Bassist and Union Leader Dave Pomeroy Makes Players’ Rights the Bottom Line in Nashville

Dave Pomeroy and a few of his best friends.

Organized labor has shaped the music we love, and Nashville Musicians Association president Dave Pomeroy believes musicians still need a fair deal.

“There’s always something to do in Nashville,” grins Dave Pomeroy. For Pomeroy, this is especially true. He’s the president of the Nashville Musicians Association (NMA), the city’s branch, or “local,” of the American Federation of Musicians (also known as AFM Local 257). The AFM is the largest musicians’ union in North America, representing around 70,000 music workers through more than 240 locals across the continent.

It’s no surprise that Music City’s local comes with a fair bit of history. Along with New York, Memphis, Chicago, and Los Angeles, Nashville is one of the most important cities in the trajectory of not only American music, but the business that shaped that music. As the recorded music and radio industries exploded in the 1940s and ’50s, musicians found themselves in uncharted waters. Suddenly, there were new and enormous revenue streams—royalties and record sales—and musicians weren’t getting their share. Record labels were getting fat off the surplus.

So, the AFM organized the biggest music workers’ direct action in history. For nearly two years between 1942 and 1944, the AFM’s roughly 136,000 members engaged in a recording ban: They refused to produce any new recordings for the record labels until they were guaranteed a fair cut of the new profits. Some top talents like Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman stood by the strikers. Others, like Frank Sinatra, scabbed, and used non-union musicians on their recordings when AFM musicians refused. (I guess that’s why it’s “My Way,” not “Our Way.”)

Dave Pomeroy & the All-Bass Orchestra: "Buckle Up"

The strikes were successful, though later challenges and divisions within the movement diminished the initial victories. Still, it showed that the collective power of organized labor could go toe-to-toe with corporations, and get what musicians are owed for the magic they create. Musicians nowadays, who are up “streaming creek” without a paddle, need as much help as they can get. “The music business doesn’t have to be a win-lose,” says Pomeroy. “It can be a win-win when everybody treats each other the right way.”

“The music business doesn’t have to be a win-lose. It can be a win-win when everybody treats each other the right way.”

Pomeroy was raised a military kid, born in Italy and later moving to England with his family in 1961. He got a head start on the Beatles, and stayed up late to watch them make their debut on The Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964. The Rolling Stones caught his ear just before his family uprooted to northern Virginia, where Pomeroy took piano lessons and played clarinet in the school band. He wanted to play the cello, but those spots were filled, so he took up the string bass at age 10. A couple years later, he discovered the bass guitar, which suited him just fine; he could dance around and sing with a bass hung across his shoulders. His parents helped him acquire a Gibson EB-2 (his hero Jack Bruce played Gibson basses, so he had to, too).

Pomeroy joined a folk trio in his second year at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, a turning point when he realized music was his destiny. He left school and moved to Belgium, where his parents were stationed at NATO. He quickly moved to London, where he played in five different bands in a year. Following a short stint in Denmark (his Hamburg, he quips) his European sabbatical was over, and it was time to get back stateside. One of his bandmates from Charlottesville had a publishing deal in Nashville, so Pomeroy decided to give it a go. That was 46 years ago.

Pomeroy hit the road with Don Williams in 1980, and quickly learned the value of mutual respect and fair working conditions.

Rockabilly icon Sleepy LaBeef gave Pomeroy his first gig. LaBeef was a human jukebox, and would switch up sets every night. The law of the band was simple: Follow, or die. It was a crash course in ear and style training for Pomeroy. He bounced around until he landed his big break: backing up Texas country slinger Don Williams. Pomeroy played in Williams’ band for 14 years, from 1980 to 1994, and that time would shape the rest of his life. It was an incredible musical education, and it bridged him to new worlds in the music industry.

But more than those things, it was the consideration that Williams showed his musicians that changed Pomeroy’s life. “He treated us with great respect,” he explains, “and I didn’t realize for some time that that was not the norm, and that it was a lot worse for a lot of my colleagues and friends.” At 24, Pomeroy co-wrote a song with Williams, who helped get him a publishing deal. Williams also landed his road band a record deal on his label ,MCA and co-produced their self-titled “Scratch Band” record.

“He treated us with great respect, and I didn’t realize for some time that that was not the norm, and that it was a lot worse for a lot of my colleagues and friends.”

Working with Williams cemented the value of documenting his work with a union contract. In 1980, Williams and his band played a show at Giant Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey. A month later, Pomeroy’s friend called to tell him to turn his TV on. The gig had been recorded for Casey Kasem’s America’s Top 10 program, and was airing. Pomeroy was over the moon, but things got even better—a short time later, he got a $1,000 check for the airing. When it aired again, he got another $1,000.

