PG’s John Bohlinger checks in with the guitarist/producer at the Nashville stop on his recent tour—to eyeball a bevy of classic-style Fender and Gibson 6-strings and his new, badass Two-Rock Bloomfield Drive amp.

When you produce acts like Taylor Swift, Fall Out Boy, Panic at the Disco, Weezer, Green Day, Pink, Rayland Baxter, Keith Urban, and Harry Connick Jr., it’s hard to find time for your own music. Yet in 2022, Butch Walker managed to release his 10th album, Butch Walker as … Glenn—a surprising tribute to the ’70s piano-rock balladeers that were among the rulers of FM radio in his youth. Nonetheless, that didn’t stop him from bringing a fleet of cool Fender and Gibson guitars, and a hemi of an amp, a Two-Rock Bloomfield Drive, on his recent It’s About Damn Tour tour.

For Walker, playing those guitars is something of a comeback celebration. In 2007, the house he was renting in Malibu from Flea of the Red Hot Chili Peppers caught fire and the Rome, Georgia, native lost the collection of classic axes he’d spent a lifetime accumulating, as well as the masters to every song of his own that he’d recorded. As Walker explains in the Rundown, it was a hard lesson about keeping up with insurance and making sure all his valuable instruments are covered—which they weren’t.

Today, he splits time in Nashville, where he’s also built a new version of his RubyRed studio in the old Warner Music building, from the 1950s. As Walker said in a Facebook post. “There’s been countless hits and amazing country and rock ’n’ roll songs recorded here over the years. It smells a little funny. It’s maybe haunted (hell, it was a morgue at one time). But I love it. It’s got vibe for days, sounds incredible, and people dig working here.”

So, dig into Walker’s Rig Rundown, which we filmed in November at Nashville’s Brooklyn Bowl.

Brought to you by D’Addario XS Strings.

Big Red

This Gibson ’61 reissue Custom Shop ES-335 with a Bigsby vibrato bridge, in wine red, was a gift from Gibson after most of Walker’s instruments were destroyed in the house fire. This guitar, and all of his electrics, stays strung with Ernie Ball .011 Slinkys.

Big Blue

Walker hand-painted this eye-catching Fender ’60s Custom Shop Telecaster, also with a Bigsby, blue with a floral-and-lightning-flash face.

Template Tele Classic

Here’s Walker’s all-stock Fender Custom Shop ’60s Telecaster Custom in a tobacco sunburst.

Give Gibson Some

This 2019 Gibson Explorer has a sonic secret weapon: a pair of 1970s DiMarzio Super Distortion pickups.

Rosy Tones

Another floral flourish: Walker’s live acoustic axe is a 2021 Gibson J-50 strung with an Ernie Ball Earthwood Medium Light set, .012–.054.

Old but Bold

It’s not every day you see a banjolin—not even in 1926, when Gibson built this one, just two years after the great guitar maker Lloyd Loar moved on from the company to begin early development of the concepts that would lead to electric guitar.

