There are big rock bands, and then there are bands that completely change the sonic landscape. Korn is definitely one of the latter. The moment this Bakersfield 5-piece’s first single, “Blind” hit the airwaves in the mid ’90s, grunge died, hip-hop was adopted by the heavy rock crowd, and Metallica was no longer the metal band to beat. From that point on, metal had to be down-tuned, groovy, and exceptionally twisted.

Their impact on the guitar was even more dramatic. The band’s earth-moving use of the Ibanez 7-string guitar brought more notoriety to the design than the instrument’s guitar-hero designer, Steve Vai, ever did. And when they paired these extended range instruments with Mesa/Boogie Triple Rectifiers, a gut-rumbling sound was pounded into the metal-guitar vernacular that has remained a standard to this day.

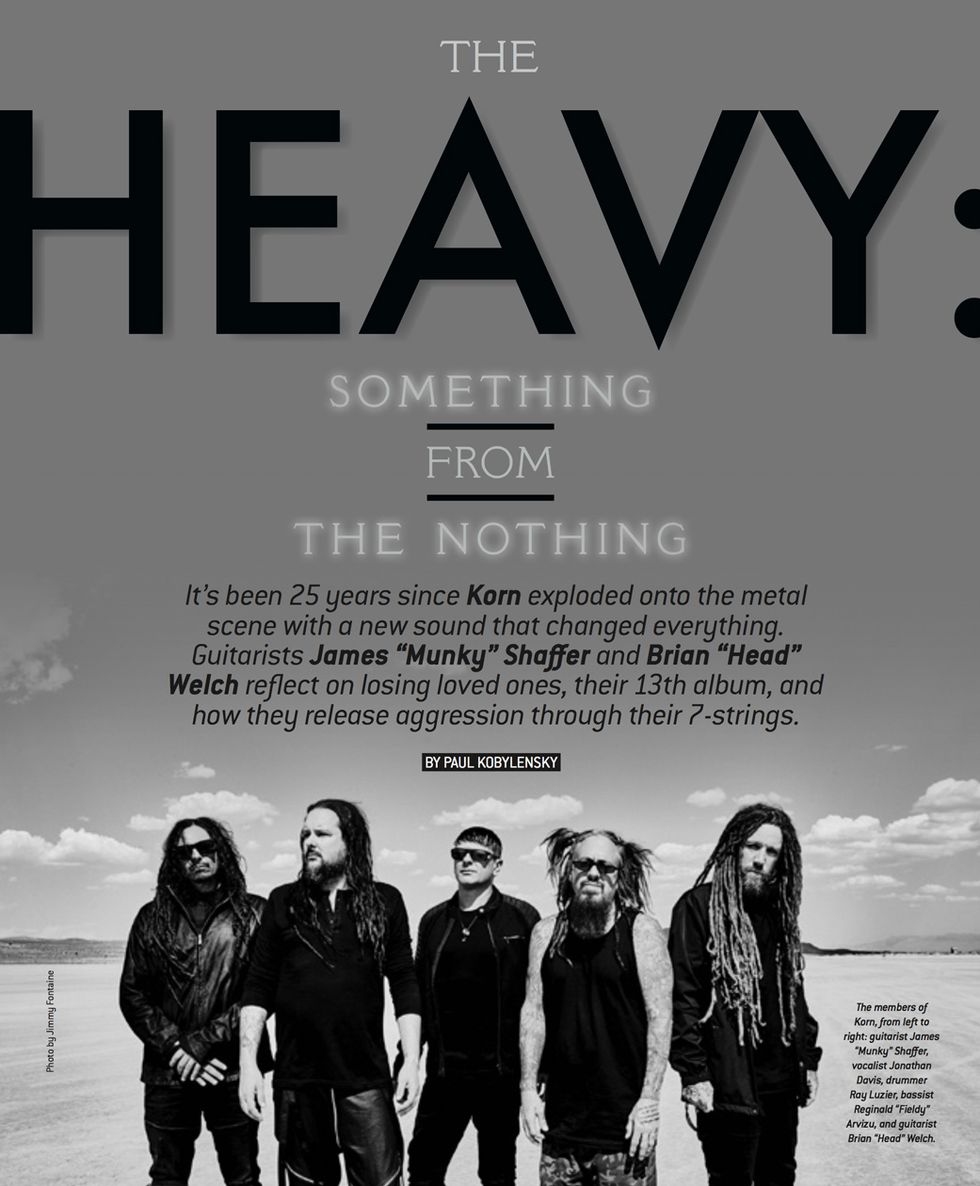

Korn enjoyed a meteoric rise to fame, but the sound they fearlessly pioneered, now called nu-metal, was soon aped by thousands of me-too bands who watered down its impact and created a tidal wave of backlash. Down-tuned riffing, emotionally frightening vocals, and hip-hop influence were now to be avoided like the plague. However, Korn—guitarist Brian “Head” Welch, guitarist James “Munky” Shaffer, vocalist Jonathan Davis, bassist Reginald “Fieldy” Arvizu, and Ray Luzier on drums (Luzier replaced David Silveria in 2007)—always seemed to be the one band to maintain their loyal fanbase and continue delivering the goods.

That’s thanks in large part to their willingness to experiment with their winning formula. After Brian “Head” Welch temporarily left the band in 2005, they began taking some chances with their music that kept fans scratching their heads. See You on the Other Side (2005) boasted a hefty list of co-writing credits with pop mega-hit writers like Matrix, responsible for such chart-topping artists as Shakira, Avril Lavigne, and Britney Spears. Then came 2011’s The Path of Totality, which blended in a massive dose of EDM heavyweights, including Skrillex, Noisia, and Excision.

Since then, Head rejoined his brothers in Korn, officially in 2013. And, with his help, they’ve begun steering the massive ship back to their beloved, gut-pummeling, emotion-wrenching sound.

“The first record with me back [Paradigm Shift] was more electronic-based with a little bit of heavy mixed in,” he remembers. “But [Serenity of] Suffering was heavy. And now this one’s even more. It’s been a process of making sure everyone can enjoy making music and enjoy Korn.”

