Kenny Greenberg has been Nashville’s secret weapon for decades. He’s the guitarist many insiders credit with giving the Nashville sound the rock ’n’ roll edge that’s become de rigueur for big country records since the ’90s. It’s the sound that, in many ways, delivered country music from its roots to sporting events.

Greenberg’s list of album credits as a session guitarist, producer, and songwriter is as diverse as it is prolific and includes everything from working on Etta James, Willie Nelson, and Sheryl Crow records to shaping hits for mega-selling contemporary country artists Toby Keith, Faith Hill, Brooks & Dunn, and Kenny Chesney (who Greenberg also tours with on lead guitar). Greenberg’s even been kicked in the leg by Jeff Beck! (More on that later.) So, while you might not necessarily know Kenny Greenberg by name, it’s safe to say you’ve heard his guitar playing.

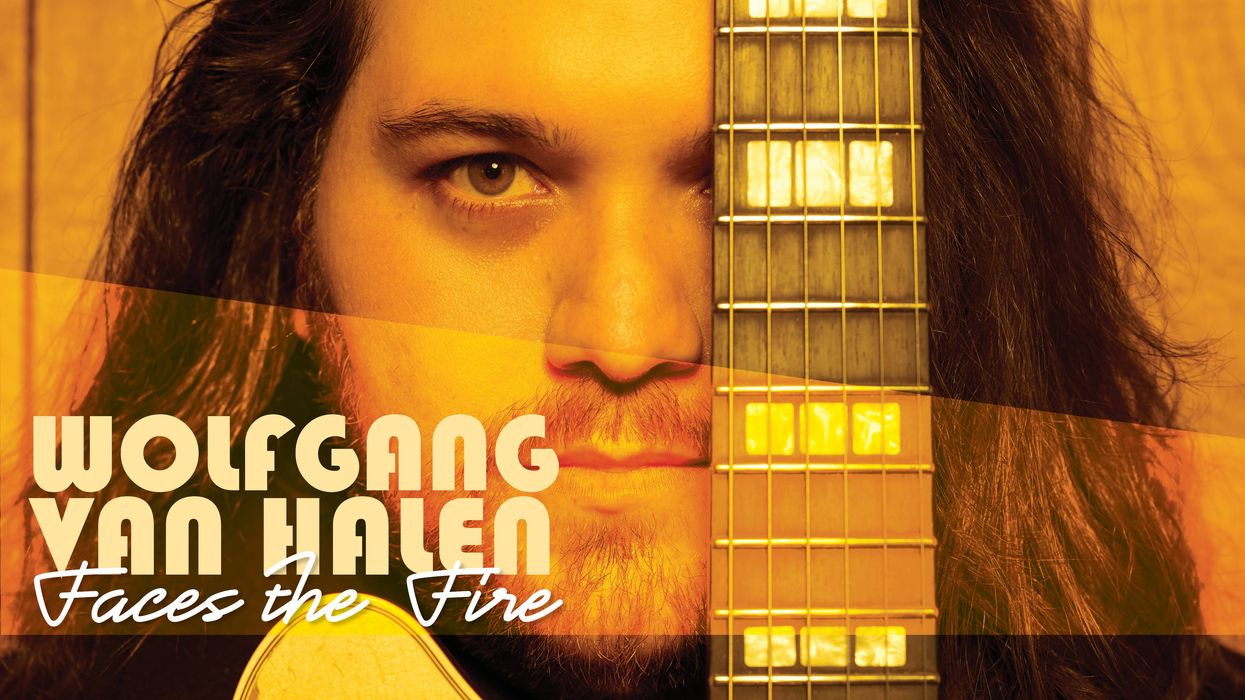

Since moving to Nashville in his teens, Greenberg’s kept his dance card remarkably full working on records for other artists. However, with the release of his debut solo album Blues For Arash, the decorated session veteran has finally made a statement all his own—even if he didn’t necessarily intend to.

Blues For Arash is a collection of songs that were intended for the soundtrack of a movie written and directed by Welsh-Iranian filmmaker Arash Amel. The film tells the tale of a West African musician who becomes enamored with the blues and finds himself on an odyssey through the Southern U.S. Unfortunately, the movie never quite got its production together and remains in a state of funding limbo, but Greenberg found an unexpectedly happy space within the project to create music that he feels represents his truest self as a player, and he quickly realized that these songs had the makings of a solo album.

Blues for Arash

TIDBIT: Kenny Greenberg recorded Blues For Arash at his own pace in his Nashville home studio, originally intending to make a soundtrack for a film by Emmy-winner Arash Amel.

Greenberg explains: “All my guitar player friends said, ‘This isn’t what we were expecting!’ To me, it’s really the kind of guitar music I would make for myself. I’m not really a shredder, anyway. I do a different thing.”

Blues For Arash is a remarkably musical affair that shirks the fretboard histrionics that often characterize instrumental guitar albums by players with similar resumes. The album fuses African influences, exotic percussion loops, and field recordings with Greenberg’s unique take on blues guitar in a way that’s genuinely refreshing and as cinematic as one might expect of songs written to accompany a movie. The track “Nairobi, Mississippi” acts as the album’s thesis statement and is a one-chord blues that features Greenberg’s Mississippi-hill-country-blues-informed bottleneck guitar dancing with West African musician Juldeh Camara’s brilliant nyanyero (a single-stringed fiddle) over an energetic African percussion loop.

From the ultra-lyrical slide playing on the opening track, “The Citadel,” to the fiery, fuzzed-out lead work on “Star Ngoni,” all of Greenberg’s guitar on the album is rooted in the blues. The guitarist and songwriter confesses that despite the diversity of his credits, the blues has always been his home base: “Everything I do comes out of a weird way of playing the blues. So, we had the idea to fuse African music with the blues and I started researching cool beats and stuff that I could play blues guitar over, and I would come down to my studio with samples or loops, or I’d loop actual field recordings, and I would just play over them.”

“We had the idea to fuse African music with the blues and I started researching cool beats and stuff that I could play blues guitar over.”

Greenberg played most of the instruments on the album and edited many of its loops and percussion beds, but he did have some important collaborators, including multi-instrumentalist Justin Adams, who plays in Robert Plant’s band the Sensational Space Shifters and has produced Tuareg/desert-blues greats like Tinariwen. Adams provided some of the raw material that Greenberg would throw his blues playing on top of, and the two would share ideas through email. “Justin was a good guy to call for an opinion on that African/blues fusion thing,” says Greenberg, “and he’s a very cool and knowledgeable guy about world music in general. I look forward to doing more with him.”

Greenberg’s key collaborator on the record is Wally Wilson, who he describes as a mentor and who he met while co-producing the live-performance TV show Skyville Live for CMT. “I met Arash through Wally, and we came up with this idea of the soundtrack being blues guitar, but with an African influence,” Greenberg says. “Wally was very important in this process and co-produced the record.” Wilson, who has never fancied himself a singer, even ended up providing the narrative-style vocals on “Memphis Style” and “Ain’t No Way.”

“Wally and I both love Howlin’ Wolf and all the hill country blues. I had a cheap handheld mic in my room, and I was like, ‘Put the vocal down so we have the general concept, and then we’ll get a killer soul singer to come in and re-do these,’ but it just had such a character to it! It has this lo-fi, non-professional vibe that just sounded right. It took Wally a long time to get on board with us using his vocals, but I’m glad he did!”

Kenny Greenberg’s Gear

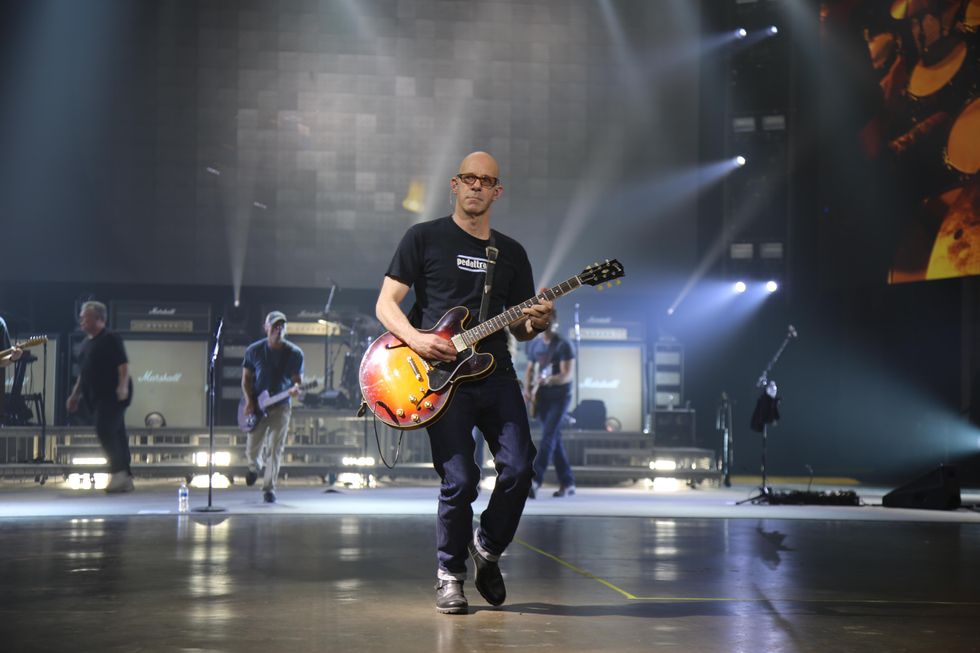

This Gibson Custom Shop ES-335 is a favorite for Greenberg, who, after nearly 30 years in Nashville, is as comfortable onstage in stadiums and arenas as he is in clubs and studios.

Guitars

- Vintage Gretsch 6118 Double Anniversary

- 1962 Gibson SG Special with mini-humbuckers

- Russ Pahl S-style

- DiPinto Galaxie

- Harmony Sovereign

- Dobro-made National wood-bodied resonator

- 1952 Les Paul goldtop

- Gibson Custom Shop ES-335

- Jerry Jones Baritone

- Jerry Jones 12-string

- Fender Telecaster with Glaser B-Bender

- Fender Jazzmaster

- Novo Serus J

- PRS Silver Sky

- PRS DGT

- GFI Pedal Steel

Amps

- Fender Pro Junior

- 1958 Fender tweed Deluxe

- Hime Amplification The Rockford

- Vox AC30

- Matchless HC-30

- Magnatone Varsity

- Marshall 20-watt

- ’50s wide-panel, low-power tweed Twin

Effects

- Mythos High Road Fuzz

- J. Rockett The Dude

- Karma Pedal MTN-10

- J. Rockett Archer

- Universal Audio Ox Box

- Boss DD-200 delay

- Walrus Audio D1 High Fidelity Delay

- Walrus Audio Slö reverb

- Boss GE-7 Equalizer modded by XAct Tone Solutions (XTS)

- Line 6 M9

- JHS Colour Box

- JHS 3 Series OD

- Keeley Dark Side Workstation

- Pedalboard by XTS

Strings, Picks & Slide

- D’Addario NYXL (.010–.046 for standard electrics, and .013–.068 for slide)

- Ceramic and glass D’Addario slides

- Dunlop Tortex Teardrop .88 mm for electrics

- Fender Mediums for acoustics

Beyond rolling with a scratch vocal for the final cuts, Blues For Arash has a wonderfully playful quality that Greenberg says was “totally different” from what he typically does in the session world. “I was like, ‘I don’t give a shit! I can play anything I want to play. I’m going to make myself happy with this!’ The thing about the pandemic in Nashville is so many artists live here, and they were all off tour, obviously, and wanted to record. They wanted to put masks on and go in the studio and be careful because they couldn’t go on the road. I actually worked my way through the pandemic—and I’m grateful for that—but when I had a day off, I’d come down to my home studio and work on these songs. It’s what I really wanted to do with my own time.”

Despite the massive arsenal of guitars, amps, and effects Greenberg has at his disposal as a top-tier session player (who PG once covered with a truly comprehensive Rig Rundown), he kept it to a few choice instruments and amps to craft the fabulously organic tones on Blues For Arash. The main guitars included his trusty vintage, stripped-down “players-style” Gretsch 6118 Double Anniversary and a custom S-style build by famed Nashville steel guitarist Russ Pahl. For the album’s killer electric slide playing, Greenberg used a 1962 Gibson SG that he literally found in a garbage can and loaded with vintage mini-humbuckers, and a DiPinto Galaxie. A vintage Harmony Sovereign and a wood-bodied Dobro resonator guitar handled the acoustic slide work.

“Richard [Bennett] was the first guy that I saw use a Gretsch and it sounded like Duane Eddy, but modern. It had a real bell-like-but-not-bright sound. I immediately thought, ‘I got to get in on some of that!’”

While Gretsch guitars have become a popular choice for pros in Nashville these days, that wasn’t always the case. Greenberg caught the Gretsch bug from session guitarist Richard Bennett—another unbelievably prolific and important player/producer that you may know as Mark Knopfler’s longtime right-hand man, who has influenced Greenberg’s path tremendously.

“Richard Bennett played on my wife’s [singer-songwriter Ashley Cleveland] first record and brought me in because I played live with her. Richard would hire me, and I’d be the second guitar player on sessions with him a lot, and watching him was like, ‘Motherfucker, that is the way you do it!’ Richard’s Gretsch playing and acoustic playing were huge, huge influences on me. Richard was the first guy that I saw use a Gretsch, and it sounded like Duane Eddy but modern. It had a real bell-like-but-not-bright sound. I immediately thought, ‘I got to get in on some of that!’ Gretsches do a unique thing and I also really like them for distorted solos. Mine is not that bright of a guitar and it has this great upper midrange kind of twang that’s somehow not a twang. I’ve got a couple of different ones, but that old Double Anniversary I use a lot. It was the first Gretsch I bought, and it’s really good. I went down to Gruhn’s and they had it on the wall for $600. It had the original pickups, but the finish had been taken off and the headstock had been repaired. So, it’s a great example of a ‘player’s vintage instrument,’ where it’s got the old wood and the sound, but it’s not $5,000. I just fell in love with playing it. Also, the Bigsby bar is huge for me.”

Rig Rundown - Kenny Greenberg

For amps, Greenberg looked exclusively to the Fender realm to conjure Blues For Arash’s lush tones. A ’90s Pro Junior mated to a 4x12 cab, a black-panel Deluxe Reverb-style amp made by Jeff Hime called the Rockford, and a ’58 tweed Deluxe all made important appearances. The tweed was even used to amplify and layer some of the acoustic tracks—a trick Greenberg picked up as a Neil Young fan. “Neil Young’s playing is right up there at the very tip-top for me, and his acoustic sounds are, too. There’s a record he made called Le Noise with Daniel Lanois, and I think those are some of the best acoustic guitar sounds ever. I’m never going to sound as raw as Neil sounds because when I’m playing on someone’s record, it’s a service for their music, so I don’t get to go completely crazy. But I’ve always been the guy that gets called when they want it a little rough around the edges. I aspire to play as raw as Neil plays and intend to have it be as emotional as that. I always feel like, when I’m in the room with all these other amazing guitar players, that my playing is a little craggier and looser. That used to really bother me, but now I really like it. I never really spent that much time trying to be what I’m not. I used to try to pull off some super-clean Brent Mason kind of things and they would go ‘No, no, we’ll call Brent when we want that. You do the thing that you do!’”

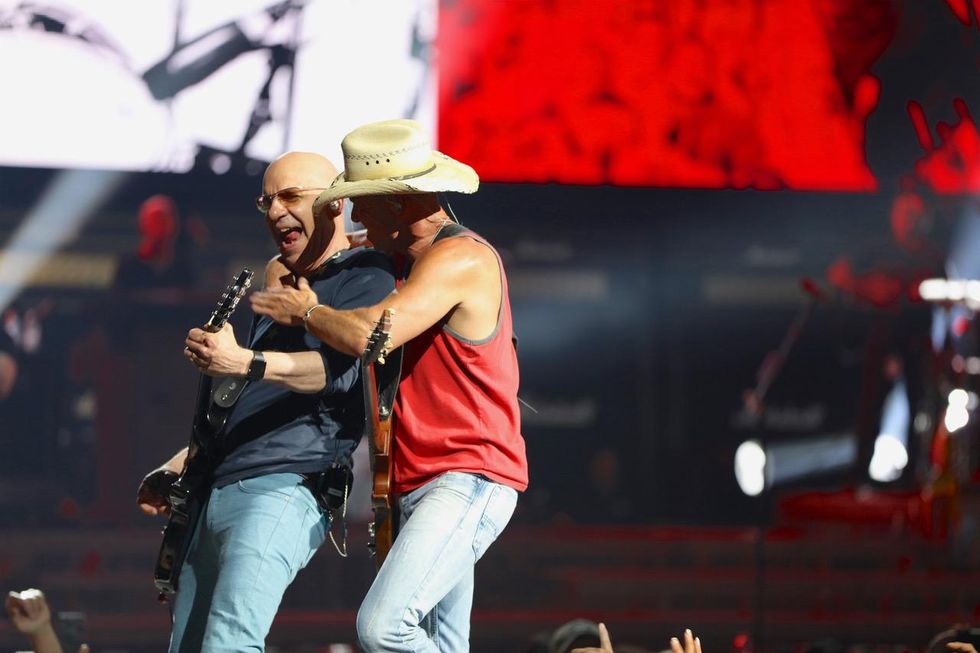

Among Greenberg’s numerous credits is his ongoing gig playing lead guitar for country star Kenny Chesney.

Photo by Jill Trunnell

If you sift through Greenberg’s album credits—which is a full day—it becomes apparent that many of the records he’s played on over the years telegraphed the rock-oriented direction popular country music ultimately took. However, Greenberg makes it clear that being “Nashville’s rock guy” was never intentional.

YouTube It

In a 2019 Skyville Live performance, Kenny Greenberg flexes his blues and rock chops on a Gibson ES-335 in a rendition of “Whipping Post” with guest Chris Stapleton.

That said, Greenberg’s still elated to be doing session and production work and proud of where he’s landed. With the release of his first bona fide solo record, one might expect him to be looking back, taking stock of the journey, and ruminating on his many, many years in the business of making hits. However, when asked what songs and contributions he’s proudest of, Greenberg stays in the present. “That’s a hard thing for me because the last thing I did is always my favorite thing. I’m so excited that I got to just do something. The great thing about recording is you play with all these great different people!”

When pressed again, Greenberg points to his work on Hayes Carll’s recent album, You Get It All. “My playing on that record feels like that’s who I am. There’s a blues solo on a song called ‘Different Boats’ that’s really where I’m at. And the song from my record ‘Star Ngoni’ is who I am as a player. If I’m going to open up and really play, that’s the way I play. And I would mention one other moment I’m really proud of: On my birthday one year, I did a version of Bob Dylan’s ‘Gotta Serve Somebody’ with Willie Nelson. We played our parts live and Willie was in there with Trigger [Nelson’s famous Martin acoustic] and that Baldwin amp he uses, and you could hear the radio station through the amp, and we sat there and played it together. That was huge. It was the best birthday a guy could have—playing a Dylan song, looking through the glass at Willie Nelson. I’m very, very aware of how fortunate I am to be doing this. I think about that a lot.”

Playing with Jeff Beck is a kick!

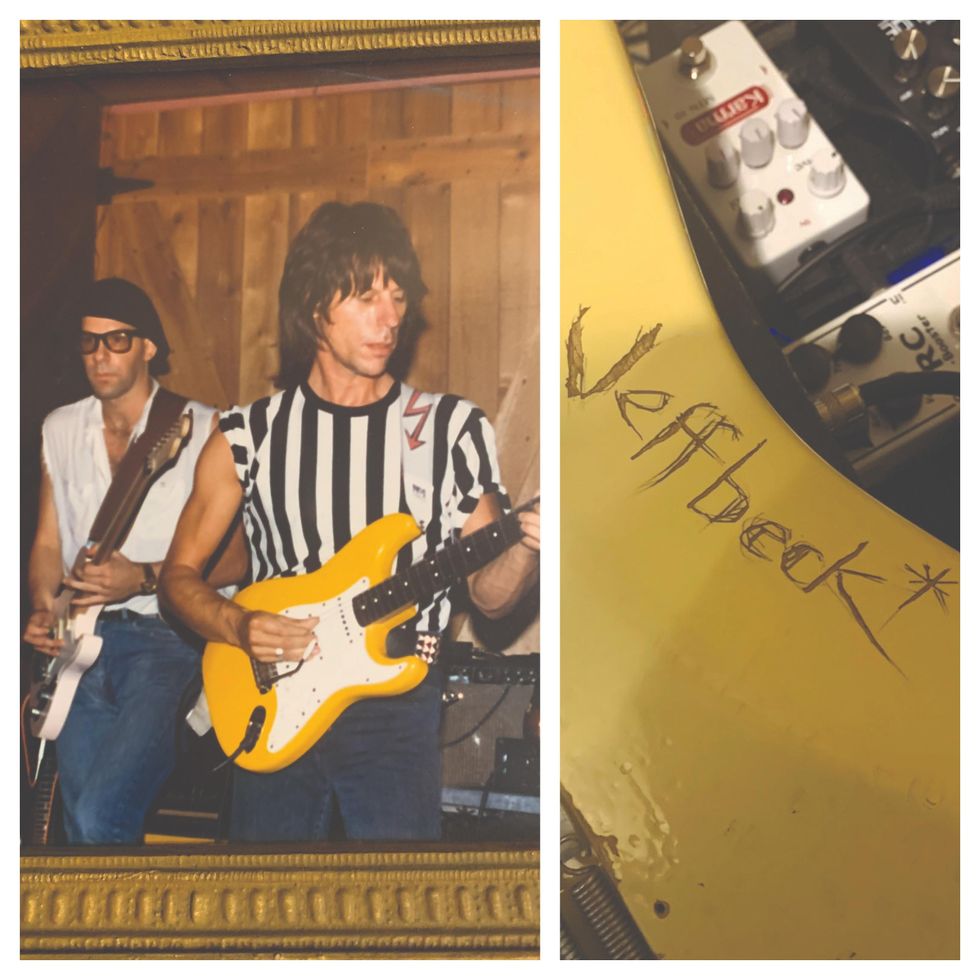

Greenberg and El Becko: On a gig with vocalist and harmonica player Jimmy Hall, Hall’s occasional boss Jeff Beck sat in, leaving Greenberg with an indelible memory.

There are quite a few parts on Blues For Arash that recall Jeff Beck’s lyrical, fluid playing at its best, particularly Kenny Greenberg’s vocal slide phrasing. It turns out Greenberg isn’t just a massive Jeff Beck fan. He’s had a remarkable run-in with the man himself.

“I’ve got a guitar that Jeff Beck carved his name into! Jeff came and sat in at a gig I was playing with Jimmy Hall, and he broke a string and played my guitar. Afterwards, he got a knife and ornately carved his name in the back of my Tele. How can you not be a fan? He’s the most vocal guitar player there is! My other little Jeff Beck story is from that same night—it’s the only time I’ve ever played with him—and we did ‘Rock My Plimsoul.’ We were playing that song, and he takes the solo. And, of course, it’s the way he plays now—improv where you just can’t fucking believe what he’s doing. Then he looks at me to take a solo, and that’s one of my favorite early Jeff Beck songs, and I actually know that solo note-for-note. So, I played his solo from the original and he looked at me, and he kicked me when I finished the solo! He reached out his leg and he kicked me, and I’m like, ‘Alright! Jeff Beck just kicked me! This is a watershed moment I’m having!’

“I remember standing right next to him, and, of course, I’m nervous. He’s like the greatest guitar player alive. He’s a savant and just looks down at the guitar and fingers and taps on it, and then he’ll use his thumb or his middle finger. It’s just like a kid screwing around. I just watched him, and I didn’t even know what he was doing, but it’s a beautiful, wonderful thing to watch.”

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.