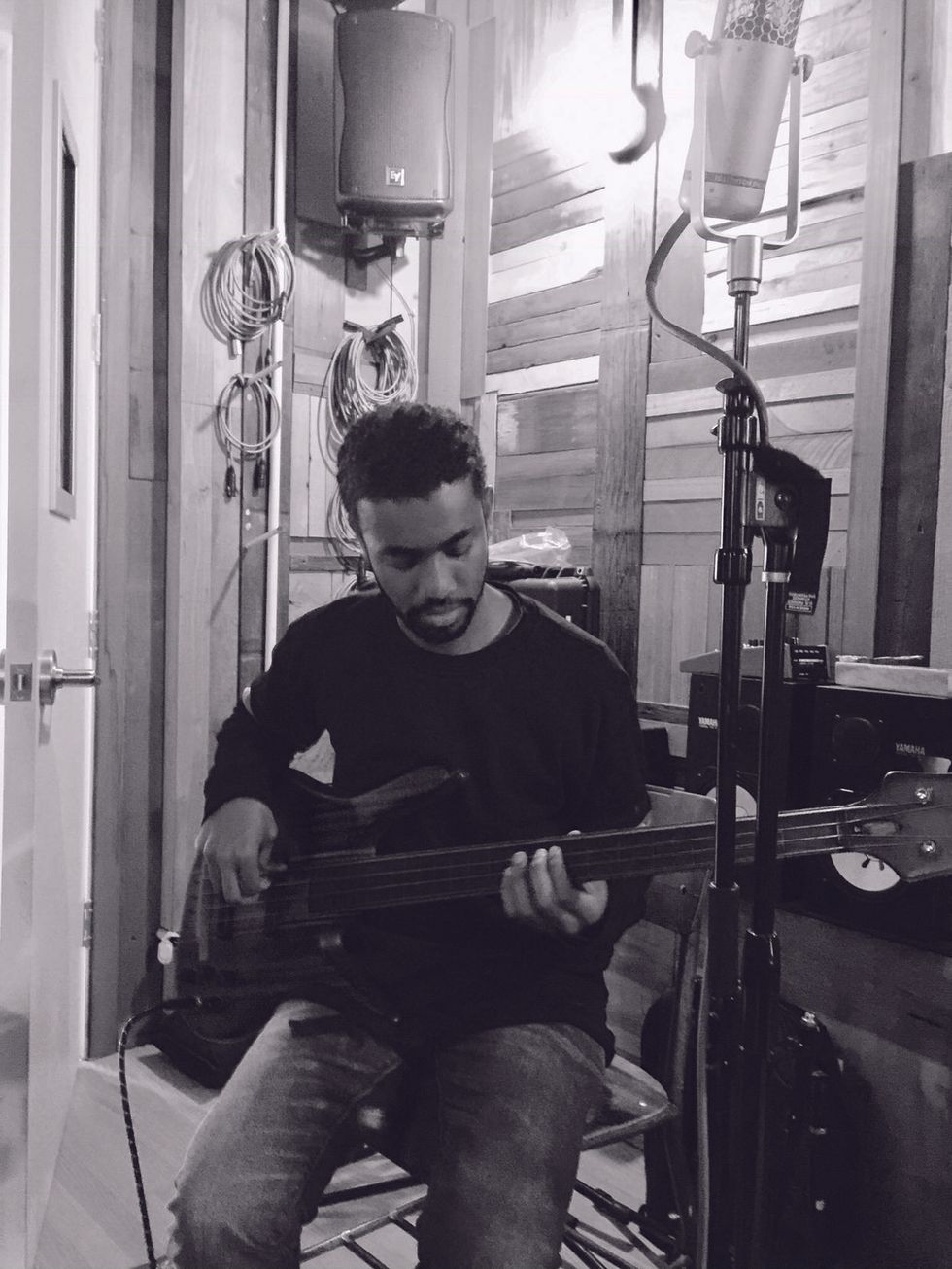

Joshua Crumbly says that a lot of his musical ideas start out reflectively, like a mantra or meditation, often repeated over and over as he develops them. It’s a Zen-like practice that allows him to access a deeper, more intuitive headspace. “All of the songs that made ForEver, they kind of took my mind and heart somewhere as I played them,” he says of his new album. “And there was so much going on in the world during the pandemic, I just feel like the storylines came to fruition.”

The inventive bassist was born and raised in Los Angeles and attended the prestigious Juilliard School in New York City. When we spoke, he was in Dallas, Texas, co-producing and writing an album for Brandon Marcel. Crumbly and Marcel both tour in R&B singer Leon Bridges’ band. Marcel is one of the background vocalists.

