The great American journalist Hunter S. Thompson famously said, “When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro." So, heeding an expert's advice, when we went looking for the world's weirdest guitar mods and builds, we turned to the pros—guitarists and builders with an otherness to their aesthetic sensibilities.

We found a sampling of some truly outstanding and uncommon instruments made or modded by a diverse group from the U.S. and abroad, and from urban and rural locales. Some are famous; others obscure. A few are deceased. But all of these axes reflect their highly personal vision of what a guitar can do, or even be. So let's dive into a mind-expanding trip into the world of beautiful fretboard weirdness.

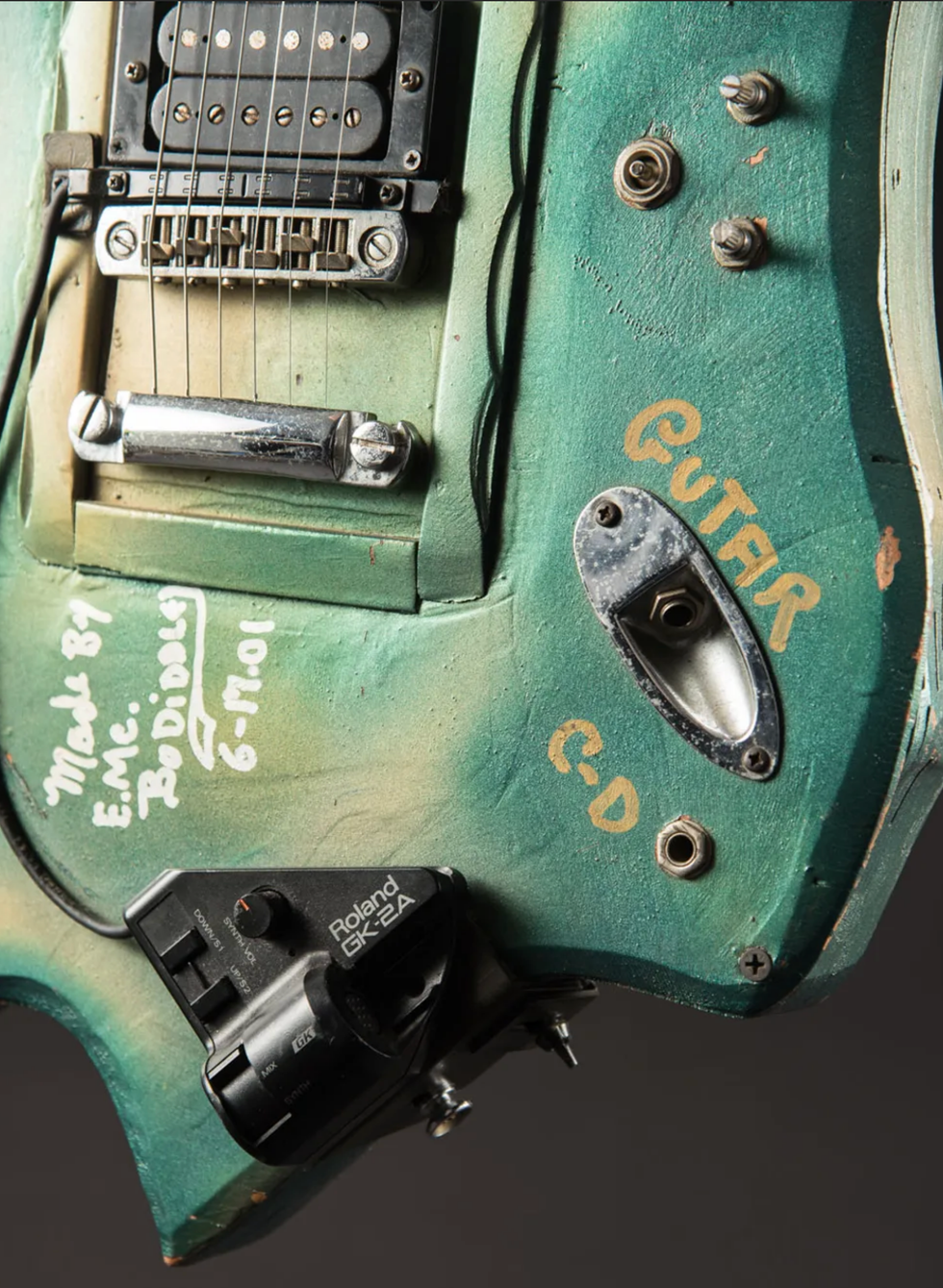

Bo Diddley's Amoeba

Photos by Jonathan Roncolato/Carter Vintage Guitars

Bo Diddley was no stranger to guitar building, but it's hard to find conventionally played guitars stranger than Bo's. This axe's amoeboid shape reminds me of the tentacled menaces from the 1968 science fiction film The Green Slime. Even the color exudes a kind of alien putrescence. And while the neck feels and plays killer, this is, indeed, a spacey beast.

Photos by Jonathan Roncolato/Carter Vintage Guitars

The foundational rock 'n' roll giant built his first truly playable homemade axe in 1945, fashioned from a cigar box, and he continued to build guitars from slabs of wood and whatever crossed his workbench for the rest of his life. He also commissioned creations. One of the more famous is a drum machine with a Fender Stratocaster built into it. The guitar is now M.I.A., but you can find a photo here.

Photos by Jonathan Roncolato/Carter Vintage Guitars

After his clave-based Bo Diddley beat became a staple of rock guitar via a series of hits starting with 1955's "Bo Diddley" and '56's "Who Do You Love?," Bo convinced Gretsch to expand his love of cigar box guitars into a full-sized, rectangular signature model: the famed firebird red G5810. Altogether, there have been seven differently numbered box-like Gretsch Bo Diddley models over the years. The original is featured prominently on the cover of his 1960 LP, Have Guitar Will Travel.

Photos by Jonathan Roncolato/Carter Vintage Guitars

In '59, Diddley induced Gretsch to also make the G6199 Jupiter Thunderbird model—another oddity with a scooped tail and lower end that Diddley requested because he felt the wider body of his Gretsch 3161 got in his way. Its latest iteration is Gretsch's Billy-Bo, based on an example Diddley gifted to Billy Gibbons.

