Although this singular stylist is based in country blues, his music reaches for the cosmos! Check out his dazzling array of pedals and rhythm boxes, and the classic instruments he uses to make trailblazing sounds live and on his new album, The Fatalist.

Buffalo Nichols believes in the power of acoustic country blues. He also believes it’s not a fossil, trapped in amber, but a living, breathing musical genre. Which is why he blends elements of the tradition—slide guitar, resonator, open tunings, themes of loss, redemption, and struggle—with loops, samples, drum machines, myriad effects, and modern-day narratives. His new album, The Fatalist, is the culmination of his art to date. Listening to its echoes of Skip James, John Hurt, Pink Floyd, and Dr. Dre is an even stranger experience when you know Nichols started his career in the thundering, downstroke-chiseled trenches of the Midwest metal scene.

When you watch this Rig Rundown, Nichols will explain, and play, it all—it's a fascinating story. And the gear! Get ready for a feast, full of the trad and the rad.

Brought to you by D'Addario: https://ddar.io/wykyk-rr

and D'Addario XS Strings: https://ddar.io/xs-rr

Adirondack Rose

Those two woods dominate this Recording King RO-328, with its solid Adirondack spruce top, solid rosewood back and sides, rosewood fretboard, and herringbone purfling in classic rosette. In fact, this guitar would not look out of place in a photo from the early ’50s, and the brand itself has been available since the ’30s. Nichols keeps this 6-string tuned to open C# minor, a Skip James tuning, with a Seymour Duncan Mac Mic pickup. His preferred sting gauge is .016 to .056.

Sweet 'n' Elite

Nichols’ parlor guitar is a Recording King Tonewood Reserve Elite Single 0, with a spruce top, rosewood back and sides, a mahogany neck, and an ebony fretboard. Note the inlays and distinctive binding. It also has the Duncan pickup system. Nichols keeps this guitar tuned in standard with a medium string set (.013s).

Steel and Gold

This Gold Tone GRS Paul Beard metal-body Resonator puts a brushed aluminum cone and biscuits inside an all-steel body with a 19-fret maple neck. With a stock lipstick pickup, Nichols uses it as one of his essential electrics. He prefers it to the more traditional thick resonator body, for ease of performance and weight relief.

Get Behind the Mule

Nichols’ tunings include C#m, open F, and standard, tuned down a half-step. This guitar is a Mavis model, by Mule Resophonic Guitars—an open tuning classic. Dig that pickguard and the warm patina on the body. “It’s taken on a life of its own,” says Nichols. “Some people will show up at my gigs just to look at it.” The mini humbucker sounds sweet, with its basic volume control. The neck isn't too thick or too thin. "Kind of in the middle,” Nichols says. And it mostly gets played clean, or with a nice flavoring of delay.

Banjo

The banjo is one of the oldest African-American instruments, and this one is a Recording King, with a scooped fretboard and two pickups (a K&K and a Fishman) that he sometimes uses to split the signal. Without a resonating back, Nichols notes that it caters more to old-school music, with its bright, ringing tone.

Travelin' Amp

These days Nichols’ road amp of choice is a Fender Tone Master Super Reverb. He likes the compression he gets from its four 10" speakers, as well as its back-saving weight. He also points out that he uses so many effects that his guitars sound the same regardless of his amp choices.

