Chops: Advanced

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Examine a melody by J.S. Bach and play it in various subdivisions of the beat.

• Apply different rhythms to a short melody.

• Combine various rhythms with unusual subdivisions of the beat.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation.

No matter how hip the notes are that you play, they won’t sound like anything without some sense of rhythm, groove, and flow. The devil is in the details—the distinction between a solid rhythmic feel and a stiff or shaky feel lies in subtle differences of articulation.

In this lesson, we’ll explore some ideas for increasing control of rhythmic details and articulation. It’s helpful to use the same material for all examples, so we will use a strong melody that isn’t very long. In Ex. 1 you can see the first four measures of Bach’s Sarabande from Cello Suite No. 5 (but transposed to A minor). It can be played entirely in 5th position. Memorize it as quickly as possible.

Click here for Ex. 1

This melody is felt in a duple beat (eighth-notes). A good way to test yourself for rhythmic accuracy is to put the same material into a different beat subdivision. For example, try doubling the speed to feel it in 16th-notes (Ex. 2).

Click here for Ex. 2

To feel the notes in a different relationship to the beat, try putting the melody into a triple feel (Ex. 3).

Click here for Ex. 3

Then double up the triplets to play the passage as sextuplets (Ex. 4).

Click here for Ex. 4

For an extra challenge, try playing the melody in quintuplets (Ex. 5) or septuplets (Ex. 6), where the melody turns around on the beat every time it starts. In each case, the last note falls on the downbeat at the end of the third time through the melody. You can use this to check your accuracy, rather than counting, calculating, or reading, which are all detrimental to the groove. Make sure to play the accents. This prevents you from cheating (i.e. just feeling a faster tempo).

Click here for Ex. 5

Click here for Ex. 6

By now, the melody should be pretty well internalized. Let’s forget about the original rhythm in order to make some new rhythms. Reduce the information of the melody to just a series of pitches, with no specific rhythm (Ex. 7). Play through the melody a few times without any concerns about adhering to a set rhythm.

Click here for Ex. 7

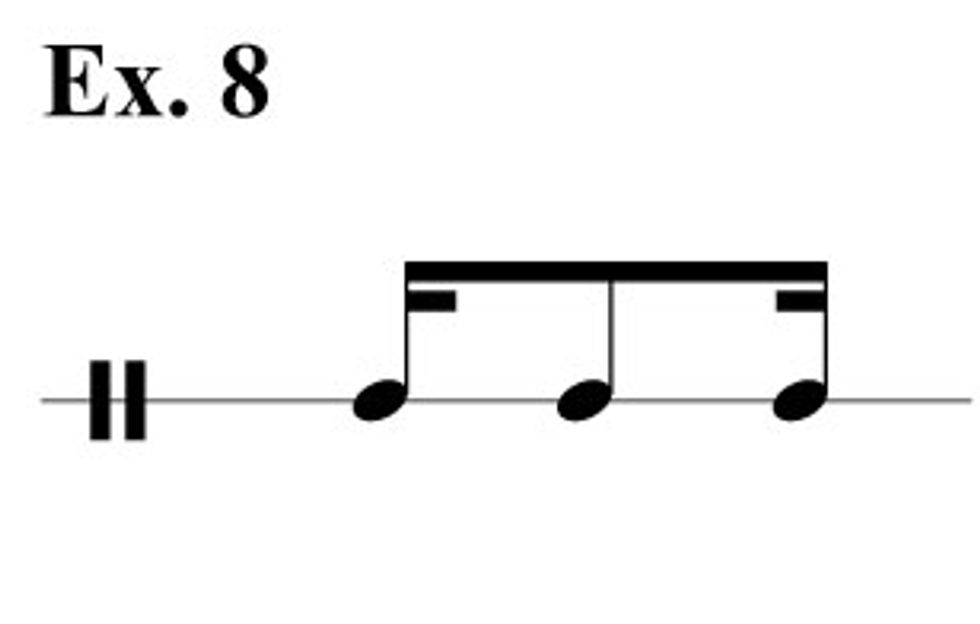

Next, think of a simple rhythmic figure and apply this to the melody. For example, take this typical rhythm in Ex. 8.

Play through the melody using this rhythm (Ex. 9). Notice that in this case, there are 21 notes, so playing them in groups of three in this rhythm produces a repeating seven-beat version of the melody.