Dave Pomeroy's Gear

Over his 46 years in Nashville, Pomeroy has worked with the biggest stars of country and folk music. Emmylou Harris, performing with Pomeroy here in December 2023, brought him along to her sessions with the Chieftains in 1992.

Photo by Mickey Dobó

Basses

- Fleishman Custom 5-string electric upright

- 1967 Gibson EB-2

- G&L Fretted and fretless L-2000

- 1963 Fender Precision

- Alleva-Coppolo 5-string

- 1964 Framus Star Bass

- Reverend Rumblefish 4- and 5-strings

- Brad Houser 5-string

- 1980s Gibson Thunderbird fretted and fretless

- Lakland Jerry Scheff 5-string

- 1940s Kay

- Hamer 12-string

- Pedulla 8-string fretless

- Gold Tone Micro-Bass, Banjo, and Dobro

- Kala U-Basses – hollowbody and solidbody

- Jerry Jones 6-string baritone “tic-tac” bass

- Boulder Creek 4-string fretless and 5-string fretted acoustic basses

- Music Man 5-string

- Sadowsky 4-string

- Big Johnson – large acoustic fretted bass

Amps

- Genzler Magellan 800 Head with Genzler cabs

Effects

- Boss GT-10B

- Boss RC-50

- Boss RC-600

- SWR Mo’ Bass preamp

- Ampeg SVT preamp

- Line 6 Bass POD Pro

- Avalon U5 Class A Active Instrument DI and Preamp

- Trace Elliot V-Type preamp

- Morley wah pedal

- Morley volume pedal

Strings

- GHS Pressurewound, Brite Flats, Boomers, Flatwounds, and Round Cores

- Thomastick acoustic bass strings

“I thought, ‘Holy moly, this is how this stuff works?’” remembers Pomeroy. “There were so many times that we’d find out about these things with other artists, and nobody bothered to say anything; nobody turned it into paperwork. [They would say,] ‘Oh, I didn’t know we were supposed to get paid.’ I didn’t know we were supposed to get paid, but somebody took care of it. That was just the way Don was.”

Over the years, Pomeroy would perform and record with many celebrated artists, musicians, and songwriters in country, folk ,and bluegrass music, such as Earl Scruggs, Guy Clark, George Jones, Emmylou Harris, Chet Atkins, and Alison Krauss. He honed his voice on the instrument when he got an upright fretless electric bass, which he played on Keith Whitley’s 1988 record, Don’t Close Your Eyes. Pomeroy’s dramatic downward slide on “I’m No Stranger to the Rain” had his phone ringing off the hook. Harris invited him to play on her album, “Bluebird,” and he also joined her recording with The Chieftains in 1992, when she asked him to bring along “the bass from space,” her nickname for his electric upright. Pomeroy’s outside-of-the-box streak continued on his performances and arrangements of his song “The Day the Bass Players Took Over the World,” and his All-Bass Orchestra.

“They basically said, ‘Hey, these are our friends, and we’re not going to screw them over … We’re going to do this right.’”

Eventually, his path curved toward the studio world, where he started to take more notice of the local union’s role in making music. In the early 2000s, Pomeroy gravitated towards a subgroup of the AFM called the Recording Musicians Association, where he revived a sense of participation and engagement in negotiations. In 2008, he ran against the NMA’s incumbent president, Harold Bradley, who had held the post for 18 years. Pomeroy won the election, and has held the seat ever since.

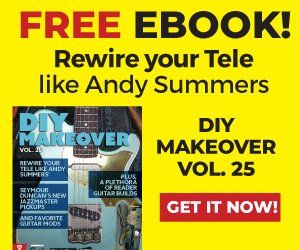

Pomeroy has advocated for better working conditions for artists for decades, including supporting the Fair Play Fair Pay Act in 2017, which addressed issues with terrestrial radio.

Photo courtesy of the Music First Coalition

The AFM’s single-song overdub scale agreement, a/k/a home studio contract, was created by NMA in 2012, and it wasn’t easy. There were drawn-out debates over where the pay floor should be. “Are we talking about ‘Mary Had a Little Lamb’ or are we talking about Mahler’s Symphony No. 6?,” says Pomeroy. The minimum, they decided, was $100, which can be negotiated upwards, depending on the difficulty of the job. But instead of simply being handing the player a crisp Benjamin, the employer would sign a piece of paper allowing the player to pay into their own pension, a first for AFM musicians.

The AFM “Tracks on Tour” contract was also a NMA creation. When Dolly Parton and Jason Aldean wanted to use recorded tracks onstage as part of their shows, they went to the NMA to work out how to do it right.

