The guitar great who influenced Eddie Van Halen and Yngwie travels with just a Fernandes goldtop once owned by Gary Moore, a versatile Engl, and a prog-rock pedal playground to recreate the Genesis masterpiece Foxtrot.

“I always apologize to the two Erics [Clapton and Johnson], ‘You have no idea how much I’ve ripped from you,’” joked Joe Bonamassa during a recent video with YouTuber Rick Beato. The Grammy-winning bluesman followed that up with a gracious response: “We all get it from somewhere.”

That “somewhere” is a muse that molds every guitarist’s individualistic style and voice. For example, Eddie Van Halen shook the world and confounded guitarists with his explosive two-hand, finger-tapped “Eruption” performance on Van Halen’s 1978 debut. Yngwie Malmsteen put listeners in awe with his dazzlingly clean and swift sweep arpeggios. They both became synonymous with those talented techniques, and were heralded as pioneering groundbreakers. But where did they get the ideas from before expressing and executing them it in their signature style? Both took a page out Steve Hackett’s prog-rock playbook.

Hackett’s two-hand tapping technique can be heard in the early ’70s on Genesis’ albums Nursery Cryme and Foxtrot. Hackett’s sweep picking was first heard on the 1973 Selling England by the Pound track “Dancing with the Moonlit Knight.” Those contributions alone should’ve been enough to land Hackett in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. (His combined work on six Genesis albums in six years earned him a slot in 2010.) On top of that smashing success and influence, he’s recorded nearly 30 solo albums—ranging from prog-rock and blues to world and classical—over a dozen live albums, and even traded licks with Steve Howe in the short-lived supergroup GTR. Hackett might not be recalled like the other guitar greats, but without his shoulders to stand on, those first-name giants might not have shone as bright.

Hackett’s headlining Ryman Auditorium tour stop in late October 2023 celebrated the 50th anniversary of Genesis’ Foxtrot—a seminal, prog-rock tour de force that was recorded when singer Peter Gabriel, bassist/guitarist Mike Rutherford, drummer Phil Collins, keyboardist Tony Banks, and Hackett were in their early 20s. Before the show, PG’s Chris Kies was invited onstage to go over the minimal-but-mighty setup used by Hackett. First tech Vince O’Malley detailed a Fernandes goldtop (once owned by Gary Moore) with its limitless Sustainer circuit and a treasured nylon-string Alvarez built by master luthier Kazuo Yairi in the 1970s. Then Hackett himself joined the fun and plugged his Fernandes into his pedalboard to show off all the sounds, tones, and colors he requires to honor his days in Genesis.Brought to you by D'Addario.

