While there’s been a lot of debate about the role of tonewoods in producing an electric guitar’s core sound recently—well, maybe for the past 75 years—nobody’s contested the importance of pickups.

These devices made of magnets, wire coils, and bobbins have their own distinct magic, and choosing the right pickup to create your sound is a big deal to almost every guitarist, but especially to higher-profile working players who need to dependably recreate their ideal tone every night, for the simple reason that it’s the aural representation of their musical soul.

So, we asked five 6-string heavyweights about their favorite pickups. Some talked about their signature models—cultivated to their tastes—and others about classics and their modern variations. We also dipped into acoustic-guitar amplification with a rising star of instrumental folk music. But let’s start with one of the world’s most prominent guitar collectors, who is also the reigning king of blues rock.

Joe Bonamassa

Joe plays his astonishingly clean 1950 Broadcaster.

Joe Bonamassa 1950 Broadcaster Set ($310 street)

Think of legend-in-the-making Joe Bonamassa as a pickup archaeologist. The vintage gear hound is always sifting through the sands of guitar acquisition, looking for good bones. And while nearly every part of a 6-string has an impact on overall sound, think of the pickups as the femur—the main support of great tone.

Like an archaeologist, Bonamassa often makes his finds available to the public, as evidenced by the many classic instruments that have been reproduced as his signature models, and by those sonic femurs—the sets of pickups—that bear his name. His line of Seymour Duncan sets include the Bludgeon ’51 Nocaster, the Blonde Dot 1960 ES-335 humbucker, the Cradle Rock ’63 Strat, the Bonnie 1955 hardtail Strat, and the Amos Flying V humbuckers—all bearing the appellatives he’s given to the special instruments that they hail from—plus a signature pair based on the hummers in one of his 1959 sunburst Les Pauls.

“Some people have signature pickups where they want a certain winding that they want to go into a signature guitar, or some other design they spec out,” Bonamassa says. “I’m not that original. I have a big guitar collection, and each guitar is a little bit different. And it’s like, ‘Why do I play the Nocaster or why do I think the Broadcaster is exceptional?’ It’s because of what’s in it: Not all flat poles and humbucking pickups are created equal.”

It’s natural that the pickup set currently at the front of Bonamassa’s mind is his latest Duncan recreation: his 1950 Broadcaster set from … yeah … his killer 1950 Broadcaster. They have alnico 2 (neck) and alnico 4 magnets, 6.27k resistance at the neck and 8.96k at the bridge, and cloth pushback cable. And while they were resurrected by Bonamassa and Duncan, they were most certainly designed by Leo Fender.

Bonamassa shares his perspective on the pickup development process. “I’m not swapping pickups in my original Broadcaster that’s worth almost a quarter-million dollars, so I always have a ‘donor’ guitar,” he begins. “I have a generic Custom Shop Strat for the Stratocaster stuff, and I’ve got a template Les Paul. In the case of the Broadcaster, Seymour Duncan actually bought a Squier as the test guitar—and that’s the true test. If your Squier sounds as good as that Broadcaster, then we’ve

done our job.”

What does Bonamassa look for in a pickup? “I’m especially interested in the treble side. For humbuckers, I like a higher winding, so it’s a little darker and it barks. Same thing with a flat pole. My favorite flat pole is the one that’s in my Nocaster. It reads at like 9k Leo. And I’m like, wow! It’s just how it was wound in 1951. But overall, if you’re going to really look at pickups, you’ve got to know what they do and don’t do. If you’re talking about a P-90, what P-90 are you talking about? Something that would go into a Les Paul Standard, a Junior? It could sound different in any context. If I need a Junior, I want it all-mahogany and a P-90, right? There’s no putting a set of pickups in a guitar and thinking, ‘Oh, the guitar now sounds magical.’ They have a symbiotic relationship with the wood and with the strings. The great guitars are the ones where you have all the combinations going at once.”