To Rock a Two-Rock

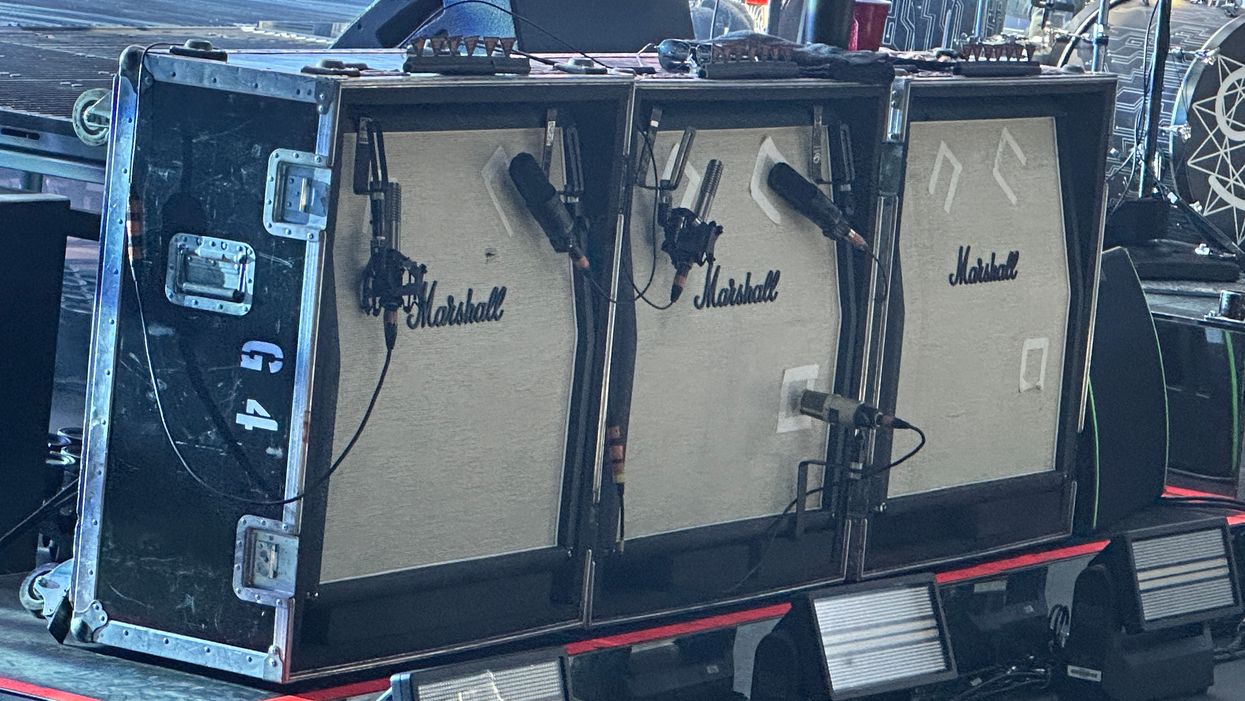

Walker runs his Two-Rock Bloomfield Drive into one of the company’s 2x12 open-back cabinets for his stage sound, but his guitar’s signal is fed into a Universal Audio Ox Box for extra tone sculpting. A Paul Reed Smith HDRX 20 come along as a backup.

