Witness drone metal overlords Stephen O’Malley and Greg Anderson pack and rattle a cave with two guitars, 14 amps, 16 cabinets, and 19 pedals to test the Earth’s crust.

We’ve featured loud rigs. We’ve stood strong in front of Matt Pike’s octet of Oranges, been washed over with waves of volume from Angus Young’s nine Marshalls for AC/DC’s “small gig setup” in an arena, trembled from J Mascis’ three plexi full stacks, and even withstood Bonamassa’s barrage of seven amps at the Ryman, but nothing prepared us or compared to the Godzilla-rising-from-the-Pacific roar that is Sunn O)))’s auditory artillery. And it’s more than the sheer sight of 14 amps and 16 cabs or the dishing of deafening decibels; it’s the interplay of these characters and their conductors.

“The third member of the band is the amplifiers!” laughed Greg Anderson in a 2014 interview with PG. “We use vintage Sunn Model Ts from the early ’70s. They’re a crucial part of the show. I’ve got more amps than I have guitars.”

Stephen O’Malley takes a more metaphysical outlook to the connection between him and the thundering Model Ts. “My philosophy is that I’m just part of this bigger circuit of the instrumentation,” he says. “You have, of course, the amplifier valves, the speaker, effects pedals acting like different and various voltage filters, the air in the room, and the feedback generated from all this equipment, so who’s in the band is immaterial.”

We learned more about O’Malley’s perspective when, following a 90-minute drive southeast from Nashville to Pelham, Tennessee, and a short descent into The Caverns, the Sunn O))) guitar tag team welcomed PG’s Chris Kies onstage for an amplifying chat. O’Malley details his signature Travis Bean Designs SOMA 1000A, while Anderson explains how a broken guitar led him to his beloved Les Paul goldtop. Both pay homage and reverence to the eight Sunn Model Ts that form the band’s foundational tonal force, and explain why the LM308-chip Rat influenced their Life Pedal collaboration with EarthQuaker Devices.

Special Silver 25th anniversary edition of the V.3 Life Pedal

Sunn O)) Official Website

Brought to you by D’Addario XPND Pedalboard.

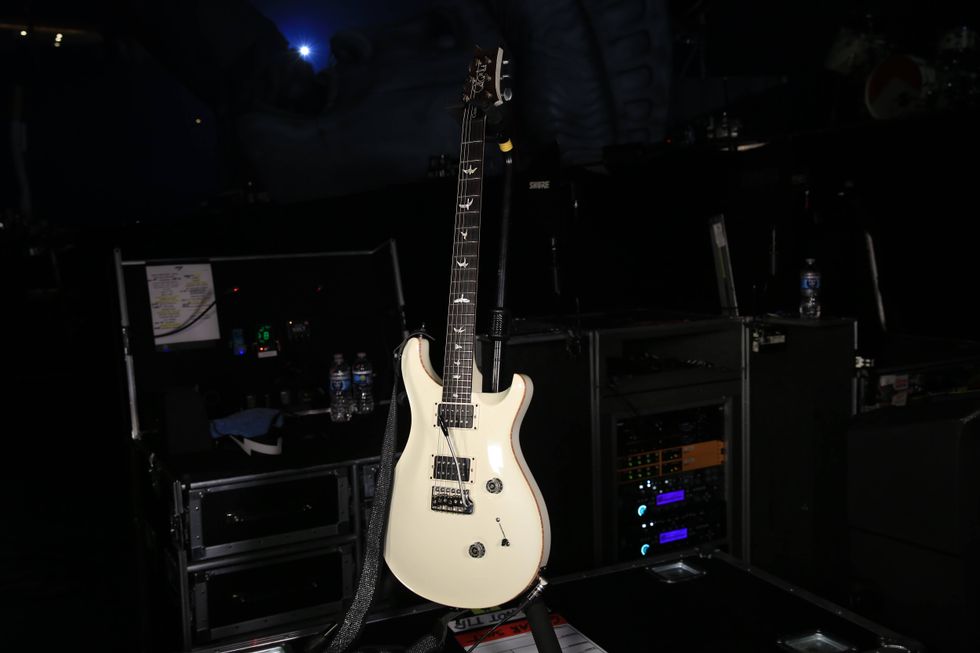

Silverburst Slugger

This is Stephen O’Malley’s signature Travis Bean Designs SOMA 1000A that he co-designed alongside Electrical Guitar Company’s Kevin Burkett and late luthier Travis Bean’s wife, Rita Bean. Burkett revitalized the brand in the early 2010s with the guidance of Rita and Travis’ longtime business partner Marc McElwee.

