Sgt. Pepper turned 50 in 2017. If he were American, he would have received his AARP invitation letter by now.

We know much about how the Beatles created the album, thanks to scores of illicitly released but widely available outtakes. But the outtakes included on this year's pricy “expanded edition" boxed set are particularly fascinating.

As most Beatles geeks know, Pepper was created on 4-track tape machines. They'd fill up one tape, mix it down to one or two tracks on another reel, and fill up the freed tracks with new parts. It was an awkward method that nonetheless produced great music.

But what if some of the music's magic didn't occur despite these primitive techniques, but because of them? Let's discuss what the newly released outtakes reveal.

They had a roadmap. The band and producer George Martin are famed for their studio experimentation. But the rough, first-take versions of these songs reveal that the team knew their destination before they rolled tape. The initial tracks leave abundant space for the parts to come, and the big picture is easy to perceive.

The drums don't drive. Unlike most rock recordings, where the drummer sets the pace and everyone else follows, Ringo plays sparsely, often letting Paul's keyboard define the feel. At times he stops drumming, or strips it down to minimal kick, tom, or hat. There aren't many fills, but when they do occur, they're the center of attention. Everyone else shuts up.

Also, the percussion parts vary over the course of a song—consistency be damned. Paul discussed this in a 2005 Drum! magazine interview with Robert Doerschuk: “On Beatles records you'd have a tambourine for a verse, then it would stop and a snare or something would take over.... I was always trying to do that in the '70s, but my producers would say, 'Just play the tambourine through the whole track and we'll work it out later.' And inevitably it would stay through the whole track. You'd have this record full of everything from A to Z—none of the instruments ever stopped. And that was boring."

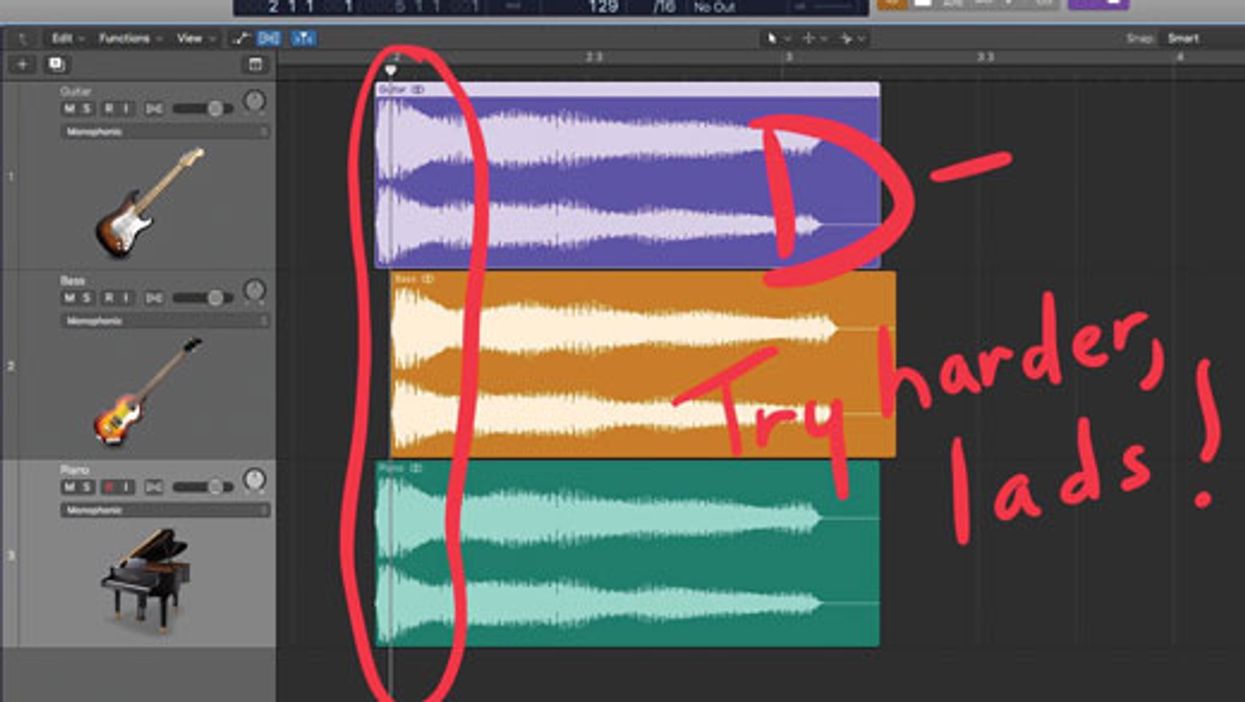

No track scrubbing. Nowadays it's common to scrutinize each track individually before mixing. We remove clams and background noise. We align downbeats to the grid. By modern standards, Beatles tracks are a bloody mess. But all that mattered was how a performance felt in context.

It doesn't help that our modern DAWs depict sound visually, so it's easy to fixate on parts that are “wrong" because they don't align to the grid. But the Beatles crew worked with their ears, not their eyes.