Photos by Jonathan Roncolato/Carter Vintage Guitars

The evidence of Diddley's passion for building and commissioning oddball 6-strings is in photos all over the internet. And it's also now on the wall at Nashville's Carter Vintage Guitars, where the 2001-built amoeba guitar hangs with a $30,000 price tag.

Photos by Jonathan Roncolato/Carter Vintage Guitars

Its lines are less-than-elegantly carved, and the body is plywood with a plywood top that's mounted in place by wood screws. The weight? Well, it seems heavier in my hands than my '68 Les Paul, which comes in at 12 pounds.

Photos by Jonathan Roncolato/Carter Vintage Guitars

Besides the CD player—which works—the other sound sources are a pair of humbuckers and a Roland GK-2A synth pickup. The Lotus neck is key to the guitar's playability, and its tuners hold their ground, making this green alien more functional than might be anticipated.

BO DIDDLEY 1965

Here's Bo Diddley rocking like a damn freight train on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1965, with one of his specially sculpted Gretsch Jupiter Thunderbirds.

Lewis Waters' Harmonic Hot Rods

Harmonic Isolator

Blend a guitar with a celestial choir, a Theremin, chimes and bells, and a synthesizer and you'd be merely approximating the near-mystical tones created by the instruments Lewis Waters builds in Perth, Australia, under the New Complexity name. For nearly a decade, Waters sought to expand the sonic palette of his conventional 6-strings with pedals and amps and extended technique, both solo and in bands. But, as he explains, the sounds he was hearing in his head were calling for something more organic—a fresh take on the instrument itself.

Inspired primarily by the improvising guitarists and instrument creators Hans Reichel and Yuri Landman, Waters was determined to build the guitars he imagined. (Check out Landman's step-by-step instructions for recreating the drone guitar he built for Thurston Moore, in our May 2016 issue.) First, Waters enrolled in a two-year course in woodworking, while continuing his research into pickups, sustainers, tuners, bridges, and other elements essential to his vision. Then, seven years ago, he began simultaneously building two of the guitars he imagined: the Harmonic Master and the Harmonic Isolator. The sounds both make are otherworldly and solidly of the guitar at the same time.

