See how dense, complex, serrated post-hardcore pummels and blooms—thanks to some pawnshop prizes, a scratch-and-dent steal, and a unison bass tuning.

Shiner sprouted from the fertile, black-dirt underground rock scene of the Midwest. Cofounded by guitarist/vocalist Allen Epley in 1992, the band toured with contemporaries Sunny Day Real Estate, Chore, Jawbox, Season to Risk, the Jesus Lizard, and Girls Against Boys, recorded with Shellac’s Steve Albini, and released four albums between 1996 and 2001. Injections of new blood for 1997’s Lula Divina (bassist Paul Malinowski) and 2000’s Starless (Josh Newton on keyboards/guitars and Jason Gerken on drums) helped carve fresh ground and broaden their sound.

Shiner’s sweet spot lives among the smoldering soundscapes that brood, blossom, and bolster their cannonball core. The Egg, from 2001, was a crowning achievement—the early career apex of the band’s evolution from noisy dissonance and powder-keg rock to mosaic, prog-like orchestrations that were equally brutal and beautiful. And after nearly two years of touring behind The Egg, the quartet split up in 2003.

Over the next 15 years, Shiner reunited for special one-off appearances and very short tours. And with the help of the internet and streaming services, their low-key, dormant profile was elevated. Finally, in 2020, Shiner came back to the table with Schadenfreude–a shockingly logical evolution from and continuation of The Egg’s sonic flavor. The album has the lyrical earworms, head-nodding rhythms, gut-punch oomph, and palette-cleansing space travel you’d expect from a band that said goodbye with the jewel “The Simple Truth.”

Ahead of Shiner’s show at Nashville’s DIY arts collective, Drkmttr, PG hopped onstage to dissect the current setups of Epley and Malinowski. Epley details how a lunch-break pawnshop visit landed a remarkable Hohner T for under $100. Malinowski reveals the unique tuning (and demonstrates the monkey-grip it requires to play) that allows his setup to charge like a rhino. And both walk us through their practical-but-powerful pedalboards.

(Unfortunately, renowned gearhead, resident of Pudgemont County, and a regular at the Chug Suckle, Josh Newton, was not on this run as he was tech’ing for Kings of Leon. Spotlights’ Mario Quintero played the role of Newton for this batch of shows, and we featured his setup—along with wife/Spotlights bassist Sarah Quintero’s rig—back in 2021.)

Brought to you by D’Addario Nexxus 360 Rechargeable Tuner.

