Hello and welcome to another Dojo installment. This month, I’ll share three simple secrets for getting better and more consistent mixes. In the ever-changing world of mixing music, engineers are constantly having to refine their chops while still being acutely aware of current trends, past traditions, managing expectations of artists—all while adding and refining their own contribution to recordings.

Regardless of musical genre, I’m often asked, “How do I make my mixes better?” I usually respond with “it depends.” Mixing isn’t math, there is no theorem or equation that will give you a precise approach. It’s about emotion. Your job when you’re mixing is to bring final focus and attention to fluid, emotional moments by guiding the listener on a highly curated journey. How can we even begin to approach this abstract goal? Tighten up your belts, the Dojo is now open.

Let’s assume you already have an intimate knowledge of what the vision is for the song or album. This is a crucial step! It’s one that I spend a great deal of time developing. I passionately feel that artists and bands deserve a mixer who is completely committed to their vision, and can add deep, meaningful contributions to their recordings while still being an objective voice that can bring an extra bit of magic to the project. Don’t start mixing until you’ve done your homework and really understand the profound level of sacrifice that artists go through to make their music. You should feel the honor and responsibility that is involved as well.

Your job when you’re mixing is to bring final focus and attention to fluid, emotional moments by guiding the listener on a highly curated journey.

Now here are those three secrets for better mixes:

1. Who’s on Bottom?

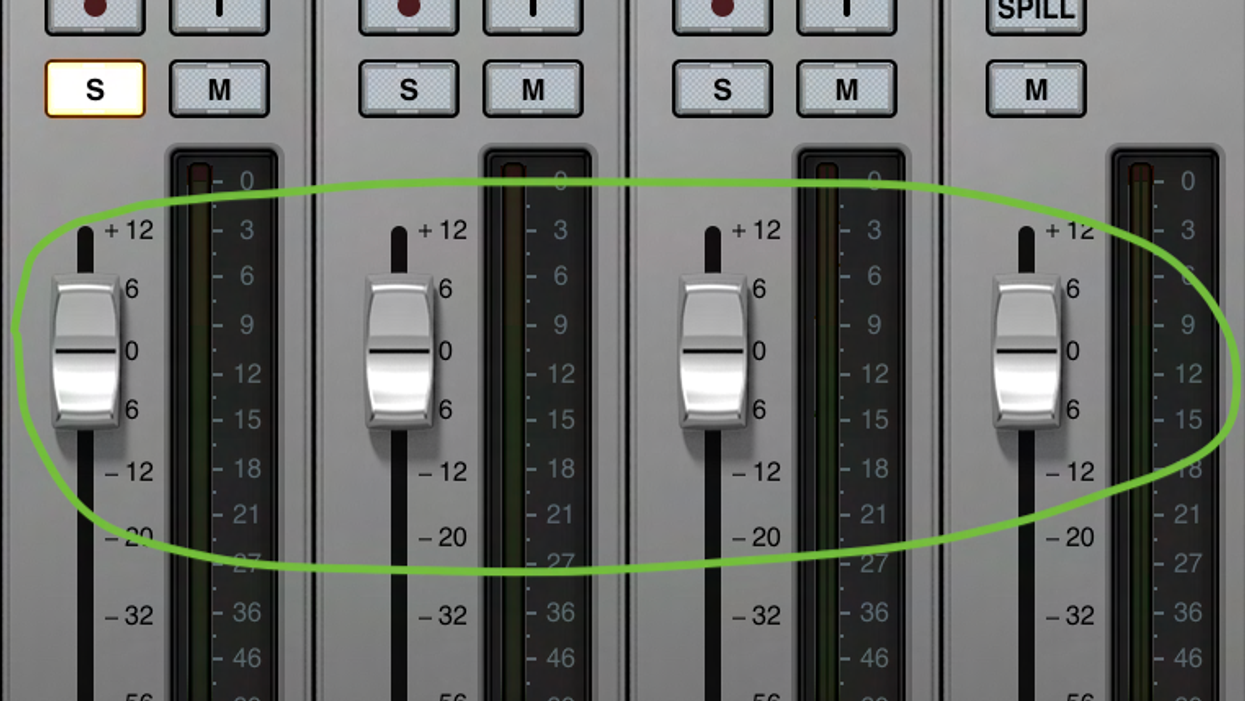

My main goal is to get to the emotional core of the song as soon as possible. On first listen, I’m not worried about “is the hi hat too loud?” I bring the faders up to unity, as seen in Fig. 1, and just listen.

On the next listen, I get basic levels and determine which instruments are important in which sections. Quickly, I address the genre and determine “who’s on bottom.” There are usually two choices: bass (or synths or low-tuned, 8-string guitars) or the kick drum. Musical genres have certain expectations. For example, hip-hop and rap typically reserve the bottom end of the frequency spectrum for kicks and tuned 808 tones, while heavy rock usually wants the guitars in the bottom with just the attack of the kick drum above for articulation. Your understanding of this and the artist’s tolerance for how far they’re willing to push these expectations will help you decide. This doesn’t mean the values can’t switch based on certain sections of the song. I do this quite a bit, but overall, there should a clear winner and a clear approach.

2. Less Is More

Fig. 2

When using EQ, employ it to cut problem frequencies. Far too often, folks boost frequencies of what they want to hear rather than going in and notching out problem areas. That results in everything getting louder and the problem areas don’t go away. Does the kick drum have a ring to it? Go find that frequency by sweeping a gained-up, narrow Q point across the frequency spectrum [Fig. 2] until you find the ring—and then cut it!

Fig. 3

The same can be done for shrill guitars, bass-heavy percussion, muddy keys, and particular notes of the vocal that really jump out and sound strident. Remember to boost with a narrow Q, sweep, isolate, and cut [Fig. 3].

3. Beware the Buzz Cut

Don’t overdo compression. Most of the time when I use compression, I’m getting anywhere from 2 to 10 dB of gain reduction. Anything over that, and I need to have a valid reason why (squashing a drum kit, pinning a background vocal or synth, etc.). Try to preserve as much dynamic range in your mix as possible and your audience will be able to climb in the mix more, and their ears won’t be fatigued.

Fig. 4

Take a look at a classic 2000s loudness war mix in Fig. 4. See how the music has a “buzz cut?” There’s hardly any dynamic range. Everything is loud!

Fig. 5

Now look at Fig. 5. This a classic heavy metal song, and look the dynamic range.

FYI, Apple Music, Spotify, and others are really rewarding mixes with greater dynamic range, and if their algorithms determine your mix sports a buzz cut, they will lower your loudness level anyway, thus foiling your dastardly plan to win the louder-is-better contest.

Blessings and, until next time, namaste.