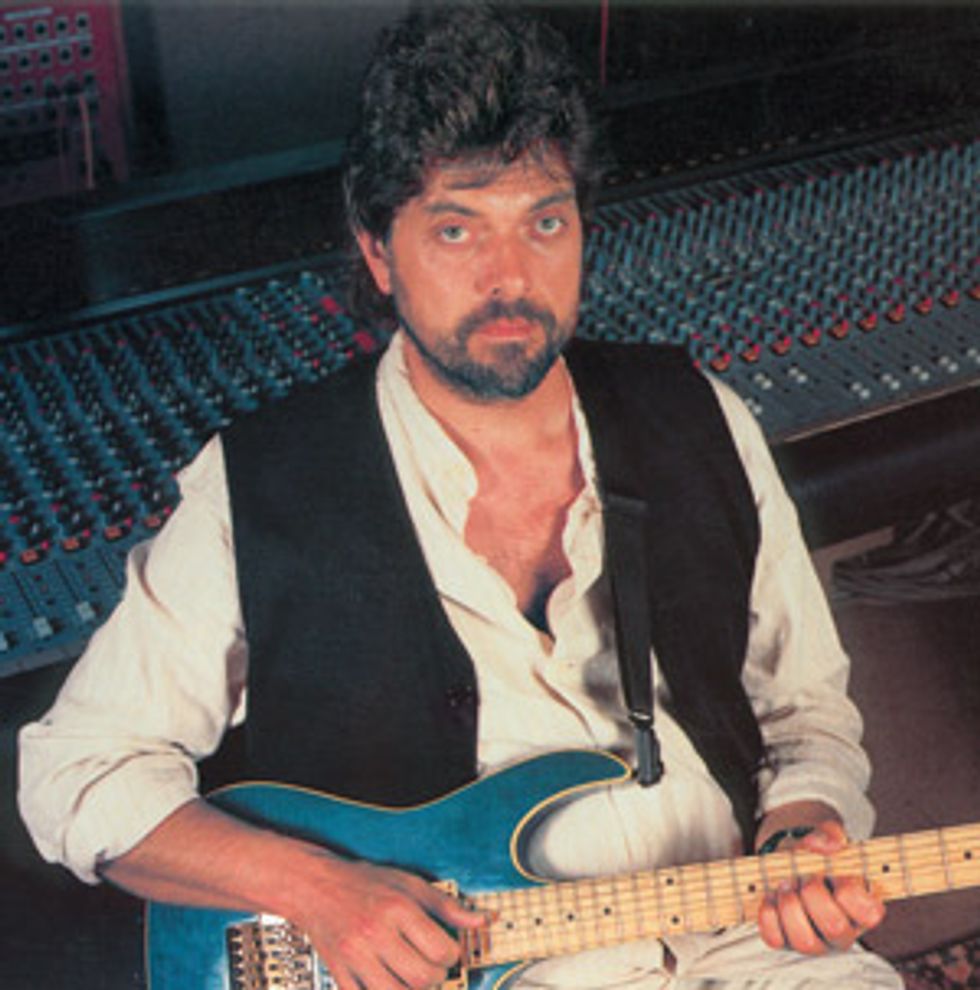

Recording engineer Alan Parsons’ fi rst studio gigs included tracking albums by the Beatles and Pink Floyd.

Imagine, you’re 19 years old, and you’ve landed a job as an assistant engineer at the famous Abbey Road Studios in London. Among your first sessions? The Beatles’ last two albums, Let It Be and Abbey Road. Then, after being promoted to full engineer, you are assigned to work with a band called Pink Floyd on a project called Atom Heart Mother, followed by Dark Side of the Moon—the latter of which earns you the first of nearly a dozen Grammy nominations. Not a bad way to start out, is it?

For Alan Parsons, it was a launching pad for a stellar career engineering and producing a who’s who of recording artists, including the Hollies (“He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother,” “The Air That I Breathe”), Paul McCartney (Red Rose Speedway, Wild Life), Al Stewart (Year of the Cat, Time Passages), Ambrosia (Ambrosia), and many more. But Parsons wasn’t content to stay behind the console. He also stepped out front with his Alan Parsons Project, earning hit records (including I Robot, Eye in the Sky, Stereotomy), and touring the world to soldout crowds along the way. He is an accomplished vocalist, keyboardist, saxophonist, flautist, bassist, guitarist, and songwriter.

These days, Parsons maintains a busy schedule as a producer, and performs around the world with his Project. His latest venture is educating a new generation of engineers and producers with his Art and Science of Sound Recording series of DVDs, web videos, and master classes.

Needless to say, after working with axe slingers ranging from George Harrison to David Gilmour, Alan Parsons knows a thing or two about tracking great guitar tones. Premier Guitar recently sat down with Parsons to discuss his guitar-recording secrets, as well as how he captured the seminal sounds on Dark Side of the Moon.

