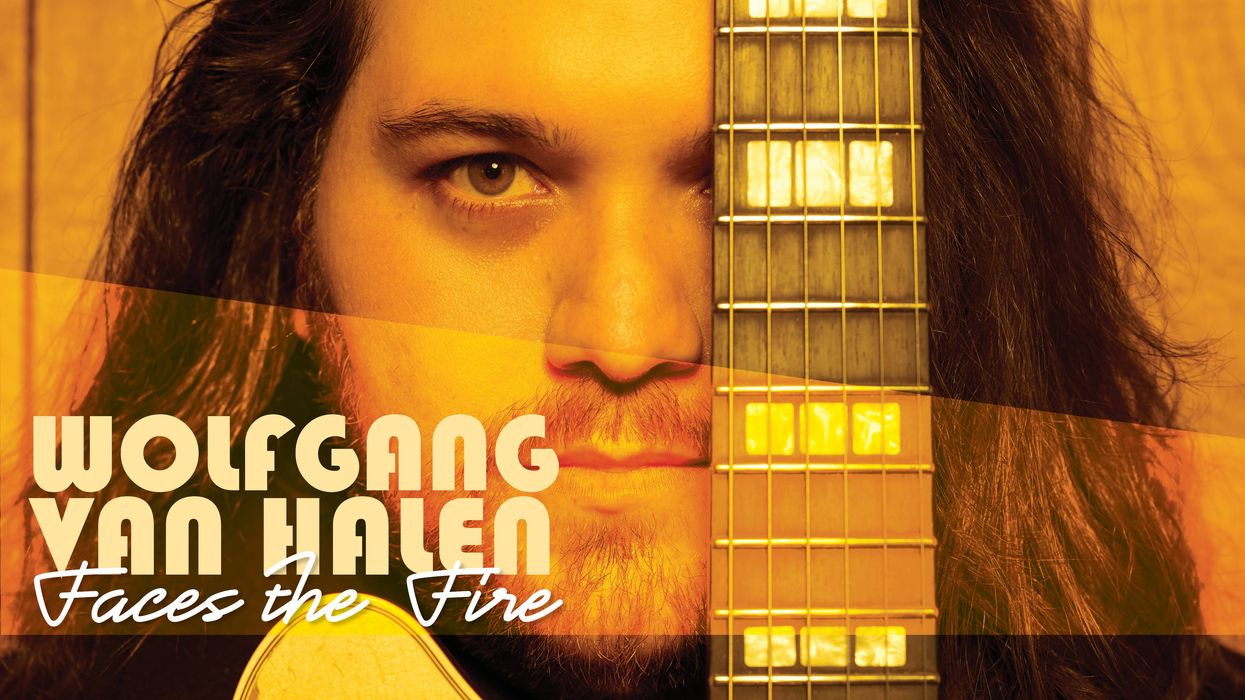

One of the core ingredients that is essential to any Bros. Landreth album is also the most dreaded: abject fear and panic. It doesn’t sprout up from any particular insecurity about the end result, but rather where to start. “We always say we’re going to write 30 tunes and pick our 10 favorites,” says Joey Landreth. “But we usually write 12 and pick 11.” At first, the fear was unsettling, but Joey and his bassist brother, David, have not only thrived under the self-imposed pressure but relished it. Factor in a world-changing pandemic, the experience of being new dads, and a soul-crushing session gone wrong, it’s amazing that Come Morning even saw the light of day.

Back in March of 2020 the band had finished two legs of touring behind ‘87, their tuneful return to form after a pair of solo albums from Joey and some time away from the band for David, who had just become a father for the first time. Joey had plans to tour behind his Lowell George tribute album. Naturally, all that went away. Tour dates were canceled, and bins of merch collected dust on the shelf. Once the duo came to terms with the uncertainty of their touring future, they immediately went to work on writing new tunes. But would it be for a solo record or another Bros. album?

The Bros. Landreth • Come Morning (Visualizer)

“I had this idea of making a solo record in my apartment,” remembers Joey. He lived in a 100-year-old building in Winnipeg where he converted the dining room into a home studio. After starting that project, mostly in isolation, with programmed drums, he played the songs for David and thought the material might better be suited from a Bros. album. “We asked ourselves what it would sound like if we merged my solo stuff with the Bros,” says Joey. “There weren’t any timelines, we weren’t career planning or writing with intent,” mentions David. “We were just making things because there was nothing else to do.”

The first two demos that they tracked were “Drive All Night” and “Corduroy.” On Come Morning, both songs feature sparse arrangements and touches of R&B influences, all mixed in with swirling sonics. “The demo for ‘Drive All Night’ was basically fully formed with programmed drums and weird stuff,” says Joey. “It was quite a departure for us.” Naturally, the next step was to start recording drums. The band found a window where travel was permitted and flew in a drummer from Edmonton to begin tracking the first half of the album. It soon became apparent that the result of the session wasn’t matching the Landreths’ vision. “When we didn’t get there, we were fucking gutted,” says David. “It was devastating. It almost killed us.” A few of the tunes were recorded at the wrong tempo, the bass lines didn’t sound like David, and it was the first Bros. album without drummer Ryan Voth. “You write these songs, you make a plan to record the best album you’ve ever made, you get through seven tracks, and you didn’t get it.” Heavy vibes.

