On the phone from Dallas, where he’s prepping to hit the stage with his elite backing band, the Violators, Kurt Vile is musing over a question about the perceived sense of mysticism in his music, and how it might fuel his creative process. “Well, first I go down to the Shire,” he drawls wryly, pausing for effect, “and then I get a bunch of shiny stones….” He trails off in a brief fit of laughter, while down the Brooklyn end of the line, Steve Gunn joins him. “Yeah, I see it,” he gushes, and then just like that, we’re off on a multifarious tangent about lyrical poetry and hypnotic grooves—and how music, in the right moment, can induce an exalted state, in the listener as well as the performer.

“Just even picking up my guitar and playing a couple of chords can transport me,” Vile continues, his tone more reflective now. “It’s a state of mind, it’s a place, it’s a dimension, really. Music just does that, especially if you’re behind the wheel, driving it. All of a sudden, next thing you know, you’re spacing out for hours on the couch, even after just a couple of minutes. If you’re stressed out about shit, you can just play, and for a second your mind is completely changed. So yeah—it’s mystical.”

He and Gunn share another laugh. It’s testament to the bond they have as artists who don’t take themselves too seriously, but who nevertheless are seeking to remake—some might even say rescue—guitar-driven rock in their own implacably cool, blue-collar vagabond image.

For Vile, the journey is rooted in the country, blues, and bluegrass he picked up on as a kid. His first instrument was the banjo. Eventually he adapted some of the instrument’s open-tuned techniques to guitar, and developed a personal style that tapped into an eclectic range of musical influences, from Bob Dylan to Sonic Youth. After a short stint living in Boston, he moved back to his hometown of Philadelphia in 2003 and met singer-songwriter Adam Granduciel, who channeled his own obsession with Dylan into the War on Drugs—a band that, along with the Violators, lit fire to the city’s resurgent indie rock scene.