“I’m nice, but I’m also very persistent. I’m a Taurus. I’m not going to let things go. We’re going to work this out.”

Parton wanted a saxophone part in one of her songs without touring with a saxophonist, and Aldean wanted to use the acoustic guitar and piano from his hit ballad with Kelly Carson, “Don’t You Wanna Stay.” So, the NMA studied a Broadway touring show’s pay rates to come up with a scale for that situation, and the performers whose recorded work was being played earned up to $12,000 extra in a year, thanks to the formula. Some artists, says Pomeroy, can scheme their way around the scales by getting their road band to rerecord the parts for less money. “But a lot of artists are willing to pay to have the good stuff,” he says.

Pomeroy explains that at the start of its golden era, Nashville’s recording business was built on respect between employers and creators. Big labels like Decca and RCA Victor were run by Owen Bradley and Chet Atkins, respectively, and even though the labels wanted to turn a profit on “hillbilly music,” Bradley and Atkins were wise enough to know that they ought to give musicians a fair deal. “They basically said, ‘Hey, these are our friends, and we’re not going to screw them over. We got to play with them Saturday night at the country club, so we’re going to do this right, and do it on a union contract,’’ Pomeroy shares.

Pomeroy’s music and union work aren’t separate—they’re both part of a single vision, where artists can create and perform with dignity.

Photo by Jim McGuire

Sometimes, the dividends for doing this “right” are immediate and obvious. But other times, like Pomeroy experienced, they might take a little while to manifest. In 2014, Mazda used Patsy Cline’s “Back In Baby’s Arms” in a commercial for their new RX-7 car that ran for 2 years. A 90-year-old violinist who played in the song’s string section came into the NMA offices one day to pick up a New Use check for nearly $2,000. He told Pomeroy he’d been paid $57 to record his parts back in 1962. “That makes all the work worthwhile,” says Pomeroy.

A decent chunk of his work, says Pomeroy, falls into dealing with well-meaning people who might not have known they were shortchanging a musician, but need some reminding, all the same, to pony up. Other times, he and the AFM have to push a little harder to get musicians what they’re owed. “I chase people down,” says Pomeroy. “I’m nice, but I’m also very persistent. I’m a Taurus. I’m not going to let things go; we’re going to work this out.” Pomeroy says they’ve successfully sued for nearly a million dollars from employers who “didn’t want to do the right thing, and got to do the right thing the hard way.” Some of those people end up on Music City’s “Most Wanted”: the Nashville Musicians Association’s “Do Not Work For” list. It exists to warn both performers and the public about employers who are known to either break union contracts, or solicit union musicians to work outside a union contract.

All of this might seem separate or secondary to the actual creation and performance of music. But that belief, whether held subconsciously or expressed explicitly, is what has allowed musicians to remain overworked and underpaid for the past century, or more. If we really believe that music brings value to our lives, why shouldn’t the labor that enables its creation be supported fairly? And besides, musicians are workers like any other. If you saw a boss raking in stacks of cash while their employees struggled to make rent, you’d be pissed off, right? Well, that’s the situation a lot of music workers find themselves in these days. Pomeroy and the AFM have their work cut out for them.

But, it’s easier for Pomeroy when he sees a common ground between his music work and his union work. Sometimes, they collide, like on his song, “What Unions Did for You.” Each feeds and emboldens the other. “I have to have the creative stuff to balance out the administrative stuff,” says Pomeroy. “But in a lot of ways, the admin stuff that I do is a lot like being a bass player. You’re rushing, you’re dragging, it’s right here in the middle; let’s see if we can find that place where everybody’s gonna feel good.”

YouTube It

Dave Pomeroy bops through a solo performance of the riotous, bassman’s-rights tune “The Day the Bass Players Took Over the World” at the Country Music Hall of Fame.

- Jazz Bassist Scott Colley Talks About His Early Days ›

- Nashville’s Buddy Miller: From the Roots to the Cosmos ›

- Nashville Flood-Damaged Guitars Up For Auction ›

A rig meant to inspire! That’s Jerry Garcia with his Doug Irwin-built Tiger guitar, in front of his Twin Reverb + McIntosh + JBL amp rig.

Three decades after the final Grateful Dead performance, Jerry Garcia’s sound continues to cast a long shadow. Guitarists Jeff Mattson of Dark Star Orchestra, Tom Hamilton of JRAD, and Bella Rayne explain how they interpret Garcia’s legacy musically and with their gear.