You’ve captured some of the most

iconic guitar sounds of all time—David

Gilmour’s “Money” tones being one

example. Mics are obviously crucial to

that. In the past, you’ve said you always

use condenser mics on guitar amps, never

dynamic mics. Why?

Dynamic mics tend to accentuate what I

would call “hard” top-end frequencies, like

3 or 4 kHz—and that’s just the area you

generally don’t want to accentuate on an

electric guitar. I’ve always had better luck,

in terms of smoothness, using condensers.

Do you tend to use large- or small-diaphragm

condensers?

I’m comfortable with either, actually.

Historically, I’ve used large-diaphragms

most of the time, usually a Neumann

U 87 or U 86. Somehow, I’ve always

favored Neumann over AKG condensers.

I favor AKG for dynamic mics, but I favor

Neumann for condensers. People often

ask me if I’ve noticed how many new mics

there are out there lately—new condenser

mics, new ribbon mics. I have, but I still

come back to the old faithfuls. I’ve not been

excited by a new mic in a very long time.

Parsons’ recording advice for guitarists: “Never be frightened to add bottom end.” Electric guitar can sound hard and thin, he says, but accentuating the

bass frequencies can help smooth it out.

You’ve also said you avoid close mic placement

on guitar amps. Is that still true?

That’s absolutely true, because if you mic a

speaker of an amplifier in a certain location,

you’re just hearing that part of the speaker,

you’re not hearing the whole speaker. So I’d

say, generally speaking, you’re not getting

the full picture. I think there’s this separation

paranoia that people have with guitars.

They go, “If I don’t stick the mic right on

the cabinet, I’m going to pick up drums.”

The simple truth is that you won’t. It will

be fine—because the guitar is adequately

loud, and anything else is adequately quiet.

It’s not going to be a problem. Even on a

live take, you can go as much as a foot away

without problem. Live sound engineers just

don’t seem to get it.

Is about a foot away from the cabinet

where you start?

Live, I probably start eight to nine inches

away. In the studio, I might even start a

foot and a half, 18 inches away. And I

might go as much as five or six feet away,

depending on how loud it is and whether

it’s a big cabinet with four speakers in it.

You have to start at least 18 inches away to

pick up all four speakers equally.

Because you’re trying to capture the

sound of the entire cabinet.

Yeah, I think if you’re a guitar player, you

hear the whole cabinet—you don’t just hear

one speaker. I’m not saying that’s a rule or

that you might not get a very good result

just mic’ing one speaker. I’m just saying, as

a general procedure, I would want to make

sure that the entire rig is being heard, not

just one element of it.

You’ve also said you don’t use ambient

mics with guitar cabinets. Is that because

you’re pulling the single mic farther away?

That’s a slightly unfair generalization. I

have used ambient mics. I think, especially

if you’re recording guitar with a band, as I

often do, an ambient mic is just going to

reduce your separation. I think outboard

processing of room sounds is usually as

good and more versatile than using ambient

mics. If you want a guitar to sound

like it is in a room, then put a room plugin

on it, y’know? It will sound good, and

you can control how far away that virtual

mic is, or control all kinds of stuff. But it

is a generalization that I don’t use ambient

mics. I just think you get more versatility

by not using them.

Would that hold true if you were overdubbing

a guitar by itself?

Overdubbing is different. It all depends

on the style of music, as well. If the music

calls for an ambient sound, then I put an

ambient mic up. If it doesn’t and you want

the sound in your face, then I wouldn’t. I

think every case is different.

While we’re on the subject, do you recall

what mics were used on the Beatles sessions

you worked on?

I remember on Let It Be, Glyn Johns used

a [Neumann] U 67 on George’s cabinet. I

think Geoff Emerick favored the AKG D19

[on Abbey Road].

What about with Gilmour on Dark Side

of the Moon?

Probably a [Neumann] U 87, possibly a U

86. I’ve carried that through right to the

present day.

Did you use both of those together or

did you use them separately?

Just one or the other. By the time we

got around to overdubs, probably the

only mic I actually had set up would

be a [Neumann] U 47 so that we could

do vocals. I might have stuck that on

it, on occasion.

