Jimi Hendrix is often remembered as a wild, bluesy, lead guitarist who left audiences awestruck with his mind-blowing solos and use of feedback. Still, he had another overshadowed ability that was just as integral to his sound: rhythm guitar playing. When it comes to playing rhythm and blues, soul, and elements of funk, the influence of Hendrix's rhythm style can be heard in clubs, arenas, and recording studios every day.

This rhythm style was really the backbone of his playing, and it was honed through years of working as a professional guitarist backing up Little Richard, the Isley Brothers, and King Curtis. While in these bands, Hendrix developed an ability to create inventive guitar parts that would not only meld into the rhythm section with a deep groove but also push along the energy of the song.

Hendrix had to play behind singers in these settings, and this is where he really developed his unique rhythm approach of ornamenting chord progressions in between the vocals. While Hendrix didn't create this style, he adapted and evolved it out of the popular contemporary soul music of the day. Hendrix was influenced by players like Cornell Dupree, Curtis Mayfield, and Steve Cropper, to name a few. He borrowed ideas from the way Mayfield would play lyrical melodies off the chord shapes. Hendrix adapted the Mayfield approach but made it more about the inventiveness of the rhythm rather than subtle embellishments to the chords. Along the way, Hendrix took it to a whole other level.

Throughout Hendrix's rhythm you can also hear borrowed ideas from Cropper, specifically his use of double-stops, bass lines, and sliding sixths within a rhythm part. Cropper, of course, demonstrated this type of rhythm style all over the classic Stax band recordings out of Memphis. Check out Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, and Eddie Floyd and you'll hear this.

Convert to Thumb

To get started playing in this style, the first thing you have to do is free up fretting-hand fingers within your chord shapes if you want to play the embellishments and ornament the chords the way Hendrix did. Unfortunately, this is where traditional electric guitar barre-chord shapes fall short. So, you'll want to start by converting these major and minor bar chord shapes to thumb chords.

Hendrix would wrap his fretting-hand thumb around the top of the guitar neck and, at times, play the 6th and even 5th string with his thumb. This may seem tough at first, but your hands will adapt over time to these chord formations. You never want to force a chord shape. Lightly go for the shape and then relax your hand. I would recommend starting with a smaller-necked guitar. Hendrix was known for his use of the Fender Stratocaster. These guitars typically have pretty slim necks, which definitely helps make these thumb chord shapes easier to reach.

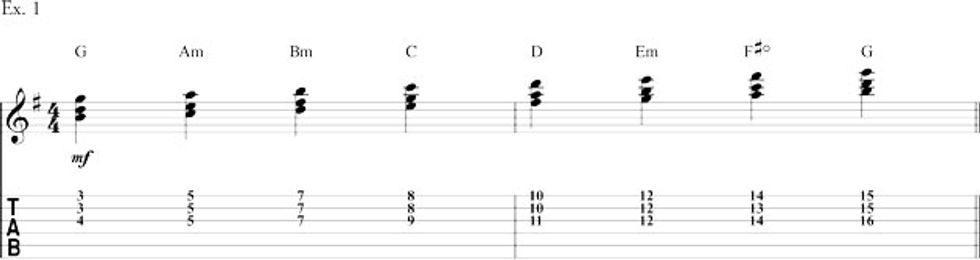

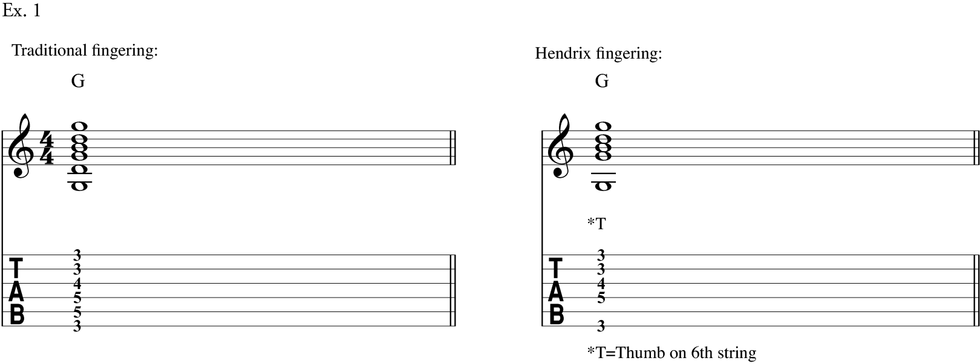

Ex. 1 starts with a typical "E" shape barre chord that has a root on the 6th string. The first chord shape is the traditional fingering, while the second is Hendrix-style with the thumb on the root note.

