Delay pedals are among the most popular effects around, and the reason is simple: A delay pedal not only gives your sound a professional sheen and adds a three-dimensional quality—even when set for a discreet, atmospheric effect—but it can also produce a wide variety of not-so-subtle sounds and textures, ranging from ear-twisting rhythmic repeats (à la Eddie Van Halen's “Cathedral") to faux twin-guitar harmonies and live looping.

This how-to guide will cover the aforementioned effects, as well as fundamentals like the function of typical delay controls, and where to place your unit in an effects chain. Although there are countless delays on the market—many of which have mind-boggling features—we're going to use a basic delay pedal setup similar to what you'll find on a Boss DD-7 as our reference point. We've also provided some sample settings so you can get the most out of your delay pedal right away.

Delay Pedal Controls

Three controls are common to virtually all delay units: Time, Feedback (sometimes labeled "Repeat" or "Regeneration"), and Level (or "Mix").

Time controls the length of time between any two repetitions of your signal. It is most often measured in milliseconds (ms). Most delay pedals don't have a delay-time readout that would enable you to determine exact delay times in milliseconds, so you typically just adjust the Time knob to get an approximate time based on the unit's available range. For instance, the Boss DD-7 (street $179) has a Mode knob that selects between four time ranges—up to 50 ms, 51–200 ms, 201–800 ms, and 801–3200 ms—and the Time knob then adjusts the setting within the selected range.

Feedback determines the amount of repetitions. At its minimum setting, Feedback outputs a single repetition of the original signal. From that point on, as you turn up Feedback you get more repeats. Some delay units allow infinite repeats when this control is maxed.

Level controls the volume of the repeats. When Level is at its minimum setting, you won't hear any repeats. When it's all the way up, the repeats should be as loud as the original signal.