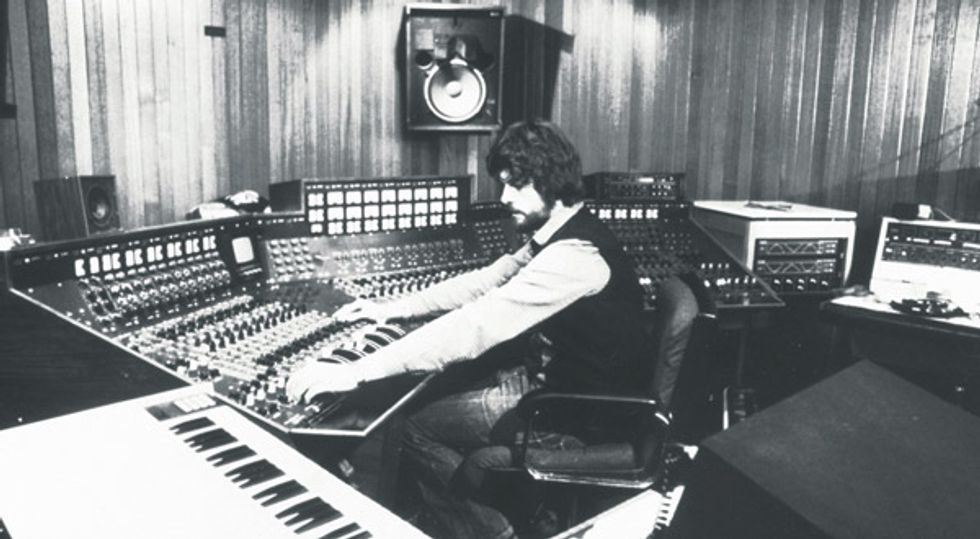

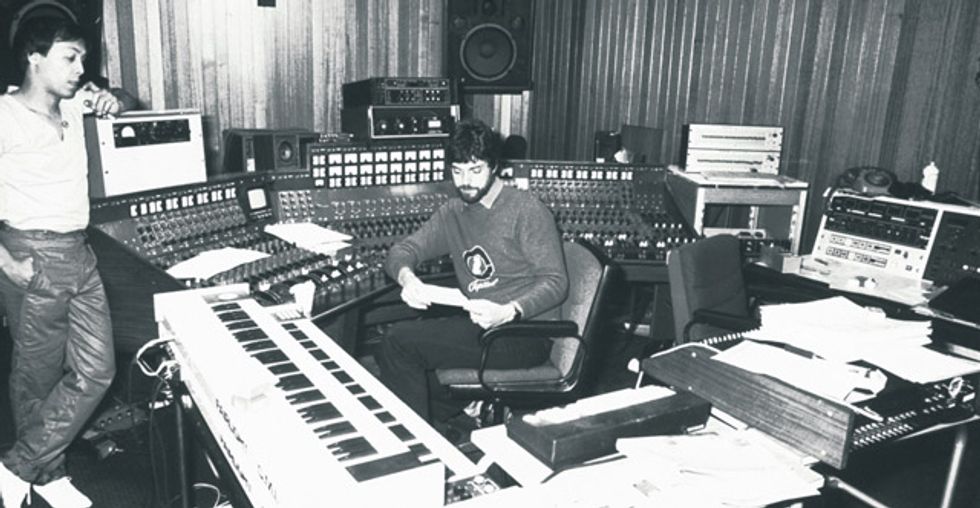

Tracking Floyd’s Dark Side was difficult for Parsons (center) for many reasons, including the fact that they had five or six tape machines set for different delays.

Just because it was convenient?

Yeah. The 47 is a great mic, and it will

record vocals and guitar admirably. I

would not see any reason to dig out an 87

or an 86 for the task. But, you know, the

guitars were recorded over the year that

it took to record that album. A lot of the

guitars were live, and we did a lot of overdubs.

I’d say that there were a number of

different setups.

Were you concerned at all with trying to

match sounds as you progressed through

that year of sessions?

There wasn’t a requirement to do that. I

mean, the sounds between the songs were

so diverse and the styles of the songs were

so diverse, there was no real need to have

any continuity.

Did Gilmour play in the control room

or out in the studio?

It was the first time I’d ever done it

where David was in the control room

with his amp in the studio. I’d never

done that before.

His amp head was in the control room

and the speaker was out in the studio?

No, his whole rig was out in the studio.

So you ran a long guitar cable out to

the amp.

Yes, we ran a long guitar cable, which I

later found out was probably not a good

idea [laughs]. You can lose a lot in a long

guitar cable.

But it worked out okay …

Yeah, it seemed all right [laughs]. The first

thing to go would be top end. We would

have been getting a somewhat mellower

sound through a long guitar cable than we

might have with a shorter cable.

The studio at Abbey Road is a big room.

Most of the guitars were in the number 3

studio, which is actually the smallest—but

it is a big room, yeah. A good-sized room.

How much time did you spend finding

the right place for the microphones on

the amps?

Generally, I’d put a mic out and I might

move it once, but not beyond that. I would

usually get it to a place where I felt it

worked—in theory—and then if it didn’t

work, I’d move it. But I saw no reason to

move it if it was working.

Were you following your “18 inches away

with a 4x12 cabinet” philosophy back then?

Yeah, I would guess so.