—Steve Gunn

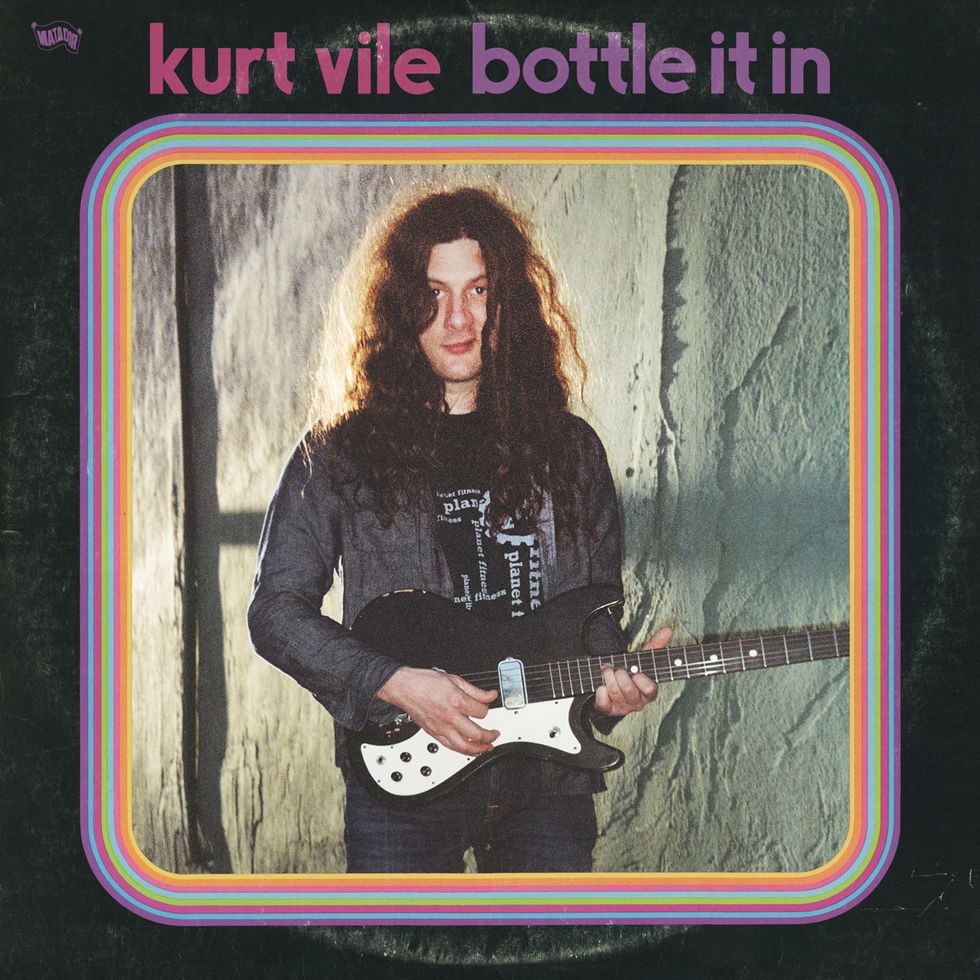

Bottle It In is Vile’s latest album with the Violators, and it captures a knockabout genius at his most freewheeling and comfortable. “Loading Zones,” a slacker ode to the thrills and spills of free parking in Philly, sets the tone early: Vile has a way of uncovering simple and ecstatic truths in his songwriting, whether he’s looking to “rip the world a new one” or, as he sings on the hypnotic jam “Bassackwards,” to “fill the void of a long night, unwatched by the sun.” Wielding his favorite ’64 sunburst Fender Jaguar and various Martin acoustic guitars, he builds layers of sound that push his coproducers (among them Peter Katis, Rob Schnapf, Shawn Everett, and bandmate Rob Laakso) to the limit, while also giving his band (Laakso, guitarist Jesse Trbovich, drummer Kyle Spence, and various distinguished guests) plenty of leeway to dig into the beating heart of a song.

Gunn picks up the thread again. “Do you know that Jackson C. Frank song—I think the lyric is ‘To sing is a state of mind’?” he asks Vile, referring to “Just Like Anything,” an obscure chestnut from the troubled folk singer’s 1965 debut album. “It’s such a beautiful concept. Certain music puts you in a certain state of mind, and for me, I definitely have to work to get there. When I first started playing, I wasn’t exactly practicing Van Halen riffs, but I would play things on repeat and try to get into my own head a little bit. Doing that really cyclical guitar stuff helps me to get into more of a meditative state to sing, or to think about what I want to write.”