Longing for heavy riffs was only part of what has brought the band roaring back. The last few years have also been filled with personal and professional tragedy, including the death of Davis’ ex-wife and some of their most celebrated peers and heroes in the music industry. Needless to say, they had plenty to write about when they hit the studio, and it all culminated in their most recent offering, The Nothing.

The album opens with Korn’s trademark bagpipes as Davis’ familiar roar mixes with his equally identifiable pain-filled cries. As soon as the album’s first full song, “Cold,” kicks into gear, it’s clear that Korn has returned. But it’s the album’s fifth track, “Idiosyncrasy,” that may be the best example of their current sonic incarnation. From the clicking slap bass and pulverizing metal tones to the “Got the Life”-like disco-drum beat in the chorus, everything that made the band great is on full display. And each of these elements has been given a shot of adrenaline, making them heavier, groovier, and more powerful than they’ve ever been.

Much of that power can be attributed to producer Nick Raskulinecz, who has built an impressive resume helping such iconic bands as Rush, Alice in Chains, and Mastodon maximize the impact of their unique attributes. And he does it while continually pushing the bands for more than even they knew they were capable of.

“He’s listening from a perspective, a vantage point, that really lends to being objective,” James “Munky” Shaffer points out. “He’ll say, ‘Let’s not do that. I feel like I’ve heard that from you guys, and it sounds typical for Korn.’ But we also don’t want people to forget who we really are.”

It’s safe to say The Nothing has achieved on both fronts: new, pulverizing production and plenty of Korn’s iconic character. Fans can always count on Korn to eventually return to their roots. But it’s been a long journey back this time around—one defined by loss, renewed friendships, and sonic discovery. But they’re finally here.

Munky and Head took time with Premier Guitar to reflect on this journey. In their familiar, laid-back, California way, they detail how everything that went into The Nothing still came down to coping with life through 7-strings and Mesa/Boogies.

The Nothing has some of Korn’s heaviest moments in years. What inspired a return to such an aggressive sound?