“We were engaged in writing for three or four days last week,” says Crumbly. “And then yesterday we had to do a streaming show with Leon Bridges.” Apparently, the guys in Bridges’ band have been making fun of Crumbly because he’s always bouncing between New York and Los Angeles and can’t decide where to put down some roots. “I keep telling them, ‘I’m finally going to officially move back to L.A. permanently.’ So, they’re like, ‘Yeah, right.’ And now I’ve been in Dallas for a couple of weeks and I’m like, ‘Oh man, I’m loving Dallas.’ I’ll figure it out. The grass is always greener, right?”

Joshua Crumbly - The See (Official Music Video)

Crumbly’s debut 2020 release Rise, embraced that concept wholeheartedly. “I’m initially coming from different jazz settings, and I’ve gotten to play with some brilliant people over the past 11 years or so,” he explains. “But [with jazz] I just got to a point where I was like, ‘Man, we have all these brilliant minds, and everybody’s writing songs with the same exact form, and every song has the same experience for the musicians as well as the audience.’ So I was like, ‘I want to see if there’s a way to create songs that have a different journey to them.’”

This songwriting journey continues on ForEver. Stylistically, like Rise, the tunes on ForEver aren’t necessarily jazz. They run the gamut from indie rock (“THREE”) to ambient (“ForEver”) to the Motown-infused thump of his playing on “C.S.C.” Crumbly mostly eschews the traditional jazz arrangements that primarily defined his formative years as a bass player and sideman. Take a song like “Reflection.” Grounded by a hypnotic bass ostinato, it upends jazz norms by introducing the melody at the end of the tune, as opposed to playing the melody first, then a bunch of solos, and then the melody out, as in a conventional post-bop arrangement. If Crumbly’s ambition was to construct songs in such a way as to give everyone involved a new experience, on ForEver he unequivocally succeeds.

“Shout out to Universal Audio for changing my life. And believe it or not, I use GarageBand.”

Born in 1991, Crumbly began to study music at an early age, at the behest of his father, saxophonist Ronnie Crumbly. He started out playing classical piano before picking up the bass at age 9. He learned to play by ear in church, and then dove into heavy metal at the local music store, where he subsequently took lessons, before binging on the jazz records at home that would become his muse. Though Crumbly studied with such venerable jazz stalwarts as Ron Carter and Reggie Hamilton, there’s a pop element to his songwriting that makes his recordings eminently welcoming for the average listener. His fascination with pop songs, as a writer, can be attributed to what he calls “commercial sentiment.”

“What I think is actually cool about popular music, is the power of a song is still prevalent, and it doesn’t always hinge on a million solos and that sort of thing—just a melody and a vibe, with no solos or anything like that.”French playwright Antonin Artaud once made the provocative assertion, in his seminal 1938 theatrical treatise, The Theatre and Its Double, that the actor is “an athlete of the emotions.” Likewise, Crumbly doesn’t knock you out with chops on ForEver. Instead, he tugs at your heart with an empathic vibe that comes across in his songwriting as well as his bass playing. Instead of rapid-fire slapping or lightning-fast finger tapping, Crumbly’s virtuosity on ForEver lies within his ability to convey qualities like fragility and tenderness. His performances often affirm the age-old adage that it’s not always about what you play, but how you play it.

TIDBIT: Crumbly’s latest release was started at Brooklyn’s Figure 8 Recording studio, but he finished the album at home on GarageBand, using hardware and plug-ins from Universal Audio and Arturia.

“I’ll give you some insight to the song ‘Reflection,’” he offers. “I wrote it during the time when the tremendously sad George Floyd incident occurred, and that was coinciding with rising Covid cases. The news would go between speaking about George Floyd and then reporting on all these deaths around the world from Covid. So, I started accompanying the news with the ostinato that the song is based on, and just reflecting on what the feeling of the time was. But then, the more I played it, I started becoming more hopeful. That’s how that song came about—just regarding what I might have been thinking about at the time.”

The catalyst for recording ForEver was an unexpected call from Figure 8 Recording’s Shahzad Ismaily. “I didn’t have his number saved in my phone,” recalls Crumbly, “so I had no idea who it was. And he said, ‘Josh, you need to record a solo bass album.’ And I was like, ‘Uh, okay.’ He generously offered me some time at his beautiful studio, Figure 8, in Brooklyn. I started ‘THREE’ there, and then also ‘We’ll Be (Good).’ But then I just got super busy with putting out Rise, and constantly being on the road, so ForEver had to get shelved. And then, when the pandemic happened, I got a bunch of recording gear and was able to devote time at home to finishing ForEver. So, shout out to Universal Audio for changing my life. And believe it or not, I use GarageBand.”

Joshua Crumbly’s Gear

Crumbly, always in search of unfamiliar sounds, plays flatwounds on his Michael Tobias Design Kingston bass. He also enjoyed “testing the limits of what a P bass could do” while making ForEver.