New Complexity - Harmonic Isolator Demo

Harmonic Master

The Harmonic Master has an extended bridge that adds an independently tuned harmonic overlay to the notes played on the instrument's neck. And thanks to a behind-the-bridge pickup, the resonating notes in that independent section can be separately amplified. With two string fields, there's a lot going on, but Waters covers all of it with volume controls for each side of the bridge, a 3-way switch for the standard neck and bridge pickups, three output jacks (for guitar only, harmonic tones only, and a mix of both), and pickups by Lace Sensor. The body and neck woods available for all his guitars are Queensland maple, Tasmanian blackwood, and alder. Plus, the Harmonic Master can be ordered with a tremolo arm.

The Harmonic Isolator is a sonic step up from the Master, thanks to the inclusion of a Sustainiac electronic string sustainer and frets calibrated specifically to encourage harmonic resonance, inspired by the designs of the late and wildly inventive Hans Reichel. Those atypically spaced frets correspond to the notes in the harmonic series.

New Complexity - Harmonic Master Guitar Demo

This guitar has the same three-output-jack array as the Harmonic Master with volume controls for each side of the bridge. There's also an on/off toggle for the Sustainiac and a push/pull control for the device's four modes. In addition to the Sustainiac pickup in the neck slot, there are two Lace Sensor pickups between the guitar's two bridges.

This Reso Harp Special increases the harp portion's string array from the Reso Harp's 10 to a dozen.

Waters' third creation is the Reso Harp, which has an onboard fully tunable string reverb for creating yet another variety of intoxicating soundscapes. Essentially, the string reverb is a mini-harp-like configuration of strings adjacent to the six strings aboard the guitar's neck. Thanks to a Sustainiac, the harp strings can either resonate with the string vibrations generated by playing the instrument conventionally or they can be plucked as their own sound source. Again, there are two volume controls for each side of the central bridge, a 3-way toggle for the standard neck and bridge pickups, the sustainer on/off switch, and the push-pull for its four modes. There are four Lace pickups in all, to cover the guitar and harp portions of the instrument. Also, the Reso Harp has the same three output jacks as its cousins. And it's worth mentioning that Waters makes a hybrid version, blending elements from all three guitars and including a pickup just over the nut, à la Fred Frith.

Demonstration | Harmonic Master Reso Harp Hybrid by New Complexity

Capable of putting out four signals at once, the Harmonic Master Reso Harp has the greatest sonic potential of New Complexity's current offerings.

Reso Verb Prototype

Whether your musical tastes run toward an early gospel-blues blind cave fish like Washington Phillips or an avant modernist like Henry Kaiser, it's obvious a resonating harp offers a lot of potentially interesting textures, tones, and pads onstage and in the studio. So the ceaselessly exploring Waters is about to unveil a standalone version of the string reverb section of the Reso Harp, called the Reso Verb.

It's a box with 10 strings and two pickups—one sustaining—and volume controls for the input and reverb levels. There are input and output jacks, and dials marked treble, bass, and phase. It also has an insertable bridge, so players can create their own harmonic ratios. Heck, you don't even need a guitar to make cool sounds with this box. Any instrument with an output could be plugged into the Reso Verb.

Not surprisingly, New Complexity guitars are labor intensive. It takes Waters 200 to 300 hours to make each one, although he's contemplating ways to create his own version from stock parts in the future. For the average guitarist, getting a handle on playing one of his creations might also require many hours of study and practice. In addition to mastering the two-sided bridge concept and the harp-like approaches required to bring the most from these guitars, tuning is subjective. What's most important, says Waters, is that the harmonic ratios for creating overtones are locked in.

Vaughn Skow's 5-Pickup Frankenstrat

We've all seen Frankenstrats before, but the wall-to-wall pickup configuration on this beast looks like something hatched in one of Kenneth Strickfaden's mad-scientist-movie laboratories. In fact, it was brought to life in Nashville by pickup maker and amp builder Vaughn Skow, who's also got a long resume of sessions, TV work, and production.

"I was worried at one point that a wall of pickups would seriously dampened sustain." —Vaughn Skow

Skow purchased this Japan-made '62 reissue Strat about 15 years ago and started tinkering immediately, although he wasn't its first modder. The guitar came with a roller nut and Sperzel tuners, and, more important, a Seymour Duncan mini-humbucker in the neck slot and a Duncan Hot Rails in the bridge, plus the usual Fender single-coil in the middle. "I started messing with the pickups as soon as I got home, because that's kind of what I do," Skow says. "I like buying guitars that are good, but are already a little messed up so you don't have to worry about doing anything you want to them.