Click here for Ex. 9

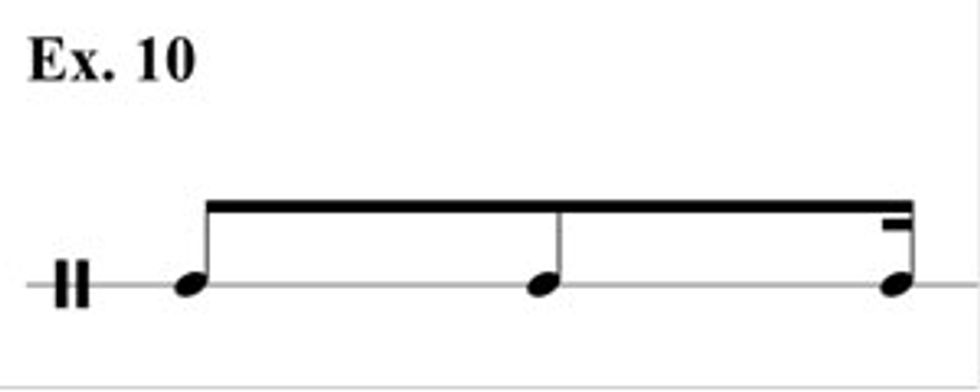

In this 16th-note beat, any rhythm with a length of 4, 8, 12, or 16—or any other multiple of four—will always fall on the beat. Try altering the rhythm slightly so it turns around on the beat. In this case, the rhythm still uses three notes (which are bracketed), but the first note is longer, making a figure that is five 16th-notes long:

Play through Bach’s melody using the new rhythm in a 16th-note feel (Ex. 11) and notice how it turns around on the beat. It takes a while (four repetitions) for the melody to start again on a downbeat. The example shows all four, with accents to show the beginning of each rhythm. Playing these accents helps to feel the shape. Don’t think too much (a surefire route to stiffness). Try to play four times through the melody without reading or calculating, just by letting the rhythmic shape flow in the groove. Make sure to hit the accents to define the shape.

Click here for Ex. 11

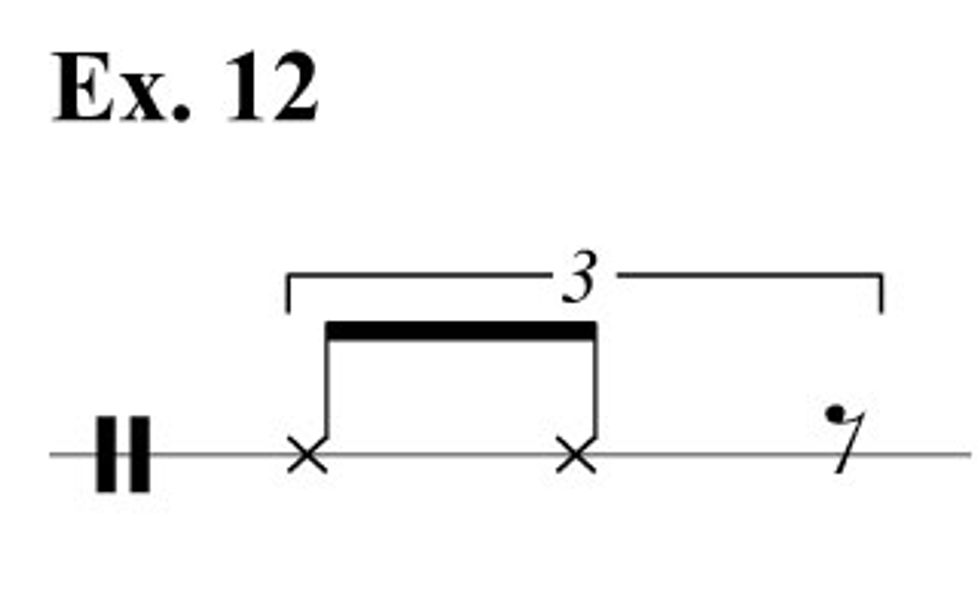

Here’s another twist: Make a simple rhythm, but one that the melody won’t fit into evenly. For example, our 21-note melody fits into groups of three, but not groups of two. Ex. 12 shows a basic rhythm (the “heartbeat”) that uses two notes.

When you play Bach’s melody with this rhythm, it flips inside on the figure itself. The first time through the melody, it starts on the first triplet, but the second time it starts it will be on the second triplet. Try this out, again without thinking about it too much, just trying to play accurately and land back on the downbeat every other time through the melody.

Click here for Ex. 13

Now, you could combine both ideas, for a “wheel within the wheel” effect. Ex. 14 uses the same “heartbeat” rhythmic figure as the previous one, but in a quintuplet feel. Now the melody turns around in relation to the rhythmic figure (as in the previous example), and the figure itself turns around on the beat (as in Ex. 10). The written example shows what this would look like for two times through the melody, plus the first two notes of the third time through. The entire pattern would be five times this length. Remember to play the accents when a note lands on a downbeat.

Click here for Ex. 14

With longer melodies and larger rhythms, this type of exercise can enter extreme levels of difficulty. With shorter melodies, smaller rhythms, and simple beat subdivisions, it can be a simple warm-up.

All of the elements of this exercise are pretty simple, but the things that happen when they are combined can get complex very quickly. Rather than learning and memorizing a lot of material, sometimes it is useful to use very simple material in unexpected ways. It’s one thing to sit and practice and work out some material, but it’s another to be able to do things spontaneously with precision. The idea of this lesson is to gain some fundamental control of rhythmic accuracy without working out “licks.” Use your own material—something even simpler, like a scale fragment, triad, even a single note. