Songwriter, performer, producer, author, actor, and activist Steve Earle has arguably influenced a paradigm shift in country music. His poetic storytelling mixed with folk, bluegrass, rock, and traditional country has expanded the music's boundaries and made him a pillar of the umbrella genre called Americana.

Before their August 30 sold-out show at Nashville's Ryman Auditorium, Earle and longtime Dukes' guitarist Chris Masterson took me through their touring rigs.

[Brought to you by D'Addario XS Strings: https://www.daddario.com/XSRR]

Holey Moley!

Steve Earle's current No. 1 touring electric is his James Trussart Black Holey Steelcaster. This metal-bodied T-Style features a B16 Bigsby, an Arcane T-style bridge pickup, and an Arcane humbucker neck pickup. And if you can peek through the f-hole, you'll see the ventilated back that gives the guitar its name. This Trussart stays stung with D'Addario XL Nickel Wound Jazz Lights: .012–.052.

Rara Avis

Earle has a long history with Martin Guitars. They released an M-21 Steve Earle Custom Artist Edition a few years ago. Now Steve is touring with two black, custom M-sized Martins that are all mahogany, for better road durability. These are equipped with Fishman's Aura pickup and run into a Fishman Acoustic Guitar Aura Spectrum pre-amp/DI. These Martin's stays strung with D'Addarios, gauged .012–.053. For some tours, Earl plays up to 15 stringed instruments a night onstage.

Mando-tory Playing

Earle's standard mandolin is a Gilchrist, and he also brings this octave mandolin onstage. They're hand-built in Stephen Gilchrist's shop in Lake Gnotuk, Australia. They both take D'Addario strings and, like his electric guitars, go through the same 1/4" cable into his pedalboard. Steve is able to mute/tune, and direct the signal to the amp or DI. He plays Fred Kelly thumb picks—D5J-L-3 Delrin Bumblebee Jazz Lights.

Model Mando

Here's the other custom-made Gilchrist mandolin that Earle travels the world with.

50/50

Two newish, stock Peavey Classic 50 4x10 combos are his stage amps. Earle uses only one at a time, in the normal channel, with input gain around 7 and output volume about the same. The amps face across stage so it's easier on the audience as well as the live audio engineer.

Steve's Settings

Here's what Steve's cooking with on his main Peavey Classic 50.