Photo by Ronnie Crumbly

Basses

- Fender American Special Precision Bass

- Michael Tobias Design Kingston (4-string)

- Moon Guitars J Bass

Amps

- Ampeg SVT (with 4x10, 6x10, or 8x10 SVT cab)

Strings & Picks

- La Bella Deep Talkin’ Bass flatwounds (.049–.105)

- Labella Custom Nickel (.050–.105)

- Fender Classic Celluloid medium picks

Effects

- Aguilar Octamizer

- Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi

- MXR Phase 90 M101

- Universal Audio Golden Reverberator

- Universal Audio Starlight Echo Station Delay

Recording Gear

- Arturia interfaces and plug-ins

- GarageBand for Mac

- Universal Audio hardware and plug-ins

Most of the effects heard on ForEver are delay modulators. “I messed with a lot of the Universal Audio plug-ins, and I’m really happy that they came out with physical renditions of those plug-ins in the form of actual pedals,” admits Crumbly. “I’ve been able to recreate some of the sounds live. I did use some pedals at Shahzad’s studio that I don’t even remember the names of, but I would say 80 percent of it is different delay modulators from UA, and the song ‘To Morrow’ is a combination of modulators and fuzz pedals. That was the one song on the record that I had to work on for a few days. I was searching for this particular sound in my head, for that melody line.”

There’s a cinematic quality to the music on ForEver that Crumbly’s tasteful use of effects enhances, each song characterized by a distinct mood or atmosphere. “When I had an idea, and then found the effects that were speaking to me for that song, I think it definitely took me somewhere, gave me this experience, and brought meaning to the song. It amplified the whole experience.”

As a jazz-based musician, Joshua Crumbly takes a road less traveled, through pop, rock, and ambient music, to get to his signature approach.

Photo by Giraffe Studios

As for instruments, Crumbly says there’s “a lot of 4-string P bass” on ForEver. “I bought a 2012 Fender American Special Precision Bass that I found, all beat up, at Chicago Music Exchange,” he remembers. “When I brought it to soundcheck, everyone was like, ‘Oh my God, it sounds amazing.’ So, I put away all the other 5-string basses that I had. It was fun, testing the limits of what a P bass could do on this record.” On the ambient title track, however, Crumbly went back to what he considers his first real instrument: an MTD Kingston bass. “It’s actually a passive instrument,” he clarifies. “I switched things up a little bit. I hadn’t ever seen anyone using flatwounds on an MTD. So that’s what’s on there now.”

“‘I want to see if there’s a way to create songs that have a different journey to them.”

Songs like “Reflection” and “We’ll Be (Good)” are crafted around chords and double-stops for the central bass line, and Crumbly says his technique for that kind of approach is “the thumb, and then my index and middle finger.” However, he is not a fingerstyle purist, as demonstrated in the video for “The See,” in which he plays an astronaut. “I’m playing with the pick, and I have to shout out a mentor of mine named Reggie Hamilton. I would not be playing upright bass if it weren’t for him, nor would I be playing with the pick. I owe a lot to him for broadening my horizons. People are sleeping on how cool playing with a pick is on the bass, but I’m okay with that. I’ll be like, ‘All right, I’ll be one of the few, I guess.’”

Space is the place: Joshua Crumbly donned an astronaut costume for the video for “The See," from his new album.

Photo by Ronnie Crumbly

As for his time at Juilliard, Crumbly says “keeping a vision” was one of the most important things he learned at the school. “I think keeping a vision helps you get through a lot of things that may be tough at the time,” he explains. “College was a bittersweet experience, because I was juggling being on the road with [trumpeter] Terence Blanchard and being in school full time. And a lot of the administration wasn’t cool with that, but I had a dream job that I couldn’t say no to, and it was a dream for my parents that I went to college and finished. They weren’t so sure that I was able to do both, but when you have a vision, though, you’re looking ahead. It also makes the present moment sweeter at the same time. I also learned how to be more disciplined, studying with Ron Carter, getting to see how on point he is, and what a master he is, and the level that he expects of his students. He just believes in you infinitely. I think we should all believe in ourselves in that way, too.”

Ultimately, Crumbly says that making ForEver was a “crazy adventure” that allowed him to explore the bass in a new way. “I feel like I’m on a path that I can explore infinitely by way of the bass and by way of emotion as well,” he explains. “I just hope that my music is very inviting to whatever people may like. You don’t have to be a jazz head or a rock head or whatever. I just want it to be a super-inviting, welcoming sound.”

Listen to Joshua Crumbly and his ensemble—saxist Josh Johnson, pianist Ruslan Sirota, and drummer Jason Burger—shape jazz in their own free-ranging, ambient image while performing “Noah,” from 2020’s Rise, at the now-shuttered Los Angeles jazz mecca the Blue Whale.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.