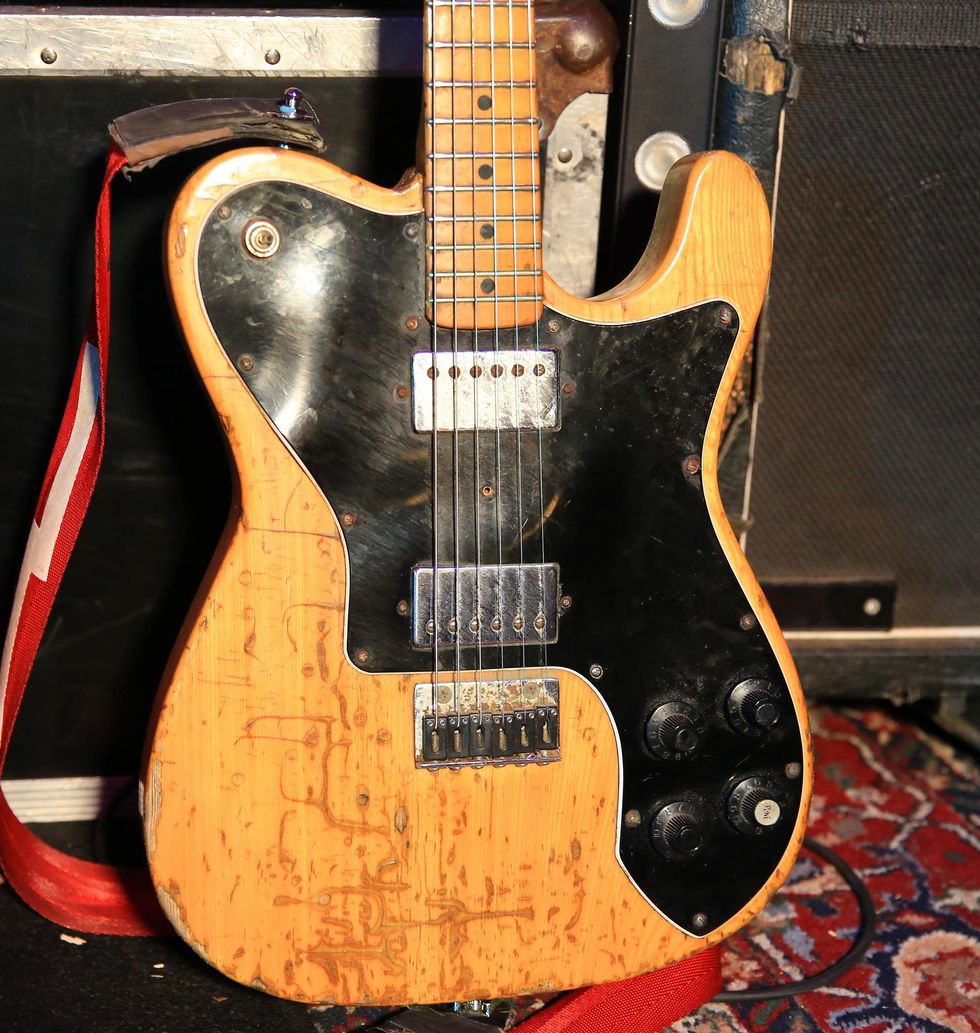

A “Trashy Toy Tele” Becomes the One

If you’ve seen Shiner and Allen Epley, you’ve seen this T-style that’s been to hell and back. Epley’s live staple is a Hohner HG-428N—a Japan-made copy of a Fender Telecaster Deluxe. While Epley has owned the instrument for 30-plus years, he contends that its abuse was dished out prior to scoring this prize at Sol’s Pawn in Kansas City, Kansas. Shiner bassist and extreme bottom feeder Paul Malinowski did the wheeling and dealing and helped Epley land it for under $100. It’s been overhauled several times, to keep it running strong, but Epley feels this one provides a live tone that’s unmatched by anything he owns and adds to Shiner’s sting. He goes with Dunlop Performance+ strings (.011–.050) and is locked into D-standard tuning.

Blacktop Backup

If anything haywire happens to the Hohner, Epley has this Fender Blacktop Jazzmaster HS that was picked from Chris Metcalf, who plays drums in Allen’s other band, the Life and Times. It’s been upgraded with a Staytrem bridge by fellow Shiner bandmate and tech extraordinaire Josh Newton.

Mind the Gap

The solid, stratified sound of Shiner starts with Epley’s stereo setup. The first part of the potent platform is his 1997 Vox AC30 Top Boost reissue that he bought brand new. He loves how it sits in the mix and “fills the gaps in the middle” like double-meat in a club sandwich.

Tommy's Hiwatt?

Surrounding and supplementing the Vox’s mid-focused heft is the above 1971 Hiwatt Custom 100 that chimes in with glassy highs and plenty of low-end heft. He plucked this gem from fellow KC rocker Duane Trower of Season to Risk for $500 cash and a lesser amp. (Epley clearly won that trade.) During the Rundown, he semi-confidently asserts that the head was used for the touring production of the Who’s rock opera Tommy. He uses it with guitar and bass, and it’s been souped-up by turning the normal volume control into a throttle for the pre-gain, giving the amp more grind and growl. The Custom 100 hits a 2x12 cab (procured by Josh Newton) that has a pair of 35-watt speakers.