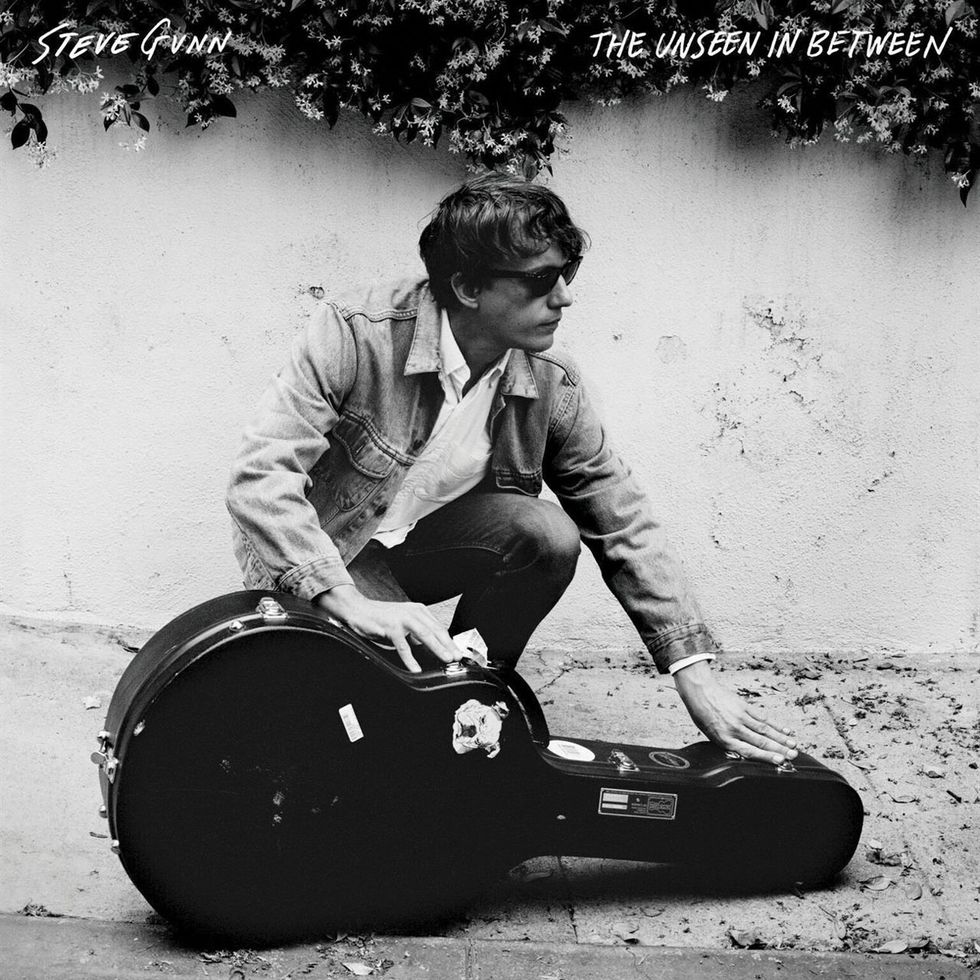

Gunn is also a Philly native, born and raised—as was Vile—in the western suburb of Lansdowne, and although he decamped to Brooklyn in 2001, his hometown is never far from his thoughts. “Stonehurst Cowboy,” from his new album The Unseen in Between, is a stunningly beautiful acoustic ballad dedicated to his late father and named for the neighborhood where his parents grew up. The song also channels Gunn’s deep connection to American Primitive and British folk music. After he graduated from Temple University, he lived in a house full of artists and musicians in West Philly where Jack Rose sometimes jammed, and where the records of John Fahey, Sandy Bull, and Robbie Basho were frequent staples. More recently, he has toured and recorded with British folk legend Michael Chapman. Chapman’s exquisite “comeback” album 50, produced by Gunn, is an unmitigated career milestone.

TIDBIT: Gunn’s new album can be heard as a catalog of his influences, from folk to free jazz to psychedelic rock.

Since 2007, Gunn has released more than a dozen solo albums and collaborations, including 2015’s Parallelogram EP with Vile, but The Unseen in Between, his second for Matador, is arguably his finest—and not just as a catalog of his influences, which range from folk to free jazz to psychedelic rock. Tracked in Brooklyn with an ace band featuring James Elkington (guitar and keyboards), TJ Mainani (drums), and upright bassist Tony Garnier (known for his long-running tenure in Bob Dylan’s band), the album flows with a sure-footed ease and a real sense of purpose. That intent lives in the tripped-out vibrato waves of “New Moon” (with a nod to Johnny Marr’s knack for thick guitar textures) and the folk-meets-Krautrock groove of “Lightning Field,” which finds Gunn laying into a complex open-D figure that helps steer the song into wide vistas of sound, reverberant and majestic, that recall the more orchestral efforts of the Velvet Underground or Pink Floyd.

“You know, they gave me your new CD the other day,” Vile reveals, regaling Gunn with recent tales of the road. “I started listening to it on the bus, and I smoked some weed because I hadn’t been drinking—and when I say weed, I mean, I can’t even handle the real action plants. Anyway, it sounded really good. I heard a few tracks and passed out, but I can’t wait to hear the rest. It’s atmospheric and beautiful.”

Gunn laughs again and graciously accepts the compliment, and for a moment the brothers-in-arms camaraderie that these two must have shared together on tour back in 2013, when Gunn joined the Violators to support Vile’s breakthrough album Wakin on a Pretty Daze, becomes palpable. Although they grew up just a few miles from each other, they didn’t meet for the first time until they were both established as rising stars, each with an eclectic arsenal of guitar chops and a fetish for vintage Fender gear and Martin acoustics. And now here they are, full circle.

You both went to the same grade school in Lansdowne, but do you remember when you actually met?

Kurt Vile: Well, I always forget about the time, but we did this thing with Meg [Baird]. It was sort of like a supergroup of Philly types doing all these songs. I remember we did “Street Hassle” by Lou Reed. My bandmate, Jesse [Trbovich] was in it, Meg, of course, and having Steve there was really nice. What did we do? We did “Street Hassle,” we did “They Don’t Know About Us.”

Steve Gunn: I think we did Big Star too.

Vile: Yeah, “Thirteen,” I think. You lived in New York by that time, but you were visiting Philly, and that’s how we really met.

Gunn: You know, the very first time I saw you play, and I made the connection that you were the same person from Lansdowne, was at Vox Populi [an artist-run event space in Philly]. I don’t remember if I even said hello, but I did buy a CD, which was Constant Hitmaker [2008]. I knew your name and I knew where your family lived. We never were friends then, but I made that connection. And then you also took lessons at Todaro’s, and I did too.

