“Man, sometimes it takes you a long time to sound like yourself." —Miles Davis

Episode 2 of the Netflix series The Mind, Explained noted that the male zebra finch must come up with his own unique song to impress a mate. Young males listen to the songs of their fathers, and then try to emulate them. Diving deeper into it, scientists hooked the birds up to machines that tracked brain and muscle patterns. They found that, while sleeping, the bird's vocal muscles and brain patterns were very similar to the muscle and brain patterns present when these birds were mimicking their father's songs. But there were reoccurring variations in these patterns suggesting that “these feathered Casanovas appear to be dreaming of variations of their love songs…. Each night the songs get looser and each day they tighten up until a unique, clear melody emerges from the chatter."

This seems like a lot of information to glean from a few dozen electrodes wired into a bird brain, but the fact remains that these birds compose music in their sleep, in order to get laid, and, apparently, it's got to be an original tune, no covers. How eerily human.

Speaking of birds and wasting time in front of a screen, today on TikTok I heard Neil deGrasse Tyson answer the chicken-and-egg question. Tyson explained that the egg came first, but it came out of something that was not technically a chicken. The first chicken was a mutant so different from its parents that it qualified as an entirely different species.

I'm not just randomly stringing together ornithological facts: The point is that everything comes from something, and although some things may start with the same ingredients, each generation gets further away from the original until it's difficult to recognize the source. That's evolution. That's life. That's music.

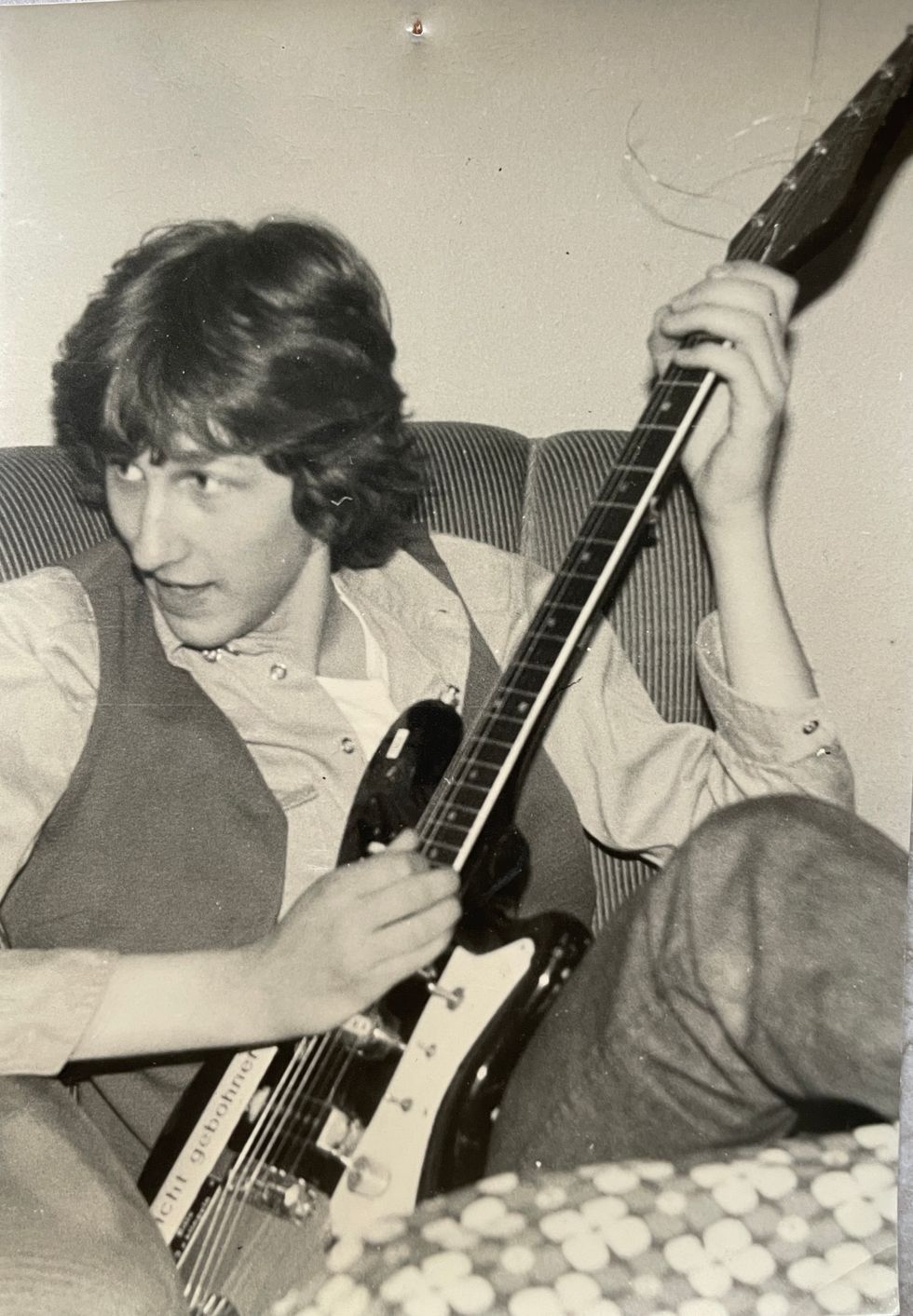

The first time I heard Van Halen, I wasn't even sure I was hearing a guitar. I was in 9th grade and had been playing guitar poorly for a few years, but I was really into music. Before my friend played me that album, I'd never heard anything like Ed, because there had never been anything like Ed. He was this beautiful mutation. I read an early interview and was surprised to learn that Van Halen was influenced by Eric Clapton. I couldn't see the connection. Taking nothing away from Clapton, it's like an eagle giving birth to a dragon. (Maybe that's not the right simile, but I'm sticking with this avian theme and an eagle is the most regal bird I can think of.)

Similarly, although Clapton was influenced by Robert Johnson, Freddie and B.B. King, Chuck Berry, Jimmy Reed, and Muddy Waters, the stuff that made Clapton a god sounded nothing like the guys he was copping. In turn, E.C. influenced anyone who plugged in an electric guitar from 1966 on, including Van Halen, who then took most 1980s guitarists in such a different direction that you can't hear where he came from. Like the first chicken becoming a different species than its mamma, Eric and Ed became different genres than their progenitors.

It's interesting how our personal taste, particularly in music, defines us. You are what you like. Into blues? You're a blues player. Into metal? Etc., etc., etc. To a certain extent, we're a product of our environment, gravitating toward what we're exposed to. But eventually we explore on our own and discover influences outside what we've known, and that leaves its mark.

You never know what's going to connect to you. Por ejemplo: Clapton was my guy when I first got into guitar. When I was 16 and caught him in concert, everything unsuspectingly changed. That night, Albert Lee, who was in Clapton's band, opened the show with his song “Country Boy." Until then, I thought country guitar was corny, like Buck Owens. (No offense. Buck's great. I just didn't get it until later.) Hearing Lee rip up that Tele was the most exciting music I'd ever heard—it totally changed my trajectory. Until then, I was all about blues and rock, but I went a totally different direction. Today, I don't sound anything like Lee or Clapton, but I can trace the genesis of much of what I do back to the music I heard that night.

Like our zebra finch friend, we start by copping the songs of those who got us started and tweak it until it becomes our own.

Music is a never-ending journey of self-discovery. What keeps it interesting is that when you're playing and listening, you're evolving. What we like changes, so no matter where you're going, there is another distant exotic land awaiting.