“I met Jerry Garcia once, in 1992, at the bar at the Ritz Carlton in New York,” Dark Star Orchestra guitarist Jeff Mattson tells me over the phone. Nearly sixty-seven years old, Mattson is one of the longest-running members of the Grateful Dead tribute band scene, which encompasses hundreds of groups worldwide. The guitarist is old enough to have lived through most of the arc ofthe actual Grateful Dead’s career. As a young teen, he first absorbed their music by borrowing their seminal records, American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead, brand new then, from his local library to spin on his turntable. Around that same moment, he started studying jazz guitar. Between 1973 and 1995, Mattson saw the Dead play live hundreds of times, formed the landmark jam bandZen Tricksters, and later stepped into theJerry Garcia lead guitarist role with the Dark Star Orchestra (DSO), one of the leading Dead tribute acts.

“At the bar, I didn’t even tellGarcia I was a guitar player,” Mattson explains. “I had just heard him play the new song ‘Days Between’ and I told him how excited I was by it, and he told me he was excited too. It wasn’t that long of a conversation, but I got to shake his hand and tell him how much his music meant to me. It’s a very sweet memory.”

The Grateful Dead’s final studio album was 1989’sBuilt to Last, and that title was prophetic. From 1965 to 1995, the band combined psychedelic rock with folk, blues, country, jazz, and even touches of prog rock and funk, placing a premium on improvisation and pushing into their own unique musical spaces. Along the way, they earned a reputation that placed them among the greatest American bands in rock ’n’ roll history—to many, the ultimate. Although no one member was more important than another, the heart and soul of the ensemble was Garcia. After his death in 1995, the surviving members retired the name the Grateful Dead.

“I think Jerry Garcia was the most creative guitarist of the 20th century because he had the widest ears and the sharpest instincts,” opines historian, author, and official Grateful Dead biographer Dennis McNally, over the phone. “What we see after his death are the Deadheads coming to terms with his passing but indicating that it’s the music that was most important to them. And who plays the music now becomes simply a matter of taste.”

Dark Star Orchestra guitarist Jeff Mattson, seen here with Garcia’s Alligator Stratocaster (yes, the real one).

Photo by Susana Millman

This year marks 30 years since Garcia’s passing and 60 years since the band formed in the San Francisco Bay Area. Today, the guitarist’s musical vocabulary and unique, personal tone manifests in new generations of players. Perhaps the most visible of these musicians is John Mayer, anointed as Garcia’s “replacement” in Dead and Co. But dozens of others, like Mattson, Tom Hamilton Jr., and a young new artist named Bella Rayne, strive to keep the Dead alive.

The first few Grateful Dead tribute bands began emerging in local dive bars by the late ’70s. More than mere cover bands, these groups devoted themselves entirely to playing the Dead. A few of these early groups eventually toured the country, playing in college towns, ski resorts, and small theatres across the United States. Mattson started one on Long Island, New York. He tells me, “The first band I was in that played exclusively Grateful Dead was Wild Oats. It was 1977, and we played local bars. Then, in 1979, I joined a band called the Volunteers. We also played almost exclusively the Grateful Dead, and that was a much more professional outfit—we had a good PA and lights and a truck, the whole nine yards.” The Volunteers eventually morphed into the Zen Tricksters.

Garcia’s death turbocharged the Dead tribute band landscape. Fanbases grew, and some bands reached the point where big-time agents booked them into blue-chip venues like Red Rocks and the Beacon Theatre. Summer festivals devoted to these bands evolved.

“The first band I was in that played exclusively Grateful Dead was Wild Oats. It was 1977, and we played local bars.” —Jeff Mattson

Dark Star Orchestra launched in 1997, and they do something particular, taking an individual show from somewhere out of Grateful Dead history and recreating that evening’s setlist. It’s musically and sonically challenging. They try to use era-specific gear, so on any given night, they may be playing through recreations of the Grateful Dead’s backline from 1971 or 1981, for example. It all depends on the show they choose to present. Mattson joined DSO as its lead guitar player in 2009.

Something else significant happened after Jerry died: The remaining living members of the Grateful Dead and other musicians from Garcia’s inner circle embraced the tribute scene, inviting musicians steeped in their music to step up and sit in with them. For Mattson, it’s meant playing over the years with all the core members of the band, Phil Lesh, Bob Weir, Bill Kreutzmann, and Mickey Hart, plus former members Donna Jean Godchaux, who sang in the band from 1971 to 1979, and Tom Constanten, who played keyboards with the Dead from 1968 to 1970.

