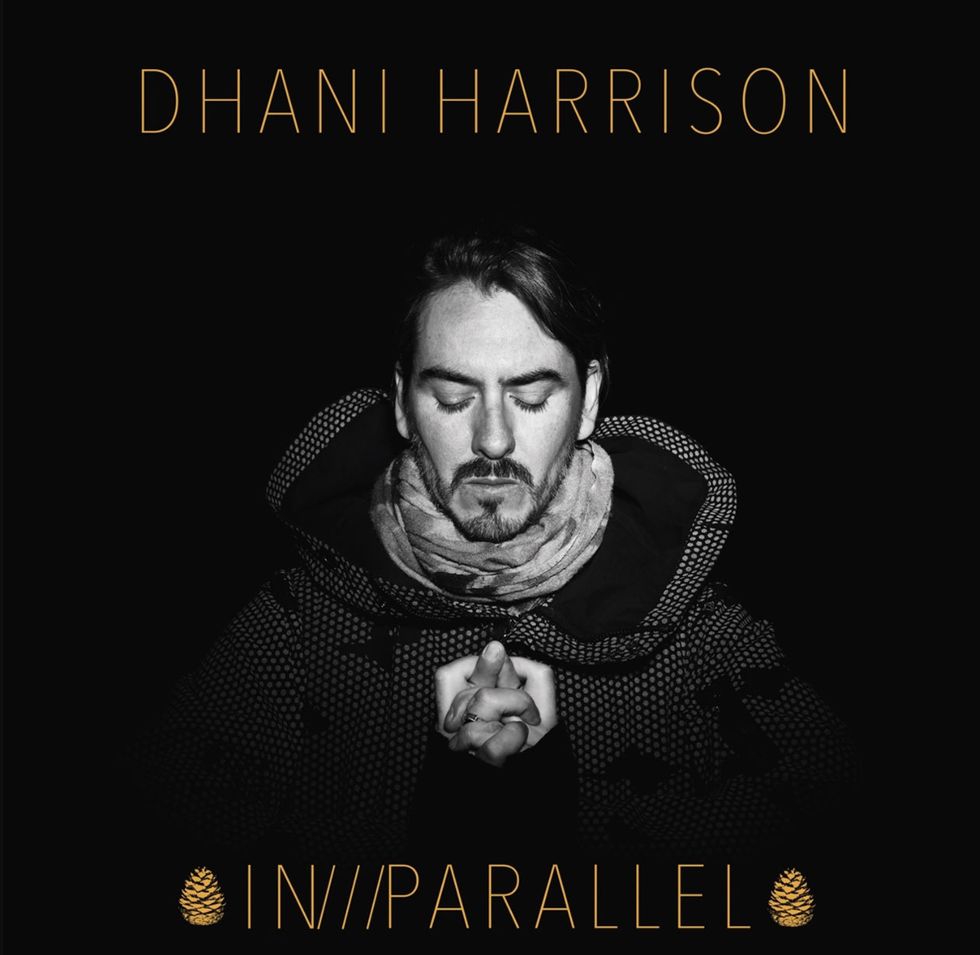

Dhani Harrison has recorded with Bob Dylan and Wu-Tang Clan, and is in the trio Fistful of Mercy with Ben Harper. He has created multiple film and TV scores. He's produced live concert albums and accompanying documentary DVDs—most notably 2016's George Fest: A Night to Celebrate the Music of George Harrison. He shared the stage with Prince (and Tom Petty, and Jeff Lynne, and Steve Winwood) during one of the Purple One's most iconic guitar performances: the 2004 tribute to his dad at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He also graduated from the prestigious Brown University with a degree in industrial design. And he's even been deeply involved with video game design for the popular Rock Band franchise. But right now, Harrison is focusing on the release of his long-awaited solo debut, In Parallel, an album that connects his musical history with his wide-eyed anticipation of his musical future.

From the day he was born, Harrison has been surrounded by a world of exceptional music. The house he was raised in was a bastion for iconic songwriting and songwriters, and through his father's work and extremely close relationships with such legendary artists as Petty and Lynne, Harrison received a stellar education in timeless musical craftsmanship.

“My dad turned our whole house into a studio. So, it's like you start as a tea boy, then you become a tape-op, then you become an engineer, and then you become the composer or the artist, I guess," Harrison explains nonchalantly.

