On his new album Thisness, Miles Okazaki is credited as playing guitar, voice, and robots. If you imagine that the reference to robots is some sort of artsy kitsch—like trapping a Roomba Robot Vacuum into a tight space to sample its struggles as it percussively barrels into the four walls—you’re very far off the mark. Okazaki—who has an elite academic pedigree with degrees from Harvard, Manhattan School of Music, and Julliard, and currently holds a faculty position at Princeton University (after leaving a post at the University of Michigan, to which he commuted weekly from his home in Brooklyn for eight years)—wasn’t kidding.

“The robots are machines that I made in Max/MSP,” clarifies Okazaki. (Max/MSP is visual programming language for music and multimedia.) “It’s kind of a long story, but I’ve been doing this stuff on the side for 20 years or so. Some of the music theory, some of the conceptual stuff involved in the album, I programmed into these things that I built. These improvising machines can do things that humans can’t do. They’ll play faster than humans, but they’ll fit in because they’re playing the same type of material.”

I'll Build a World, by Miles Okazaki

Okazaki explains that he creates parameters for the robots to improvise within: “I’m just telling this robot, ‘Play at this tempo and play this many subdivisions per beat—eight subdivisions or something like that—so that it’s linked up with the drums.” For pitches, he assigns a scale and can control the phrasing. “I’m saying for the pitch choices, ‘You’re going to use a chromatic scale and you’re going to play each note of that scale until you exhaust the scale without repeating a note,’ which makes a 12-tone row. It could be any scale, but that’s one of the settings that I have made in there. [After each 12-tone row is done] I tell it, ‘You’re going to take a little break, but I don’t want it to be the same break every time,’ so that it’s a phrase.”

To get a sound that convincingly blended in with the rest of the tracks, Okazaki had keyboardist Matt Mitchell run the robots through his Prophet Six analog synth. “I wrote a file of them improvising and ran that file through the synth,” explains Okazaki. “Matt would do the sounds for it,” so both the robots and Mitchell used the same Prophet Six in their own way.

“I’ve never been that interested in imitating anybody’s style.”

Okazaki, a family man with three children, seems busy in all parts of his life, but he must have learned to maximize his time because he’s incredibly productive. In 2018, he recorded his magnum opus, the critically acclaimed Work—a five-hour, 70-song marathon of the complete works of Thelonious Monk, all performed on solo guitar. It’s a project he’s wanted to do since his teen years. But in the process, he labored so relentlessly that he ignored his body’s warning signs and suffered a repetitive stress injury. That didn’t stop him from intensely preparing for and entering the New York City Marathon just a few months later. When that chapter was over, Okazaki again focused on his musical pursuits and proceeded to record several more albums, both as a leader and side musician.

Thisness is Okazaki’s fifth album in a three-year period and reflects his collaborative approach. It features his Trickster band, which includes Mitchell on keyboards, Anthony Tidd on electric bass, and Sean Rickman on drums. Okazaki has worked with each of these musicians for years, both in his own group and in saxophonist Steve Coleman’s, and they’ve developed a creative relationship that made it possible to record complex music quickly. The entire album was recorded over a two-day span with the quartet recording live on day one and overdubs the following day.

The Trickster band (left to right): bassist Anthony Tidd, keyboardist Matt Mitchell, drummer Sean Rickman, and Miles Okazaki.

And the music on Thisness is incredibly complex. Though Okazaki has studied Indian music seriously, his compositions are also somewhat reminiscent of contemporary Western classical music. You’ll see no shortage of odd note groupings, polyrhythms, and mixed meters carving out space for intricate atonal melodies throughout. Plenty of advanced jazz musicians that proudly boast about their ability to play John Coltrane’s “Countdown” in all 12 keys would cower in fear if they were asked to perform some of Okazaki’s works.

Despite the puzzling, esoteric nature of his compositions, Okazaki’s roots draw from the jazz tradition. After initially starting on classical guitar at age 6, he developed an interest in jazz at 12 and was doing solo guitar gigs at a local Italian restaurant by age 13. His first guitar teachers were Michael Townsend and Chuck Easton (a bebop-influenced Berklee grad), and he took music theory group classes in a cabin in the woods with a teacher named Alex Fowler.