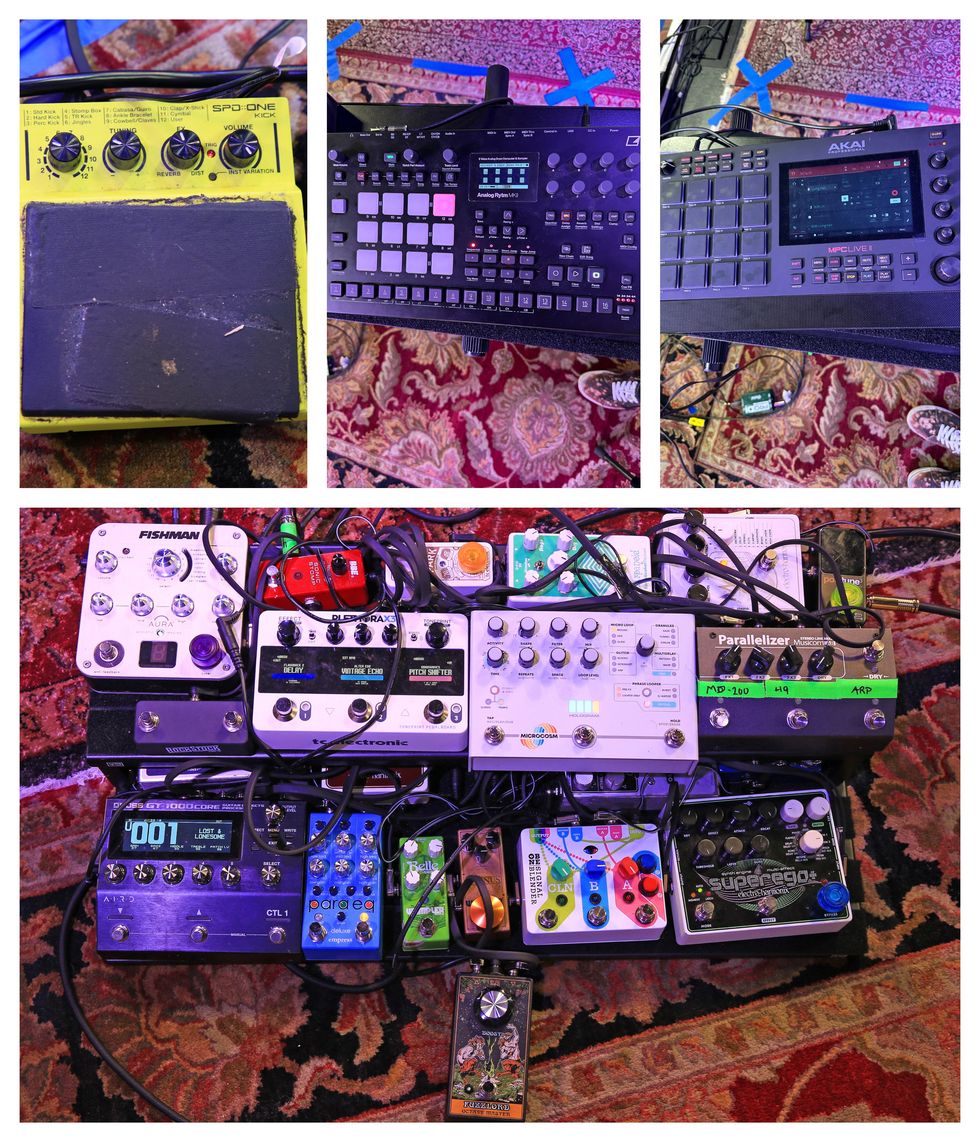

The Board's Big Brain

Nichols jokingly describes his pedalboard as "very confusing,” but, running through his chain, he starts at a TC Electronic PolyTune to an Origin Effects Cali76 compressor—"and after that’s where it gets pretty weird.” But also onboard, for drive, are a Wampler Tumnus and Belle, and a Fuzzlord Octave Master (“for my Jimi Hendrix kind of tones”). To control various effects and chains, there’s a Boss GT-1000 Core. Those are involved in the guitar-to-amp signal, versus the acoustic.

But the “weird stuff,” as he puts it, starts with an Old Blood Noise Endeavors Signal Blender for switching between the acoustic, banjo, or amp. While the Fuzzlord can color everything, a cluster of his boxes are used to conjure pads and other ethereal sounds. These include the EHX Superego, a Fishman Aura, a Hologram Electronics Microcosm Granular Looper and Glitch Pedal (he calls it his red herring), an EHX Mel9 Tape Replay Machine, a TC Electronic Death Rax3, and a lot more. Listen while Nichols displays his entire array of delays in the Rundown. There’s an SPD-ONE Kick for stomping, and drum machines—an Akai Professional MPC Live II and an Elektron Analog Rytm MKII—too!

Shop Buffalo Nichols' Rig

Recording King RO-328

Recording King Tonewood Reserve Elite Single 0

Recording King RK-R20 Banjo

Fender Tone Master Super Reverb

TC Electronic PolyTune

Origin Effects Cali76 Compressor

Wampler Tumnus

Wampler Belle

Boss GT-1000 Core

EHX Superego

Fishman Aura

EHX Mel9 Tape Replay Machine

SPD-ONE Kick

Akai Professional MPC Live II

Elektron Analog Rytm MKII

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)