Kurt Vile had this old Kay revamped by Vintage Instruments in Philadelphia. He uses it to play “Wakin on a Pretty Day” onstage. Photo by Debi Del Grande

Was he a local guy?

Vile: Yeah, Todaro’s Music was in Lansdowne, where we’re from.

Gunn: I actually took bass lessons first, from a very polite metal dude.<

Vile: Oh, so you didn’t take lessons from Joe [Todaro]? He taught me banjo.

Gunn: I may have taken one or two lessons from him, but there was another guy teaching there. But I still go in there—the shop is still there.

How did growing up in the Philly area shape you both musically?

Vile: I get this question often, and it’s always a little hard to explain. But when I think of my music and when I think of Philly, some of it comes back to the Record Exchange. I would go there a lot, but I was shy and I didn’t know anybody by name. I was buying 7-inches and stuff. I remember vividly getting various Lou Reed records, from Street Hassle to Mistrial. And then in my 20s, there was a Siltbreeze lo-fi resurgence that came around, so that was influential in reconfirming my D.I.Y. thing, and that I should keep doing it.

TIDBIT: Despite the guitar he’s holding on its cover, Vile’s new album is mostly a field day for his Jaguars and Martins.

Gunn: My parents were super into music, and they grew up in an area of Philly near 69th Street, where there were a lot of DJs, mostly into soul and R&B music. And, you know, when you’re a kid approaching 15, 16, you have to make that weird decision: Do I want to play sports, or do I want to skateboard more? When I expressed interest in playing music, my parents were super supportive, so I just started playing incessantly. And I mean, I still crave that solitude, and locking yourself in your room and just playing and playing, and using your imagination in that way.

When I got a little older, I realized that Philly at the time had a lot of great radio programming. Temple had all these cool jazz programs, and Drexel University and WKDU. And my curiosity was just being pulled around by hearing jazz and all this different music.

You both have an exploratory approach to the guitar—especially with alternate tunings. How does that affect your songwriting, and are there particular players, like John Fahey, who drew you to this kind of experimentation?

Vile: Definitely. John Fahey was later, but being an easily influenced teen, I read some interviews in the indie rock world where they were using it, too. Pavement and Sonic Youth, obviously, were using all these different tunings, and they were influenced by Fahey, I guess. My dad would always play the old time stuff, and the banjo started that off for me, too. And later on, the Delta blues. You could make up your own tunings, or find out what tuning someone else used and try that.

Gunn: I think it sounds fuller if you’re playing solo with open tunings. You can get into the dexterity of your hands.

Vile: Fingerpicking and open tuning go hand-in-hand.

Gunn: Yeah. I just sort of wander around the neck until I think something sounds cool. Experimenting with that stuff, especially with capos—you can kind of find your key that you love to sing in, and focus on that. But now, I’m actually trying to get out of that. I’m almost in like a capo jail, or an open-tuning jail [laughs]. I’ve started trying to write songs more simply, with standard tuning.

Vile: It’s the same for me. I like to go with standard tuning now and just play rock ’n’ roll up onstage.

Guitars

Two 1964 Fender Jaguars (one for standard tuning, one for open tunings)

1966 Fender Mustang

1966 Fender Electric XII

1961 Guild Starfire

Fender American Original ’60s Jaguar

Fender American Vintage Jazzmaster

Greco “lawsuit” Les Paul

Martin custom 00 hybrids (from Fred Oster’s Vintage Instruments, Philadelphia)

Fender Palomino

Baxendale custom

Collings Waterloo

Martin DC-16RGTE (played live)

Gold Tone Paul Beard Squareneck Deluxe resonator

Buckeye 5-string banjo

Amps

1967 Fender Bassman

Fender Deluxe Reverb (blackface reissue)

Effects

Trbo Booster (designed by Jesse Trbovich)

Sovtek Russian Big Muff

Mountainking Electronics O.C.M. digital noise generator

Line 6 FM4 Filter Modeler

MXR M169 Carbon Copy

Dunlop Cry Baby wah

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXP14 Bluegrass light top/medium bottom (.012–.056)

Ernie Ball Beefy Slinky (.011–.054)

Do you each have a go-to acoustic you keep around for songwriting?