Miles Okazaki’s Gear

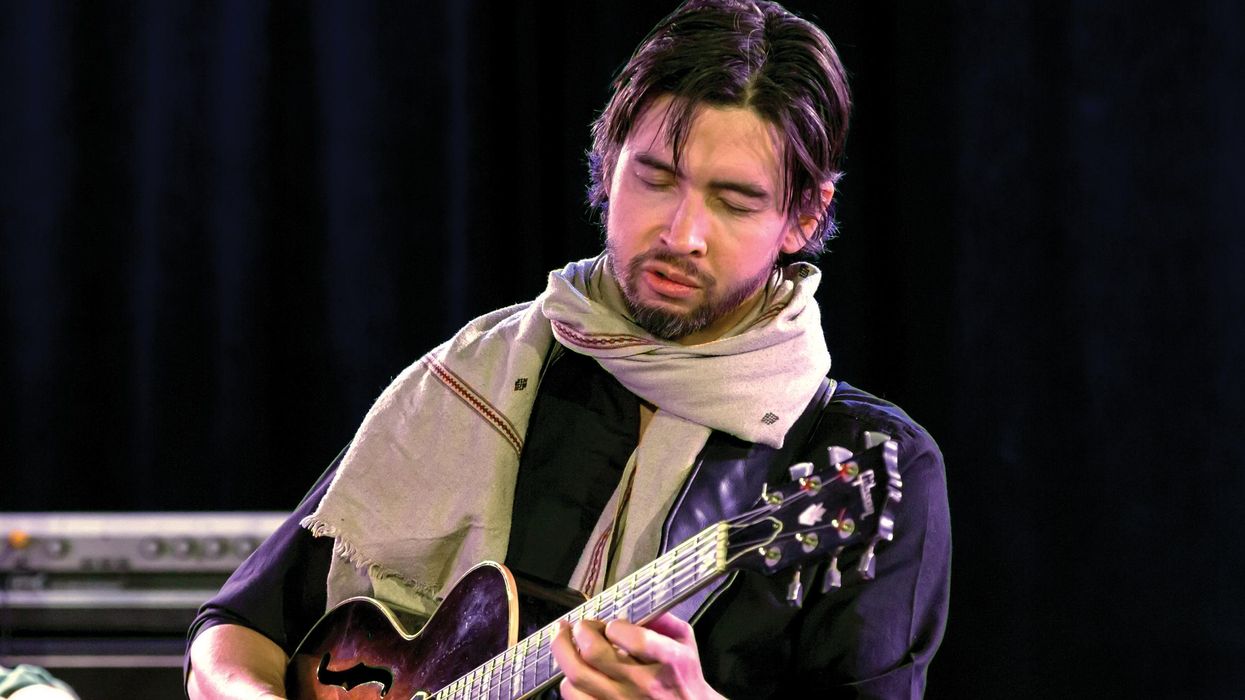

Miles Okazaki can be seen with a host of instruments, but his 1978 Gibson ES-175, which has a Charlie Christian pickup, is his most common 6-string companion.

Photo by John Rogers

Guitars

• 1937 Gibson L-50

• 1940 Gibson ES-150 Charlie Christian (bought with matching EH-150 amp)

• 1963 Gibson C-O Classical

• 1978 Gibson ES-175 with Charlie Christian pickup

• 2018 Slaman “Pauletta” with Charlie Christian pickup modified with adjustable pole pieces drilled into the blade. A hum-canceling coil was recently added by Ilitch Electronics.

• 2002 Yamaha SA2200

• 2016 Kiesel HH2

• 2008 Caius quarter-tone guitar

Amps

• Quilter Aviator Cub

• Quilter Tone Block 200

• Raezer’s Edge Twin 8 cabinet

Effects

• Boss OC-2 Octave

• Boomerang III Phrase Sampler with Side Car controller

• One Control Mosquito Blender Expressio

• Gamechanger Audio Plus Pedal

• Dunlop CBM95 Cry Baby Mini Wah

• Boss RV-5 Digital Reverb

• Analog Man Peppermint Fuzz

• MXR GT-OD

• Electro-Harmonix Micro POG

• Dunlop DVP4 Volume

• Sonic Research ST-300 tuner

Strings and Picks

• Thomastik-Infeld Flatwound .013s (Gibson ES-150 Charlie Christian and Slaman “Pauletta”)

• Thomastik-Infeld Flatwound .014s (Gibson ES-175 with Charlie Christian pickup and Caius)

• Thomastik-Infeld Flatwound .012s (Yamaha SA2200)

• Thomastik-Infeld Flatwound .011s (Kiesel HH2)

• D’Addario Roundwound .014s (Gibson L-50)

• D’Addario Pro-Arte high tension nylon (Gibson C-O)

• Fender .88 mm for .012 strings, 1.0 mm for .014 strings

• Homemade picks using Pick Punch (Preferred material is American Express Delta Sky Miles Credit Card)

• Ilitch Electronics Driftwood pick

• Knobby picks bought from an Instagram metal shredder

During his teens, Okazaki went through a jazz-snob phase, and although he hails from Port Townsend, Washington, he never got into the nearby Seattle scene. “The ’90s, Nirvana and Soundgarden.… No, I kind of missed all that,” he admits. “I was there, but I was into Wes Montgomery and Thelonious Monk. I was stuck in the ’60s and ’50s at that point.” He still cites those musicians, in addition to Grant Green, George Benson, and Charlie Christian (whom he hailed as “the greatest guitarist that ever lived” in a blog post) as influences.