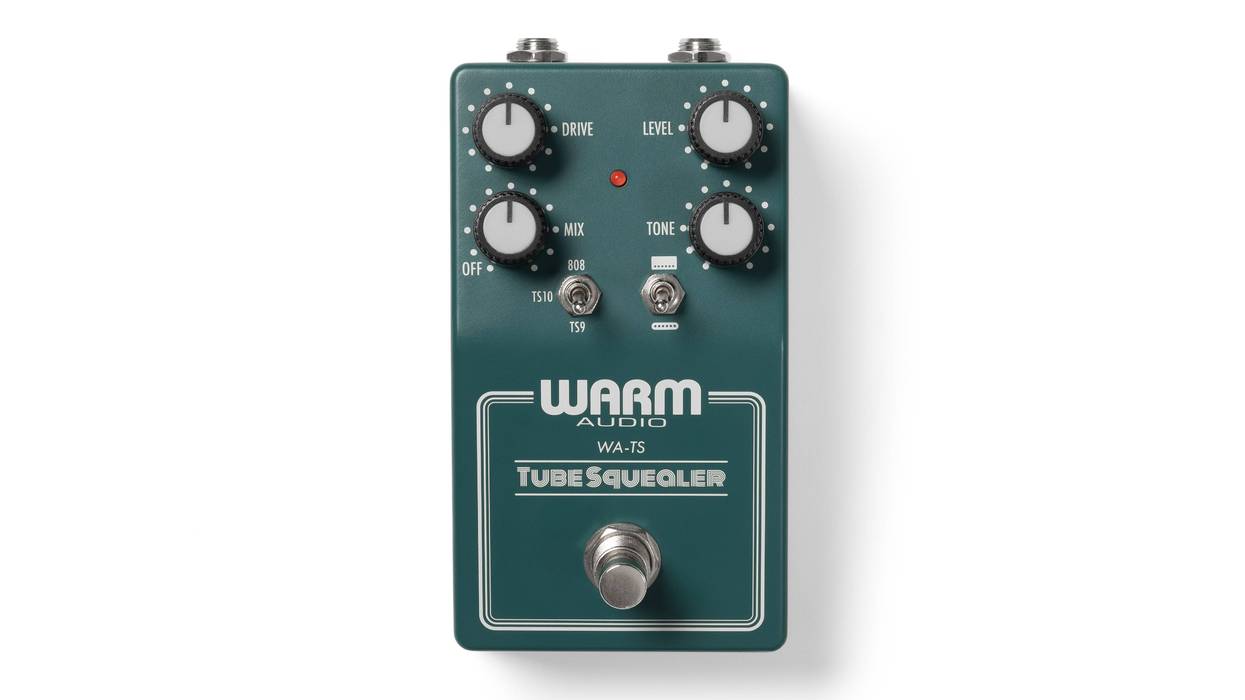

Ultimate tone. That's a silly concept. Sometimes it feels like we've had our ears and minds poisoned by YouTube videos, gear demos, and online debates about “ultimate tone." But only one thing determines a tone's quality: how it suits the musical context. There's no better example than Sgt. Pepper's laser-bright electric guitars. Few modern players would be caught dead issuing such strident treble squawks. But they're perfect for these dense compositions.

Frankly, many Pepper tracks sound lousy when soloed. Ringo's kick has little impact. (On the drum-heavy “Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise) [Take 8]," you hear Paul hectoring Ringo to stomp the kick harder.) John's acoustic guitar sounds boxy and flat in isolation. But in the midst of a dense track, it feels and sounds great.