Gunn: I have one that just got smashed, which is unfortunate. Jet Blue, man—they got me. It was a Martin 000-18. It wasn’t vintage or anything, but it was nice and it was my main guitar.

Vile: Do you ever go to that place in Philly, Vintage Instruments?

Gunn: Yeah. That place is amazing.

Vile: They had Martin custom-make limited versions of some of their favorite vintage models. The one I have is the Philadelphia Folk Festival anniversary edition. That’s the first one I got—it’s all over Wakin on a Pretty Day. Then I have a newer one that’s more yellowish. They’re both my go-tos.

Gunn: Don’t you have one of those Baxendale guitars too?

Vile: I’ve got a couple of those. I love them. They take older, cheap guitars and make them nicer. I have a Kay dreadnought that I play on “Wakin on a Pretty Day” live. I keep that tuned a half-step down. Then I have a Silvertone I play on “Wild Imagination” that I keep tuned up a half-step.

You guys play a lot of different electric guitars, but can you talk specifically about the importance that Fenders, and particularly Jaguars and Strats, play in your sound?

Gunn: Well, I have a custom Strat made by Brian Haran down in North Carolina. He has a company called Fret Sounds. He put Lindy Fralin pickups in it for me and it sounds really good.

Vile: I’ve always been drawn to Fender, but it took me a while to realize that it was the Jaguar for me. I like the sunburst Jaguars, and then my bandmate Rob [Laakso] hipped me to the fact that pre-CBS is what I should go for. So I had a ’64, and then it just went from there. That was my main guitar starting around the Smoke Ring for My Halo album [2011], but by the time Wakin came around, I got another similar Jaguar so that at least with all the different tunings, I could use the same guitar if I wanted.

Do you both use Fender amps on a regular basis?

Vile: Yeah, I’ve got a ’65 blackface Deluxe. I’m not using that quite as much now, but when I play solos, I have a little brown Champ, like a ’58, and it’s my favorite sound. With the Jazzmaster or the Jaguar, it’s somewhere between the blues meets My Bloody Valentine.

Gunn: Yeah, I have a Deluxe, too. Over the years I’ve been getting smaller. I had a Twin forever, and then I got tired of carrying that thing around, so I got a Deluxe, and then I got a Princeton, and now I have a Champ, too. That’s a ’66 Champ that I really like.

Vile: I got a ’65 Vibro Champ a long time ago. It’s funny how you just go smaller all the time. And you realize then you can really push it in the house, you know?

Gunn: Oh yeah, and in the studio, too.

Does going smaller also make it easier to hear the band?

Vile: Well, I’m going deaf all the time, but I have in-ear monitors, which are really hard when you’re trying to feel like you’re actually playing music without feeling isolated. I finally found these in-ears that have holes in them, so you can hear what’s around you. You play really loud, honestly, if you don’t have in-ears. If you have them, you can play quieter on stage and push it in the house, but it’s not for everyone.

Although he also plays Martins, Gunn’s frequent acoustic companion is a 1970 Guild D-35, with a spruce top and mahogany back and sides. He describes the D-35 as “perfect for me.” Photo by Tim Bugbee/Tinnitus Photography

The two of you also write a lot about traveling and moving, and I wonder if some of your favorite songwriters deliver that for you.

Vile: You know, I love that song by Willie Nelson, “Still Is Still Moving to Me.” When I think about that, it’s sort of the same thing, like sitting on the couch while traveling a million miles in my head, or you could be on a bus that’s sitting still, but you’re still moving.

Gunn: Sometimes people tell me, “I don’t even listen to your lyrics. I just like the sound of your voice, because it takes me to this place.” Obviously I write and edit my words, and try to come up with concepts. I don’t want to say that I use poetry in my lyrics, but I try to use descriptive words that maybe help get someone thinking about not necessarily what I’m singing about, but stimulate their imagination by using more imagery in the words. But I was also thinking about how the voice can just set a mood, where you’re not riding on every word, but the voice is the focus. One of my favorite singers is Sandy Denny [from Fairport Convention], and just the sound of her voice sometimes makes me want to weep.

Vile: “Farewell, Farewell”?

Gunn: Yeah, and “Who Knows Where the Time Goes?” I mean, the lyrics are amazing, and I think she wrote that when she was really young.

When you work with a producer, what are you looking for and listening for?

Vile: Ideally you just want to find people whose sound you like. You always feel it out at first. I wanted to work with John Agnello a long time ago, and that was great—we did two records.