Some sources say Gilmour tracked some

of that album with a Fender Twin. Was

that mic’d the same way?

I have no memory of that. All I remember

is a 4x12 Hiwatt cabinet and whatever

speakers were in there. Oh yeah, and a

Leslie. On “Breathe,” for example.

How did you mic that?

Most likely it was fairly distant. Probably

one mic on the top, one mic on the bottom.

Because we were on 16-track, as opposed

to 24-track, I was probably not recording

the Leslie in stereo—because of not having

enough tracks. It would have all been recorded

mono anyway, so it was getting a good

spectral response out of the Leslie, rather

than any kind of stereo out of it.

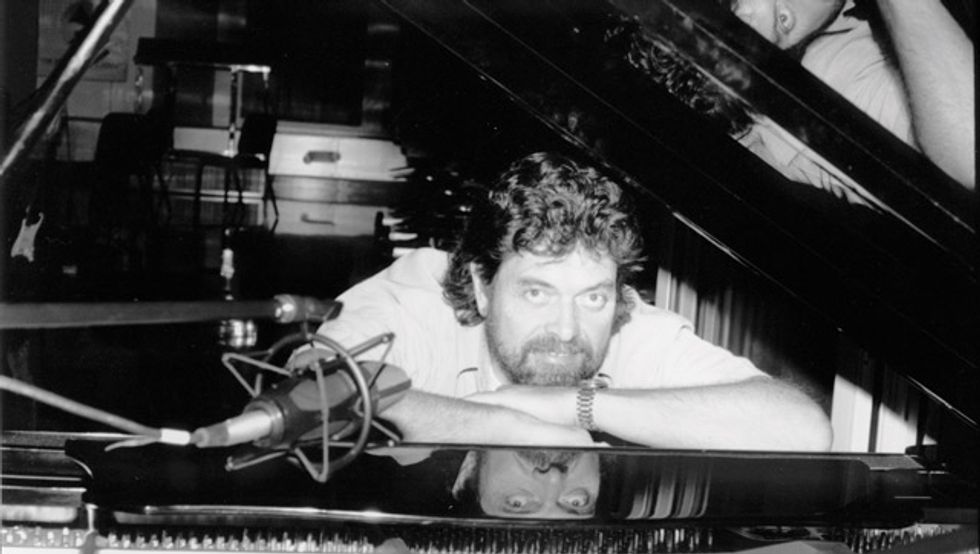

Parsons stands with an array of speaker monitors—two sets of nearfields and wall-mounted mains—that help him optimize mixing adjustments.

Are the sounds that you were capturing

pretty much what we hear on the final

mix, or was there a lot of processing done

at mixdown?

Yes, David tracked with his effects. He had

a pretty advanced pedalboard for the period.

I mean, I don’t know if it was actually

a “pedalboard,” but he had pedals. He had

phasing pedals and wah-wah pedals and all

kinds of things. And there was also a thing

made by EMS called the HiFli, which was

a sort of console device that had an early

form of chorusing on it and some other

effects. It was an interesting box.

You’ve said in the past that you’re not a

big fan of compression, except for managing

out-of-control dynamics. Did you

use much compression on the Dark Side

of the Moon mixdown?

What generally tended to happen was

either no compression or compression on

everything except the drums, because I

totally hate—with a vengeance—compressing

drums. So, although [producer] Chris

Thomas wanted to compress everything, I

talked him into compressing just the instruments

and vocals, but not the drums.

You created some pretty cool sounds with

very little studio gear on Dark Side—

basically, an EMI console, a 16-track tape

machine, Fairchild limiters, and an EMT

plate reverb.

Every sort of time-based process was done

with tape—there were no digital boxes

then. We might have had as many as five

or six tape machines doing various delays,

reverb delays, and so on. I distinctly

remember on the mix having to borrow

tape machines from other rooms to get

delays and stuff.

There were a lot of tape loops, too.

Did you do a lot of actual tape editing

in addition?

Oh, plenty. The 16-track was an edited

tape. You’d think that all the connecting of

the songs was done at the mix stage, but it

wasn’t. It was all there on the master tracks.

There was a break between side one and

side two, just as there was on the vinyl, but

you could play the whole multitrack as a

continuous piece, so everything was there.

You actually did the edits right on the

master recording, the master multitrack?

Yeah. That was a challenge for getting tracks

well played, getting the right instruments in

the right places and not having any problems

at the crossovers [tape splice points].

To do a new take, you had to erase the

old take. So the new one always had to

be better—because you couldn’t click

undo like we do digitally today, and you

didn’t have a bunch of tracks to spare

like we have now with digital audio

workstations (DAWs).