"I liked those pickup flavors, though I missed the honest-to-goodness single-coil sounds of a Strat. But I liked the sound of the Hot Rails, too, because they're a really mid-forward pickup, in the 200 Hz to 400 Hz range. So I decided to put one of my single-coils in next to the Hot Rails. "The body already had an ashtray routing done, so I started thinking about adding a single-coil to the bridge as well," he continues. "The idea became to get as much tonal versatility as possible from a single guitar. I was worried at one point that a wall of pickups would seriously dampen sustain, but then I figured that 3-pickup Les Pauls have a solid wall of pickups from the bridge to the neck, so why not?"

Once all five pickups were in place, Skow swapped the tone control closest to the bridge pickups for a toggle switch. Now, when the guitar's 5-position switch is in the bridge or neck spots, that toggle can activate or deactivate the single-coils. The finishing touch was replacing the Fender bridge with a Wilkinson VS100, and the guitar has been Skow's No. 1 ever since.

Of course, the inveterate experimenter has gone on to many other mods. Recently, he's been in demand among Kay archtop collectors for the minimally invasive pickup install he's developed, and for installing T-style pickups on banjos.

Vaughn Skow 1959 Historic Stratocaster Pickup Set - Jazz

Here's a demo of Vaughn Skow's vintage single-coil Strat-style pickups, which he added to his '62 reissue's three existing pickups.

John Cipollina's Horned Stack and Batwing SG

Photo courtesy of johncipollina.com

The lead guitarist and cofounder of Quicksilver Messenger Service may be the granddaddy of electric-guitar-era mods. By 1965, when the band was emerging as a leading proponent of San Francisco's psychedelic sound—alongside Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother and the Holding Company, and the Grateful Dead—John Cipollina was already using a ferocious assembly of combos, heads, and horns to amplify his guitars. And his famed batwing SG—named for its custom pickguard—was wired to send separate signals to bass and guitar amps, so he could cover the sonic waterfront.

His amp setup and the batwing SG were, until recently, on view at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame for many years. And they were designed to be inseparable. The stack—a blend of tube and solid-state power—consists of two Standel bass amps, a Fender Twin Reverb, and a Dual Showman head that drove six Wurlitzer horns. Cipollina used a footswitching system for reverb, tremolo, an Astro Echoplex (to the right of the Twin, in the photo), a Standel Modulux vibrato, and the horns. Truck running lights indicated which elements were in use.

"I like the rapid punch of solid-state for the bottom and the rodent-gnawing distortion of the tubes on top." —John Cipollina

Not only the batwing SG, but all of Cipollina's guitars had the split bass/guitar wiring setup. I'm not clear exactly how the wiring worked. Was it bass and guitar pickups in the different slots? Did he simply have specific routing for each pickup? The details at johncipollina.com aren't illuminating and efforts to contact a spokesperson for the late guitarist's legacy were fruitless. Nonetheless, what is clear is that one pickup's signal hit the two Standel bass amps supporting the stack. The other went to the Twin and the Dual Showman, and one of the pickups was reversed.

Cipollina's oft-quoted summation of his setup's strategy is simple: "I like the rapid punch of solid-state for the bottom and the rodent-gnawing distortion of the tubes on top."

Who Do You Love? (1973 B&W) - Quicksilver Messenger Service

With his batwing SG, John Cipollina and Quicksilver Messenger Service go full-tilt psychedelic in this live 1973 performance of Bo Diddley's classic "Who Do You Love?" at San Francisco's Winterland Ballroom.