“We’re always trying to put mics in stupid places.” — Joey Landreth

After making the tough decision to scrap the sessions, Joey and David sat down and made a dream list of drummers they would want on the record. The two names at the top of the list were Aaron Sterling and Matt Chamberlain, two studio veterans whose combined credits include David Bowie, John Mayer, Bruce Springsteen, Taylor Swift, and countless others. “We sent an email to both of them, and they both said yes,” says Joey. “Fuck, how do we choose between them?” According to the brothers, it simply came down to Aaron’s enthusiastic response. Once Sterling was in place, the band sent him a demo for “Stay,” a grooving, mid-tempo tune that features some inventive open-tuned rhythm parts. “The demo had programmed drums and we outlined what we wanted him to play,” says David. “When we got the tracks back, they were wickedly inspiring and took the song in a completely different direction.”

As the long-distance sessions progressed, Sterling meshed well into the creative process and even pushed the limits of what would typically be acceptable on a Bros. Landreth record. “I remember getting the Dropbox folder and seeing the files for bongos and was like, ‘Well, that’s a hard no on the bongos,’” laughs Joey. “Then I realized the song was nothing without the bongos.” The demo for “Drive All Night” was sent off with the idea that they would strip back some of the more modern production elements and replace them with organic instruments. “We learned over the course of this project to send Aaron just the core of the song and then have us play off that, rather than the other way around,” says David.

TIDBIT: Recorded over several months in isolation, Come Morning nearly went off the rails after a less-than-successful session. “It gutted us,” says David. Once the band brought in drummer Aaron Sterling, the project took shape and pushed the brothers into a new creative space.

One thing that fans of the Bros. might be missing on Come Morning is an abundance of Joey’s down-tuned slide riffs. “Guitar playing wasn’t really a priority for me on this album,” says Joey. There are incredibly melodic moments with big, roomy sounds on Come Morning, but Joey’s focus was more on vibe and sound then trying to get his licks in. “I would go for my usual super-fuzzy solo and it just wasn’t as inspiring,” he remembers. “I found myself wanting different things and needing to change the approach.”

On his solo album Hindsight, a majority of the guitar tones were inspired by a very particular room reverb that Joey added pre-delay to in order to create a slapback effect. An early influence on this technique was Jimmie Vaughan’s 1998 album, Out There. “Jimmie’s tone is incredible, and that sound has an identity that’s congruent with the record. I’ve always tried to emulate that,” says Joey. That thirst for experimentation revealed itself when Joey looked to emulate the sound of his recording booth at Sandbox Recording, a studio that serves as the brothers’ musical headquarters. Their particular recording booth at the studio sounded so good, they wanted to use it on far more than just guitar and bass tones. “What wound up kind of being more of an identity on the record is that you can hear the booth on more instruments. You can hear it on the B-3, you can hear it on the vocal,” says Joey. He points to the acoustic guitar intro on “Back to Thee” as the best example of the sound. “It’s kinda like the Jimmie Vaughan thing. It’s not super in your face, but it’s a big part of the guitar sound,” says Joey. For the washed-out baritone guitar on “Corduroy,” they placed a mic in the airlock and left the door open just a crack. The resulting tone gave the illusion that it was recorded in a much bigger space. “We’re always trying to put mics in stupid places,” laughs Joey.

Joey Landreth’s Gear

Joey isn’t afraid to employ unusual textures with his parts. For example, here he’s using a Duesenberg 12-string Double Cat for some ethereal slide parts.

Photo by Mike Highfield

Guitars

- Sorokin Gold Top

- Josh Williams Mockingbird

- Duesenberg D6 Baritone

- Suhr Classic S

- Mule Resonators Mulecaster

- Collings OM1

- Waterloo WL-14 X

- Yamaha LS16M

- Yamaha Revstar

Amps & Cabinets

- Two-Rock Bloomfield Drive

- Two-Rock Joey Landreth Signature

- Greer Mini Chief

- 1960 Fender Super

- 1966 Fender Deluxe

- Two-Rock 212 Cab

Effects

- Benson Studio Tall Bird Spring Reverb

- Jackson Audio Golden Boy

- Isle of Tone Haze Fuzz ’66

- DanDrive Secret Weapon

- Mythos Pedals Olympus

- Ceriatone Centura

- Chase Bliss Thermae

- Chase Bliss Mood

- Chase Bliss CXM 1978

Strings, Picks, Mics & Accessories

- Stringjoy Custom Strings

- Rock Slide Joey Landreth Signature Slide

- The GigRig G3 Switcher and Power Supply•

- Moody Leather Straps

- Royer R-121

- Shure SM57

- Stager SR-2N

- Warm Audio WA-47

Typically, no matter where the journey takes Joey, he does have a few tried-and-true starting points. Most notably, his Sorokin goldtop and Two-Rock Bloomfield Drive is where he begins. But Joey isn’t afraid to swap out a trusted piece of gear if the vibe isn’t right. “The Two-Rock is a big sounding amp. If I start to play something and it takes up a ton of space and the part doesn’t need that, then I’ll start to reach for smaller amps,” mentions Joey. Those smaller amps include a Benson Nathan Junior, or a mid-’60s Fender Deluxe, which saw plenty of action on Come Morning. As a foil to the Two-Rock, Joey also employed a brown-panel Fender Super. “It’s kind of the opposite of a black-panel circuit. It has a lot more midrange and creamy breakup,” describes Joey.

“I would go for my usual super-fuzzy solo, and it just wasn’t as inspiring.” — Joey Landreth

Joey has also become well-known for his very particular setup on his guitars. He counts Derek Trucks and Sonny Landreth (no relation) as prime influences for moving to an open tuning. Trucks hangs out in open E (E–B–E–G#–B–E), while Sonny plays in several tunings including open A (E–A–C#–A–C#–E). However, it was an incredible Toronto guitarist named “Champagne” James Robertson who inspired Joey to not only eschew standard tuning, but to tune down to C. Robertson had such a unique style that Joey even texted him after a jam session to “get permission” to move to open C (C–G–C–E–G–C) exclusively. “I had a friend call this setup the autoharp of the guitar once,” remembers Joey.

David Landreth’s Gear

For Come Morning, both Joey and David didn’t stray too far away from their main setups. Here you see Joey with his Sorokin goldtop and David with his P-bass-style Moollon.

Photo by Jen Doerksen (BNB Studios)

Basses

- Moollon P-bass style

- Duesenberg Starplayer

Effects

- Noble DI

Strings & Accessories

- D’Addario Chrome XLs (.050—.105)

- Moody Leather Straps

Setting up a guitar for slide goes far past simply deciding on a tuning—finding the right string gauges is just as important. After moving up to a set of .014s for a while, Joey still felt something just wasn’t feeling right. He ended up with a custom set of Stringjoys that clock in at a whopping .019–.068. That sentence alone might make a guitarist’s hand quake with fear, but with the tuning’s lowered tension, the strings aren’t as rigid as you might think. All the guitars on Come Morning were in open C with the exception of a few acoustic parts in open D (D–A–D–F#–A–D), because Joey felt his Collings OM1 just really loves to live in that tuning. Every now and then when he’s working something out, Joey will hear a part that calls for standard-tuned voicings, “Sometimes I just need a few ‘cowboy chords,’ but then I tune it back to an open chord as soon as possible.”

Joey also favored a Josh Williams Mockingbird, which is a handmade 335-style guitar that’s loaded with Firebird pickups and is the “antithesis” of the Sorokin. “It has a bit of a mid-scoop, so it tucks in around a lot of the other guitar parts in a really beautiful way,” says Joey. “If I want something that’s not as mid-forward as the Sorokin and Two-Rock, but I don’t want it to be super scoopy, then I go with the Josh Williams into the brown-panel Super.”

One of Joey’s go-to combos is his P-90-loaded Sorokin with a Two-Rock Bloomfield Drive. “The Sorokin can be really aggressive, and forward, and present, and ... I would use the word triumphant. It’s like, ‘Here I am,’” says Joey.

Photo by Jen Doerksen (BNB Studios)

As much as Joey micro-manages his guitar tone—he even went so far to subdivide the slide vibrato on his Lowell George tribute record, All That You Dream—he couldn’t really do that as much on this project since there were so many collaborators and nearly all the bed tracks were done remotely. “I learned an incredibly valuable lesson on this record,” says Joey. “Which is to get the fuck out of the way.” The duo brought on Greg Koller to mix the album and he nailed more than half the mixes on the first try. “This album really feels different,” says David. “Maybe it’s the juxtaposition of the fact we made it in isolation and it being such a communal effort. There’s something about that I need to figure out.”

“Balance makes this whole thing feel a lot more sustainable and a lot less manic.” — David Landreth

So, is it a Bros. Landreth record if there isn’t a sense of fear and panic? “I think that’s the ultimate question,” says Joey. The brothers wear many hats including running their own record label, publishing company, and management company. “That balance makes this whole thing feel a lot more sustainable and a lot less manic,” mentions David. “Our creativity has many different outlets, so if I ever find myself with enough time to write more songs than I need, that probably means something bad has happened with the other things we do,” laughs Joey.

YouTube It

Featuring an expanded lineup that includes keyboardist Liam Duncan, the band tears through a handful of tunes from their sophomore album, ‘87.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.