Allen’s Arsenal

The first two parts of Epley’s pedalboard start on the floor. The TC Helicon Harmony Singer integrates with his guitar—reading whether the chord he’s playing is major or minor—and then accompanies his vocals with a predetermined harmony either above or below his singing key. Next in line on the floor is the Ernie Ball 6166 Mono Volume Pedal. After that is a double dose of dirt compliments of MXR: a Super Badass Distortion and Micro Amp+. Following those is an Electro-Harmonix Micro POG that Epley calls a “kaleidoscope of sound.” A MXR M300 Reverb provides plenty of canyon far and wide, while the Line 6 DL4 spreads Epley’s tone to both amps for stereo delay. A Boss TU-2 Chromatic Tuner keeps his guitars in check and a MXR ISO-Brick M238 powers the pedals.

Paul’s Project P

This P bass started its life as a ’90s MIM Squier model. The only thing stock on the entire instrument is the body. It has a new pickguard, enhanced electronics, a custom-wound pickup from Fountain City Guitarworks (Kansas City), a NOS Kramer Schaller bridge from the ’80s, and a custom neck finished and fine-tuned by KC producer/luthier Justin Mantooth. The secret sauce to Paul Malinowski’s setup and rhino-charging tone has nothing to do with gear, but rather the unison tuning (C-G-C-C) that he employs for most of Shiner’s songs. He hammers away on Dunlop strings (.050–.110) with Dunlop Tortex .73 mm picks (yellow).

A Blast From the Past

Prior to bringing the project P into the mix, Paul would rely on this 1983 Fender Elite Precision Bass II. As with a lot of instruments made in the ’80s, there was some serious innovation on deck. Fender’s high-end attempt at an active bass features noise-cancelling, split-coil passive pickups (Paul mentions the bridge pickup is thin sounding and never stood a chance in Shiner), an active preamp that boosts output and improves control operation, and a Bi-Flex truss rod (allowing adjustments in both directions). This one often rides in D-standard tuning (D-G-C-F). Paul feels this instrument has “a little more throat to it” than the Squier P. And a big reason this Elite looks anything but is because Paul shredded away its finish when he played with flexible copper picks for years.

Pulverizing With Peavey

During Shiner’s initial run, Malinowski pumped his Ps through a Mesa/Boogie 400+ and 2x15 cab. After the band stopped touring, he sold the rig to a friend. On the lookout for a new setup, he found luck with this Peavey Classic 400 that he scooped for $50 from the Musician’s Friend scratch-and-dent warehouse in Kansas City. The fault was resolved with a fresh fuse cap. The 400-watt bruiser runs off 14 tubes (eight 6550s, five 12AX7s, and one 12AT7). Malinowski lives in the crunch channel.

Ranger Rock Ready for Duty

This custom-made Ranger 2x15 was built by fellow Kansas City dweller Scott Reed. The design removed the industrial vibes of the ported Mesa Diesel cab he previously used for an heirloom furniture look. It does have a pair of EV15L drivers in it, too.

Malinowski’s Mass Distortion

The signal from the P goes into the Ernie Ball VP Jr that feeds the Boss TU-2 Chromatic Tuner. The first two tone ticklers are both always on. The Boss GEB-7 Bass Equalizer simply slides out the 500k frequency and the Maxon OD808 Overdrive reissue aggressively agitates the Classic 400. When Pete needs to restrain his buffalo bass tone, he pulls back the volume or changes his playing dynamics. The MXR EVH Phase 90 gets used along with an EBow. The DigiTech Bass Whammy gets used with the EBow and phaser, but is also engaged (in the low-octave setting) when he’s playing riffs on just the unison high strings to thicken everything up. The Boss MT-2 Metal Zone gets center stage for the Starless song “Giant’s Chair” or anytime he wants to ride the feedback bull. The MXR Tremolo has its moment during the intro of “Giant’s Chair” (joining the MT-2 to create a buzzsaw super chop). And the TC Electronic Flashback dazzles and delays in spacy sections.

![Rig Rundown: John 5 [2026]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62681883&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C45%2C0%2C45)

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)