French-Canadian Steve Hill has been a professional musician since the age of 17. Sometimes as a sideman, sometimes as a frontman, but always onstage with a guitar in his hands and a smile on his face. About 10 years ago, Steve Hill released an album, and it was DOA—it bombed and nothing happened with it (his words, not ours).

"I don't know how to do anything else besides music, so I had to make a living and I own a studio so figured I'll do some solo shows and I'll record a solo album to sell at those shows," says Hill.

That album was called Solo Recordings, Vol. 1 and it's his best-selling record to date. It completely changed his career and it really helped him find his artistic voice. Vol. 1 started out very simple—he sang, played guitar, and stomped his feet. About halfway through that record, he added a kick drum. Then he bought a hi-hat that was used on a few of the last songs recorded for Vol. 1. And for every acoustic song he's recorded, he's used a can of coins tapped to his feet as added percussion.

The success of the Vol. 1 led him to record subsequent albums Vol. 2 and Vol. 3. Each of those records incorporated more and more instrumentation falling on the hands, feet, and shoulders of Hill to pull off both onstage and in the studio. But this wasn't his artistic vision.

"It's all accidents—I never planned for this. I never wanted to be a one-man band [laughs]," says Hill. "125+ shows a year provides a great learning environment. Plus, when I'm not performing, I'm in the studio fine-tuning my approach and working out new material. Everything I recorded for those first three albums was performed live with no overdubs. I wouldn't allow it [laughs]!"

And what's the typical reaction he sees onstage: "Some people are mesmerized, and some people are horrified."

In this episode, the multi-tasking Steve Hill virtually invites PG's Chris Kies into his Canada-based recording studio. The Juno-Award-winning guitarist [Blues Album of the Year (2015)] details why he slides vintage Teisco gold-foils on his holy grail Gibsons and Fenders, explains the evolution of his setup that now covers bass and drums, and proves that one man can get the job done of three.

[Brought to you by D'Addario XL Strings: https://www.daddario.com/XLRR]

All Steve Hill's video, audio, and photos captured and edited by Stephan Ritch.

1959 Gibson Les Paul Junior

No, your eyes aren't deceiving you, that is a true 1959 Gibson Les Paul Junior that was been jerry-rigged with a Teisco gold-foil pickup. Before you start trolling, realize that the guitar has not been damaged or modded in any irreversible manner. When building his solo sound barrage, he specifically sought out the old gold-foils because they slid under the strings without any routing or surgery. And notice how the gold-foil only sits under the Junior's top three strings. (The only thing he had to do was add a stereo output to the Junior so the Teisco pickup hits a bass amp — a 1966 Ampeg B-15 paired with an EHX POG— while the stock P-90 goes through varied combinations of old Fenders.)

Yes, the neck has been broken (five times), but believe it or not, only one occurred while drumming. ("The final punch of a show in Scotland.")

For his Juniors, Hill typically rides with D'Addario NYXLs (.011–.056) and he hasn't used a pick in nearly 30 years. His tunings include D standard, a tweaked open G (D–G–D–G–B–C), and several of the usual-suspect open tunings. And all his gold-foil guitars take a Vovox stereo cable.Close-Up of Hill's '59 Junior

Here's a close-up of the 1959 Gibson Les Paul Junior with its stock P-90 and retrofitted Teisco gold-foil.