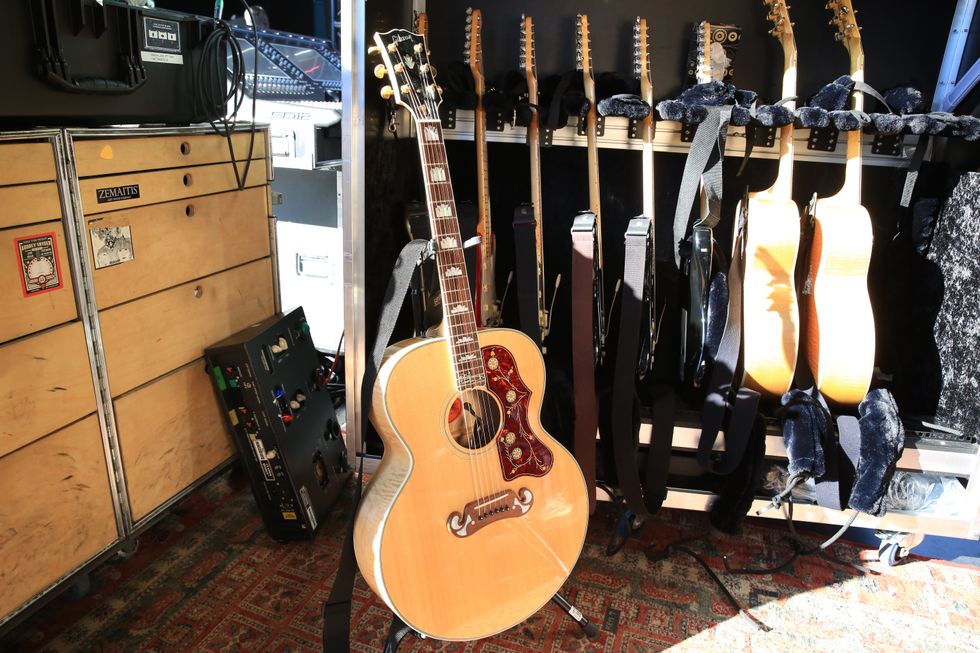

Gary's Goldtop

Goldtops and Steve Hackett have been longtime partners. The most-famous pairing would be Steve and his 1957 Gibson Les Paul that was featured all over Genesis’ recordings during the 1970s. Then in 1981, he befriended another Gibson Les Paul (this one, a 1974) that was diced up for optimal experimentation by adding a Floyd Rose and a Roland Hex pickup to control the the GR-700 Programmable Analog Guitar Synthesizer. As he sought out new tones and capabilities, he encountered a duo of Fernandes instruments—a pink Strat with a Sustainer circuit and a black Burny Les Paul that already had a Floyd and Sustainer.

His main ride is this 1990s Fernandes goldtop decked out with his desired specs—including a Floyd Rose and the Sustainer circuit in the neck—from the culmination of his years of workshopping ideas. It’s affectionately called “Gary,” after guitar hero Gary Moore. Hackett acquired it via Graham Lilley, a shared guitar tech between Moore and himself, and the Moore family estate who helped broker the deal. He has another Fernades goldtop as a backup, but if all goes well, this doesn’t leave Hackett’s hands all night.

Nimble Nylon

For the calmer moments of the Foxtrot replay, Hackett relies on this 1987 Alvarez CY127 CE built by master luthier Kazuo Yairi. It’s constructed with a solid cedar top, fancy rosette, rosewood back and sides, 12-fret mahogany neck with ebony fretboard, 19 frets, rosewood bridge, individual saddles, and factory-installed Alvarez natural response pickup system with pop-up volume, bass, and treble controls. The slotted headstock features rosewood overlay, and gold 3-on-a-plate tuners with pearloid buttons.

Powder Strings

Hackett has always preferred light strings. He suffered a devastating cut to his left forearm that reduced his strength, so lighter strings play a pivotal role in his longevity and ability to play the difficult parts required for Genesis’ music and beyond. He currently uses Ernie Ball Extra Slinkys (.008 –.038) for electric and D’Addario EJ43 Pro-Arté Nylon Light Tension classical strings for the Alvarez. The secret ingredient to Hackett’s speed is the Johnson & Johnson baby powder that tech Vince O’Malley rubs on the guitar necks to reduce any friction Steve may encounter while onstage.

Jackpot!

Much of Hackett’s career has been linked to 50W Marshalls. His longest fling with the British brutes was a 1987 head that ran off a pair of EL34s, but a few years ago Hackett reevaluated his live tone and engaged in an amp shootout. The winner was an Engl Powerball I, a 100W bludgeoner with 6L6s. Tech Vince O’Malley says they only run the amp in the clean channel and preferred it to the rest for its high headroom and pedal-friendly base tone. It still runs into an old Marshall 1960A 300W cab that has a foursome of Celestion G12T-75W speakers.