Today, like his father before him, Harrison is the insatiable composer. He has written and recorded albums with his bands Thenewno2 and Fistful of Mercy. He and Grammy-winning musician Paul Hicks, a regular collaborator, have scored 2013's Beautiful Creatures and the TV series The Divide, as well as the 2016 Ryan David film, Seattle Road. Scoring Seattle Road turned out to be a serendipitous experience. “The director really just let us go to town on that one," says Harrison. “I wanted to take that further, so the sound of this record is quite similar to the sound of the stuff that I did on Seattle Road."

In Parallel paints film-like scenes while wrapping them in an accessible frame inspired by the great songs Harrison grew up around. As soon as the opening track, “Never Know," hits your ears, the similarities to a breathtaking film score are apparent. Pulsating ambiance melds with expertly layered Middle Eastern instrumentation, creating a sonic environment more than a typical song arrangement.

That spacious experience continues throughout In Parallel, leading one to ask, “Why am I reading about this in a guitar magazine?" As Harrison explains, even in an album filled with mind-twisting sonics, his guitars are never far away. “A lot of what you would think would be synth programming is, in fact, just guitar parts that are really processed." And so, like his father, Dhani Harrison is also a master of using the guitar to conjure gorgeous musicality, without resorting to the expected.

In our conversation, Harrison gave Premier Guitar readers a peek behind his creative curtain. He showed pride in being the son of a Beatle. He explained what it is to consider Tom Petty family. He dug into what drives him to conjure experimental guitar tones. He waxed about how his metal-at-heart band for In Parallel keeps him in touch with the rocker inside. And, most important, Harrison illustrated how he translated all of this into his debut solo album.

Being the son of a Beatle, your musical upbringing was unique. But what was it that initially attracted you to music?

I grew up in the studio. I always played music since I was a kid: piano, guitar, drums. And I sang a lot too. So I got my 10,000 hours early. Sometimes I'd come home from school and walk right into the middle of a tubular bells recording, and I'd be like, “Oops, I was just going in the kitchen." I'm pretty sure I tried everything possible to not do music. But I knew I was going to come back to it at some point.

What led you to film scoring and media production?

It's just the family business, really. I've always done design work. When it comes to my dad's catalogue, I've always helped him with artwork. Then, obviously, after he passed away, I finished Brainwashed as a producer, kind of taking his place as the artist. Jeff [Lynne] and I were co-producing.

TIDBIT: No guitar amps were used in recording In Parallel. Instead, Harrison exclusively relied on amp plug-ins from the likes of Native Instruments and Universal Audio.

He needed someone to make the decisions that we knew were going to have to be made. And I studied industrial design at Brown University. It comes in handy, especially for all the packaging and all the custom stuff I've been doing. It was just trying to maintain the most amount of control over the quality of the products that we're releasing.

What inspired you to release a solo album now?

I always write by myself. I very rarely write with people, even though I collaborate with people. So I had gone really far down the rabbit hole of making this record before anyone else came in. I tried to get Paul Hicks to collaborate with me, but he was like, “Wow, this is already a fully formed band. This needs to be what it is." And I had Jon Bates from Big Black Delta say the same thing. He was like, “I don't want to change this. I hope you put it out under your name." And I was like, “Okay. Maybe that's what I should do." And the further along I went with it, the more I realized that was the answer.

The harmonies and the chorus on “All About Waiting" and “Admiral of Upside Down" definitely bring the Beatles to mind. Is that intentional or simply a product of who you are?

Purely a product of who I am. I love stacking vocals; I love harmonies. I really wanted to have great harmonies in this record. After doing Fistful of Mercy and having such great singers in the band with me—Ben Harper and Joseph Arthur—I was missing out on the vocals. I really wanted great singers on this record. Jonathan Bates—I came in to sing with him on his Big Black Delta record. So after we'd done that, I was like, “Jon, definitely!"

Female vocalists also play a prominent role throughout the album.

I'm trying to write a story about what's happening right now. What's happening to man and woman alike, and female perspective is so important in the story. They've got to be strong characters like Camila Grey [featured on “All About Waiting"] and Mereki [“London Water," “Poseidon (Keep Me Safe)"]. Cami Grey was singing on [Bates'] record, so she was definitely in. And then the last person to come in was Mereki. She's just got such an interesting sound and she's such a great songwriter. I was playing guitar in her band, so that was a no-brainer. She really nailed it the first day, and it was like, “Oh, okay. We need to make a whole other record now." [Laughs.] It was too quick. So, it's me and Jon with the male characters and Cami and Mereki with the female characters. Everyone knew each other so well, and it was just really natural.

Harrison plays one of his custom Fender Stratocasters onstage. His personal Strats start with the Eric Clapton signature model as a template, but feature a humbucker in the bridge position. Photo by Lindsey Best

You had a few other notable musicians on the album, like Stephen Perkins from Jane's Addiction.

Yes. Stephen Perkins came in to play some drums. So did my old drummer Frank Zummo, who's now in Sum 41. Also, Davide [Rossi] was great, because I'd composed a lot of the strings myself. And then he came in and did a bit of ad libbing, orchestrated it, and then played the orchestra. He's a one-man orchestra! When this record came up, he said, “I want to be on this." Even though it was already mostly done, the freestyle violin that he brought, the Indian sounding stuff, was so great.

Like the violin, the guitars on the album have a very different texture. What did you use to get those super-processed sounds in the studio?

I didn't really use any amplifiers in the making of this record. I work in the box, because there are such great amp simulators. I really get into processing guitar sounds backwards, but playing them forward while having the delay set to 100 percent backwards. A lot of those guitar solos were done like that. There's definitely one of those on “Úlfur Resurrection." And “London Water" definitely has that backward stuff.

What guitar amp software do you use?

I have always liked Native Instruments. But I use the Arturia and all the Universal Audio simulators, and stuff like that. The sounds that I use on the record are so dirty and distorted and bit-crushed anyway that it doesn't really help playing them through an amplifier. It's just that extra step that you don't need. If I was doing a band album, and I wanted a really warm, nice tone, then obviously I'd go in and mic everything. But it's a very cut-up tone. So I just use my pedalboard into the box.

“Admiral of Upside Down" is the most guitar-driven track on the album. Did you also record it straight into the box?

Straight into the box. It's an old 1940s tenor Gibson. It's a 4-string with a P-94. That's all you need, really. That one pickup sounds so good, and that was a very clean sound. We had a little bit of reverb on it and a little bit of tremolo. And then the stuff at the end: That's all a lot of ZVEX pedals that I use. I love the ZVEX pedals. And I still love using a Blues Driver—I've got a modded one.

Which ZVEX pedals are you using?

I like the gated distortion, the Box of Metal … I don't want to give them all away, but that one is definitely good. When the gate kicks in, it really cuts everything off in a bit-crush kind of way. The sound of that signal dying can cause really great happy accidents when it's going through other delays and other things.

Was there a selection of guitars that you gravitated toward for the album?

Definitely used a lot of that tenor guitar, which I'm really in love with. I can't remember the model number. But I build a lot of stuff with Fender to be very custom for me. I have my own model of Stratocaster, which I've been working on for about 10 years now. I based it on the Eric Clapton model, because I always loved how he had that mid-boost and that extra gain from the Lace Sensor pickups. But I never really liked the bridge pickup on the Lace Sensors. So I put a dual-coil humbucker in that one. It's just a lot of tinkering.

Most of my stuff is built by Paul Waller, the [Fender Custom Shop] master builder. Paul and I have been working on lots of George Harrison guitars. We did the rosewood Telecaster. The Custom Shop sent me the mass release one the other day, which just sold out. And he's building me another Strat with a Floyd Rose in it. I've owned a million Strats, and I can't really play the normal ones anymore. They just sound a bit clunky to me.

Guitars

1940s Gibson ETG-150 tenor guitar

Fender Custom Shop Stratocaster by Paul Waller

Custom Charvel S-type by Paul Waller

Amps

Fender '65 Twin Reverb reissue (live)

Native Instruments Guitar Rig

Universal Audio plug-ins

Effects

ZVEX Box of Metal

Boss-BD-2 Blues Driver (modded)

DigiTech Whammy

Electro-Harmonix Memory Boy analog delay

Universal Audio plug-ins

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Hybrid Slinky (.009–.046)

Dunlop Tortex (.73 mm)

Watching you play a live version of “Summertime Police" on YouTube, it seems like you lean more on the organic sound of the guitar live.