Well, we ended up second generation in order

to make more tracks available. [Ed. Note:

“Second generation” refers to a bounce or submix

from one multitrack tape machine to a second

multitrack tape machine to free up tracks for

additional overdubs.] There were even some

songs, I can’t remember which ones specifically,

where the bass and all drums were reduced

to two tracks on the second-generation tape.

It must’ve been a pretty big challenge to

balance the drums and bass and still have

them sound good when everything else

was laid on top later.

That was definitely a challenge [laughs].

It was, “Oh my God, I hope I’ve got this

right—because I can’t go back!”

Sometimes having limited options is

better than having too many options.

Looking back, do you think those limitations

were somehow an advantage?

Oh, I agree with that totally. There are far

too many decisions that can be made later

now. I’m all for committing at the earliest

possible moment.

Parsons’ advice for going into the studio is to “do the processing at the front end,” focusing on the playing and composition of the music rather

than the equipment.

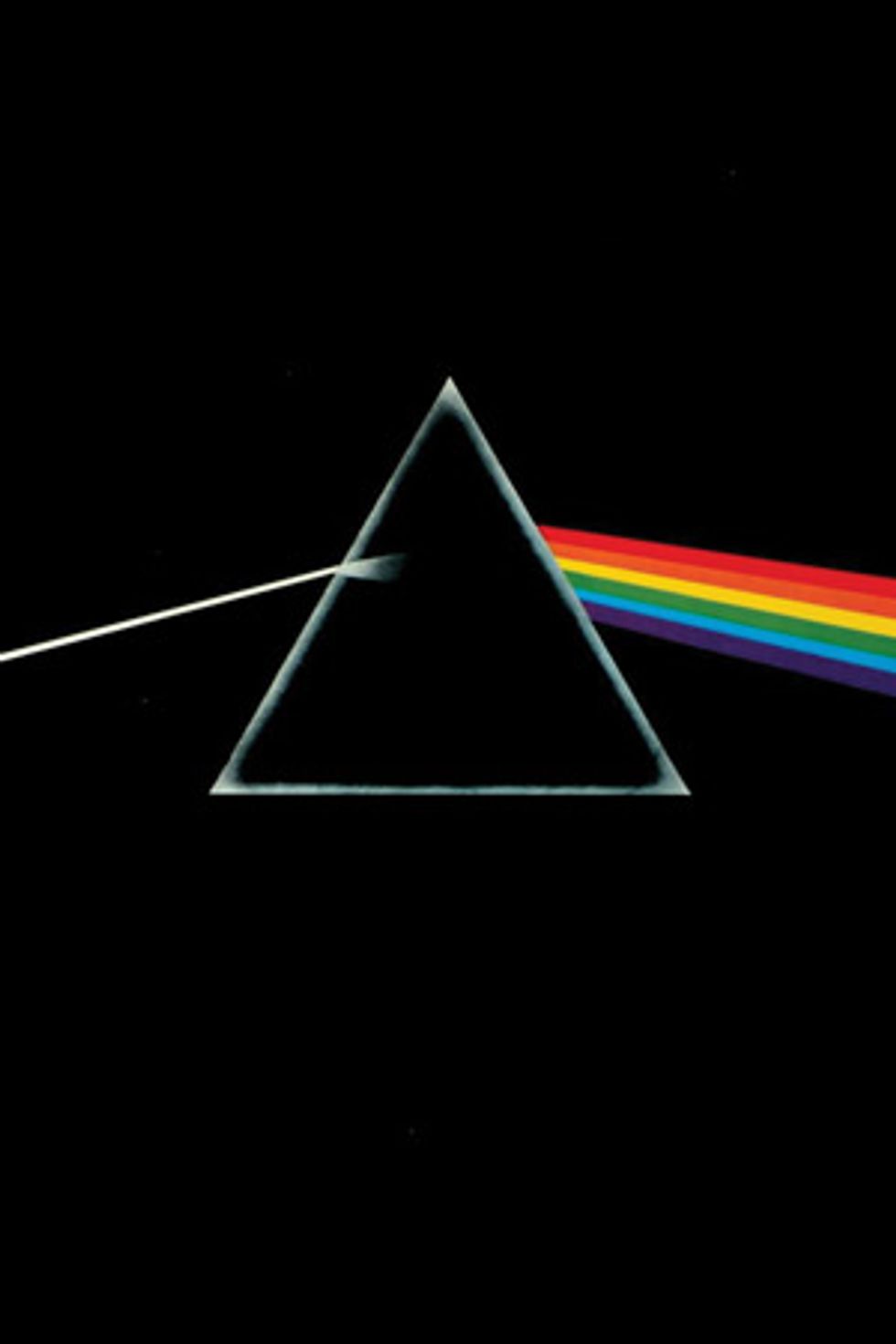

About Dark Side

Pink Floyd had already released

seven albums and was a major success

by the time their magnum opus,

Dark Side of the Moon, debuted in

early 1973. They’d begun working

on the new songs in 1971, and the

suite—which was originally known as

Dark Side of the Moon: A Piece for

Assorted Lunatics—was performed

live for the press in early ’72. Floyd

entered the studio in May of that year,

with Alan Parsons manning the console

and Chris Thomas (Roxy Music,

Badfinger, Sex Pistols, Pretenders)

producing. They spent nearly a year

recording what would become one of

the biggest albums of all time.