Steve Hackett's Pedalboard

Hackett has never shied away from effects. It doesn’t matter if it’s analog or digital, true-bypass or not—if it helps capture an idea in his head or articulate an emotion via the fretboard, he’ll try it. To that end, he still employs adventurous pedals in a very pragmatic pedalboard. The main section consists of a couple Line 6 boxes: the DM4 and MM4. He has a pair of Boss PS-6 Harmonists, with one set to double his guitar line and the other for a subtle chorusing effect. Next to those is a MXR EVH Phase 90 that is dimed for a Leslie-ish swoosh. Hackett has been a longtime fan of the DigiTech Whammy, using it from the very first WH-1 model. He currently jacks up his tone with the WH-5. And in the top-right slot rests a TC Electronic Hall of Fame reverb. Down below includes a TC Electronic Flashback 2 X4 Delay, a duet of Tech 21 SansAmp GT2s (for different levels of fury), and an Electro-Harmonix Attack Decay for faux volume swells needed to give his sore Achilles tendon a break after decades of foot-pedal manipulation. Tucked underneath is an Analogman Beano Boost and a DigiTech Mosaic used to mimic 12-string parts on Foxtrot material. Everything is powered by two Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 Plus units.

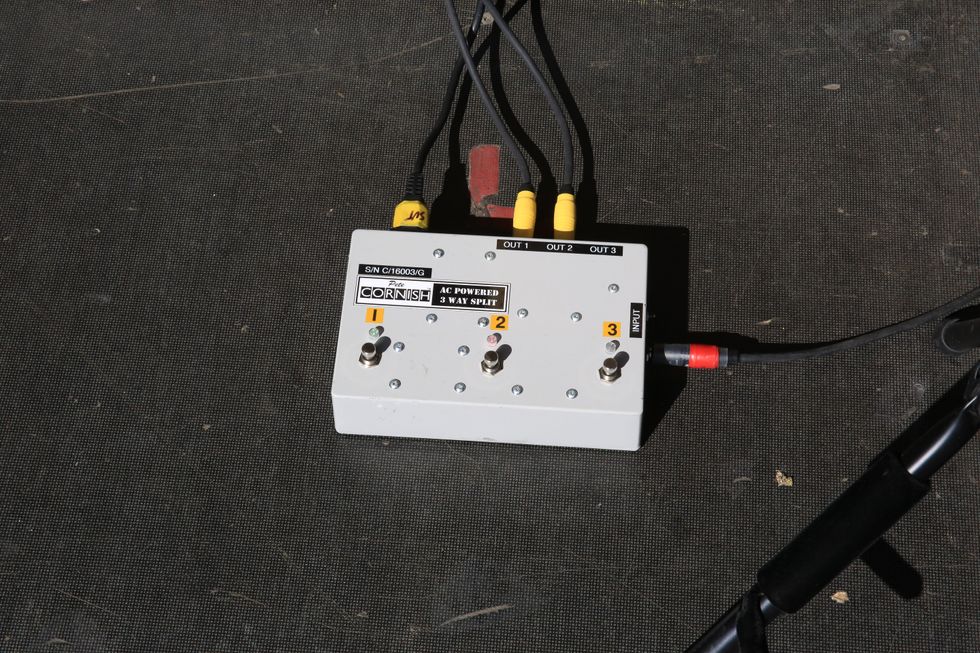

Moving on to the right-side addendum, we have a Dunlop 105Q Cry Baby Bass Wah (Hackett prefers its low-end oomph), an Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamer, and a Cornish Iron Boost treble booster.

To the left, he employs a Fishman Aura Spectrum DI and a Radial ProDI Passive Direct Box for the Alvarez, and a custom switcher box to toggle between electric and acoustic instruments.

Steve Hackett's Rig

Ernie Ball Extra Slinkys

D’Addario Pro-Arte’ Nylon Light Tension EJ43

Engl Powerball

Marshall 1960A 4x12 Cabinet

Celestion G12T-75W Speakers

Tech 21 SansAmp GT2

Boss PS-6 Harmonist

EHX Attack Decay

Fishman Aura

DigiTech Mosaic

Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamer

DigiTech Whammy WH-5

TC Electronic Flashback 2 X4 Delay

MXR EVH Phase 90

Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 Plus

Dunlop 105Q Cry Baby Bass Wah

Radial ProDI Passive Direct Box

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)