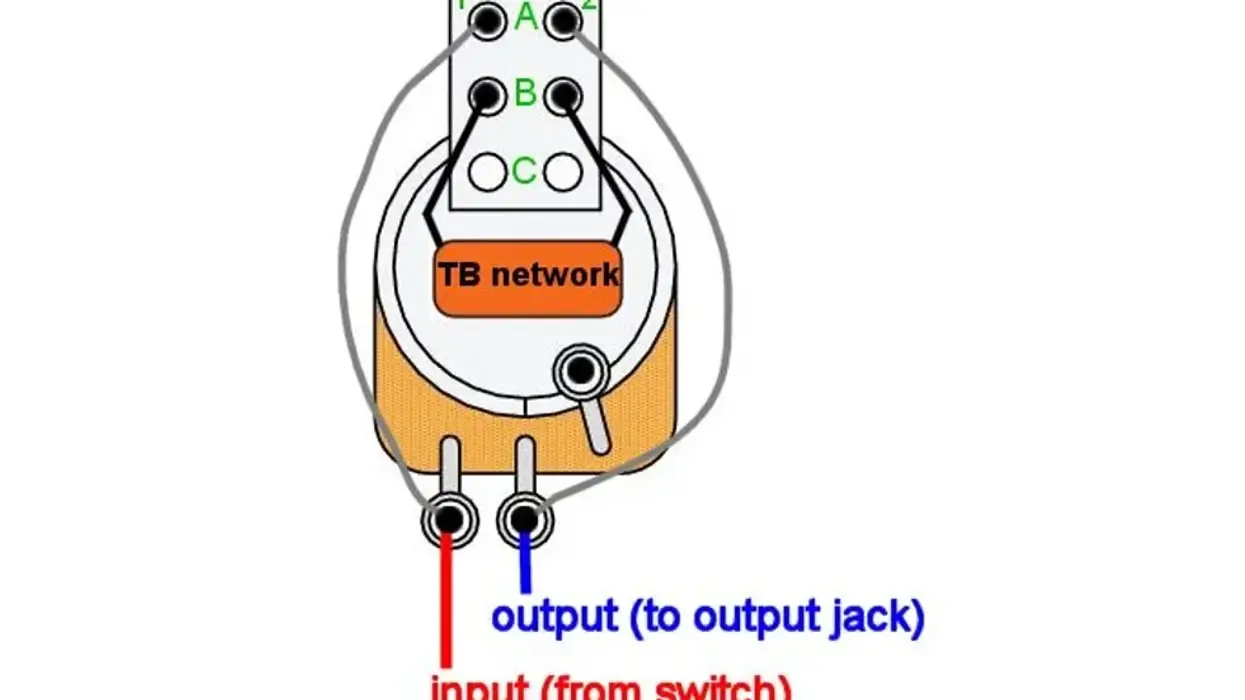

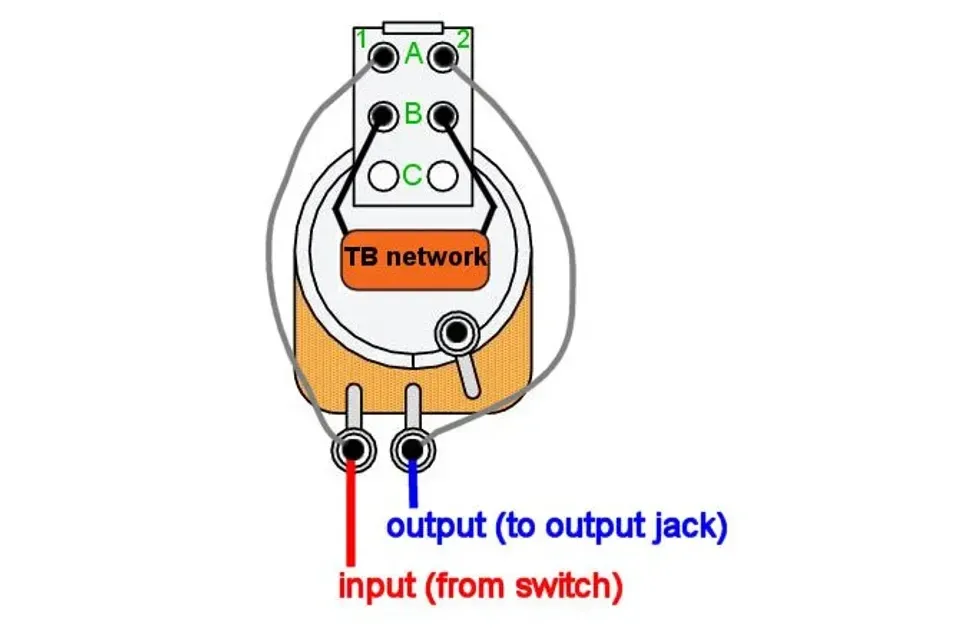

Signal-Chain Placement

If you plan to use your delay in conjunction with other stompboxes, it's important to consider where to place these effects in the chain—especially if you're using an overdrive, distortion, or fuzz pedal. The most common setup is to place dirt before delay. This is important because it means you'll be delaying the distorted signal as opposed to distorting a delayed signal, which will sound mushy and indistinct. Because a distortion pedal has the strongest impact on your fundamental tone, it's typically placed early in the chain, whereas delay is usually placed toward the end of the chain so it can produce repeats of all of the effects added to your guitar sound. Of course, you should experiment for yourself to see what you prefer.