Head: What helped a lot on this record was Jonathan falling in love with heavy music again. We don’t want to make him do something he didn’t want to do. But he just fell in love with it again.

Then having Nick Raskulinecz onboard, he used to flip burgers and listen to “Here to Stay” at the burger joint. He’s like, “Dude, I know what I want to hear as a fan.” We were all on the same page. That’s how it ended up, this type of record.

Korn’s 13th studio album was produced by Nick Raskulinecz, who also produced Korn’s 2016 album, The Serenity of Suffering.

Munky: I also think, the tragic loss of some of our heroes recently, like Chester [Bennington], Chris Cornell, and Vinnie Paul. There’s frustration there. That frustration turns to anger, and the only way we know how to release it is through our music. These artists influenced us and influenced us to make it really aggressive. And it tears out your soul when you hear about these tragedies that could’ve been prevented. I think a lot of it came from there.

That also goes for Jonathan’s tragedy. All that pain and anger and not knowing what to do reflects in the music.

The album seems to combine all of your trademark elements, but they’re amplified to new levels. Is it important to keep those “Korn-isms” front and center?

Head: We don’t sit there and go, “We want to sound like this record.” We’re just going day by day. It’s like, “What do you want to hear today, John?” He’ll say, “Think Vulgar Display of Power today.” That’s what sparked that opening riff for “Idiosyncrasy.”

Munky: There’s definitely a balancing act that has to take place. Sometimes we get really comfortable doing what we do. Fieldy is really comfortable playing his bass that way. But sometimes, we have to pull some out and focus on the meat and potatoes of the song. It’s like, “Does it sound enough like Korn? We’ve done that so many times, maybe we don’t need to do that here.” That’s where Nick Raskulinecz really helps.

What is it like working with Nick, and how did he push you to try new things?

Munky: It doesn’t feel like work. It’s like, “Let’s go in and have some fun. Come on, man.” It’s not like clocking in and putting in the hours. We’d play until we’re burned each day. Jonathan has a different story because the lyrics are a whole ’nother animal. But for us, writing the music is, “Does it feel good? Are you happy with it?”

Head: Honestly, he’s another member of the band. And he’s a fan from back in the day. But we know that he’s leading the project with us. He is a producer, and we’re following his lead. But it goes both ways. If he comes in with an idea and we’re not feeling it, we just change it.

Head’s signature Ibanez KOMRAD was his go-to axe before switching to ESP in 2017. Head’s guitar approach is “melodic,” while he describes his guitar cohort Munky as a “mad scientist.” Photo by Annie Atlasman

How were you guys able to stretch out as guitarists on this album?

Munky: I just tried a lot of new chord voicings. I tried to spread those chord voicings out across different amps and get to a wider tone. I’d pull back the main rhythms and let the voicings in the chord use different amps and different sounds, placing it in the far-left speaker or the far-right speaker. I think that Jerry [Cantrell] actually did that on the [Alice in] Chains album. That’s what Nick said anyway.

Did you track each note of the chord separately?

Munky: Some of the stuff, yes.

Head: I’d say, messing with the Kemper for some atmospheric sounds. I’m the guy that loves simple notes that move you because of the sound and the atmosphere, like on “Falling Away from Me.” I’m just trying to think of what would move us live and what would move the crowd. “What are we going to do to make the crowd just go nuts?” That’s what we’re thinking on this record.

Your playing styles have always perfectly complemented each other. How would you define each other’s style?

Munky: I think through the years, our roles became more defined. He definitely has this great sense of melody. Whenever I start to play this weird chord progression, he has this gift of coming up with amazing melodies that lift and bring out notes that I didn’t even hear.

I tend to gravitate towards more of a textural sound. I’m always trying to make my guitar not sound like a guitar. I think a lot of people do that, because you push the boundaries of your guitar, whether it’s with pedals or whatever. I’m always reaching for those unconventional sounds, and he’s always reaching in towards the deeper melody. I think that’s why it works so well.