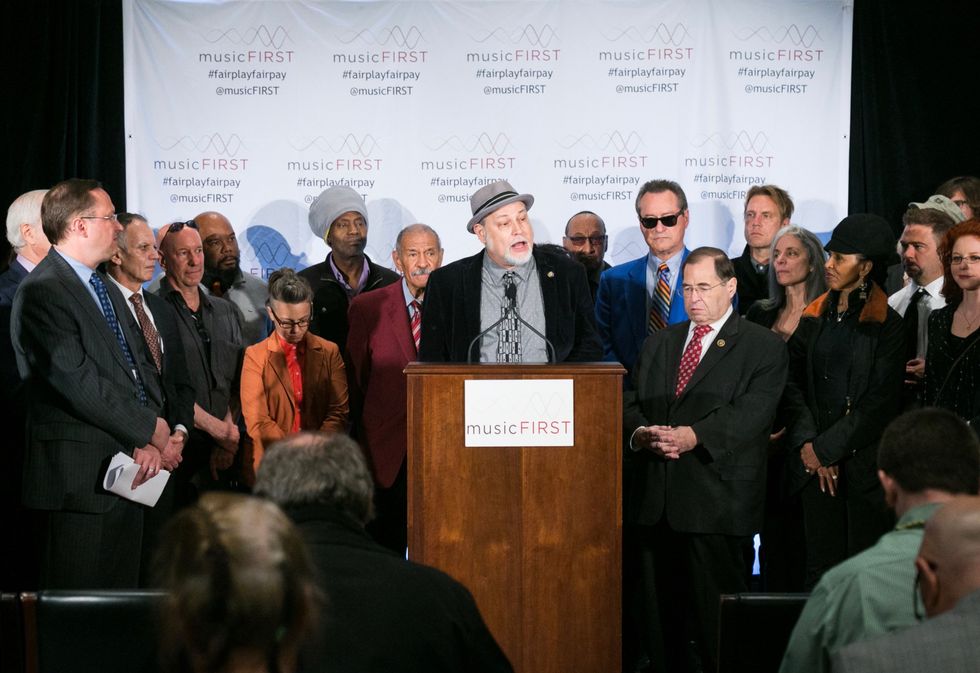

Tom Hamilton’s Lotto custom built had a Doug Irwin-inspired upper horn.

In the newest post-Garcia tribute bands, many guitar players aren’t old enough to have seen Garcia perform live—or if they did, it was towards the end of his life and career. One of those guys sitting today at the top of the Garcia pyramid, along with Mattson, is Tom Hamilton Jr. Growing up in a musical family in Philadelphia, Hamilton saw Garcia play live only three times. Early on, he was influenced by Stevie Ray Vaughan, but Hamilton’s older brother, who was also a guitar player, loved the Dead and Garcia. “My brother wanted to play like Jerry,” he recalls, “so he roped me in because he needed me to play ‘Bob Weir’ and be his rhythm guitar sidekick.” Eventually, Hamilton leaned more into the Jerry role himself. “Then I spent my entire twenties trying to develop my own voice as a songwriter and as a guitar player. And I did,” Hamilton says. “And during that time, I met Joe Russo. He was not so much into the Dead then, but he knew I was.”

A drummer from Brooklyn, by about 2006, Russo found himself collaborating on projects with members of Phish and Ween. That put him on the radar of Lesh and Weir, who invited Russo to be a part of their post-Dead project Furthur in 2009. (And on guitar, they chose DSO founding member John Kadlecik, opening that role up for Mattson.)

“When Joe played in Furthur, he got under the hood of the Grateful Dead’s music and started to understand how special it was,” Hamilton points out. “After Furthur wound down, we decided to form JRAD. We weren’t trying to do something academic, not some note-for-note recreation. We were coming at it through the pure joy of the songs, and the fact that the five of us in JRAD were improvisers ourselves.”

“We were coming at it through the pure joy of the songs, and the fact that the five of us in JRAD were improvisers ourselves.” —Tom Hamilton Jr.

Today, Joe Russo’s Almost Dead (JRAD) is considered to be one of the premier Grateful Dead tribute bands. They formed in 2013, with Hamilton and Scott Metzger as the band’s guitar frontline, with Hamilton handling Garcia’s vocal roles. Eventually, Hamilton, too, found himself jamming onstage with the ever-evolving Phil Lesh and Friends. That, of course, further enmeshed him in the scene, and in 2015, he started a band with Dead drummer Bill Kreutzmann calledBilly and the Kids.