First off, just like the original TB models, these feature a single piece of 7075-T651 aluminum alloy that runs the length of the guitar’s backside that makes up the headstock, neck, and the rear half of the body. Its scale length is 25.5", the neck radius is 12", and it has a brass nut set for the band’s use of A tuning. The handwound high-gain TB humbuckers are built to Stephen’s specs. The build includes CTS pots, Sprague caps, and Switchcraft hardware. The silverburst finish covers a koa body.

Stephen’s thoughts on the collaboration: “Being honored with a signature model is great, but the bigger achievement or accomplishment is having an interaction with Kevin and the Bean family, who produced an instrument we’re all proud of.”

Strong T

Here’s the standard eye-catching T headstock and brass nut featured on all old and new Travis Bean instruments.

Stephen’s Specter

This transparent devil is an Electrical Guitar Company Ghost that has a 1-piece aluminum neck that covers backup duties for O’Malley. Fun fact: this has the same pickups in it as Steve Albini’s high-output single-coils in his Travis Bean Designs TB500 signature. They are RWRP (reverse-wound, reverse-polarity) to reduce the 60-cycle hum.

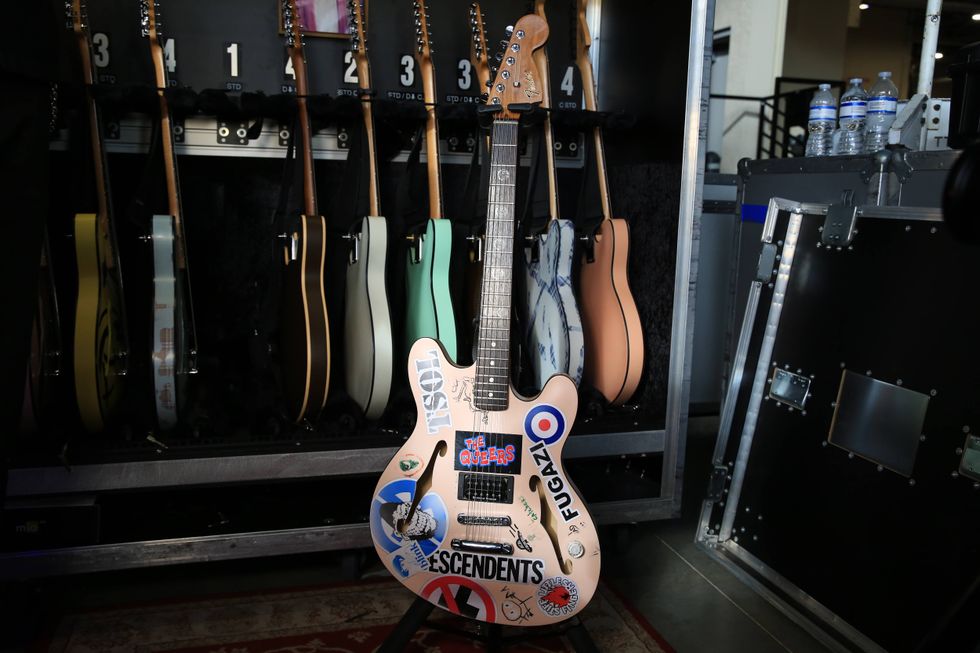

Greg’s Lucky Goldtop

While touring with Boris in 2008 or ’09, Greg’s main 1989 Gibson Les Paul goldtop endured a neck fracture. On their next day off, he wandered into the nearest Guitar Center and walked out with the above 2005 Gibson Les Paul Deluxe. It originally had mini humbuckers, but Anderson felt they were “thin-sounding.” So, he swapped them out for a set of DiMarzio P90 Super Distortions, that are actually humbuckers housed in P-90 enclosures for replacements that don’t require routing. He loves the violent output and grind provided by the P90 Super Distortions.

Sonic Protagonists

“The amps are certainly the main characters of the band,” concedes O’Malley. The main protagonists for Sunn O)))’s sonic saga are the eight Sunn Model T heads they set onstage. (Six are on and plugged into, while each member has a dedicated backup.) Stephen mentions in the Rundown that he prefers lower-wattage speakers, but when requesting backlines or renting gear from SIR, they can’t be too picky with the vast amount of cabinets they need. O’Malley runs his Model Ts and ’80s Ampeg MTI SVT through either 4x12s from Sound City or Fryette. The silver-panel Ampeg SVT-VRs flanking both ends of the semi-circle, are being slaved by each member’s MTI SVT, and that signal is hitting their matching Ampeg Heritage SVT-810AV cabinets outfitted with 10" Eminence drivers.

