“Don’t scoop your mids!”

It’s probably the most frequently dispensed pearl of tone wisdom on guitar forums—and one of the most vague. Midrange is a broad topic, literally and conceptually, and those words can signify many things. So let’s unpack the meanings of midrange in search of deeper understanding of how amp midrange settings affect your recorded tones.

Don’t Touch That Dial! No, Do Touch It! No, Wait—Don’t!

Naturally, the players who post those words usually refer to turning down the midrange knob on your amp. This is probably in reaction to sort of mid-scooped rock guitar tones that predominated in the ’80s and into the ’90s. Some engineers refer to this tone profile as a “smile curve,” because if you call it up on a graphic EQ with multiple sliders, the result looks like a grin. (I prefer a less common—but funnier—moniker: “stoner vee.”)

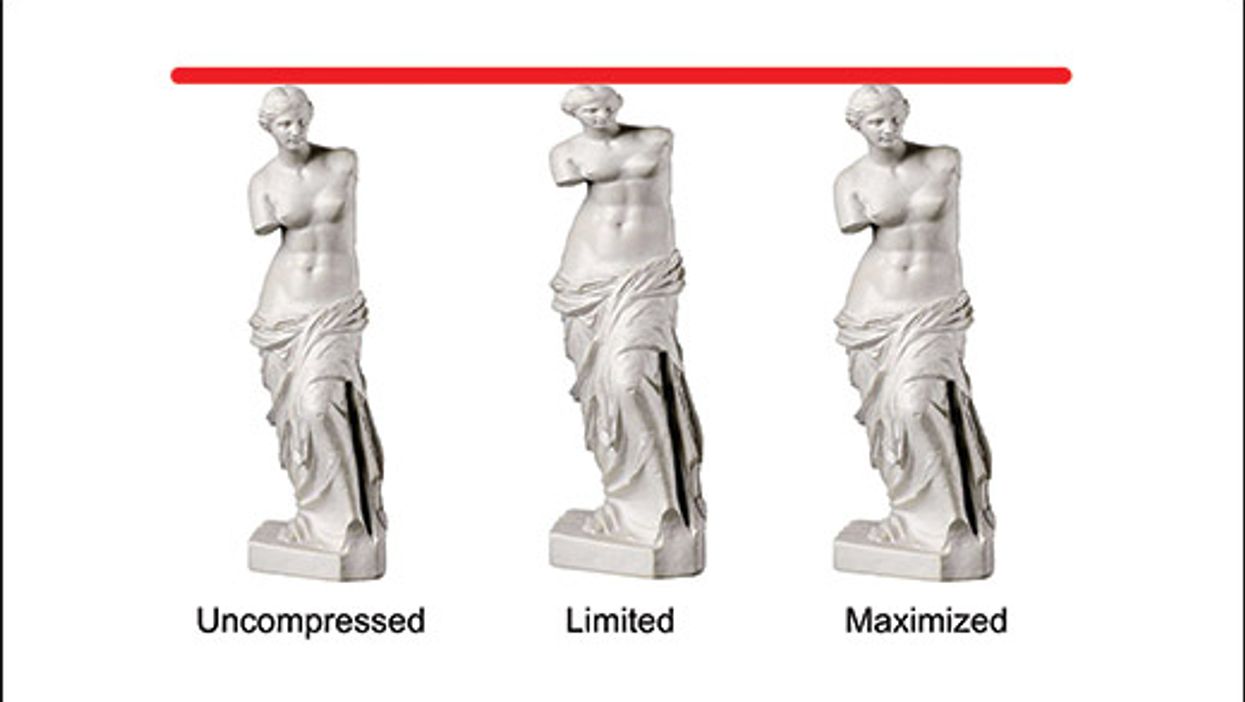

That ’80s sound—strong lows, hyped highs, and super-scooped mids—provides a certain cheap thrill, much like cocaine, the era’s studio drug of choice (or so I’ve been told). The sound can certainly grab your attention, though it isn’t a faithful depiction of a guitar’s innate sonic proportions (see artist’s conception in Fig. 1).

You can modify mids before the guitar signal hits the recording input, or after. We’ll look at precision DAW-based midrange sculpting in a future column. For now, let’s focus on upstream adjustments, especially amp knob settings. But first, a quick-and-dirty review of the relevant EQ lingo.

Frets and Frequencies

The hearing range of a healthy young person is 20 Hz to 20 kHz. The A = 440 Hz we tune to corresponds to the A at the 1st string’s 5th fret. Double or halve the frequency to shift by an octave: 220 Hz corresponds to the A at the 3rd string’s 2nd fret.