Now, there’s a new kid on the block, literally. Bella Rayne recently turned 18 and grew up in Mendocino, California. Her parents were into the Dead, but even they were too young to have really followed the original band around the country. At her age, they were big into Phish. By the pandemic, Bella started embracing the guitar out of boredom, woodshedding while social distancing in quarantine. She explains, “Like any other teen, I was bored out of my mind looking for anything to do.” Rummaging through her garage, she came across her mom’s old Strat. “At the time, I was really into ’90s Seattle grunge. I put new strings on the Strat, and then I tried to teach myself Pearl Jam songs, and I learned how to play them by watching YouTube videos. Then, I started posting videos of my journey online as I became more serious about it. I hit a point where I knew it would be my thing. The next thing I knew, one of the Bay Area Dead bands [China Dolls] reached out to me and asked me to sit in. I thought, ‘no way.’“My parents are huge Deadheads,” she continues. “That’s theirthing. I grew up with the Dead being pushed on me my whole life. But I ended up going, and it’s just been this awesome spiral ever since.” Bella calls her current Dead-related project Bella Rayne and Friends, and she, too, has been recognized not only by the new generation of Garcia players in the Dead tribute bands, but also by Melvin Seals, the Hammond organist who played for years in theJerry Garcia Band. “I was hired to just sit-in for a couple of numbers withMelvin and his JGB band,” she recalls, “and we were having so much fun he said to me, ‘Why don’t you just sit in for the whole second set.’ It was an amazing night.”

Bella Rayne with her Alligator-inspired Strat, with a JGB Cats Under the Starssticker on the body.

Photo by Sean Reiter

Jerry Garcia played many different guitars. But for those guitarists wanting to emulate Garcia’s tone, the focus is on four instruments in particular. One is a1955 Fender Stratocaster known as “Alligator,” which Garcia had heavily modified and began playing in 1971. The other three guitars were hand built in Northern California by luthier Doug Irwin: Wolf, Tiger, and Rosebud. Garcia introduced them in 1973, 1979, and 1989, respectively. Sometimes, in a jam-band version of being knighted by the Excalibur sword, a chosen member of this next generation of Dead players is handed one of Garcia’s personal guitars to play onstage for a few songs or even an entire set.

Although they started their journeys at different times and in separate ways, Mattson, Hamilton, and Rayne all have “knighthood” in common. Rayne remembers, “In March of 2024, I was sitting in one night with anall-girl Dead tribute band called the China Dolls, and no one had told me that Jerry’s actual 1955 Strat, Alligator, was there that evening. My friend [roots musician] Alex Jordan handed me the guitar unannounced. It’s something I’ll never forget.”What’s it like to strap on one of Jerry Garcia’s iconic instruments? Tom Hamilton recalls, “It wasRed Rocks in 2017, and I played with Bob Weir, Melvin Seals, and JGB at a tribute show for Jerry’s 75th birthday. I got to play both Wolf and Tiger that night. I was in my head with it for about one song, but then you sort of have a job to do. But I do recall that we were playing the song ‘Deal.’ I have a [DigiTech] Whammy pedal that has a two-octave pitch raise on it, real high gain that gives me a lot of sustain, and it’s a trick I use that really peaks a jam. That night, while I am doing it, I had the thought of, ‘Wow, I can’t believe I am doing this trick of mine on Garcia’s guitar.’ Jerry would have thought what I was doing was the greatest thing in the world or the absolute worst, but either way, I’m cool with it!”

“I was sitting in one night with an all-girl Dead tribute band called the China Dolls, and no one had told me that Jerry’s actual 1955 Strat, Alligator, was there that evening. My friend [roots musician] Alex Jordan handed me the guitar unannounced. It’s something I’ll never forget.” —Bella Rayne

Jeff Mattson has played Alligator, Wolf, Garcia’s Travis Bean 500, and his Martin D-28. He sums it up this way: “I used to have posters up in my childhood bedroom of Garcia playing his Alligator guitar. I would stare at those images all the time. And sowhen I got a chance to play it and plug it in, suddenly there were those distinctive tones. Those guitars of his all have a certain mojo. It’s so great to play those guitars that you have to stop in the moment and remind yourself to take a mental picture, so it doesn’t just fly by. It’s just a tremendous pleasure and an honor. I never imagined I would get to play four of Jerry Garcia’s guitars.”

With young people like Bella Rayne dedicating herself at the tender age of 18 to keeping the Dead’s music going, it feels like what the band called their “long strange trip” will keep rolling down the tracks and far over the horizon. “People will be listening to the Grateful Dead in one hundred years the same way they will be listening to John Coltrane, too,” predicts McNally. “Improvisational music is like jumping off a cliff. Sometimes you fly, and sometimes you land on the rocks. When you take that risk, there’s an opportunity for magic to happen. And that will always appeal to a certain segment of people who don’t want predictability in the music they listen to. The Grateful Dead is for people who want complete craziness in their music—sometimes leading to disaster and oftentimes leading to something wonderful. It’s music for people who want to be surprised.”

Detail of Ted’s 1997 National resonator tricone.

What instruments should you bring to an acoustic performance? These days, with sonic innovations and the shifting definition of just what an acoustic performance is, anything goes.