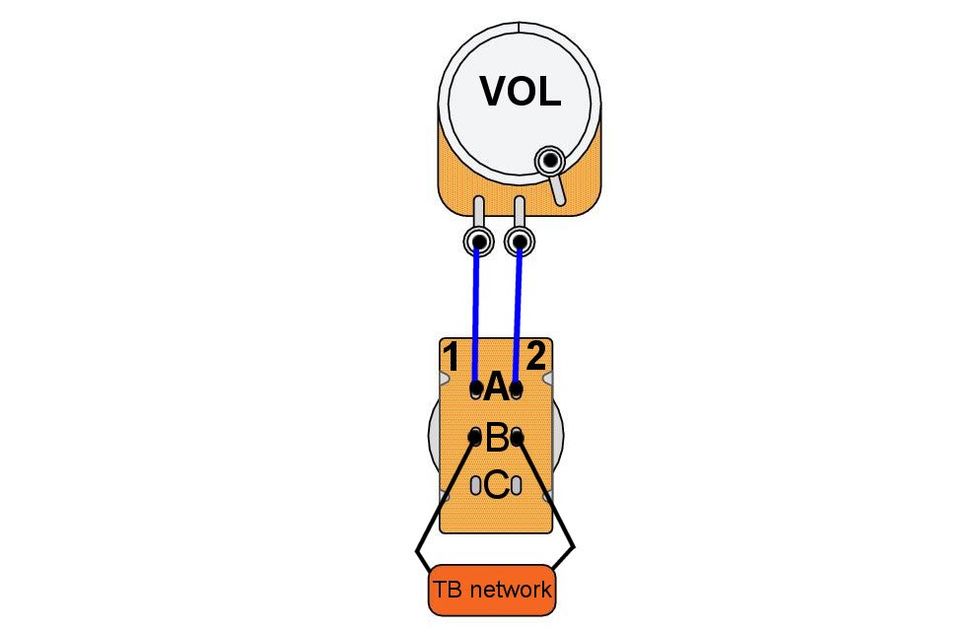

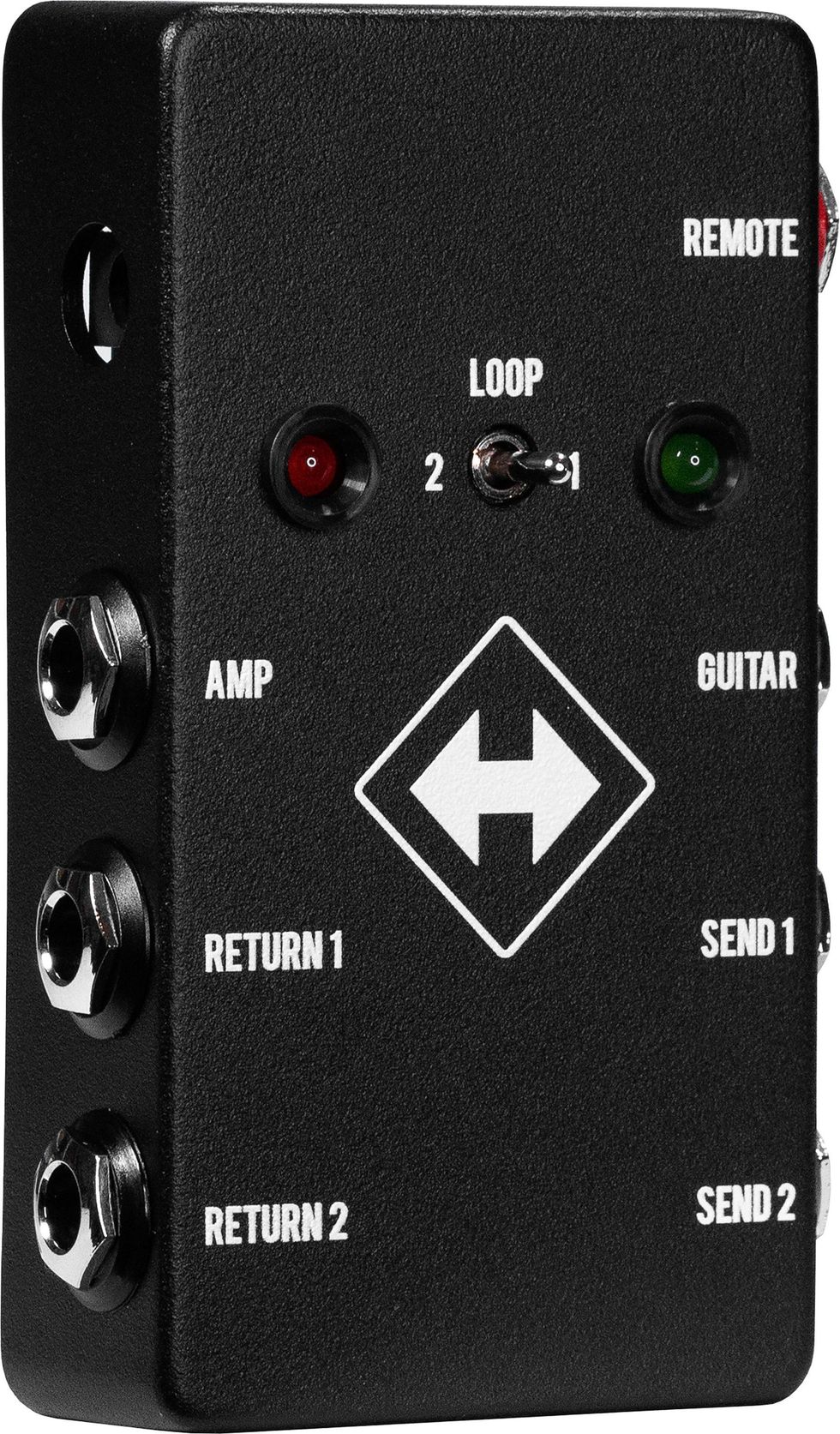

If you're taking the dirt-before-delay with the distortion from your amp, then you'll want to insert your delay into your amp's effects loop (if it has one) so that it comes in the chain after the preamp gain. For recording, it's less of an issue because you can just record the amp without any effects and then add delay during post-production.