Amp tone controls are machetes, not scalpels.

The fundamental of the open 5th string is 110 Hz. The A string on a bass sounds at 55 Hz, as does the lowest note of a 7-string guitar dropped to A. Moving in the opposite direction, the 1st string at the 17th fret rings at 880 Hz. Meanwhile, the lowest frequency emitted by a standard-tuned guitar is E = 82.41 Hz.

Note that the scale isn’t linear: 110 Hz and 220 Hz are only 110 Hz apart, while there’s a 10,000 Hz difference between 10 kHz and 20 kHz. But both 110/220 Hz and 10/20 kHz are exactly one octave apart.

And remember, there’s more to EQ than target frequencies. Equally important is the bandwidth of the slice. Removing a narrow sliver at 500 Hz is a far cry from a broad swath that’s centered at 500 Hz, but which extends by multiple octaves in either direction.

One more thing: Electric guitar amps put out little signal above 4 or 5 kHz, as opposed to, say, pianos or cymbals, whose overtones extend to the top of our hearing range. Boosting or cutting highs above that point does nothing—unless the bandwidth is wide enough to affect frequencies below 4.5 kHz or so.

So what sorts of cuts and boosts do you get when you adjust a typical amp’s mid knob?

Midrange According to Jim and Leo

Let’s turn to a cool bit of free software: Duncan Tone Stack Calculator. (No relation to Seymour D.) It’s for PC only, but Mac users can run it via a Windows shell program such as the $59 Crossover from Codeweavers. It provides visualizations of such common tone controls as those on Fender and Marshall amps, plus that mother of all stoner vee curves, the original Big Muff.

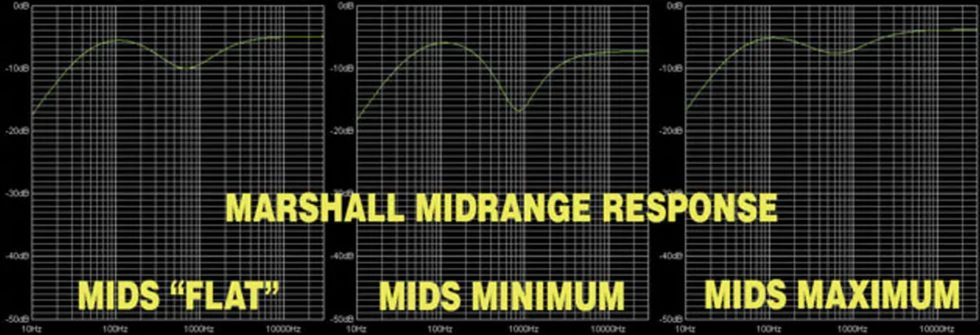

Fig. 2: The tone profile of a typical Marshall amp, with the midrange at 5, 0, and 10.