Head: He’s the mad-scientist type of guy. He sounds more intricate. His notes sometimes will be that trippy, Mr. Bungle, robotic feeling. I’m more melodic. Usually, we know who is playing what because that’s how we track it.

But live, Munky can play everything. All the stuff played on the record, he’s always taking the challenge. He wants the challenging parts, and I’m like, “Go right ahead!” [Laughs.]

It’s fascinating that neither one of you mentioned the heavy riffs, which is the core of everything.

Head: Heavy riffs could go to either one of us. Whoever has the riff has the riff. It’s probably about 50-50 nowadays. Nick brought in a couple riff ideas, too. I can’t remember which ones. Fieldy came in this record with a couple things.

When you guys hit the scene, you changed the rules of heavy metal. One of the most obvious was the use of 7-string guitars. And Ibanez has always been along for the ride. Is that still the case?

Munky: When you hear the Korn records through the years, 90 percent of every rhythm track is done on those Ibanez 7-strings. We’ve done a lot of signature stuff in the past. And now we’re about to release a new one. It’s going to be called the K720, marking our 20th anniversary of the first K7.

Wow, congratulations.

Munky: Thank you. It’s really cool. I’m so excited to let people see this guitar because I can’t believe it’s been that long. It’s a real honor to work with the company and for so long. They’ve been so loyal, and they’ve always tried to accommodate the crazy ideas that we have.

Guitars

ESP LTD SH-7 EverTune Brian “Head” Welch signature 7-string

ESP SH-7 EverTune custom signature 7-string

Amps

Mesa/Boogie Triple Rectifier

Bogner Shiva (studio only)

Diezel Herbert (studio only)

Kemper Profiler (studio only)

Mesa/Boogie Rectifier 4x12 with Celestion Vintage 30s

Effects

Chase Bliss Audio Tonal Recall

Boss CE-5 Chorus Ensemble

Boss RV-5 Reverb

DigiTech XP-100 Whammy-Wah

Various Uni-Vibe-style pedals

Strings and Picks

D’Addario XL 7-string sets (.010–.060)

Dunlop Tortex .73 mm

Guitars

Ibanez K7 signature 7-strings

Ibanez APEX200 signature 7-strings

Ibanez K720 20th Anniversary signature 7-string

Amps

Mesa/Boogie Triple Rectifier

Bogner Uberschall (studio only)

Diezel VH4 (studio only)

Kemper Profiler (live clean tones only)

Mesa/Boogie Rectifier 4x12 with Celestion Vintage 30s

Effects

Dunlop 105Q Cry Baby Bass Wah

DigiTech XP-100 Whammy-Wah

Various Uni-Vibe-style pedals

WMD Geiger Counter

Malekko Downer

MXR Phase 90

Ibanez BC-9 Bi-Mode Chorus

Boss RV-5 Reverb

Boss Metal Zone (live AM radio sounds)

Electro-Harmonix Micro-Synth

Boss DD-3 Delay

Electro-Harmonix Memory Boy

Various Devi Ever pedals (studio only)

Various EarthQuaker Devices pedals (studio only)

Strings and Picks

D’Addario XL 7-string sets (.010–.060)

Dunlop Tortex .73 mm

Head, you were a long time Ibanez player but released your signature Sir Headley 7-string with ESP in 2017. Why the move to ESP?

Head: There were changes at Ibanez, and people that we knew for years were gone. I also started to get involved with searching out this EverTune idea. With our low tuning, I was in love with that because there have always been tuning issues live. I have to switch guitars a lot. I wanted something more dependable. I heard ESP were the forerunners with putting that system on the guitar. Munky actually was the one who told me to check them out.

I have some off-the-rack ones that I bring on tour, and I have some custom ones. I have LTDs and, I think, two ESP customs. But they’re all very similar, and they play the same. I can’t tell the difference.

Did you track the album with your ESPs?

Head: Oh, yes. Heck, yes. We pulled in some old vintage guitars a little bit, and, if needed, Munky will throw me his guitar. But I’d say 95 percent was my ESP.

You guys are also synonymous with the Mesa/Boogie Triple Rectifier. Is that still the formula for your trademark tone?