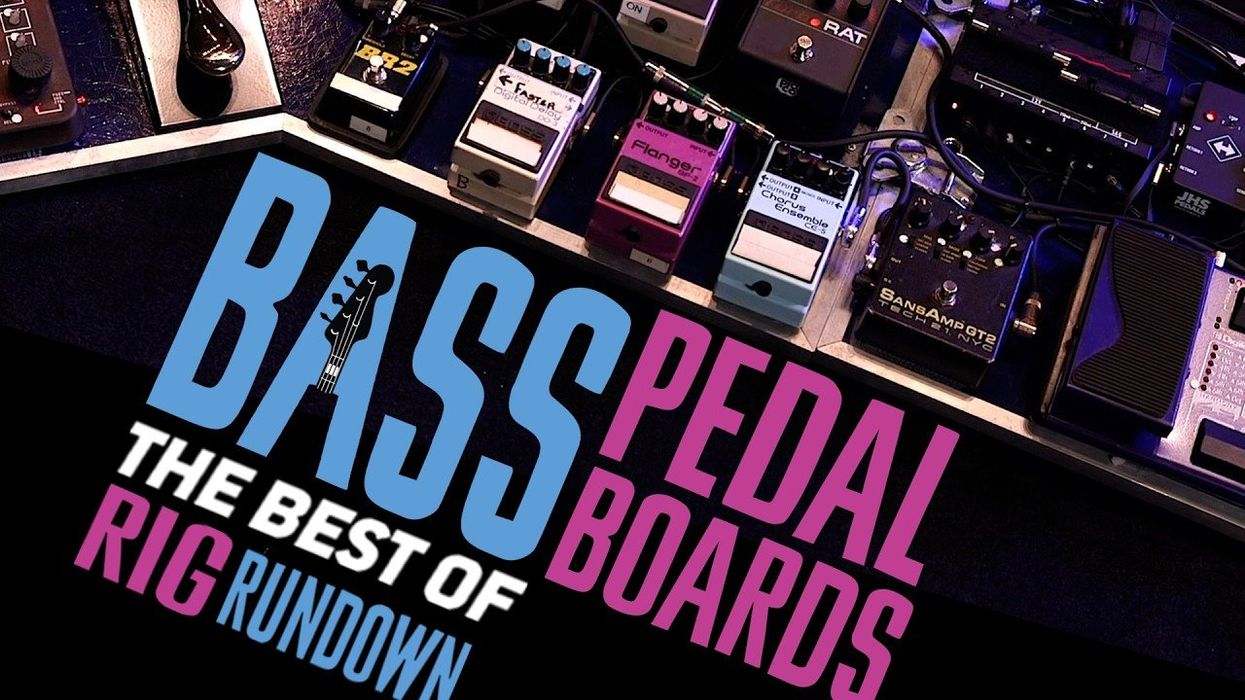

Butch Walker’s Pedalboard

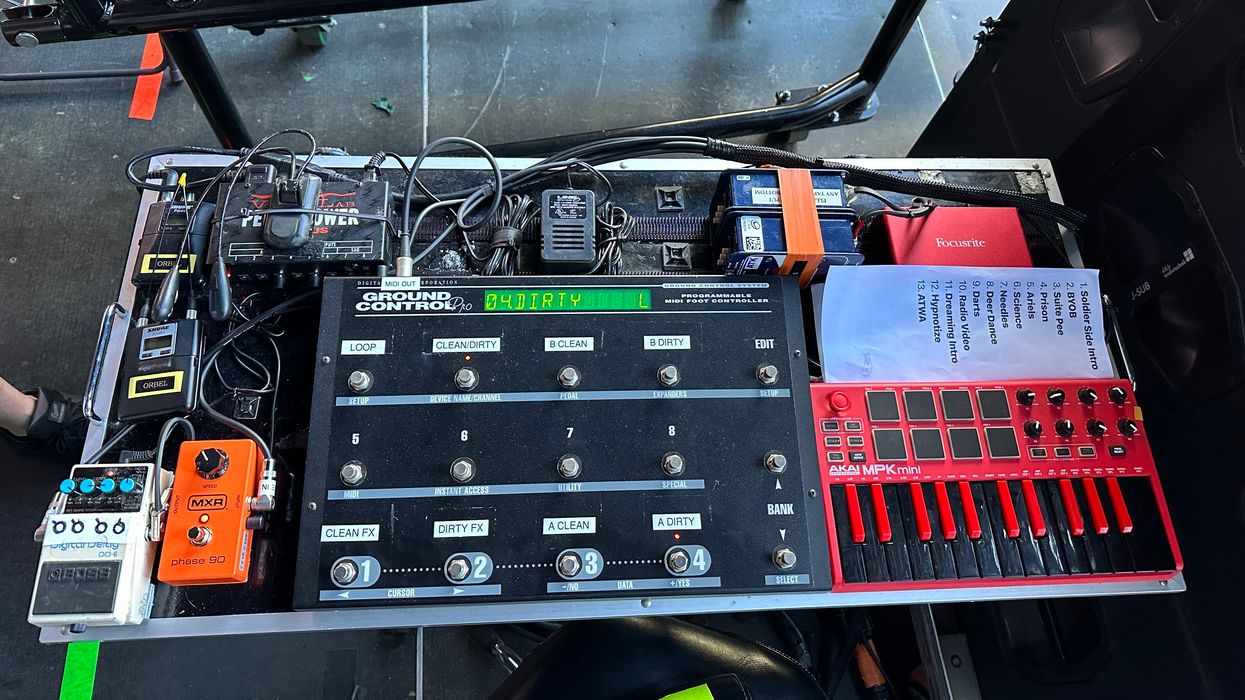

Actually, they’re Walker’s, and he reaches them via a Line 6 G90 wireless. From there, it’s a Boss TU-2 Chromatic Tuner, JHS Pulp N Peel compressor, his JHS ЯR signature overdrive, a Way Huge Conspiracy Theory OD, an MXR M249 Super Badass, MXR M300 reverb, UAFX Starlight Echo Station delay and Astra Modulation Machine, and a ToneDexter acoustic DI/preamp/wave mapping (similar to IR technology) pedal. Under the hood is a CIOKS DC10 for power.

![Rig Rundown: Butch Walker [2022]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/rig-rundown-butch-walker-2022.jpg?id=32346186&width=1200&height=675)

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)