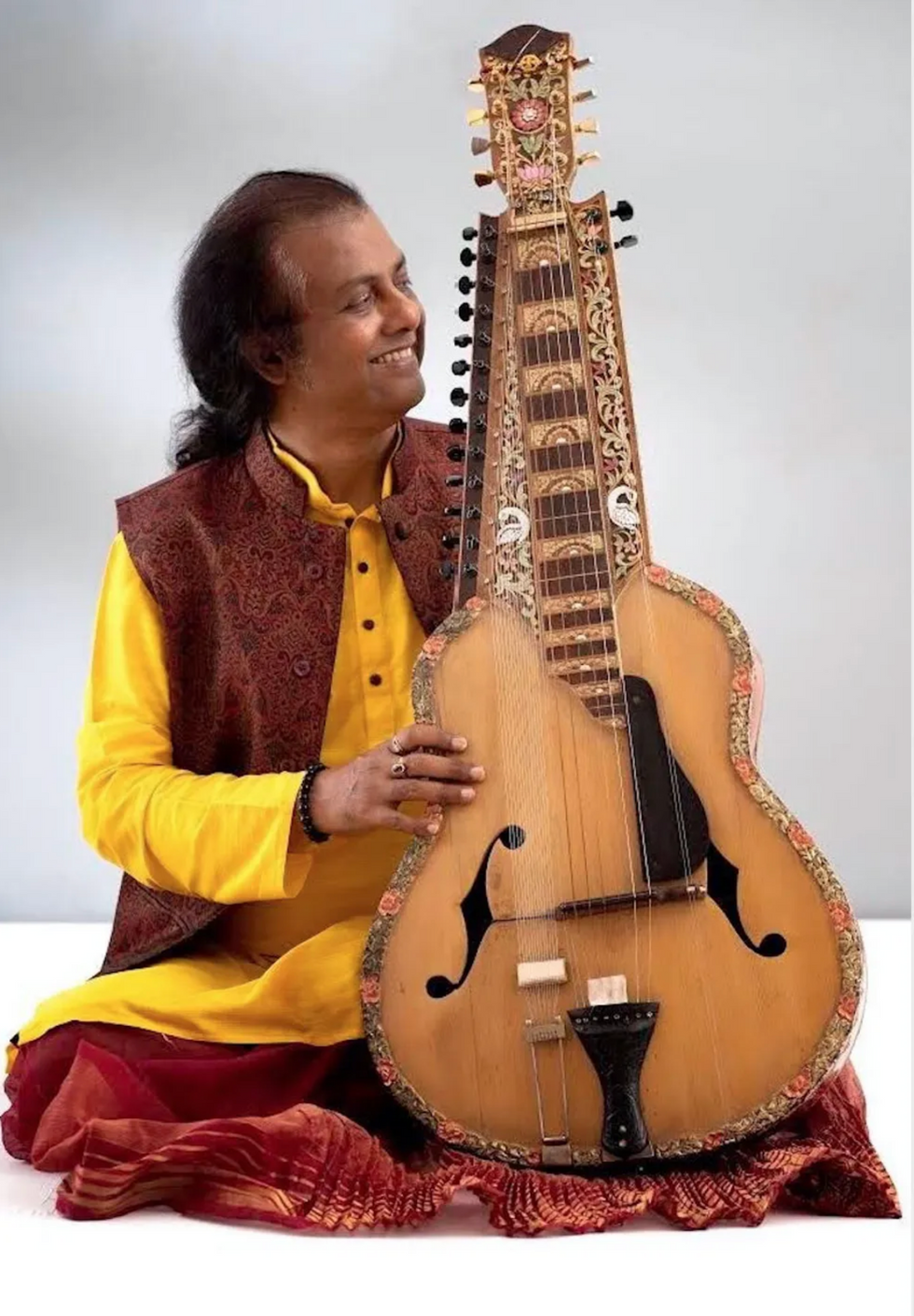

Debashish Bhattacharya's 22-String Slider

At first listen, the Chaturangui sounds like a cross between a slide guitar and a sitar, but its inventor, Debashish Bhattacharya, explains that it is, indeed, a guitar. It certainly looks and plays like one, with a tone bar—albeit a guitar that's grown a multiplicity of strings and some of the sweetest decorative work ever set to an instrument. And the Chaturangui has become a cornerstone in Bhattacharya's pioneering development of the genre of Hindustani slide guitar. It is indisputably a thing of great beauty, sonically and visually.

This 22-string instrument's invention, Bhattacharya says, began gestating when he was 3, after his mother gave him a solid-neck Hawaiian-style lap-slide guitar. "Since then, the lap guitar and me have been inseparable," he says. But the Hawaiian guitar didn't allow the long sustain, swelling overtones, percussive attack, and wide variety of sounds he was hearing from the long-established instruments in the South Asian musical tradition, like the sitar, sarod, violin, and veena. In search of those sounds, he began drawing out plans for the Chaturangui and built his first model at age 15, in 1978. This was not an easy task. "I had to get information on building this instrument in a world where Wikipedia and Google did not exist," he relates.