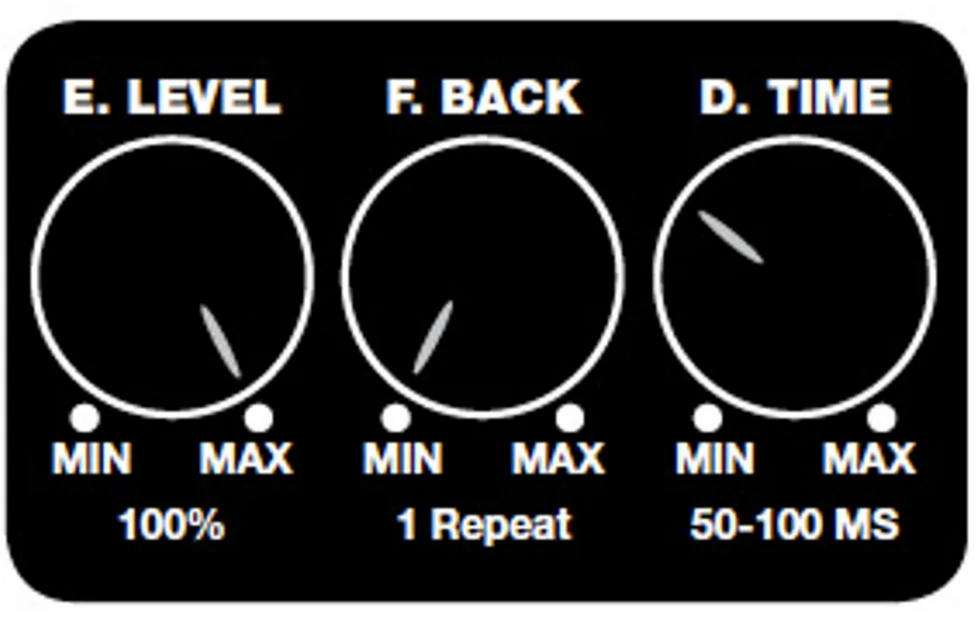

Doubling and Modulation

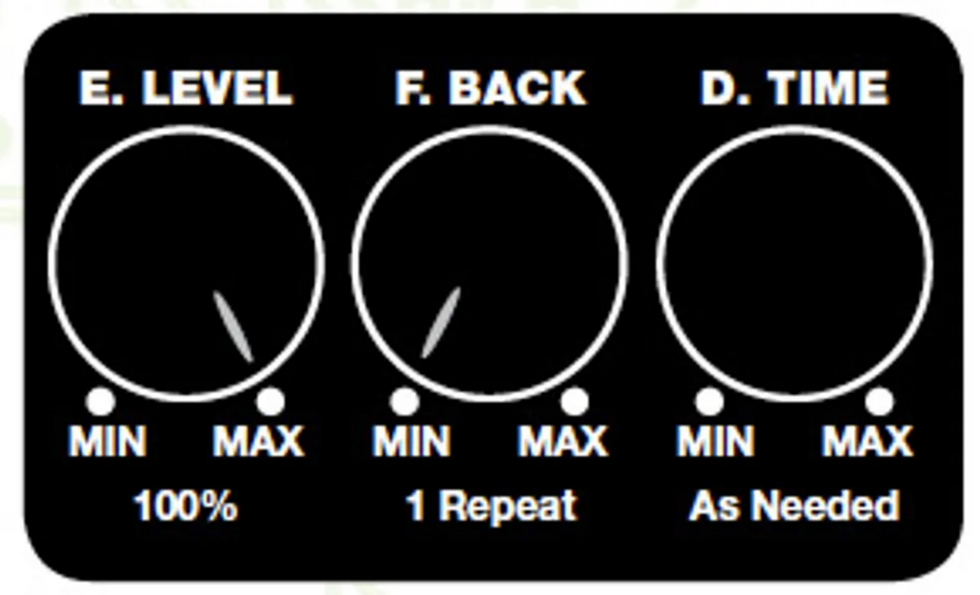

The term "doubling" refers to the process of using a subtle delay to thicken your sound. To get a doubling effect, set Time between 50 and 100 ms, Feedback for minimal repeats (one or two), and Level all the way up. Because the repeat happens so quickly, it creates the illusion of another guitar playing in unison with the original signal rather than sounding like an echo. If you use a lower