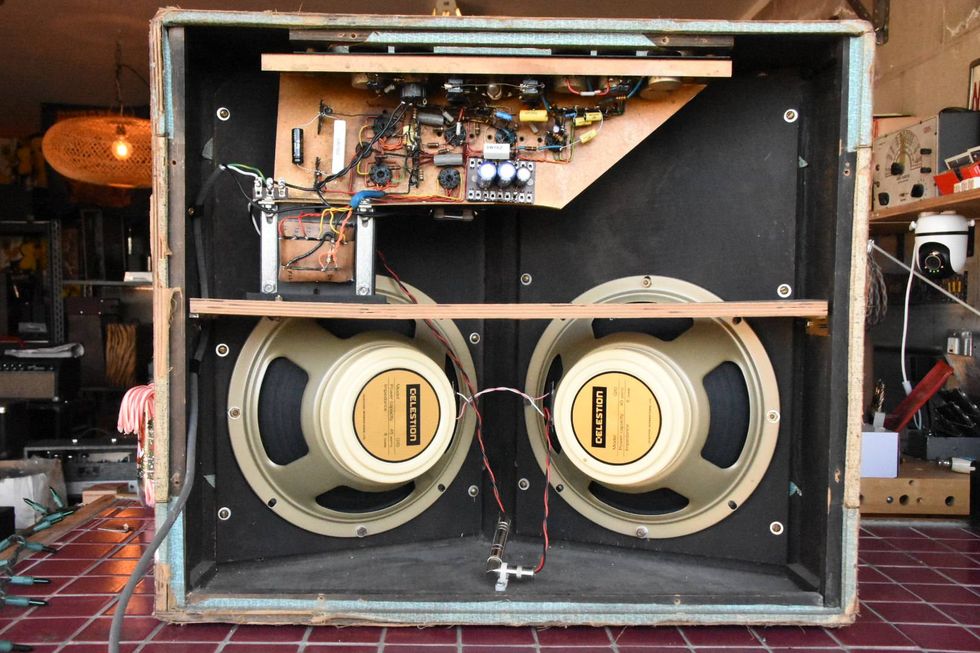

What matters most happens last. When you bounce tape, you lose high end and definition. While many modern rock records are built from the drums and bass up, Paul's bass was usually one of the last parts to be recorded. Sometimes drums were overdubbed as well.

Paul seems to be the most rhythmically definitive Beatle. In fact, his bass lines tighten the looseness of some initial tracks. When parts don't quite groove perfectly, it's often possible to add an overdub that triangulates between their feels, tying everything together. Paul's bass performs that trick over and over.

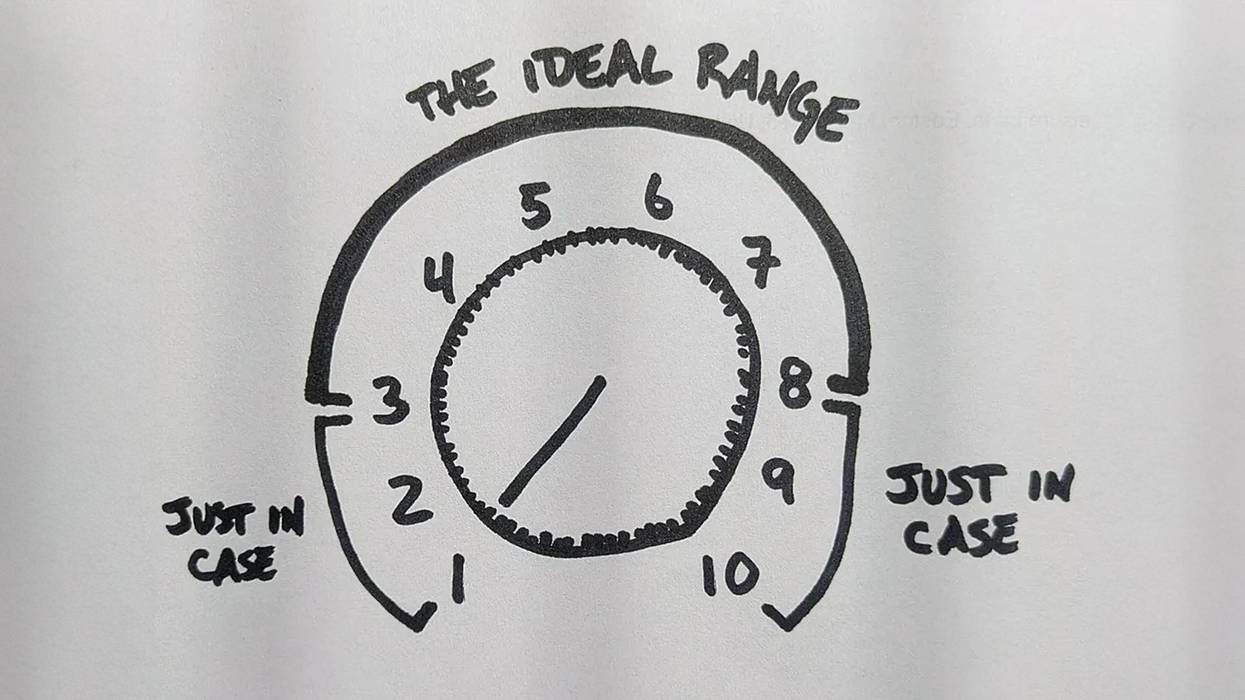

Space, the final frontier. Savvy musicians like to lecture about the importance of aerating your parts with silence, yet few today take the concept to Beatles extremes. In fact, many basic Sgt. Pepper tracks consist of little more than straight quarter notes, with the occasional open hat, guitar up-strum, or right-hand piano syncopation implying the swing. You know that Fadd9 guitar chord at the beginning of “Getting Better" that goes ching ching ching ching-a, ching ching-a ching ching? That's pretty much Sgt. Pepper's default groove. Funk, this ain't.

Burn the solo button! These observations share a common theme: The Beatles had their eyes on the final result, not the minute details of individual tracks. Nowadays we're addicted to the solo button. But since the Beatles crew was working with bounced tracks, they couldn't solo many of the parts even if they'd wanted to. It was about the forest, not the trees.

Few of us envy the travails of midcentury recording. It's nice being able to record 32 tracks on your phone! But it's worth pausing to consider the things we may have lost on our path to the present.