"The Chaturangui allows me to do at least a dozen things that can't be dreamt of with a 6-string Hawaiian guitar." —Debashish Bhattacharya

Initially, he was rebuked for his invention by both the Indian guitar establishment and the raga community. But as his career progressed, Bhattacharya won an international following for his wildly inventive playing, with John McLaughlin and Jerry Douglas among his fans and collaborators.

The hollowbody Chaturangui has a solid Poma toon neck. The sides and backs are made of mahogany and Poma toon, and the top is Canadian spruce. It sports brass frets and a resonating bridge made of deer horn. The carving on the neck and fretboard are done in yellowwood. Eight strings extend to the headstock. Six are melody strings played with a tone bar and the two on the bottom are used for low, percussive tones.

Two additional strings on the top—set apart from the neck—are plucked for high percussive tones. These are called chikari strings. A dozen sympathetic strings are set apart from the neck on the opposite side from the chikari. These can simply resonate with the melody or be raked. And the neck is scalloped, which allows the microtonal inflections and bends that give the Chaturangui its sitar- and sarod-like qualities.

"The Chaturangui allows me to do at least a dozen things I do, including tone modulation fingerpicking and resonating sounds that can't be dreamt of with a 6-string Hawaiian guitar," says Bhattacharya.

He's remained ceaselessly inventive as both a player and a builder. Nine years after making his first Chaturangui, Bhattacharya modified a Hofner guitar that was a gift from his guru, Ajoy Chakrabarty, into a Chaturangui-like instrument he simply calls a Hindustani slide guitar. And he's planning to debut a new instrument design at the 2019 Calcutta International Classical Guitar Festival on November 30.

Indian Slide Guitar | Pandit Debashish Bhattacharya | Raag Shuddh Sarang | Music of India

Debashish Bhattacharya takes on a traditional Indian raga with his Chaturangui at London's Queen Elizabeth Hall with Yogesh Samsi on tabla and Unnati Dasgupta on tanpura.

Elliott Sharp's Two-Headed Transplants

Elliott Sharp, who was profiled in the April 2019 issue of Premier Guitar, has been a leader in the international cutting-edge music scene for 40 years. The New York City-based virtuoso has also been an inventor of unconventional instruments, largely motivated by necessity, since 1969. He refers to his creations, like the 3-string violinoid and the triple-course bass pantar, as "proof-of-concept prototypes."

"The metal body is the top from a 50-gallon sweeping compound can that I had found while walking through Chinatown." —Elliott Sharp

Two of the most practical and intriguing instruments I've seen Sharp play over the decades are his bass/guitar doublenecks. Sharp explains: "Doubleneck 1 was built to my specs in 1984 by Ken Heer [ of now-gone St. Mark's Music Exchange]. I had been using both bass and guitar in my band I/S/M from 1981 to '83, and then with Carbon from 1983 on, and wanted to combine them."

Sharp determined the hybrid would be compact and headless, with a Schecter Strat neck and a medium-scale Fender Coronado bass neck—both with the headstocks removed. The pickups: a Fender Tele bridge and Strat neck, and a DiMarzio P Bass and J Bass set. There are no volume or tone controls—only 3-way switching for each of the necks with the outputs routed to effects through individual volume pedals. There is also an IVL hexaphonic pickup on the guitar that fed an IVL Pitchrider 7000 guitar-to-MIDI converter through a 13-pin cable, to trigger samples or interface with the interactive composition software, M. The body is laminated rosewood, maple, and mahogany. In 1992, it was painted black by New York City-based producer and guitarist Doug Henderson, who also added the aluminum pickguard and roll bar.

Sharp's Doubleneck 2 was built in 1992 by Henderson. "While I very much liked the bass on Doubleneck 1, the guitar was less centered in its tone, which would be remedied with Doubleneck 2," says Sharp. "The body is African limba with a bird's-eye maple top. Again, a Schecter Strat neck was used, but a Fender Musicmaster bass neck went on the low-end side. Pickups were DiMarzio all around—three Strats plus P and J bass units—and the bass bridge is a massive Wilkinson. The guitar bridge is of unknown origin, but made of brass and very solid. Doug used deck plate for the pickguard. Again, there were no onboard controls except for switching: 5-way on the guitar and 3-way on the bass. The necks were each routed to effects through individual volume pedals. There was no MIDI pickup."