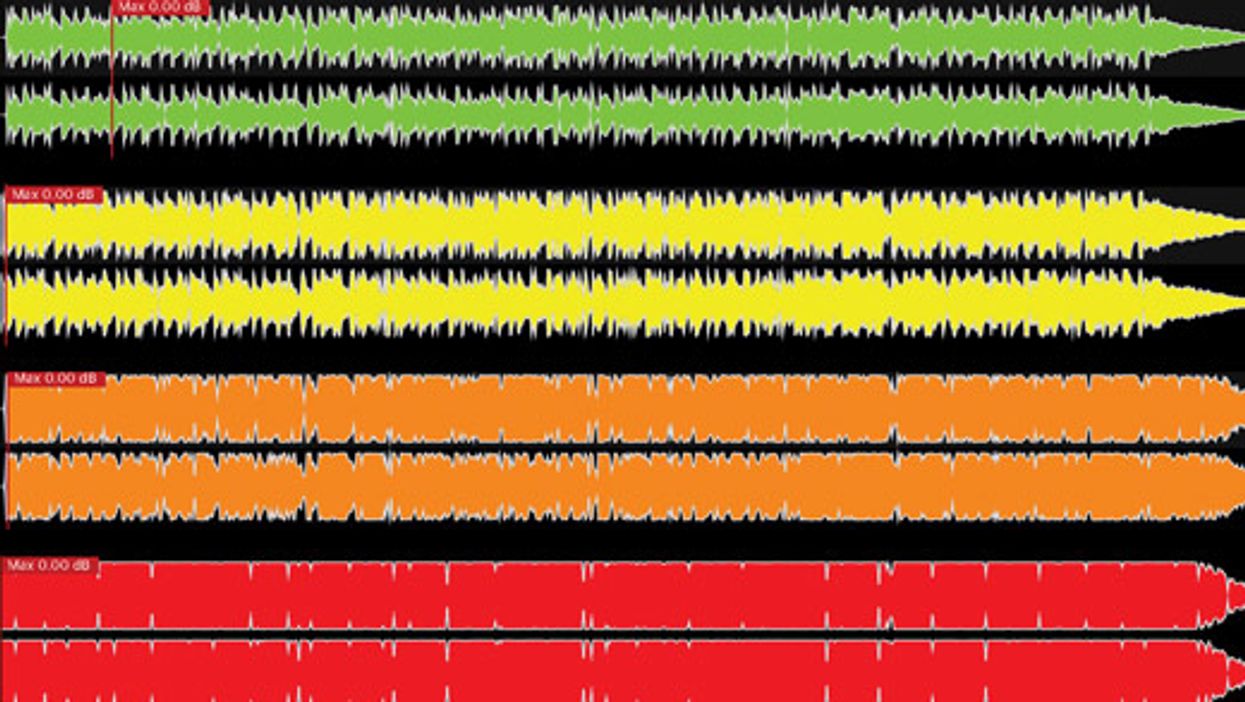

Fig. 2 shows the frequency curve of a typical Marshall amp with its mid control an noon, fully scooped, and cranked to the max. Lookit! There’s a big-ass scoop at around 800 Hz even when it’s “flat.” Hell, there’s even a scoop when it’s dimed! And when you lower the mids all the way, the distorted discus thrower in Fig. 1 starts to look like an understatement. It’s a wide scoop, too, affecting frequencies from about 100 Hz to 4 kHz — practically the guitar’s entire range.

Fig. 3: The mid cut on a typical blackface-style Fender amp is even more extreme than on a Marshall.

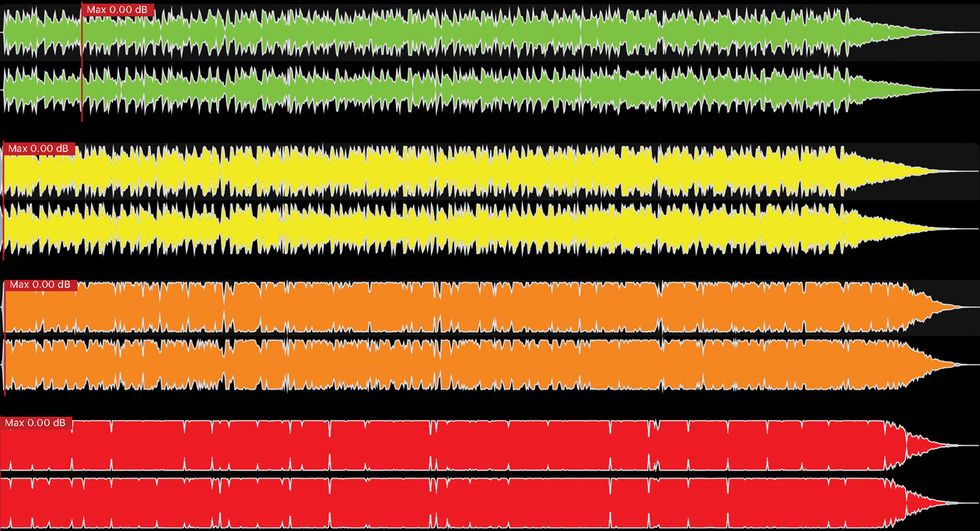

The typical Fender midrange profile in Fig. 3 is centered lower, around 500 Hz. Check out the middle image with its -35 dB cut, which also splashes across the guitar’s entire frequency range. It’s the Marianas Trench of midrange cuts! In fact, if you want to fake an amp sound using a direct-recorded guitar signal, your first needed adjustment is probably a similarly deep and wide EQ cut centered between 500 Hz and 1 kHz, even if you’re aiming for a fat-sounding tone.

Are Scoops for Poops?

So should you avoid scooping mids on your amp? Not necessarily. It depends on the context—duh! Judge with your ears, not the Duncan Tone Stack Calculator. But be mindful that if you nix major mids, it’s not just a bit of EQ nip-and-tuck—you’re disemboweling your tone like it’s a corpse on an autopsy table. Except amp tone controls are machetes, not scalpels.