Dark Side was an immediate hit upon its release in March 1973. It shot to the top of the charts within a week, and remained on them for an amazing 741 weeks. It is one of the best-selling albums of all time (50 million copies and counting), surpassed only by Michael Jackson’s Thriller. It has been remastered and rereleased several times, most recently as part of the exhaustive Why Pink Floyd…? set released in September 2011.

It’s been almost 40 years since Dark Side

came out, but it’s still regarded by many

as an audiophile master recording. What

do you attribute that to?

I don’t take all the credit. I mean, the band

members were experienced in the studio.

They arguably were the most technically

minded band out there. They knew what

a recording studio was capable of, and they

took full advantage. And they worked me

hard—they always worked their engineers

hard to push the barriers. There’s no better

band for an engineer to cut his teeth on,

frankly [laughs].

What’s your advice for musicians wanting

to capture that quality of sounds in a

home studio or a project studio?

Just get the band playing. Use good mics and

good mic preamps and so on, and then leave it

alone. Do the processing at the front end—in

the playing and in the composition. For the Art

and Science of Sound Recording, we did a master

class at the Village Studios and we got the top

guys: Nathan East [Eric Clapton, Four Play,

Stevie Wonder, Herbie Hancock] on bass, Rami

Jaffee [Wallflowers, Foo Fighters] on keyboards,

Vinnie Coliauta [Sting, Allan Holdsworth,

Frank Zappa, Jeff Beck] on drums, and Michael

Thompson [master L.A. session guitarist] on

guitar. We laid down a track, and it sounded

great with no plug-ins, no special sound processing.

Everybody was just making their own

good sounds. Nathan had his own little pedal

box and Michael had a rack full of gear, so they

made it sound good at the source and then

we just committed it to disk—and it sounded

great. There’s another general attitude that the

more time you spend experimenting and turning

sounds inside out, the better it will get. But

it’s often the reverse that is true.

Any tips for guitarists recording at home?

The technology has evolved. You’ve got all

these Line 6 Pods and SansAmp devices

to get nice distortion out of. But you

know, there’s no substitute for a great lead

sound—like a vintage Les Paul through a

Marshall amplifier. I still think that’s a great

guitar sound—and hard to get any other

way. So much of it is in the playing, as well.

I’m not an electric guitar player—I’ve got a

rig here at home, and when I play it sounds

like utter crap—but when I get a guitarist

in here, he makes it absolutely sing [laughs].

So that makes a huge difference. The standard

of musicianship, quite apart from the

other stuff, is such a huge contribution to

the way a guitar sounds.

Any final thoughts you’d like to add?

I’d just like to add one thing: Never be

frightened to add bottom end if you’re a

guitarist. I often do that. Electric guitars can

sound hard and thin, and rather than try

and remove that hardness, I add some bottom

end on the console to smooth it out.

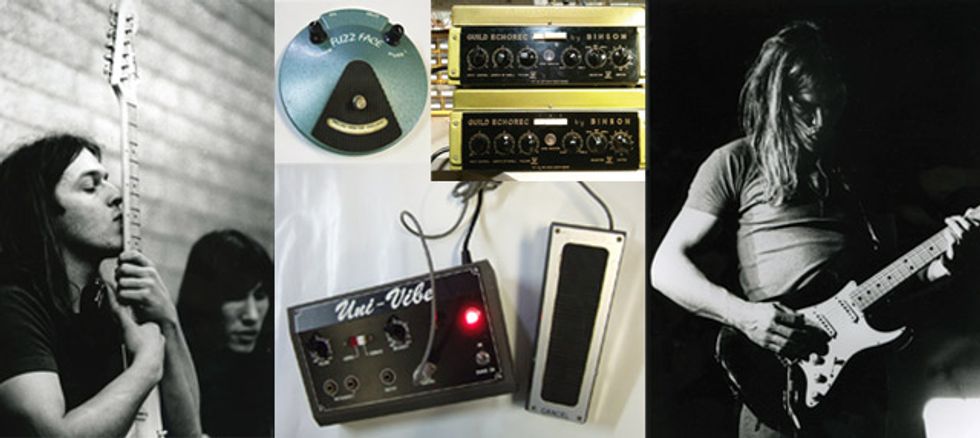

Gilmour's Gear

Guitarist David Gilmour used a

small arsenal of gear for the Dark

Side of the Moon sessions. Given

his penchant for changing his

rig—and the fact that the sessions

were scheduled around live gigs

and stretched over the course of

a year—it’s difficult to pin down

an exhaustive list of his Dark Side

setup. However, the following pieces

of gear are generally believed to

be the main tools for the sessions.