Munky: It’s usually a combination. Each track, we use a few different combinations of amps. For main rhythms, I used a Bogner [Uberschall] with a Triple Rectifier and a Diezel [VH4] going into three separate cabinets. They’d each be miked with two mics and then a room mic. You’re getting six microphones back to three channels. Each rhythm track is a texture of that, which is pretty intense. Then, of course, if you’re doubling it, it sounds like a frickin’ freight train.

Head’s got his own setup. His other amps were a Diezel Herbert and Bogner Shiva.

I remember watching your Rig Rundown from 2013. I was struck with how few pedals you both use to get all of your different tones. Is that still the case?

Munky: Yes. It’s how we play. It’s this thing we’ve developed that’s a combination of the effects and a pick scrape or something. What sounds like it might be three or four pedals is only one pedal with a specific technique. We try to keep it simple but sound complicated.

What kind of pedals did you guys use in the studio? What are some of your go-to’s?

Munky: Our go-to’s are the XP-100 [Whammy] from DigiTech and an old Ibanez chorus pedal. Another pedal that I love is called the [WMD] Geiger Counter. It has endless amounts of fuzz. It’s the one sound you hear just before the bridge of “You’ll Never Find Me.”

Malekko has made some really cool shit lately. They have a few pedals that I used on the new record. One of them is called the Downer. It’s a pretty crazy-sounding octave-fuzz type thing. I also have a few of their modular things because I’m getting into that old modular scene.

Head: Munky is the mad scientist. The dude sits there with that sound generator. He sits there and tweaks out on it for four hours. I’m like, “What are you doing?” He goes, “I don’t know. It just makes my anxiety go away.” It gives me anxiety. [Laughs.] He has all these weird pedals that make these weird sounds, and he’ll experiment.

I’ve had, like, six pedals for years. I changed a couple just recently. But for the most part, I’ve kept to about five pedals, and I adjust the levels and modulation for different songs. I want something familiar so I can concentrate on the song, the melodies, and the heavy riffs. I’m just more of a simple dude that way.

Korn changed the sound of metal with your very first single. That sound was eventually tagged nu-metal and got a lot of backlash. Why was Korn able to rise above that and remain such an influential band?

Head: We have a darker edge than a lot of those bands did back in the day. Also, we were never a rap-metal band. We had some guests that rap. But Jonathan never rapped. He was always darker. He was into the Cure growing up, and he had a Nine Inch Nails influence. I feel like he stood on his own.

Munky: There’s always those purists that say, “That’s not what metal is about.” But I felt like, “Well, hey, man, we’re doing what we love to do. It sounds good, and it feels good to create something different.”

Through the years, we kept our heads down and tried not to pay attention to what everybody else was saying and doing. It just continued to evolve and work. We just really care that our fans are loving it.

James “Munky” Shaffer has played Ibanez 7-strings since Korn’s beginning in the 1990s. Here he’s playing one of his APEX200 signature models. Photo by Annie Atlasman

Why do you think your sound has resonated with so many people for so long?

Munky: I think as we all got older and started to write heavier music, then Jonathan started to dig deep and find his voice. It’s very real, and it resonates with people. It helps them through hard, difficult times and makes them feel like they’re not alone.

Head: Korn is therapy to Jonathan, and I think it’s therapy for a lot of our fans.

Munky: We didn’t know we were doing this, and that’s the beauty of it. I think that’s why it’s lasted so long. It’s only now that we realized that we’ve helped so many people through music.

Korn really represents one of the last evolutions in heavy rock in popular culture. Do you think that heavy, guitar-driven rock is going to come back?

Munky: I think history always repeats itself. I don’t think you can remove the instrument out of popular music. You can’t escape that feeling that playing gives somebody. It’s just a powerful instrument for some reason. That’s why the instrument’s been around forever. It’s one of those universal things that anybody can pick up and play no matter where they are.

Massive riffs, danceable grooves, slap bass, twisted melodies, and aerial dance. It’s all there in this official live video of The Nothing’s latest single, “Cold.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)