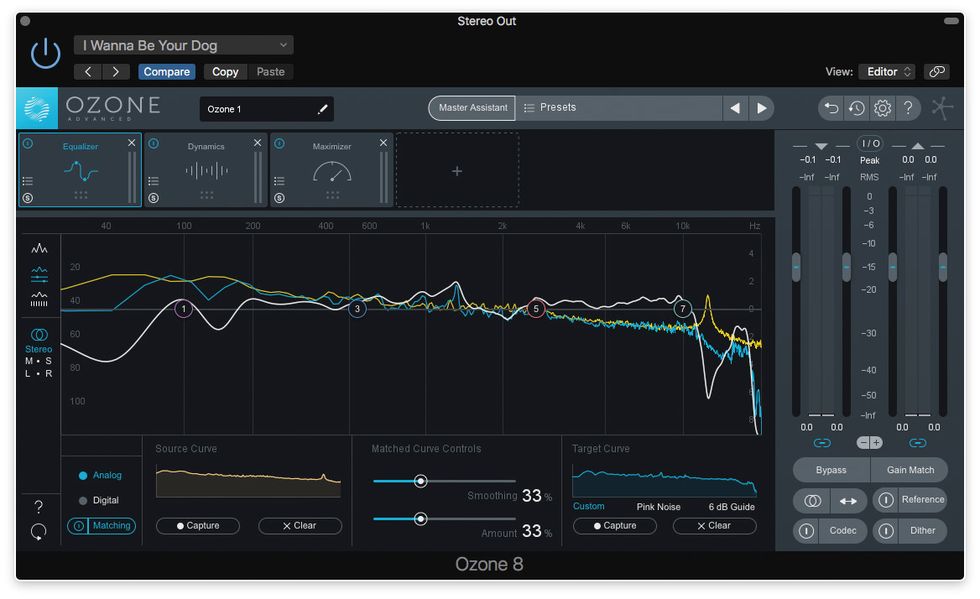

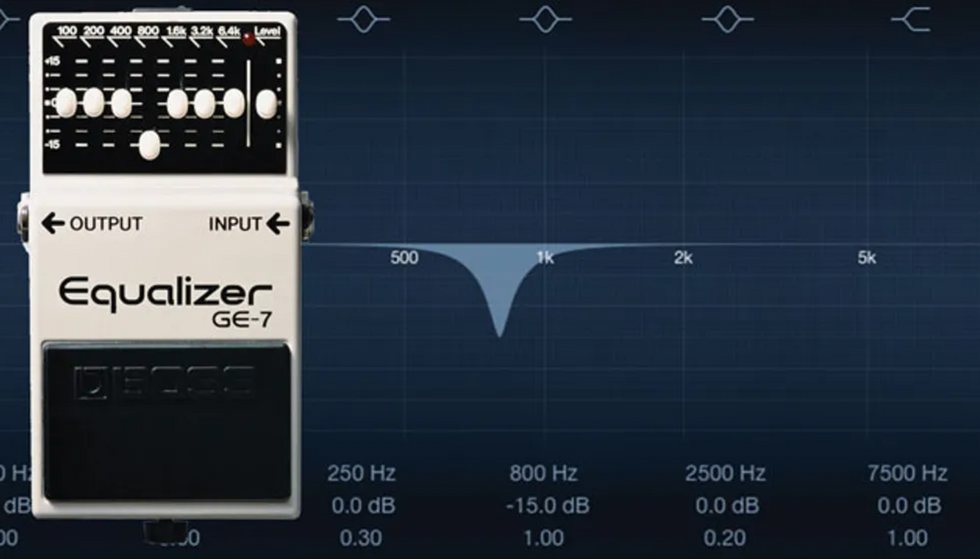

Fig. 4: Even a humble EQ pedal provides more precise midrange sculpting than most amp EQ knobs.

There’s another way to sculpt midrange upstream from the recording input: using an EQ pedal or similar device. Some of these provide parametric EQ (which means you can specify the bandwidth of the boost or cut). Even a humble Boss GE-7 Graphic Equalizer is surgical compared to amp controls. Here the fixed bandwidth spans about an octave, as opposed to the four octaves or more affected by typical amp midrange pots. (See Fig. 4, with the resulting EQ curve approximated in Logic Pro’s EQ plug-in). Even a maximum -15 dB cut at 800 Hz (roughly the Marshall midrange frequency) is far, far subtler than zeroing an amp’s mid control.

The real precision midrange sculpting is likelier to happen within your DAW—and we’ll explore those techniques in an upcoming column. Till then—it depends on the context!

[Updated 1/13/22]

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)