With the Hendrix thumb-chord shape you have your 4th finger free on your fretting-hand. Now, you are ready to try some embellishments off of the chord shape like Ex. 2. This example uses a classic Hendrix-style hammer-on/pull-off combination with a bass-note pattern that plays independently of the upper melody. This was a key feature in Hendrix's style that, at times, made him sound almost like a piano player. As you play it, try to keep as many notes sustaining and ringing out over each other as possible.

Ex. 2

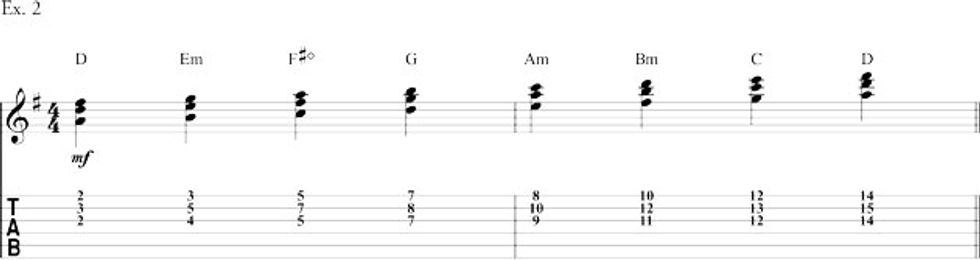

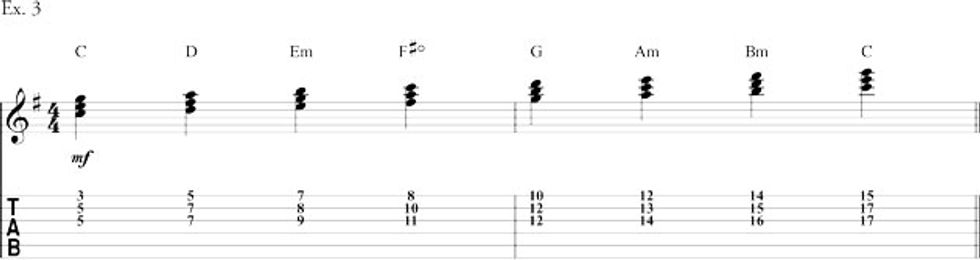

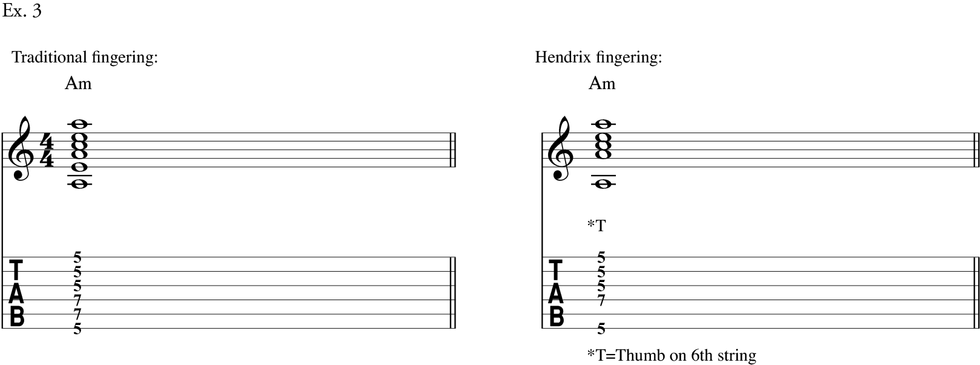

Now, let's see how this can apply to a minor barre chord with a root on the 6th string. We'll start with a minor "E" shape at the 5th fret before converting to a Hendrix style in Ex. 3.