So, what’s the archaeologist’s next “dig?” “I have a Telecaster from ’52 that has an original Paul Bigsby pickup that is pretty exceptional. I really want to see what that’s about.”—Ted Drozdowski

Joe Bonamassa’s signature 1950 Broadcaster pickup set from Seymour Duncan.

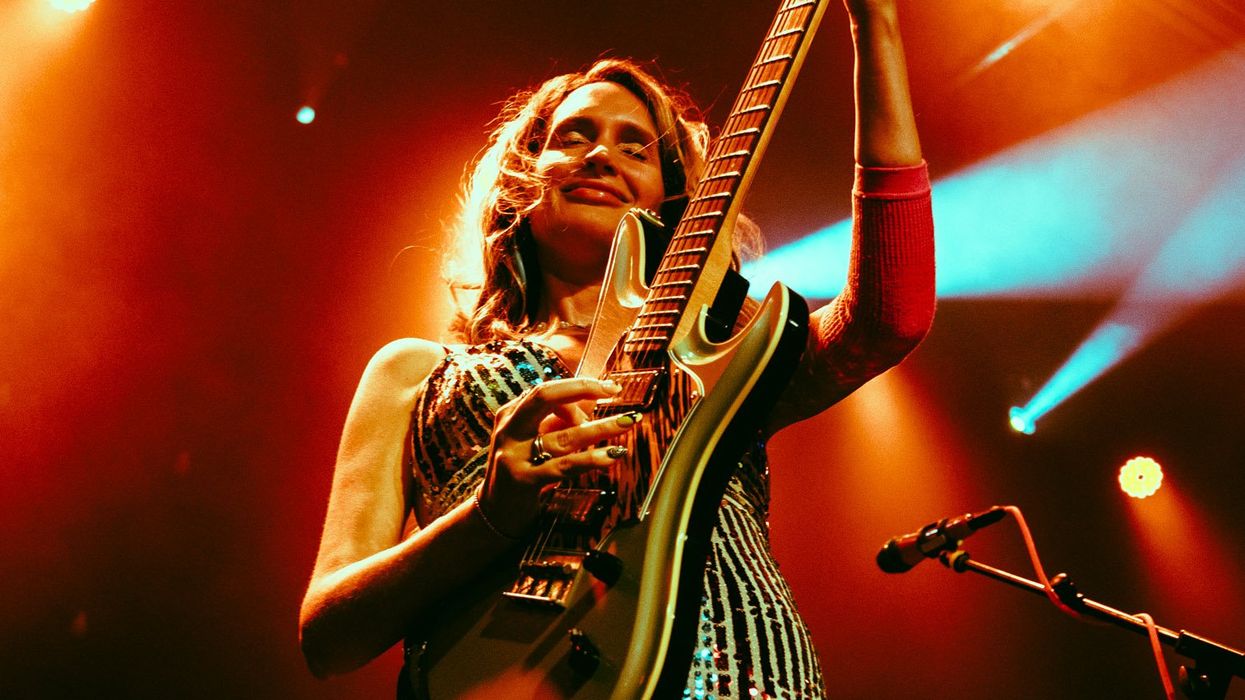

Sadie Dupuis - Speedy Ortiz, sad13

Sadie Dupuis plays her Joe Parker Spectre, outfitted with Lollar Mini-Humbuckers.

Lollar Mini-Humbuckers ($190 street)

Sadie Dupuis’ guitar work probably lives in the realm of alternative rock, but her interpretation and distortion of that genre’s sounds makes her playing an absolute thrill. Speedy Ortiz’s latest record, 2023’s Rabbit Rabbit, is a delightful, freakish outgrowth of bubblegum pop-rock and punkish, arty indie rock; the back-to-back punches of “You S02” and “Scabs” capture not only the band’s wonky, razor-sharp arrangement instincts, but Dupuis’ bonkers breadth of tones, most of which sear and needle through the full-band chaos.