After attending Harvard University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in English Literature, Okazaki came to New York to pursue his master’s degree in guitar at Manhattan School of Music. There, he found a mentor in Rodney Jones, a jazz/R&B player with tremendous chops. “I studied with, and continue to study with, Rodney,” explains Okazaki. “He was my teacher from 1997. I worked pretty closely with him for about 10 years, rebuilding my technique. My technique wasn’t good. You know I didn’t really have a teacher before him that really talked about guitar so much. I had teachers, but it was more just sort of like other people from other instruments. His technique is based on a hybrid George Benson type of deal. It has to do with the picking, but also there are many, many things that have to do with micro movements of the right hand. So, I spent a long time studying that. I still don’t really play like that, but I play kind of like a hybrid version of his hybrid version. Now mine is mixed with some other stuff.”

TIDBIT: On his new album, Okazaki creatively repurposed an influence in his approach to “And Wait for You”: “I played a piece of a Charlie Christian solo that I’m kind of riffing on. That’s a phrase from ‘Stompin’ at the Savoy’ but obviously the context here is a little different.”

Jones referred Okazaki to legendary saxophonist Stanley Turrentine, and Okazaki did a few gigs with the soul-jazz master shortly before his passing in 2000. It was around this period that Okazaki made his mark on the NYC jazz scene. He worked with vocalist Jane Monheit and was initially cast as a straight-ahead guitarist. “For a long time, I was just a standards player. I was pigeonholed in that area,” he recalls. “I did this weird stuff on the side—well, I didn’t consider it to be weird—but it was hard for people in their mind to imagine that you do different things.”

The guitarist found he was able to fully explore other sides of his playing when he landed a gig with Steve Coleman, whose M-Base Collective created a new language of incredibly challenging, forward-thinking music. From 2008 until 2017, Okazaki’s artistry thrived as he played alongside Coleman.

”I don’t know how many people you know that can play in James Brown’s band. It’s harder than playing in my band, that’s for sure.“

Very few players can comfortably hang with both the down-to-earth, bluesy jazz sounds of George Benson and the futuristic, ultra-heady maze of Coleman’s music like Okazaki can. The guitarist sees the two approaches as sharing common heritage. “Benson’s language is blues and R&B, and Steve Coleman’s is, too. There’s different theories and stuff behind it, but it’s not technically different to me,” he explains.

“If it was language, I’m interested in the grammar, not so much what language I’m speaking about,” he explains. “Or if it was cooking, I might be interested in the principles of ‘how do you cook a piece of meat,’ as opposed to, ‘I’m doing French cooking.’ George Benson has a style for sure, and a lot of people, when they learn about George Benson, will also sort of imitate his style. I’ve never been that interested in imitating anybody’s style. I kind of want to have my own style.”

Trickster performs during their recent residency at SEEDS:: Brooklyn.

Photo by Alain Metrailler

Okazaki’s style is radically different from both the sounds of his main guitar influences and other offerings in today’s jazz landscape. His abstruse music has been called academic, but that’s a label the guitarist isn’t particularly fond of. “I would push back a little on ‘academic’ because, first of all, I don’t like academic music,” he says. “I don’t like any type of art that has to be explained. When I go to an art museum, I don’t want to have to read the little blurb. I don’t want anybody to have to know anything about music to appreciate it. There are things involved in how it’s made that are interesting to me, but I don’t care if they’re interesting to anybody else, or I don’t want that to be a feature of it that’s really that important, unless people want to look for that.”

For Okazaki, his music might be also called academic, or complex, or cerebral, but that doesn’t explain his purpose, or set him apart. “James Brown is complex, or Robert Johnson is complex,” he says. “All these things are complex, meaning that they’re not easily explained. I don’t know how many people you know that can play in James Brown’s band. It’s harder than playing in my band, that’s for sure.”

“The test is: Does it sound good, or does it not sound good? That’s the only question for me.”

Complexity comes in many forms. Just because a piece of music happens to be based on one chord “that doesn’t mean that it’s simple,” Okazaki observes. He believes the opposite is true as well. “There are things that take a lot of work, and there’s a lot of machinations involved, and a lot of manipulation of materials and thought, and construction, and it still sounds like shit,” he laughs. “And there are things that are just one chord and amazing.”

As much as Okazaki is known as a musical thinker who can throw down some heavy information in his compositions and playing, what matters most is how it sounds. “It might look good on paper, but if it doesn’t sound like anything, then it’s not good,” he says. “The test is: Does it sound good, or does it not sound good? That’s the only question for me.”Trickster's Dream - "The Lighthouse"

The Trickster band was scheduled to go on a six-week tour starting in May 2020 but got derailed by the Covid lockdowns. Instead, they created a video concert featuring music from Okazaki’s 2019 release, The Sky Below. This version of “The Lighthouse” is from those sessions and captures the band conjuring the energy and spirit of playing to a captive audience.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.