delay time (20 to 50 ms), you can also get pseudo chorusing and flanging sounds.

Doubling and Modulation Example

Slapback Echo

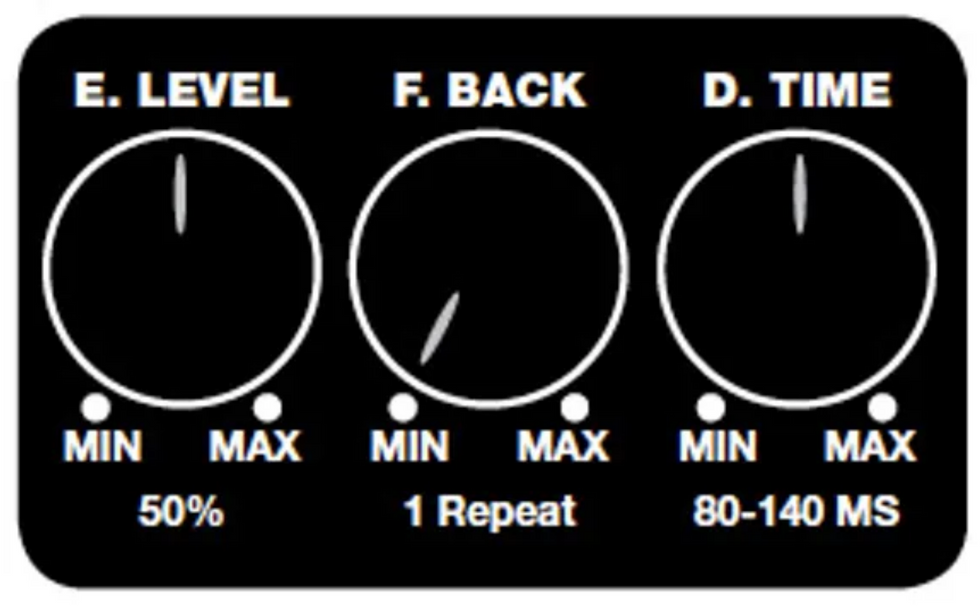

Slapback is a single short repeat similar to a tape slap (the time delay between the record and play heads in an analog tape recorder), and it is most often heard in rockabilly and country. To achieve a slapback effect, keep the Time short (between 80–140 ms), Feedback at 0 (so you only get one repeat), and Level at about 50 percent.