But wait! There's more. Versatile and powerful as they are, these doublenecks are not light. Just look at their slab bodies. "By 1996, the doublenecks—not to mention their associated effects racks—were taking their toll on my back, so I decided to create a compact 8-string extended range instrument," Sharp recounts. That's the Henderson-Greco guitarbass, built to E#'s specs by Henderson and luthier Carlo Greco, who had once been Guild's chief designer. This guitar covers the waterfront with much less real estate. Greco carved a chunky maple neck with an ebony fretboard. Henderson ascribed to Sharp's request for a streamlined V-shaped body made of limba and a bird's-eye maple top. The three pickups are all Bartolini J Bass, for a sound Sharp describes as "very hi-fi." There's a 5-way switch and a volume control, but no tone controls, since Sharp usually does that with his fingers or pedals. The brass bridge was hand-machined by Henderson and stainless-steel Strat saddles were added.

"Although the scale length is 25.5", the bass strings put out some massive low end and the guitar strings have a sweet snap," says Sharp. "For the first few years of its use, I had a trackpad Velcro'd to the body to interface with a computer for triggering samples in the STEIM software LiSa and later for MAX/MSP use."

Among the other unusual instruments in Sharp's arsenal is his doubleneck Arches H-Line, which, like New Complexity's instruments, opens up the harmonic possibilities of guitar and was inspired by the work of Hans Reichel. But perhaps the most novel is the triple-course bass pantar, which Sharp built in 1990 with the help of woodworker Andrew Zev Weinstein.

Once again, Sharp explains: "The metal body is the top from a 50-gallon sweeping compound can that I found while walking through Chinatown. It was fitted to a wooden structure that would also serve as the base for the three fingerboards, salvaged from musical roadkill. All 12 strings were bass strings and they could be tuned to various open scales or chords. The rim of the metal top served as a natural bridge. I had planned to mount magnetic pickups under the strings, but opted instead for a piezo. It may be played standing with a strap or horizontally using mallets to create a wide range of sounds reminiscent of steel drums, marimba, gamelan instruments, and string bass."

Night Music #203 Elliott Sharp

Elliott Sharp plays his Doubleneck 1—also using it to trigger samples—during an appearance on the television series Night Music, hosted by David Sanborn. Check out Sharp's insane tapping, and the wild sounds it creates, at the 2:00 mark.

Super Chikan's 6-String Tone Fryers

Fans of hard-core modern Mississippi blues know Clarksdale's James "Super Chikan" Johnson for his ferocious tone and entertaining, full-throttle live performances. But over the past decade, he's also earned a reputation among collectors and players for the funky guitars he builds. They're essentially playable folk-art, and what's truly strange is that no matter their origins and mismatched parts, they all bark like junkyard dogs when they're plugged in.

Johnson has made 1-string diddley bows and guitars from gas cans, cigar boxes, and even an old shotgun, but my favorite is the 6-string in the photo here. The body is a bedazzled motor housing from an antique ceiling fan. Johnson calls it his Chikantar, and it has a tone that is rude, loud, quick to break up, and—when he gets past the 12th fret—head-slicing, but without losing its corpulent tonality. Maybe that's because, as Johnson once confided, it weighs in at about 20 pounds. It also takes to fuzz pedals like a bird on a caterpillar.

Photo by Bill Steber

Typically Johnson's instruments, including the gas cans he fashions into guitars that are sometimes painted and decorated to look like chickens—a breed of fowl he claims to talk to and control—are much lighter. And in recent years he's also begun to build or reclaim and redecorate solidbody guitars.

A look at the mismatched pickups on the solidbody above reveals his parts-sourcing strategy: anything goes. Johnson scours pawnshops and junk stores and trash heaps for everything from pickups to, well, ceiling fan motor shells, and whatever is available in his workshop when he's building a guitar goes right into the pot, like a fat hen.

Super Chikan | Mississippi Roads | MPB

Super Chikan and his instruments, including the ceiling-fan-motor-bodied Chikantar, are profiled in this segment of Mississippi Public Television's Mississippi Roads series.

[Updated 9/14/21]

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)