It's got to be bold. It's got to be rude. You know what I mean? On the record, there's Jon Bates playing a custom Charvel that was also built by Paul Waller. And Jon was saying, “Wouldn't it be great to bring back some shredding on this record?" And it made the cut. And then I was like, “Oh, great. Now, I've got to get a Charvel or something with a locking nut, because I'm going to be playing all these songs with these huge bends in them." My bass player Blas [Perez], my guitar player Noah [Harmon], and my keyboard player Josh [Giroux], and Jon Bates as well—they're all classically trained, incredible shred guitarists. Way better than me. But the band is very metal. All of these guys play with such a metal-y kind of vibe. I feel it sounds good to be a bit heavier live.

Do you still use amp sims live?

Oh, no. I use my newer blackface Twin Reverb. I always use the Fender Twin, because it's loud as fuck. And I got my pedalboard down to a fine art now. It's like my 50th pedalboard that I've built.

What pedals made it onto the live board?

I really love the DigiTech Whammy. I'm not really that into the new models of them, because they break really easily. I've broken probably 20 of them. But it's one of those pedals that's just so good. I use a Memory Boy, because it's got a great tape delay feel to it. Again, my favorite distortion is that Box of Metal. That's mostly what I'm using.

Rocking out onstage with Big Black Delta, Harrison plays one of his custom Strats. “I've owned a million Strats, and I can't really play the normal ones anymore," he says. “They just sound a bit clunky to me." Photo by Debi Del Grande

Recently, the music world lost Tom Petty. You and your father had a close personal relationship with him. What did his music mean to you?

Good times. Like, ever since I first came across Full Moon Fever. And Jeff and my dad were so close with him, even before Traveling Wilburys was made. I remember listening to the making of that stuff and getting advance copies sent to my dad from Tom. He'd be like, “You want to hear Tom's new stuff?" And it would be the first time anyone's heard “Free Fallin'"—you know what I mean? And then again, later when they did the Wilburys' second album, I was actually living in the studio where the Wilburys were recording. So I was like a Wilbury mascot.

You're credited on that album.

I sang and played on the album. I was Nelson Wilbury on the first record and I was Ayrton Wilbury on the second record. My dad had chosen Nelson Wilbury after Nelson Piquet, the racing driver. And I had chosen Ayrton Wilbury after Ayrton Senna, the Brazilian racing world champion. So that was kind of a nod to my dad as well.

But Tommy is just, like, the loveliest guy in the entire world. It's like what Marc Maron said: “The only two things that Americans can agree they like these days are burritos and Tom Petty." We all like burritos and we all like Tom Petty.

I mean, him and Jeff have been the nearest things I've had to a dad since I lost my dad. I've just spent a week with the Heartbreakers. I mean, even Steve Ferrone [Heartbreakers drummer] came down to support me on Jimmy Kimmel the other night. And Jeff came to my album release party, and sat and listened to my whole album with Annie Lennox. It's just the really supportive and wonderful people in my life.

From 2002's Concert for George to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction performances, I've noticed that your father's music has a way of bringing musicians together. What is it about your father's legacy that has created this impact?

I think he just stood for good things. He really stood for being a conscious person and he loved his friends. And I think people feel good when they play his music. He just hit a frequency that seems to touch people in their hearts.

I have to say, you're right though. Whenever there's anything to do with my dad, we don't have to call anyone to say, “Will you come play?" When we did George Fest, we had a slot open up on the Conan O'Brien show. And within a minute, we got Paul Simon. He came and did “Here Comes the Sun" and it was like the whole theater was in tears.

I could see how the legacy of your father and the Beatles could be a burden for some. But it sounds like you're able to use this as an inspiration and a source of light.

Totally. It's empowering. Their music is really a call to wake up. Listen to things like “Baby, You're a Rich Man." Listen to the lyrics of that song: Now that you know who you are, what do you want to be? There's messages in those songs. Paul and John and my dad—those guys covered everything. And so I find it very empowering.

With In Parallel, do you feel like you've found your voice as a solo artist, or is this one step in the evolution of Dhani Harrison's music?

If this is the first Dhani Harrison movie, this would be my Lethal Weapon 1, you know what I mean? I was always more of a fan of Lethal Weapon 2. I look forward to making that soundtrack to that movie that's never been made. But I have to go and live the experiences. So I hope to do a bit of traveling and really take my perspective further out. And I really want to study perception and work out what it means to experience things and how to best document them in music. So I think this really is a starting point.

His dad's fourth solo album was called Extra Texture. Here, in this excerpt from a recent performance of “Summertime Police" at Brooklyn's Knitting Factory, Dhani Harrison puts that into practice with his custom Charvel guitar, built by Fender master builder Paul Waller.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)