. Was the instrument worth the money as a vintage guitar today? Yes. I got a good deal on an untouched vintage guitar, and it taught me a lot.

I don’t buy vintage guitars as collector’s items. I buy them to understand what the people who made them were thinking the day they were made. You can’t talk to the builders anymore, but the instrument will tell you what they thought. Was the instrument ready for a recording session or a concert when sold? No. So if I had bought it to play, it may not have been worth it to me. In that regard, playing the instrument and not counting purely on reputation are just as important as knowing your “why.” There only has to be one thing wrong with a guitar for it to not be usable. Let’s just exaggerate and say the third fret was in the wrong place…. Big problem. This is kind of the way I look at it.