Slapback Example

Faux Reverb

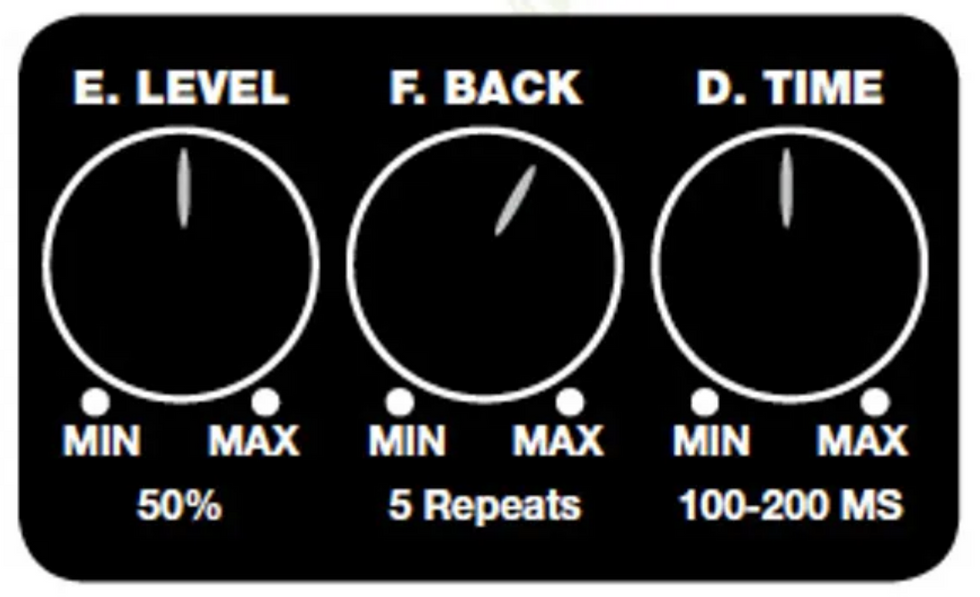

A reverb-type effect can be achieved by modifying some of the settings used for slapback. Set the Time between 100 and 200 ms, Feedback for about 5 repeats, and Level at about 50 percent.

Faux Reverb Example

Tempo Matching

Most delay pedals do not have precise delay time readings on their knob panels. This isn't a crucial issue when you're using shorter delay times or when precise timing of the repeats is not integral to the performance. However, if you're playing to a fixed beat source (say, a band or rhythm track) with a delay time of more than 200 ms and a fairly high Level setting that gives the repeats a distinct note, it will sound best if you dial in a precise delay time that matches the tempo of the band or rhythm track. Otherwise, the repeats will be out of time against the underlying beat. If your music is delay based, delay pedals such as the Providence DLY-4 Chrono Delay (street $449), TC Electronic ND-1 Nova Delay (street $259), and Strymon Timeline (street $449)—all of which feature LED readouts of the delay time—are worth considering.

Newer digital delays such as the Providence DLy-4 Chrono Delay, TC Electronic ND-1 Nova Delay, and Strymon Timeline feature exact millisecond readouts for players who need very precise delays for tempo-matching purposes.

Many delay pedals from the last decade or so offer a happy middle ground with tap-tempo functionality (some designs require using an aftermarket external footswitch to access this). If you're familiar with the term but aren't quite sure exactly how it works, here's the scoop: Though many players don't know the exact tempo they need in terms of beats per minute (bpm), most have an innate sense of the tempo they wish to play at, so tapping it out on a delay pedal's tap-tempo footswitch is an easy way to get the sort of tempo matching we've been talking about. If your delay doesn't have tap-tempo functionality, or if you want a formulaic approach to calculating the delay time, see the "Calculating MSfrom BPM" sidebar.

Dotted-Eighth Rhythmic Repeats

Guitarists like Eddie Van Halen, the Edge, and David Gilmour took delays to new heights by making them an integral part of compositions like Van Halen's "Cathedral," U2's "Where the Streets have No Name," and Pink Floyd's "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 1." They popularized a trick using dotted-eighth-note delay repeats to create the illusion that they were playing more notes—and faster—than they really were.