Guitars

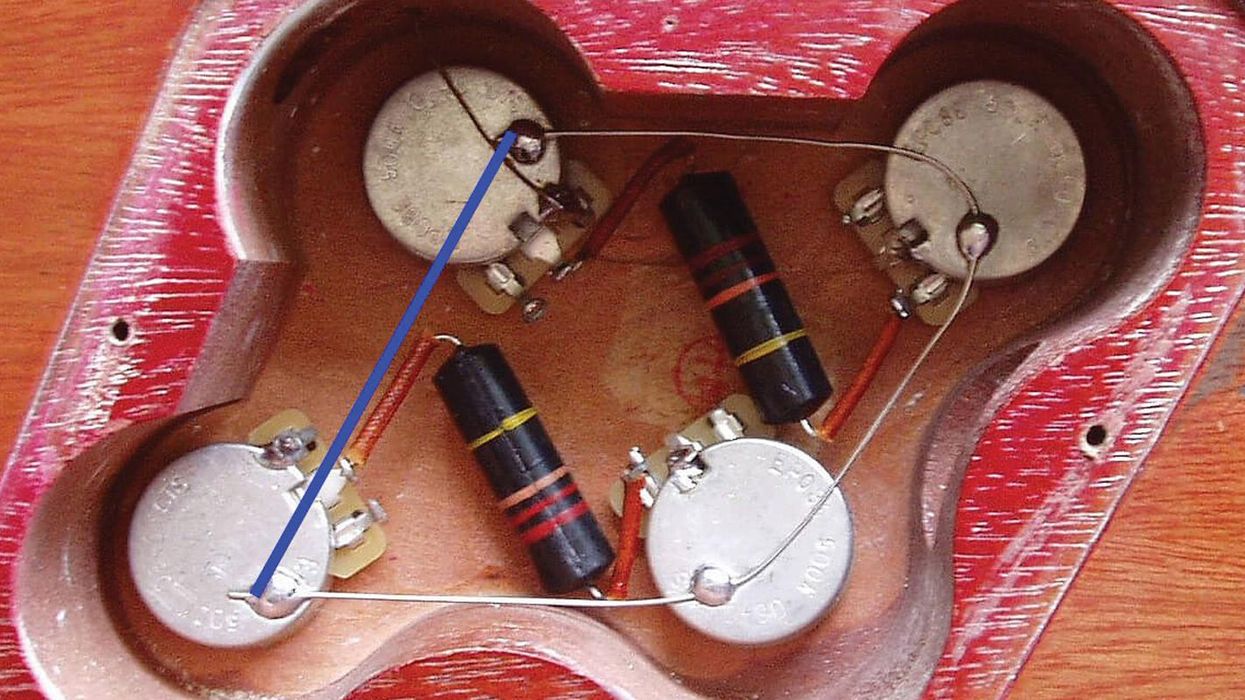

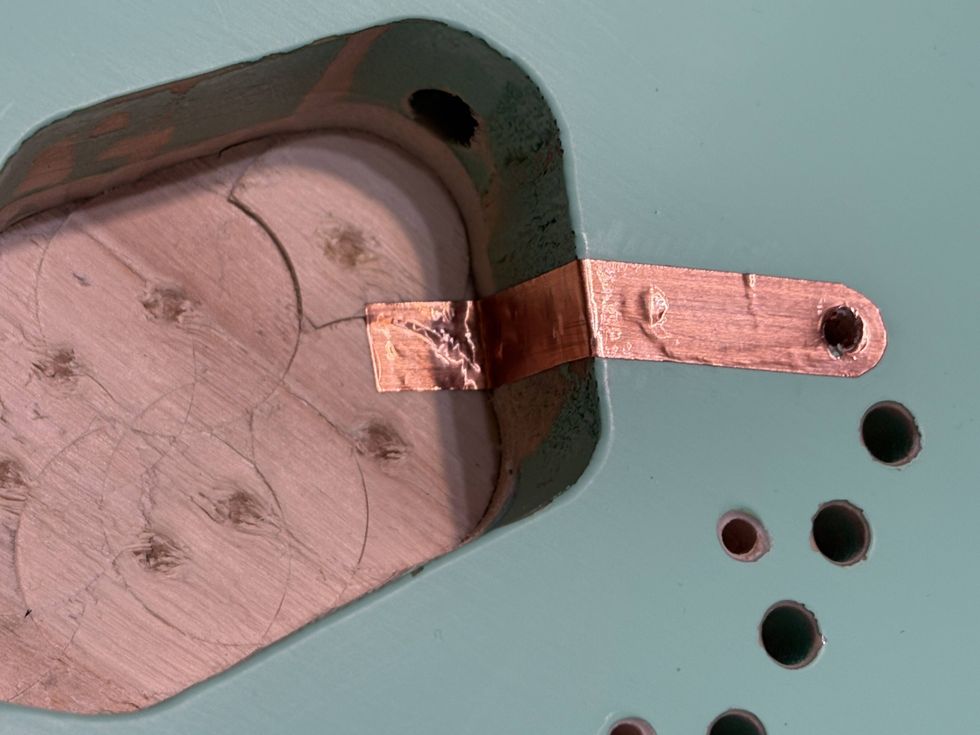

Gilmour’s famous black Fender Strat was his main axe during the Dark Side of the Moon

sessions. At the time of the recording, the oft-modified 1969 Fender Strat would have had

a ’63 neck with a rosewood fingerboard, stock single-coils, and an extra mini switch for

extra pickup combinations. In early ’73, a Gibson PAF humbucker was installed between

the bridge and middle pickups, but it is doubtful that pickup is heard on the album.

Gilmour also played a Fender 1000 pedal-steel guitar tuned in G6 (D–G–D–G–B–E, low to high). He also used a custom guitar built in 1970 by Canadian luthier Bill Lewis for parts of the “Money” solo. It had a mahogany body, ebony fretboard, 24 frets, and custom humbuckers, and it may have been used for other tracks, as well.

Amps

During the Dark Side period, Gilmour used Hiwatt DR103 100-watt heads through 4x12

cabinets. Alan Parsons recalls the cabinets being Hiwatts, while some sources (such as

Gilmourish.com) suggest they may have been WEM cabs. The latter source also suggests

that a Fender Twin combo was used on Dark Side, though Parsons does not recall that amp

being used. A rotary-speaker cabinet—either a Leslie or a Maestro Rover—was also used.

Effects

Gilmour is famous for his masterful use of effects,

both live and in the studio. Among those used

for Dark Side were a Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face, a

Binson Echorec II, a Colorsound Power Boost, a

Univox Uni-Vibe, a Kepex tremolo, and an EMS

Synthi HiFli.

Parsons' Go-To Mics

The Neumann U47, U 67, and U 87 microphones mentioned by Alan Parsons in this

interview have probably been used to record more hit records in more styles of music

than just about any other microphone models. They’re quite expensive—especially

vintage U 47s and U 67s—as are newer reproductions like those from Telefunken and

Bock Audio. However, below we’ve also listed some quality alternatives that will impart

much of their magic at a pretty reasonable price.

Neumann U 47

Manufactured from 1949 to 1965, the U 47 was a large-diaphragm