To cover this range of needs and maintain articulation, Dupuis relies on the Lollar Mini-Humbuckers loaded into her Joe Parker Spectre. Lollar’s minis are like a smaller PAF, with one bar magnet positioned under each coil with adjustable pole pieces made out of a ferrous alloy and the second coil containing a ferrous metal bar that is not adjustable—for more bass and more output than an alnico core. Typically their DC resistance at the neck is 6.6k and 7.2k at the bridge. They come with seven different cover options, and there’s a pre-wired kit especially for Les Pauls.

“Since I’m playing leads most of the set, and since I play fingerstyle, I need clear output and sustain that will cut well through the rest of the stage levels and not lose presence,” says Dupuis. “But I also play with noisy pedals, and find the mini humbuckers give a good balance of volume, clarity, and character, without the buzzy chaos of some popular alternatives.” P-90s, for example, don’t get along with her board, but Lollar Imperials, which Dupuis has loaded into her Moniker Anastasia, are another option that deliver the precision she needs.

Dupuis grew up playing Strats, which tuned her ear for a personal guitar EQ that skews brighter, so she appreciates a “somewhat darker-leaning pickup to add body and depth to what could otherwise be a treble overload. A lot of what I’m seeking in a recording environment is a novel sound for that specific moment in that specific track, meaning I’ll pick up guitars I wouldn’t or couldn’t bother with onstage,” adds Dupuis. “Onstage, I just want pickups that can communicate the melodies clearly, reflect my effects transparently, and help the guitar hold its own in tandem with my very loud bandmates!”—Luke Ottenhof

Lollar Mini-Humbuckers

James Hetfield - Metallica

James Hetfield snarls for the camera while extracting huge tone from his EMG Het set.

EMG JH Het Set Active Humbuckers ($269 street)

“Pickups are one of the things that helps an artist make a vision come true,” says James Hetfield, the frontman of heavyweight champions Metallica. “Besides all the crunch and the super-heavy stuff, the clean sound is super important to me … developing a clean pickup that has dynamics. I love the passive pickup, but I love the power of the active pickup, and combining those two things.”

So, over a two-year period, starting in early 2009, Hetfield worked with EMG founder Rob Turner to develop his favorite tone kickers, the Het pickup set. “Rob is the mastermind behind EMG pickups. He’s been working directly with us for all these years. We tried many, many things. He’s the kind of guy that will show up at HQ, listen to what you got, what you want to try—and he put together exactly what I was after. I wanted to have something a little more responsive and lively,” compared to traditional passive humbuckers.

The resulting active Het humbuckers have individual ceramic pole pieces with an alnico bar magnet (which is different from EMG’s famed 81s), the customary ground and hot wiring plus a 9V battery, and employ EMG’s solderless connectivity system. And they come in six cover-color options: brushed black chrome, black chrome, gold, chrome, brushed gold, and brushed chrome. The “Het Set” includes a JH-N for the neck that boasts ceramic poles and bobbins with a larger core, and are taller than EMG’s all-around, multi-style pickup, the 60 model, to produce more attack, higher output, and a richer low end. The JH-B has the same core, but with steel pole pieces. This creates a tight attack with less inductance for a cleaner low end. “This has the old-school look of the old [passive] pickups, and the new EMG heaviness sound,” Hetfield adds.—Ted Drozdowski

A black chrome set of Hetfield’s EMG signatures.

Yasmin Williams

Multi-faceted guitarist Yasmin Williams, pictured with her Skyrocket Grand Concert.

Photo by Ebru Yidiz

Acoustic: James May Engineering the Ultra Tonic V3 ($249 street)

Electric: Diliberto Pickups Custom SuperClean YW

Yasmin Williams, known for her distinctively buoyant, hopeful, sparkling, instrumental acoustic guitar compositions, has pickups in both her main acoustic and electric guitars that are as uniquely customized to her playing as her approach to her own songwriting.

Williams’ main acoustic is a Skyrocket Grand Concert. It’s equipped with the Ultra Tonic V3 Pickup by James May Engineering. “I think they just sound the best, period,” she effuses, quick to praise the work of the boutique builder. “They have the highest fidelity as far as any pickups I’ve played with on acoustic. They’re crystal clear.”