Then with b’lieve I’m goin down [2015], Rob Schnapf reached out, which was perfect because we had hit a wall. Then we ran out of time with him, and the record still wasn’t done, so Rob knew Peter Katis, and he rescued the record at the end and mixed it really fast.

So with the new album, we started with Peter, and then I went back to Rob, but I was curious to have one more sound—somebody who was painting with some different colors—so Shawn Everett’s name came up, and then he reached out and showed enthusiasm. Part of it is someone showing the enthusiasm, to want to do it. But it’s funny, I like to find multiple people within an album.

Gunn: I feel like I’m still learning. But this last record almost felt like a real session. It was a studio I had just visited, and the engineer, Daniel Schlett, had almost an old-school approach to recording, where it felt simple and you just wanted to focus on getting good sounds and not overdoing it.

Vile: The production is really amazing on that record.

Gunn: Oh cool, thanks. And another thing I did, that I hadn’t really done before—I just wanted to be comfortable. I get really nervous, and I always feel like I’m spinning my wheels.

Vile: That’s me, too, definitely.

Guitars

Custom S-style built by Brian Haran (Fret Sounds) with Lindy Fralin pickups

2017 Fender American Professional Jaguar

2014 Martin Special Edition 000-18 acoustic

1970 Guild D-35

Amps

1970s Fender Twin Reverb

1968 Fender Princeton

Fender Custom Deluxe reissue

1966 Fender Champ

Effects

Real McCoy RMC2 Wah

Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamer

EarthQuaker Devices Palisades overdrive

Electro-Harmonix Freeze Sound Retainer

Electro-Harmonix Soul Food distortion/fuzz/overdrive

Catalinbread Belle Epoch Tape Echo

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXP14 Bluegrass light top/medium bottom (.012–.056)

Fred Kelly banjo picks

Gunn: Yeah, and doing bad takes and wasting time, and then it’s like, “Hey, you know the clock’s ticking, we gotta get this fucking done!” So I really worked on singing and playing the songs a lot before I went into the studio. And then just kind of randomly, I linked up with Tony Garnier, who plays with Bob Dylan.

Vile: I’m stoked to hear about this!

Gunn: I ended up meeting him because he was working in the same studio the week before with Marc Ribot. And Daniel is a Dylan nerd like me, so he texted me and told me I should come by just to say hello. And Tony was just super-friendly and interested, and wanted to hear some demos. So he came in just to see how it might go, and he ended up playing on the whole thing. Tony was playing upright, and he had this really awesome electric bass—it was a 1959 Hofner, not a Beatle-bass, but a big-bodied one. These basses were a hundred years apart. I was like, “How old is that thing?” and he says, “It’s from 1859.” And he picked it up and goes, “Check this out,” and on the side in scripted pen, it says Charles Mingus. Apparently he doesn’t even tour with it because it belonged to Charles Mingus.

And it was so cool to have Tony there, because he basically was like, “Man, just be yourself and go sing the song, and we’ll play behind you.” He asked me to print out the lyrics, and he was really getting inside of the song, almost treating it as a song. I don’t know if that sounds weird, but I don’t think I’ve ever done that.

Vile: No, it only sounds weird when you’re making music in this modern world, where you’re always trying to get back to that. But with some people, it doesn’t even occur to them that’s the way it’s supposed to be.

Gunn: Yeah, it just felt really simple. Some of the guitar stuff I did was not as complicated as before, and I was like, “Oh, I don’t have to force it.” We were just doing whole takes and moving on, like the feeling you get from a live recording. What I’m getting at is, it was new to me to not be over-caffeinated and jittery and nervous and sweating and unsure of myself, you know? It just felt like the way that it should—or the way I imagined a lot of the records that I really love were recorded. Like with Dylan or Neil Young, you can just feel that they’re all in the studio. I think there’s something lost with a lot of music that comes out now because it doesn’t have that quality. Not to get too nostalgic.

Or mystical.

Gunn: Yeah, exactly!

Vile: We do that on a regular basis.

You can hear Kurt Vile, on guitar and banjo, and Steve Gunn, playing guitar, on their version of John Prine’s wistful “Way Back Then.” The performance is from their 2015 collaborative EP, Parallelogram. And yeah, the YouTube video title credits the wrong songwriter and omits Gunn.

Don't forget to check out Kurt's Rig Rundown.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)