tube condenser microphone with a switchable polar pattern.

It is outstandingly versatile and excels on almost all sources,

including vocals and guitars. It has a clean sound with good presence

and nice top-end warmth. The Beatles’ producer, George

Martin, has stated that the U 47 is his favorite microphone.

In 1969, the U 47 FET—a very different microphone with solid-state electronics—was released. Many engineers prefer the FET version for recording kick drums and upright bass.

Neumann U 67

In the early ’60s, the U 67 was introduced to address some

complaints about the U 47—some engineers felt the U 47 could

be harsh and bass-heavy when used for close-up vocal recording,

which was becoming popular at the time. The U 67 is still

a large-diaphragm tube condenser, but it adds a bass roll-off

switch and has a slightly reduced upper midrange. It is also very

versatile, with a large diaphragm, switchable polar patterns, and

a tube-based condenser design. The U 67 became the studiostandard

workhorse for many engineers and producers.

Neumann U 87

The Neumann U 87 is among the most widely used mics in the

professional studio market. It’s a solid-state condenser with a

large diaphragm and switchable polar patterns. Many engineers

rely on it for vocals, but it has been used for almost all applications,

including orchestra, drums (Bruce Swedien of Count

Basie, Duke Ellington, and Michael Jackson fame swears by it

for toms), electric guitar, and more.

Large-diaphragm tube condenser alternatives: Mojave Audio MA-200 ($1,095 street), Rode K2 ($699 street), SE Electronics Z5600a ($849 street), Avantone Audio CV-12 ($499 street), or Studio Projects T3 ($599 street)

Large-diaphragm solid-state condenser alternatives: Mojave Audio MA-201 FET ($695 street), Audio-Technica AT2035 ($149 street), Rode NT1000 ($329 street), Blue Bluebird ($299 street), AKG Perception 220 ($179 street)

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

The Allparts team at their Houston warehouse, with Dean Herman in the front row, second from right.Photo by Enrique Rodriguez

The Allparts team at their Houston warehouse, with Dean Herman in the front row, second from right.Photo by Enrique Rodriguez