While I have a special place in my heart for the classics, I yearn for reinterpretation that wears its reverence for the past on its sleeve but doesn’t just feel like an imposter. In my own instruments, I try to pay homage to the vintage guitars that inspired me to play, design, and build. That will never change. But it also doesn’t mean I can’t appreciate and even adore new things. This sentiment is true for both guitars and the music they make. Hybrid mashups have existed forever, and a lot of what people think of as original musical examples are in fact reinterpretations of something they just didn’t know previously existed.

One famous example is the saga of Led Zeppelin. I sincerely doubt that when they first “borrowed” musical themes from their heroes they imagined that they’d soon be the biggest act on the world stage. They were just doing what blues and rock musicians had done for ages—played the sounds that they loved, regardless of where they came from. Under the critical microscope of copyright law (magnified by the huge sums of money involved), these reinterpretations were deemed unsavory and even illegal. I don’t think most fans saw it that way. I feel the same way about guitars.

At some point, we all take a stand regarding the derivative nature of new things. Some of us revel in the discovery of an artist or band that seemingly breaks free of any recognizable influence, while others may feel more comfortable with an obvious nod to what has come before. I’ve endured arguments about both camps and have found it curious why it even matters. Certainly, as musicians, we all had to start somewhere.

A lot of what people think of as original musical examples are in fact reinterpretations of something they just didn’t know previously existed.

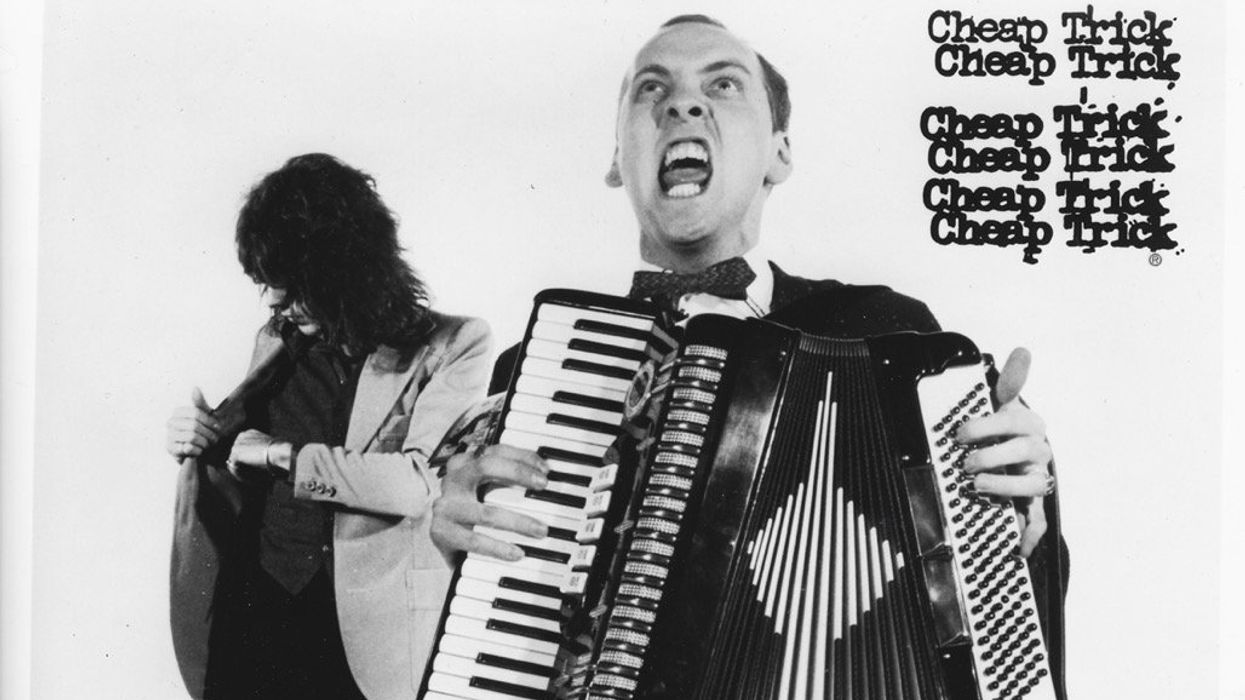

Usually, it begins with a sound that catches your young ear: a song in a TV show, on the internet, or played to you by a friend. Maybe it was your uncle’s record collection. Music is so ubiquitous it can almost disappear into the background like the hum of passing traffic, so it takes something special to get your attention. It might have even been a photograph of a band—one that piques your curiosity as to what they’re all about and what their music sounds like. No matter what draws you in, if the music delivers, you’re hooked. That sound is catalogued in your gray matter and becomes a touchstone for future encounters. It’s up to you to decide if you just want more of the same or the taste of a different flavor.

I think it’s the same with instruments. Perhaps your head exploded when you heard Van Halen for the first time, and that wacky red, white, and black striped guitar made an indelible impression that was forever linked to the sound and feeling that intoxicated you. This permanent scar in your brain fused those two elements until they were the same, and you’ll forever know it’s your benchmark for everything that came after. This is why guitar companies seek artist endorsers—influential musicians who can vouch for the virtue of their products. Like signing a check, popular guitarists put their stink on products, and, in return, the gear puts its sweet smell on them. In turn, we are attracted to the fragrance like bees to a pretty flower.

We’ve all seen guitar collectors whose interests revolve around one model or one manufacturer. Others may run the gamut of “blue chip” legendary instruments—the foundations of electric music from the last half of the 20th century. I’m always surprised when guitarists cut off their willingness to look at newer takes on the instrument—or music for that matter. People can’t help but compare new things to what has come before because that’s how the human brain works. We see something new and the mind searches for a reference to make sense of it. It’s natural.

What comes next is purely up to you. You can deride something for being a copy of a copy, or you can accept that art, in all its forms, stands on the shoulders of what has come before. Sometimes it’s a tribute, sometimes a rip-off, and, occasionally, it’s a tasteful homage to its influences. As time passes, it becomes difficult to create something totally new. I consider all these things before I sit in judgement, but, in the end, it’s the reinterpretation, not the copying, that counts.