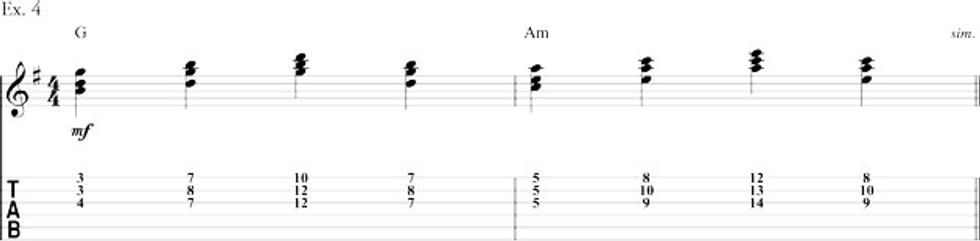

Ex. 4 shows the same concept as Ex. 2 but uses the notes Hendrix would typically gravitate toward over a minor chord shape.

Ex. 4

With Ex. 2 and Ex. 4 you have a small melody using hammer-on and pull-off combinations. However, using your own personal taste, you may decide to use just one or two of these string embellishments at a time within a musical phrase. The point here is give you as many options as possible that are easily accessible off the chord shape. Hendrix would often reach up from any note in the chord and use the next scale degree for ornamenting. Sometimes the scales he would derive the melody notes from were typical major and minor scales, but he would often rely heavily on the use of pentatonic scales and, of course, the blues scale.

Chords with Roots On The 5th String

Now that we have major and minor Hendrix-style moveable chord shapes with roots on the 6th string, let's take a look at a few other must-know Hendrix chord shapes with roots on the 5th string.

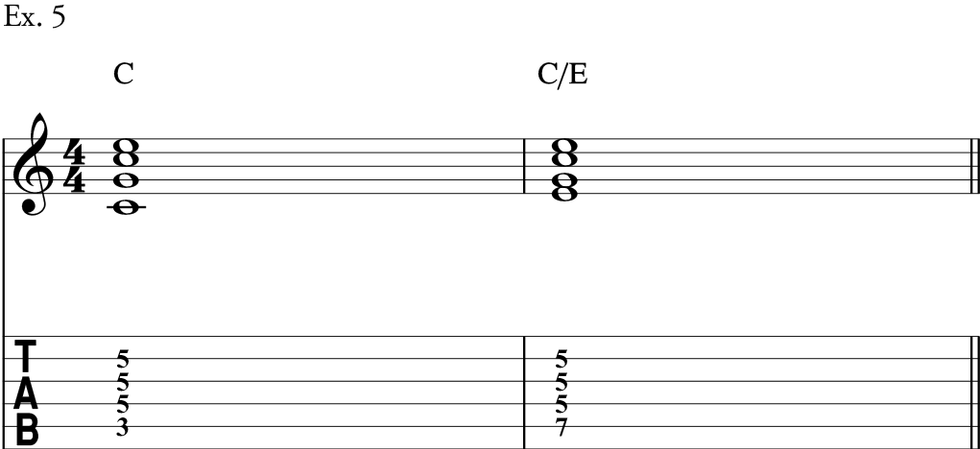

Ex. 5 shows a standard C major barre chord shape with a root on the 5th string. Hendrix used this shape frequently. Often, in context, he would quickly invert the chord up the neck placing the 3 in the bass.

The 3 in the bass creates an optimal fingering for playing double-stop licks off the shape. Ex. 6 demonstrates this idea.

Ex. 6

Slides, Hammer-ons, and Pull-offs

Ex. 7 shows how Hendrix might embellish a standard minor 7 barre chord shape with a root on the 5th string. Notice the same concept of reaching up from a note within the chord shape and using the next scale degree for ornamenting. In this example, the scale of choice is E minor pentatonic (E–G–A–B–D).

Again, based on your taste, you may choose to use just one of these hammer-on/pull-off combinations within your own musical phrase. However, you'll find there are quite a few creative possibilities, especially as you start experimenting with re-ordering them or changing the rhythm.

Ex. 7

Now, let's mix a number of these concepts and chord shapes together with Ex. 8 as we play over a simple three chord progression. Notice also one new chord shape, the Bb(add9) that comes in halfway through the first measure.

Ex. 8

Now that you have unlocked a few of Hendrix's go-to thumb chord shapes, and have played some examples using his typical embellishments, find songs in your repertoire where you can start using these concepts to play more inventive rhythm guitar. Have fun!

This article was updated on August 30, 2021.