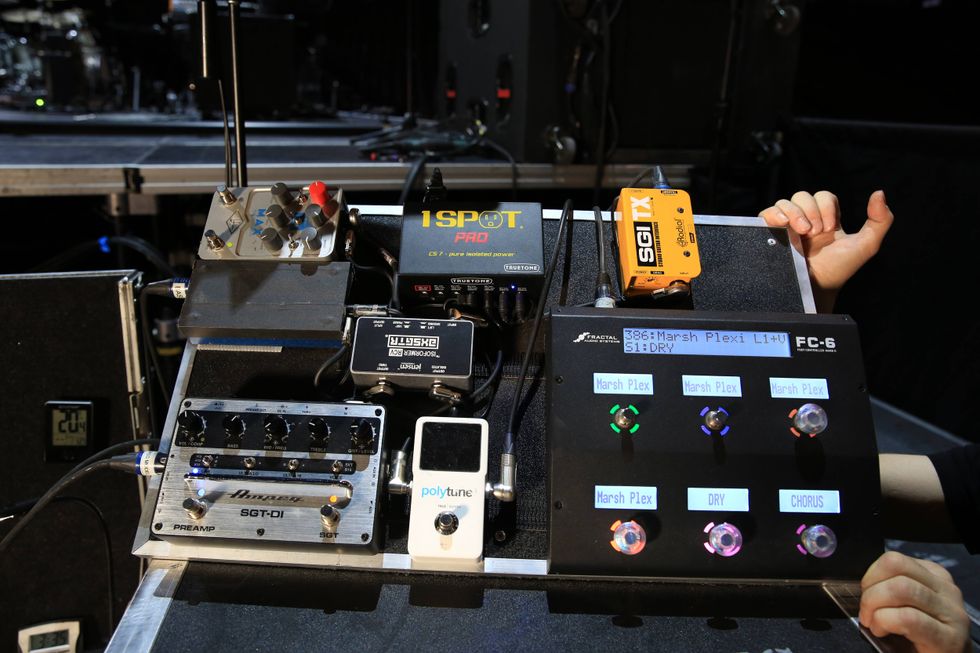

Stephen O’Malley’s Pedalboard

“My concept in playing this music for tone involves many, many, many different gain stages that are all intonated differently depending on the pitch of the sound. There are slight shades of color saturation or grain as if it’s a paint—the shorter bandwidth color gradation or the density of the paint.” All these subtle sweeps of saturation, sustain, and feedback are enlivened and exaggerated with Stephen’s pedal palette. His current collection of slaughtering stomps include the band’s most recent collaboration with EarthQuaker Devices (Life Pedal V3), an Ace Tone FM-3 Fuzz Master, a Pete Cornish G-2, and an EarthQuaker Devices Black Ash. For subtler shadings, he has a J. Rockett Audio Designs Archer.

The EQD Swiss Things creates effects loops to engage the FM-3, G-2, or the Black Ash. In addition, he runs a Roland RE-201 Space Echo through the Swiss Things, too. O’Malley uses the Aguilar Octamizer as a “fun punctuation that comes on once in a while. It abstracts the guitar into minimalist electronics [laughs].” The custom Bright Onion Pedals switcher keeps the amps in sync with phase controls and ground lifts. A Peterson StroboStomp HD keeps his Travis Bean in check. Off to the side of the board is a Keeley-modded Rat that initiated the band’s core sound, plus a Lehle Mono Volume. (Stephen is a Lehle endorsee.) This circuit includes the heralded LM308 chip and was the basis for their partnership with EQD and the Life Pedal series.

Space and Time

Elevated off the stage floor and secured by a stand are O’Malley’s Roland RE-201 Space Echo and Oto Machines BAM Space Generator Reverb.

Greg Anderson’s Pedalboard

“To be honest with you, I try to keep it pretty simple now because I love pedals and have fallen down a lot of rabbit holes with them, but I found myself troubleshooting and having more issues than my sound warranted. When I started with this band, it was just a Rat and tuner pedal, so I try to just bring what I need,” says Anderson. He found a potent pairing with the EQD Life Pedal V2 acting as a boost and running into a vintage Electro-Harmonix Sovtek Civil War Big Muff that creates a “powerful, chewy, ooze” tone. Like O’Malley, he also has a custom Bright Onion Pedals box and an Aguilar Octamizer set to unleash a “ridiculous, beating, fighting, chaotic, sub-bass sound.” An Ernie Ball VP Junior handles dynamics, a Boss TU-2 Chromatic Tuner keeps his goldtop in shape, and an MXR Mini Iso-Brick powers his pedals.

![Rig Rundown: John 5 [2026]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62681883&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C45%2C0%2C45)