Dotted-Eighth Rhythmic Repeat Example

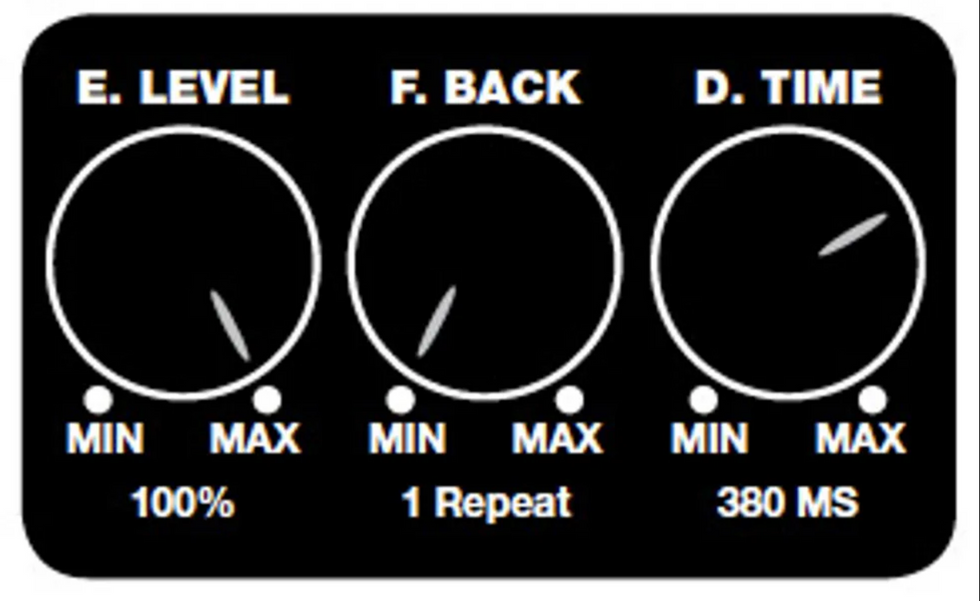

To do this, set your delay to repeat everything you play a dotted-eighth-note (three 16ths) after you play the original note, and then pluck continuous eighth-notes. After the delay's initial entrance on the last 16th of the first beat, it will fill in the second and fourth 16th-note of every successive beat—as long as you continue to play eighth-notes (newly picked notes will cover the first and third 16th of every beat). To make this sound as natural as possible, set your delay pedal's Level knob all the way up so it matches the volume of the original signal, and try to keep the notes as precise and short as you can to avoid having a picked note overlap with a delayed note.

Delays such as the Line 6 Echo Park feature dotted-eighthnote modes that make it a cinch to create rhythmic parts in the style of U2's the Edge or Pink Floyd's David Gilmour.

Some delays, such as the Line 6 Echo Park, have rhythmic subdivision modes built in, so dotted-eighth repeats won't be a problem to set up. However, if your delay doesn't offer subdivisions, you'll have to do some math to get the Time setting right. Here, again, the "Calculating MS fromBPM" sidebar will be a big help.

Delay as Harmonizer

Some delays, such as the Line 6 Echo Park, have rhythmic subdivision modes built in, so dotted-eighth repeats won't be a problem to set up. However, if your delay doesn't offer subdivisions, you'll have to do some math to get the Time setting right. Here, again, the "Calculating MS fromBPM" sidebar will be a big help.

One caveat with using a delay to perform harmonized lines is that you won't be able to easily start both parts simultaneously. You might try using a volume pedal to mute the opening line and bring the volume up when the harmony begins, but the more common approach is to just start a line and opt for a staggered entrance of the harmony line. In fact, some songs were written with staggered harmony parts. For instance, the intro to Iron Maiden's "The Trooper" has a built-in layered entrance of a harmonized line and can be pulled off by a single guitarist using a delay pedal.

Delay as Harmonizer Example

If you're new to harmonizing, here's a quick overview on creating harmony parts. Typically, the intervals of a harmony part are fixed (i.e., the part uses the same interval, shifting between its major or minor form to accommodate diatonic notes) throughout the duration of the line, with thirds and sixths being the most common choices (although fourths, fifths, and octaves are also frequently employed). Of course, there are exceptions to every rule, and different intervals can be used throughout a line. For a more in-depth exploration of harmonized lines, consult a book such as A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony: Music Theory for Real-World Musicians by Jim Aikin or David Baker's Arranging and Composing for the Small Ensemble: Jazz, R&B, Jazz Rock, an advanced workbook with a forward by Quincy Jones.

Looping

Guitar legends such as Bill Frisell and David Torn have made looping an integral part of their live shows. At its most extreme, looping is almost like real-time multi-tracking: You can continually add layers of sound, starting with a bass figure, then a layer of chords, followed by a muted, single-note rhythm part, and then a solo on top. Pedals like the Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler (street $236), Boss DD-7, and Eventide TimeFactor (street $399) have built-in looping functionality and are good options for getting started with looping.