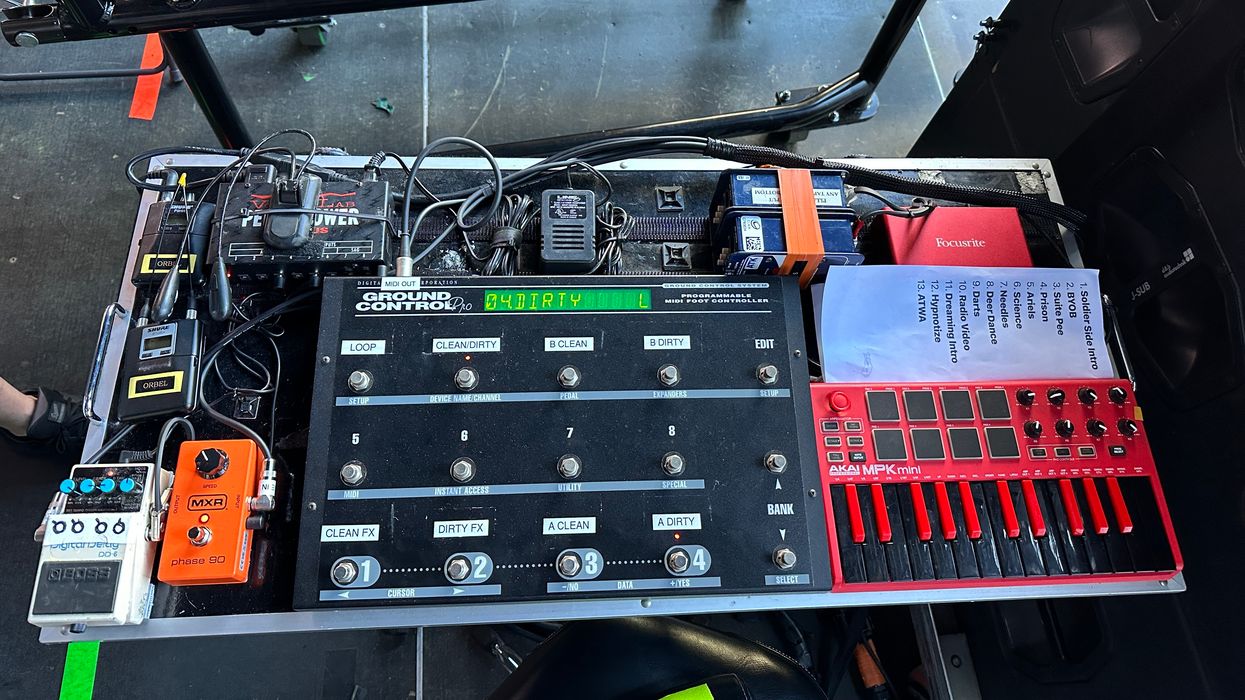

The Chairman's Board

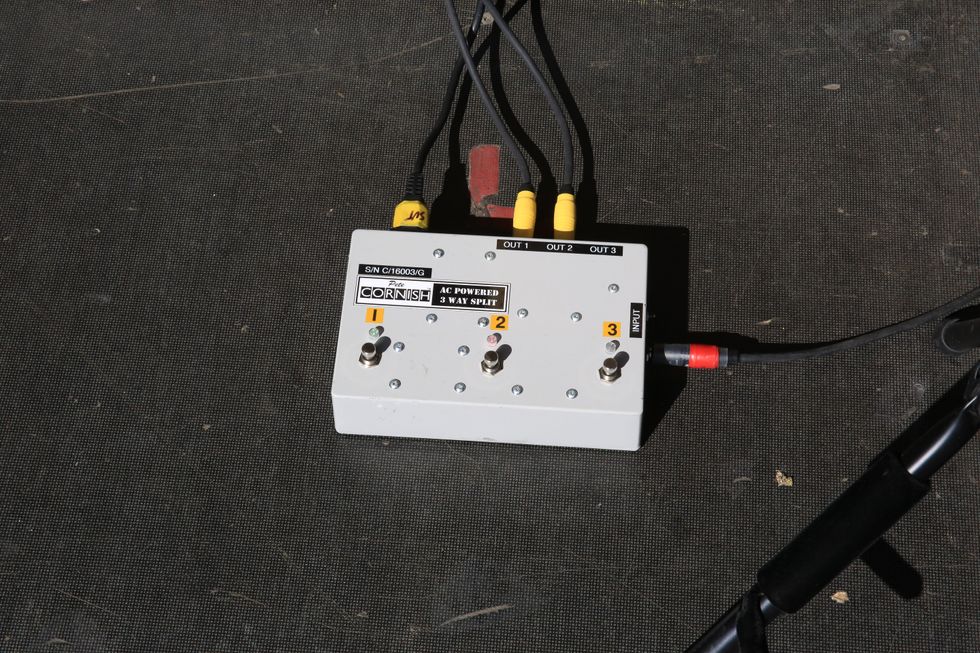

His axes hit a Boss TU-3 and run into a pair of MXR Carbon Copy analog delays (one set as a 1-second delay for a pre-song rippling effect, and one as a slapback/Echoplex), and a Fulltone Full-Drive 2 with two levels of gain. A Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 supplies the juice. Special thanks to tech T. G. "Chief" Frahn for his help on gear details.

Tele Time

Chris Masterson's No. 1 electric is his refinished 1958 Telecaster. The Fender pickups have been changed to some unknown model, but the guitar sounds amazing and Chris has not changed anything else. All of his electrics are strung with D'Addario NYXL1150BT medium tension sets, which run .011–.050.

This Guitar Tries Harder

Masterson's No. 2 is this Fender Custom Shop '57 Telecaster with a Parsons/White B-Bender. Note the original Tele-design bridge on this reissue.

Meant To Be Bent

Here's a look at the routing and mechanism of the Parsons/White B-Bender. Using the device fluidly definitely takes practice.

Hey Buck-O

For humbucker tones, Masterson goes with a Gibson Custom Shop '64 SG with ThroBak ESG-102B P.A.F.-style pickups.