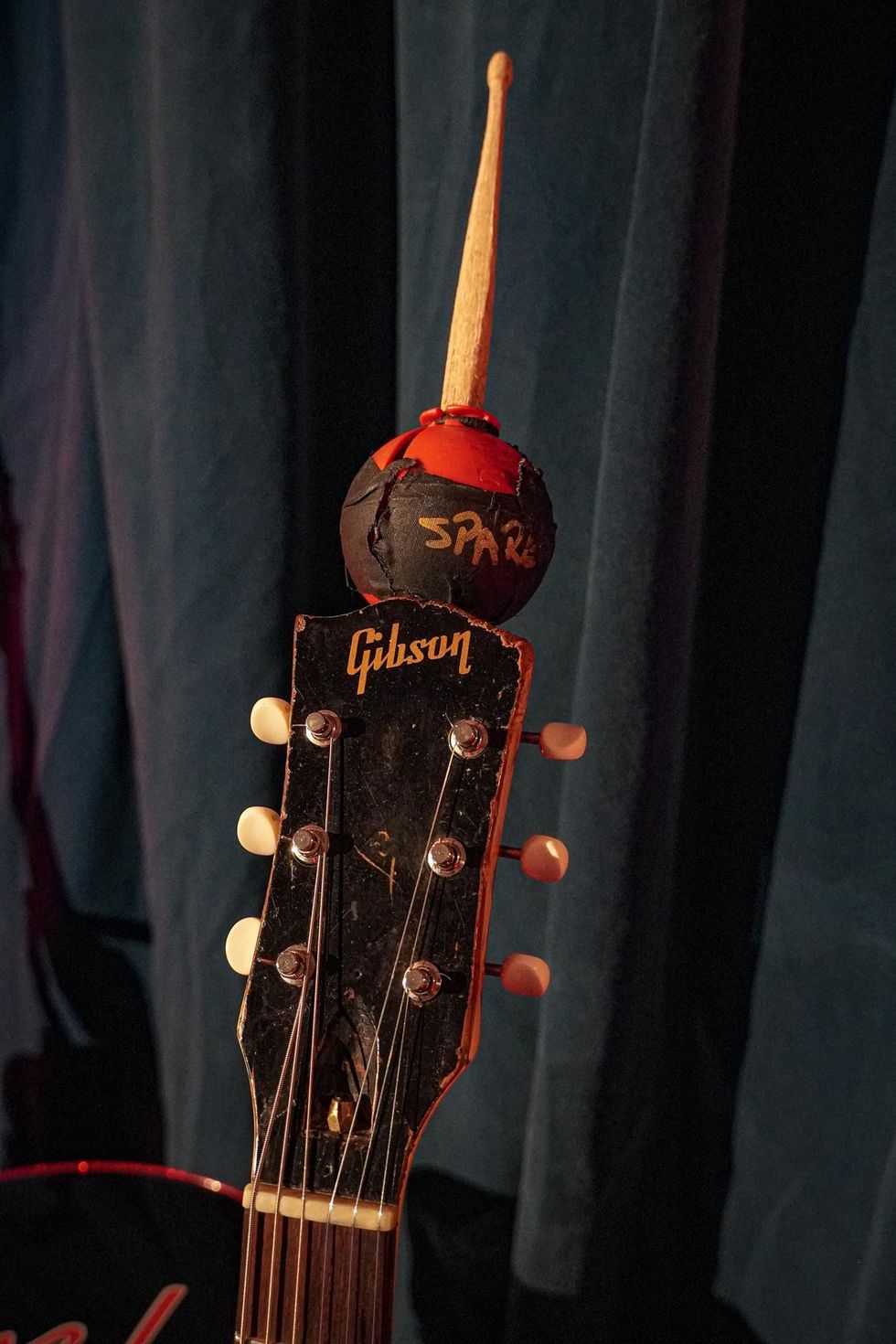

Here's the '59's headstock with a maraca and drumstick.

This is how they fasten to the headstock. Again, no major surgery, Hill just removed the tuners and put the metal plate on the headstock before putting back on its tuning pegs.

1956 Gibson ES-225

This 1956 Gibson ES-225 is where all this craziness started. He primarily used this guitar to record Vol. 1 and the first to feature the P-90-and-gold-foil recipe. (If you look towards the upper bout, you can see residue from gaffer tape that held the Teisco to its top.)

1962 Fender Jazzmaster

"Over the past year, this guitar has become my favorite," gushes Steve Hill when introducing his 1962 Fender Jazzmaster. "After putting a Mastery bridge on it, I don't think I've played a better guitar than this."