Many newer digital delays—including the Eventide TimeFactor (above), Boss DD-7, and Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler (bottom) —also feature built-in looping functionality.

One tricky thing with looping is that the start and end points of the loop have to be rhythmically precise: When you first record the loop, you have to start the loop on the first beat of the phrase, beat occurs again—thus cutting off the note's sustain to avoid overlap. In every loop, the last note will immediately flow into the repetition of the first note. Sometimes there might be a very slight lag before the effect is actually activated after you step on the pedal. We're talking milliseconds here, but you might feel it and may have to adjust the timing of your stomps accordingly.

If the maximum looping time available on your delay device is too short for some of your more ambitious looping applications, there are still good uses for it. For example, if you only had enough delay time to have one harmony or drone note sound, you could leave it on for infinite feedback and practice playing and hearing scales or patterns against the fixed tonal center. You could also use it to loop a note that you could tune the rest of your strings to if you don't have a tuner (at least you'd be in tune with yourself!). These may not be performance-critical uses, but they could certainly be helpful in your development as a musician.

Adventure Awaits … Awaits … Awaits

Although we've explored its most common uses, there are still many more sounds and textures that can be created with a delay pedal—in fact, the possibilities are nearly endless. And whether you arm yourself with a basic echo box or one of the newer units with a bunch of bells and whistles, learning to see and use the effect in a fresh new way— just as the Edge and Eddie Van Halen did—could make you the next sonic innovator whose sonic weapon is the delectable delay.

Calculating MS from BPM

A song's tempo is usually expressed in terms of beats per minute (bpm). But figuring out a song's tempo by counting beats for 60 seconds isn't especially practical. A more efficient way is to find a smaller multiple of 60 and use that as the basis for your calculations. For example, you can count how many beats go by in 15 seconds and multiply that by 4 (15 x 4 = 60 seconds or one minute) or you can count how many beats go by in 10 seconds then multiply that by 6. It can be hard to get a really accurate reading with this approach, but it will get you in the ballpark, if you're in a pinch.

However, while most musicians think of tempo in terms of bpm, most delay units represent delay time as milliseconds (ms). Studio guitarists used to carry conversion charts in their gigbags to make sure they could always lock in with tempos at a session, and we're including one for you below. If you ever find yourself in need of a beat-matched delay but don't have this chart handy, you can use some basic formulas to convert the desired bpm into ms and set your delay accordingly. The basis for the formulas is the number 60,000—the number of milliseconds in a minute. To convert bpm to ms, the formula is:

60,000/bpm = quarter-note ms

For example, 60,000/100 bpm = 600 ms. If you're playing to a track that is 100 bpm, you'll need to set your delay at 600 ms to get quarter-note repeats.

To get smaller subdivisions of the quarter note, there are two approaches. You can divide the quarter-note ms reading proportionately, as needed. For repeats in eighth-notes, divide the quarter-note ms by 2, and for repeats in 16ths, divide the quarter-note ms by 4. At a tempo of 100 bpm, quarter-note repeats are 600 ms, eighth-note repeats are 300 ms, and 16th-note repeats are 150 ms.

Or you can use these formulas:

30,000/bpm = eighth-note ms

15,000/bpm = 16th-note ms

For triplet-based music, the formula is:

40,000/bpm = quarter-note-triplet ms

For example, 40,000 divided by 100 bpm = 400 ms. You can divide the quarter-note-triplet ms reading to get values for eighth- and 16th-note triplets. To get eighth-note-triplet repeats, divide the quarter-note-triplet ms by 2, and to get 16th-note-triplet repeats, divide the quarter-note-triplet ms by 4. At a tempo of 100 bpm, quarter-note-triplet repeats are 400 ms, eighth-note-triplet repeats are 200 ms, and 16thnote- triplet repeats are 100 ms.

Or you can use these formulas:

20,000/bpm = eighth-note-triplet ms

10,000/bpm = 16th-note-triplet ms

To calculate ms for dotted-eighth-note rhythmic repeats,

the formula is:

45,000/bpm = dotted-eighth-note ms

For example at 100 bpm, you will need a delay time of 450 ms to get repeats in dotted-eighth-notes.

[Updated 8/30/21]