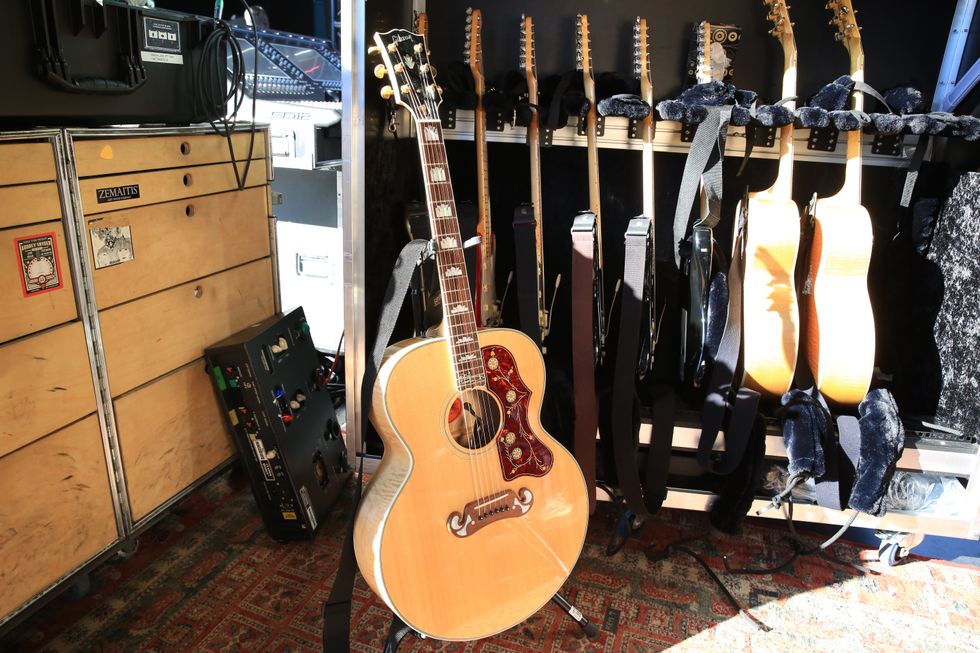

Masterson's Waterloo

This Waterloo acoustic, by Collings, features a Fishman Rare Earth Humbucker soundhole pickup and it is strung with D'Addario NYXLs, gauged .012–.053.

The Low-down

For truly deep twang, a baritone is the right guitar for the job, and this Jerry Jones brings the spaghetti-Western tones when the time is right.

Double Jonesing

The other Jerry Jones onstage is a Neptune 12-string that's also stock. Masterson uses D'Addario heavy celluloid picks on his axes.

