Everyone has that “one that got away” story, and as a former small-time vintage-guitar dealer, I’ve got more than a few. The blue-chip examples that passed through my hands haunt me, but there were others that just spoke to my soul. I have fond memories of the hunts, catches, and the releases. Even the ones beyond reach or missed opportunities were exciting. Still, there was one encounter that sticks out maybe more than all. In fact, it led to my 50-year-and-still-counting stint as an instrument builder.

In the late 1960s, the Sound Post was a guitar shop in Evanston, Illinois, not far from where I lived. The owner, Rudy Schlacher, was a former violin maker who had cut his retail teeth at Chicago’s famous Guitar Gallery in the early 1960s before opening his own shop. One of my high school buddies, the late Greg Bennett (designer and founder of Greg Bennett Design) worked at Sound Post, so naturally, I was a familiar face in the store. Schlacher was always trying to entice customers to purchase music gear in novel ways and was the first person to extend store credit to me—a blessing and curse.

One day, while perusing the shop’s usual fare, I noticed an odd-looking guitar hanging on the wall. It was a pale yellow color and shaped like a mutant Dorito. The banana-like headstock had a Gibson logo and a sign that read $10,000 in big numbers. This was when a Les Paul Custom sold for $595, so, naturally, I thought it was a joke, but Schlacher wasn’t kidding. He explained that what I was privileged to see was an extremely rare instrument that few heard of, and even fewer had actually seen. I wasn’t sure if he was exaggerating, but he wouldn’t pull it off the wall for me to play. It made a big impression—I was obsessed.

Fast forward a couple years and a thousand life lessons later, I’d learned all about the Gibson Explorer and why Schlacher had put an impossibly high price on his. He didn’t really want to sell it—it was theater. Through the small community of guitar traders, I had made the acquaintance Chicagoan Jim Beach, owner of Wooden Music on Lincoln Avenue on the city’s North Side. Jim was an accomplished machinist and woodworker who made instruments in the back of his small store. He’d been crafting solidbody electrics of his own design but had also made a few Flying V and Explorer replicas as well.

“The banana-like headstock had a Gibson logo and a sign that read $10,000 in big numbers.”

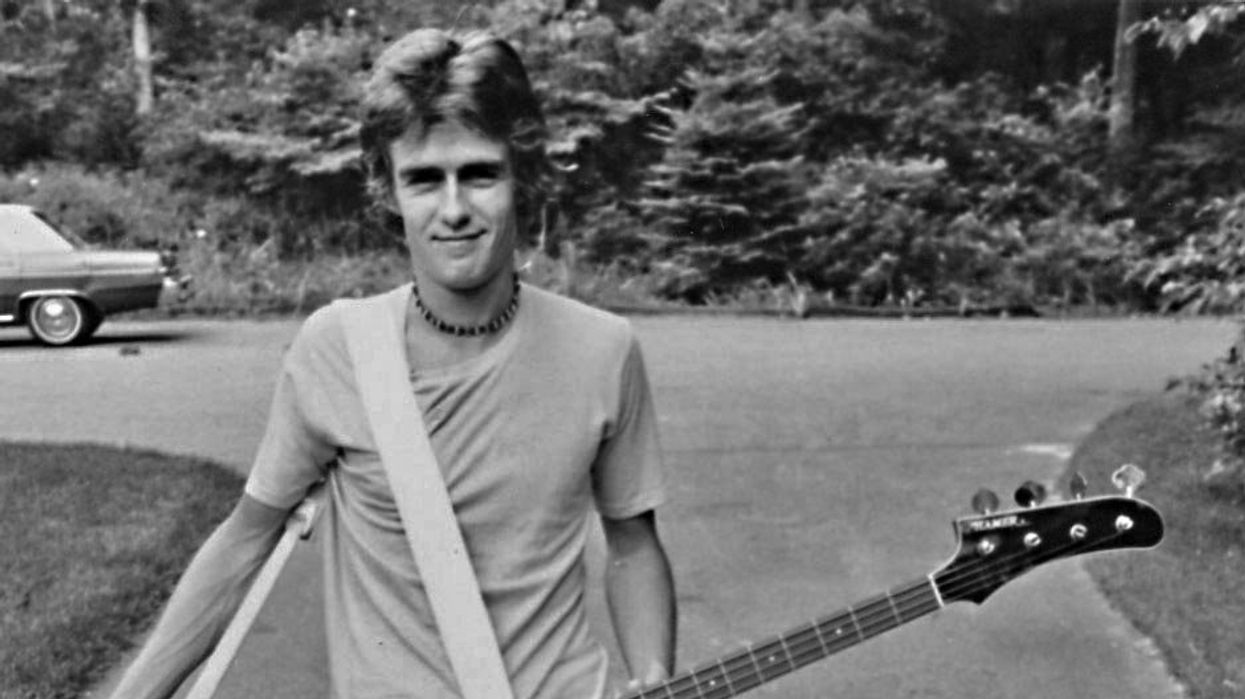

My business partner, Paul Hamer, and I recognized an opportunity to create a hybrid version of our favorite vintage instruments, and we purchased a mahogany husk from Jim in raw state. The previous year, in 1973, we’d created a Flying V bass for me with the help of John Montgomery, a local repair guy who handled our shop’s more difficult jobs, like finishing and neck breaks, in his suburban basement. Montgomery had done some fine repairs on a customer’s Les Paul Standard and had put a flame maple veneer on a Les Paul Professional for the Dutch virtuoso Jan Akkerman, so we had the right ingredients to do something interesting.

What we envisioned was a unique guitar with a bound maple top—a cross between Schlacher’s Explorer and the vaunted ’59 Gibson “Burst.” The mainstream didn’t even know about vintage guitars yet, but that didn’t matter; we knew what we wanted. With some coaxing, Montgomery descended on the Beach husk while we collected the hardware and basically got in his way trying to help in his basement shop. Progress was slow but steady, and by December of 1974, the woodwork, binding, and paint was done at Montgomery’s, so the parts assembly and setup could be completed at our Northern Prairie Music store in Wilmette. We’d put an original PAF humbucker in the bridge position, and the guitar sounded remarkably good. We called it the Standard.

The next day, December 7, 1974, we brought a load of vintage guitars backstage to a Wishbone Ash concert at the UIC Pavilion in Chicago, including the newly minted modern vintage Explorer, which we showed to guitarist Andy Powell. He passed on the guitar, but bassist Martin Turner inquired about having an Explorer bass built. Turner and I sat down with pencil and paper and mapped out the specifics: Thunderbird pickups and bridge, narrow neck, 34" scale, and a gloss black finish with a small amount of metalflake, to look “like the night sky,” as Turner described. As we left the venue, Paul wondered out loud, “How the hell are we going to do this?” I just replied that we’d figure it out, just like we always did. We had our first “Modern Vintage” order, and the rest is history. Even the ones that get away can serve a purpose. And thanks to Rudy, for refusing to let me touch that Explorer.