I believe it was Shakespeare who wrote: “To unplug, or not to unplug, that is the question. Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of acoustic purists, or to take thy electric guitar in hand to navigate the sea of solo performing.”

Four-hundred-and-twenty-four years later, many of us still sometimes face the dilemma of good William when it comes to playing solo gigs. In a stripped-down setting, where it’s just us and our songs, do we opt to play an acoustic instrument, which might seem more fitting—or at least more common, in the folksinger/troubadour tradition—or do we bring a comfy electric for accompaniment?

For me, and likely many of you, it depends. If I’m playing one or two songs in a coffeehouse-like atmosphere, I’m likely to bring an acoustic. But if I’m doing a quick solo pop up, say, as a buffer between bands in a rock room, I’m bringing my electric. And when I’m doing a solo concert, where I’ll be stretching out for at least an hour, it’s a hybrid rig. I’ll bring my battered old Guild D25C, a National tricone resonator, and my faithful Zuzu electric with coil-splitting, and likely my gig pedalboard, or at least a digital delay. And each guitar is in a different tuning. Be prepared, as the Boy Scouts motto states. (For the record, I never made it past Webelos.)

My point is, the definition of the “acoustic” or “coffeehouse” performance has changed. Sure, there are still a few Alan Lomax types out there who will complain that an electric guitar or band is too loud, but they are the last vestiges of the folk police. And, well, acoustic guitar amplification is so good these days that I’ve been at shows where each strum of a flattop box has threatened to take my head off. My band Coyote Motel even plays Nashville’s hallowed songwriter room the Bluebird Café as a fully electric five-piece. What’s key, besides a smart, flexible sound engineer, is controlling volume, and with a Cali76 compressor or an MXR Duke of Tone, I can get the drive and sustain I need at a low level.

“My point is, the definition of the ‘acoustic’ or ‘coffeehouse’ performance has changed.”

So, today I think the instruments that are right for “acoustic” gigs are whatever makes you happiest. Left to my own devices, I like my Guild for songs that have a strong basis in folk or country writing, my National for blues and slide, and my electric for whenever I feel like adding a little sonic sauce or showing off a bit, since I have a fluid fingerpicking hand that can add some flash to accompaniment and solos. It’s really a matter of what instrument or instruments make you most comfortable because we should all be happy and comfortable onstage—whether that stage is in an arena or theater, a club or coffeehouse, or a church basement.

At this point, with instruments like Fender’s Acoustasonic line, or piezo-equipped models from Godin, PRS, and others, and the innovative L.R. Baggs AEG-1, it’s worth considering just what exactly makes a guitar acoustic. Is it sound? In which case there’s a wide-open playing field. Or is it a variation on the classic open-bodied instrument that uses a soundhole to move air? And if we arrive at the same end, do the means matter? There is excellent craftsmanship available today throughout the entire guitar spectrum, including foreign-built models, so maybe we can finally put the concerns of Shakespeare to rest and accept that “acoustic” has simply come to mean “low volume.”

Another reason I’m thinking out loud about this is because this is our annual acoustic issue. And so we’re featuring Jason Isbell, on the heels of his solo acoustic album, a piece on how acoustic guitars do their work authored by none other than Lloyd Baggs, and Andy Fairweather Low, whose new solo album—and illustrious career—includes exceptional acoustic performances. If you’re not familiar with his work, and you are, even if you don’t know it, he was the gent sitting next to Clapton for the historic 1992 Unplugged concert—and lots more. There are also reviews of new instruments from Taylor, Martin, and Godin that fit the classic acoustic profile, so dig in, and to heck with the slings and arrows!Ernie Ball, the world’s leading manufacturer of premium guitar strings and accessories, proudly announces the launch of the all-new Earthwood Bell Bronze acoustic guitar strings. Developed in close collaboration with Grammy Award-winning guitarist JohnMayer, Bell Bronze strings are engineered to meet Mayer’s exacting performance standards, offering players a bold new voice for their acoustic guitars.Crafted using a proprietary alloy inspired by the metals traditionally found in bells and cymbals, Earthwood Bell Bronze strings deliver a uniquely rich, full-bodied tone with enhanced clarity, harmonic content, and projection—making them the most sonically complex acoustic strings in the Ernie Ball lineup to date.

“Earthwood Bell Bronze strings are a giant leap forward in tone, playability, and durability. They’re great in any musical setting but really shine when played solo. There’s an orchestral quality to them.” -John Mayer

Product Features:

- Developed in collaboration with John Mayer

- Big, bold sound

- Inspired by alloys used for bells and cymbals

- Increased resonance with improved projection and sustain

- Patent-pending alloy unique to Ernie Ball stringsHow is Bell Bronze different?