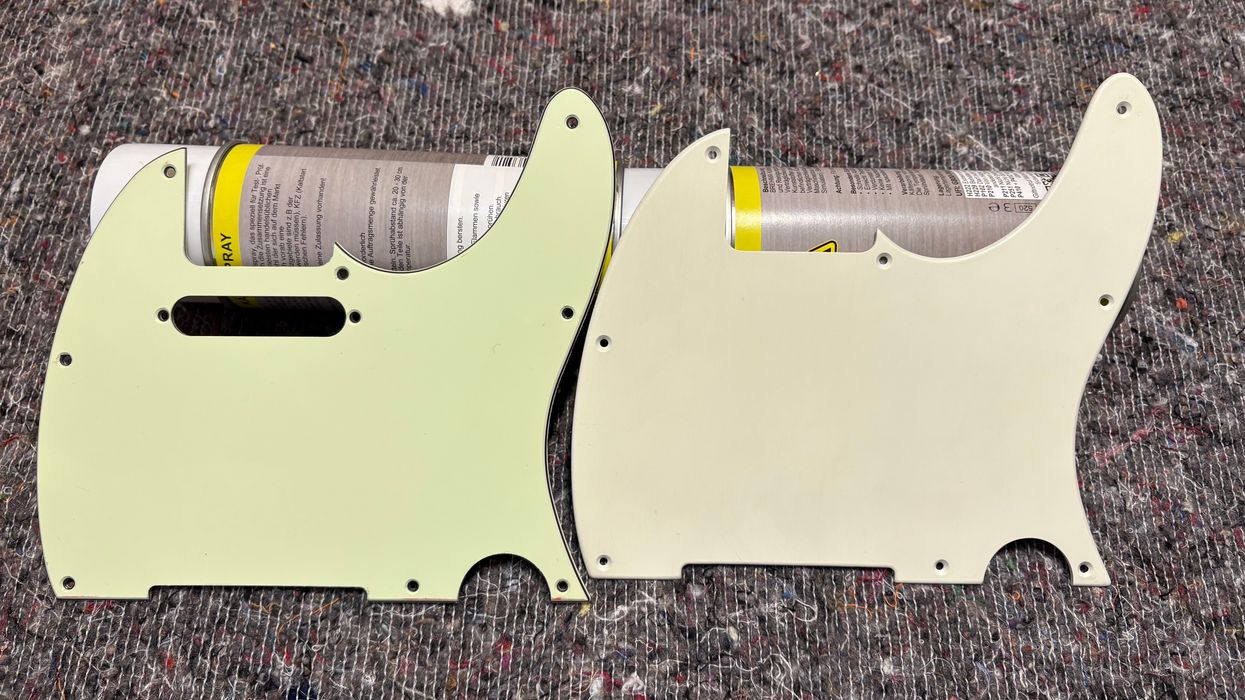

Obviously, we see the gold-foil, but to fit the additional pickup he had to make a custom pickguard. (Rest assured, purists, he still has the original in the guitar's case.)Collings 002H T

"I've had many acoustic guitars, but this is perfection," says Hill when referring to his Collings 002H T. "I've been playing more acoustic guitar and it's absolutely because of this 00 parlor." Since getting it, he's added the Fishman Rare Earth soundhole pickup.