The Ultra Tonic V3’s setup is a bit involved. It comes with separate sensors to be glued to the underside of the bridge plate under the saddle, and to the far bass corner of the underside of the bridge plate. A circuit board attached to the inner end of the pickup’s jack comes with a 12-position balance control switch, which “enunciates different frequencies of your guitar.” During the setup, the guitarist selects the switch position they like best.

Williams’ main electric, an Epiphone ES-339 in Pelham blue, has pickups that were handmade and gifted to her by Hernán do Brito, a luthier for the Buenos Aires, Argentina-based company Diliberto Pickups, after the two released a song together (do Brito performs under the moniker “Dobrotto”). The SuperClean YW pickups set are made with alnico 5 magnets, with 7.9k resistance in the bridge and 6.8k in the neck. Do Brito also hand-painted them to match the pattern on a West African-themed shirt of Williams’.

“They’re pickups designed for a very clean tone, since I do a lot of tapping,” Williams explains. “There’s no muddiness; the tone is really bright—kind of high-end, but not screechy. They’re really good for math-rock type things, and they also play really well with pedals. They sound great with reverb; they sound great dirty, especially if you have a good overdrive. It sounds really good with Plumes, for example, by EarthQuaker Devices. I’ve never had pickups that sound as clear as these do. No noise, no nothing.”

—Kate Koenig

There is only one SuperClean YW pickups set, seen here in Williams’ Epiphone ES-339, made by luthier Hernán do Brito specifically for her.

Nels Cline - Wilco, solo, etc.

Few artists straddle the worlds of rock and experimentalism as well as Cline, and his tone is always killer.

Vintage Jazzmaster Single-Coils/Seymour Duncan Antiquity Jazzmasters ($238 street)

Throughout his work with Wilco and his far-reaching solo projects and collaborations, guitarist Nels Cline is often called upon for anything from warm jazz to overdriven rock to twang to explosive noise. And though he can be seen with quite a collection of instruments in his hands, ultimately, he says, the Jazzmaster “is my favorite guitar.”

“The way the Jazzmaster is designed is perfect for me,” he explains. That fondness extends to their pickups: “There’s the tonal variation of the two pickups with the rhythm switch that nobody but me seems to use, which is my instant jazz tone. Then, there’s the pickup-selector toggle-switch tones, and those are excellent.”

Cline most notably calls upon a pair of vintage models: his early 1960 Watt Jazzmaster, which he keeps in Chicago—so named because he purchased it from bassist Mike Watt—and his New York Jazzmaster. “I believe it’s an early ’59,” he says. Both maintain their original pickups. But the guitarist owns other Jazzmasters and some “fake ones,” and he points out: “If I have to put different pickups in one of my Jazzmasters, I put Duncan Antiquity pickups in them because Seymour Duncan understands what Jazzmasters are supposed to sound like, at least to my ear.”

You may already know this, but Jazzmaster pickups are unique among single-coils. They resemble P-90 soapbars, but unlike the P-90, which has magnets under its coils, the pole pieces in Jazzmaster pickups are, themselves, magnets. They also have flat, wide coils—so-called “pancake windings”—that yield a warmer, fatter tone. And they are reverse-wound, so the middle position yields hum-canceling. Duncan’s Jazzmaster pickups use alnico 2 magnets. They have a hearty 8.2k DC resistance in the neck and bridge.

“I wouldn’t put anything different in a Jazzmaster unless I had to mitigate 60-cycle hum,” he adds. And there are a host of options today, ready to tackle the job, that fit Jazzmasters and maintain the look while secretly containing alternative pickups under their covers. “I’ve done that with Duncan PAFs that look like Jazzmaster pickups,” says Cline. If he has a more specific request, Cline calls Bob Palmieri of Chicago’s Duneland Labs for a custom set. Cline says, “He’s a total genius.”

—Nick Millevoi

Up close and personal: a look at the pickups in one of Cline’s prized vintage Fender Jazzmasters.