- Richer and fuller sound than 80/20 and Phosphor Bronze without sounding dark

- Similar top end to 80/20 Bronze with richer low end than Phosphor Bronze

The Irish post-punk band’s three guitarists go for Fairlane, Fenders, and a fake on their spring American tour.

We caught up with guitarists Carlos O’Connell and Conor Curley from red-hot Dublin indie rock outfit Fontaines D.C. for a Rig Rundown in 2023, but we felt bad missing bassist Conor “Deego” Deegan III, so we’ve been waiting for the lads to make their way back.

This time, riding the success of their fourth LP, 2024’s Romance, we caught up with all three of them at Nashville’s Marathon Music Works ahead of their April 30 gig to see what they brought across the pond.

Brought to you by D’Addario

All’s Fairlane

Curley’s go-to is this Fairlane Zephyr, loaded with Monty’s P-90s and a Mastery bridge. It mostly stays in standard tuning and, like his other axes, has Ernie Ball Burly Slinky strings.

Blue Boy

Fender sent Curley this Jazzmaster a couple of years ago, and since then, he’s turned to it for heavier, more driven sounds. It’s tuned to E flat, but Curley also tunes it to a unique shoegaze-y tuning for their tune “Sundowner.”

You can also catch Curley playing a Fender Johnny Marr Jaguar.

Twin Win

Fender Twin Reverbs are where Conor Curley feels most comfortable, so they’re his go-to backline. The amps are EQ’d fairly flat to operate as pedal platforms.

Conor Curley’s Pedalboard

Curley’s pedalboard for this tour includes a TC Electronic PolyTune3 Noir, Strymon Timeline, Boss RV-6, Boss PN-2, Boss BF-3, Keeley Loomer, Death by Audio Echo Dream, Fairfield Circuitry Hors d'Ouevre?, Strymon Sunset, Strymon Deco, DigiTech Hardwire RV-7, Electro-Harmonix Nano POG, and Lehle Little Dual.

Fake Out

Connor Deegan didn’t own a bass when Fontaines D.C. began, and his first purchase was the black Fender Jazz bass (right)—or so he thought. He later discovered it was a total knock-off, with a China-made body, Mexico-made neck, and a serial number that belongs to a Jaguar. But he fell in love with it, and its sound—nasal on the high strings, with cheap high-output pickups—is all over the band’s first record, Dogrel. Deego plays with orange Dunlop .60 mm picks, and uses Rotosound Swing Bass 66 strings.

Deegan picked up the Squier Bass VI (left) for its “surfy vibes,” and upgraded the pickups and bridge.

Also in his arsenal is this 1972 Fender P-bass (middle). (He’s a bit nervous to check the serial number.)

V-4 You Go

Deego plays through an Ampeg V-4B head into a Fender 6x10 cabinet.

Conor Deegan’s Pedalboard

Deegan’s board includes a Boss TU-3, Electro-Harmonix Hum Debugger, Boss TR-2, modded Ibanez Analog Delay, Death by Audio Reverberation Machine, Boss CE-2w, Tech 21 SansAmp Bass Driver DI, Darkglass Electronics Alpha Omega Ultra, and Dunlop Volume (X) Mini pedal. A GigRig QuarterMaster helps him switch sounds.

Mustang Muscle

Carlos O’Connell favors this 1964 Fender Mustang, which has been upgraded with a Seymour Duncan Hot Rails pickup since Romance. It’s set up so that the single-coil pickup is always on, and he’ll add in the Hot Rails signal for particular moments.

Ghost of Gallagher

Mustang Muscle

Mustang MuscleAfter getting to play a number of Rory Gallagher’s guitars thanks to a private invitation from the guitarist’s estate, O’Connell picked up this Fender Custom Shop Rory Gallagher Signature Stratocaster. The jangly, direct tone of this one is all over tunes like “Boys in the Better Land.”

More Fender Friends

O’Connell runs his guitars, including a vintage Martin acoustic which he picked up in Nashville, through a Fender Twin Reverb and Deluxe Reverb.

Carlos O’Connell’s Pedalboard

The gem of O’Connell’s board is this Soundgas 636p, an imitation of the infamous Grampian 636 mic preamp’s breakup. Alongside it are a TC Electronic PolyTune, Ceriatone Centura, Strymon Volante, Eventide H9, Orchid Electronics Audio 1:1 Isolator, Vein-Tap Murder One, MXR Micro Amp, Moog MF Flange, MXR Smart Gate, and Freqscene Koldwave Analog Chorus. A Radial BigShot ABY navigates between the Twin and Deluxe Reverb.