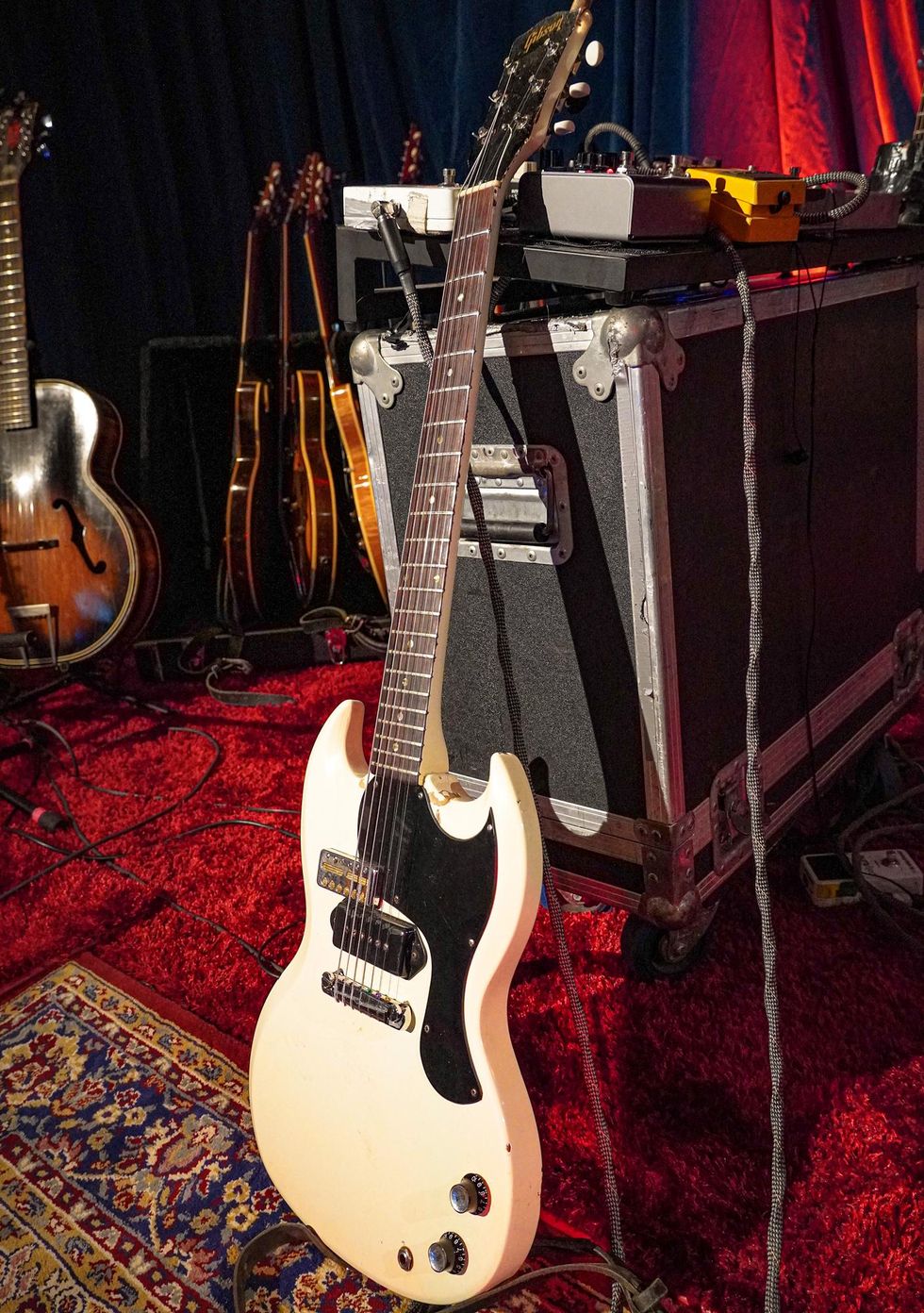

1964 Gibson SG Junior

If it's slide time for Steve, he's grabbing this 1964 Gibson SG Junior. Another consideration beyond tone for Hill is the instrument's weight. If it's too heavy, it throws off his headstock-drumming technique. This one is light and rips, so it's a keeper.

Here is the aforementioned EHX POG that bolsters the bass signal before hitting the 1966 Ampeg B-15. The nondescript box on the right splits the signal coming out of the guitar so he can hit multiple bass and guitar amps.

Steve Hill's Pedalboard

The guitar signal is met with an always-on, three-stage boost blast—Xotic EP Booster, Klon Centaur, and Boss OS-2 OverDrive/Distortion. Hill rides the dynamics with the guitar's volume knob. The EP and Klon are set to neutral settings with only the Klon having the treble and output knobs at noon (while the is gain dialed out). For road work, he opts for a Strymon El Capistan and Source Audio True Spring for delays and reverb. A TC Electronic PolyTune keeps his guitars in check.

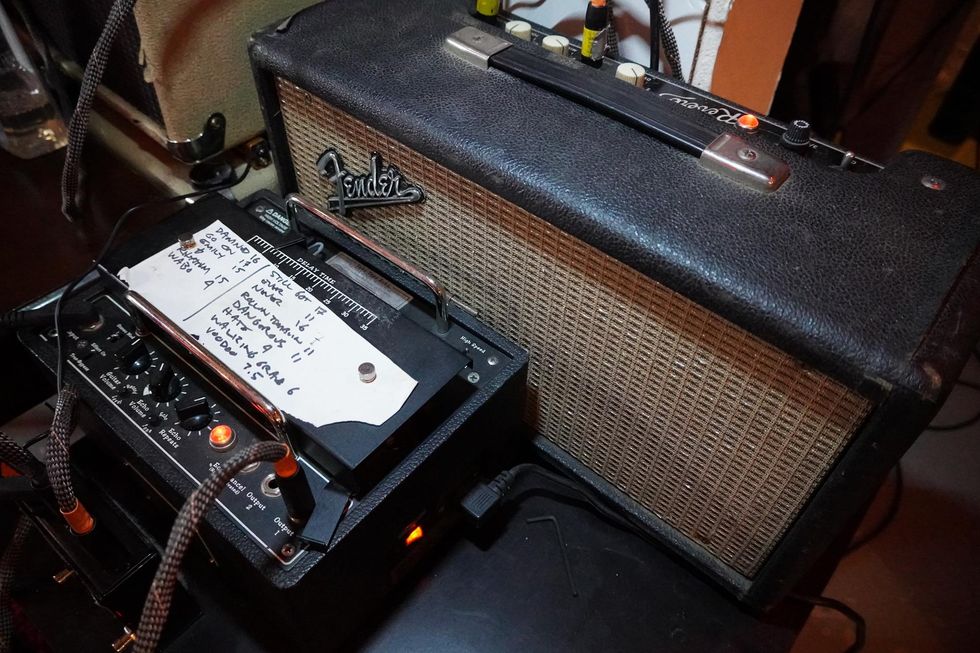

Steve Hill's Studio Effects

For studio work, Hill trusts his tone to a Fulltone Custom Shop Tube Tape Echo CS-TTE and 1964 Fender Reverb Unit.

1966 Ampeg B-15

Here is a 1966 Ampeg B-15 used for Steve's "bass" signal.

Hill's Vintage Fender Combos

A lot of Steve's tone comes from his jaw-dropping amp collection. For the shoot, we were introduced to a 1950 Fender Deluxe (left photos), a 1964 Fender Super Reverb for acoustics (top right), and a 1956 Fender Vibrolux (bottom right and lowest photo).

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)