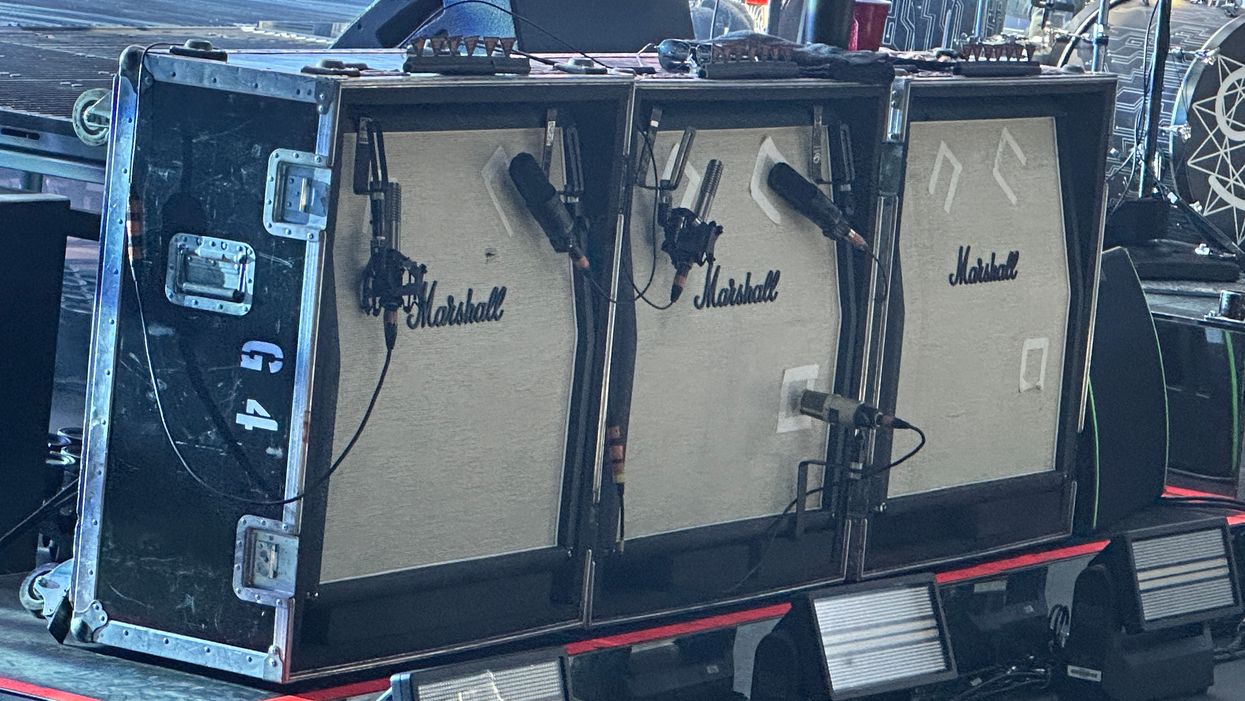

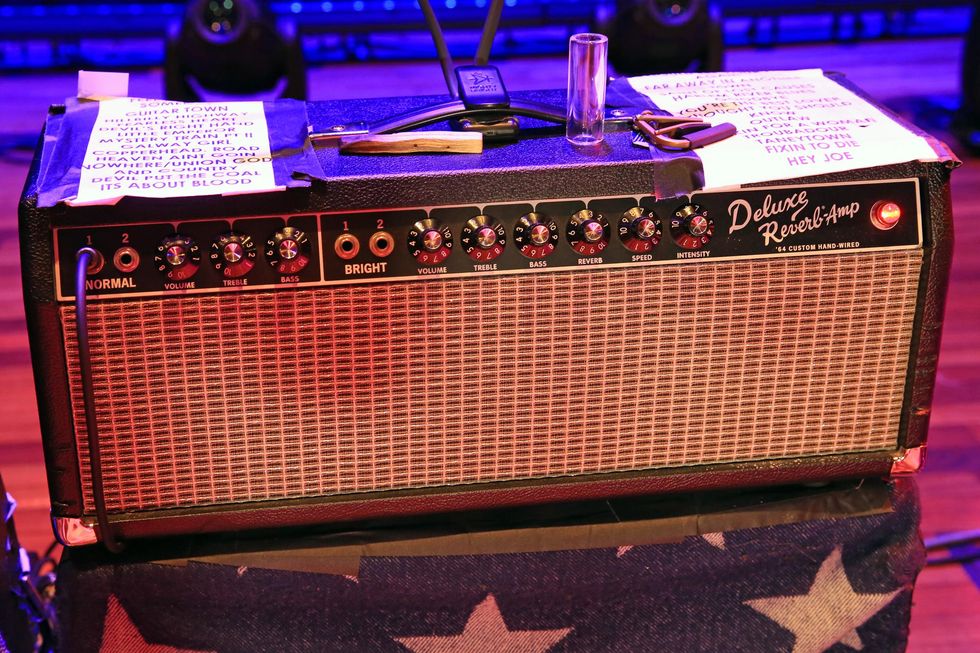

Piggyback Partners

Here's an oddity. This '64 Deluxe head runs a Fender cab with a Mojotone interior that houses a Celestion Creamback G12H-75.

Just for Effects

First stop: an Analog Man Sun Lion. From there the signal hits a Boss Waza Craft Chromatic Tuner, an Origin Effects Cali76 Compressor, an Analog Man King of Tone, a Strymon Mobius, and a Strymon TimeLine. Strymon's Zuma supplies power and a Radial footswitch turns amps and reverb and tremolo on/off. Masterson uses Divine Noise cables.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)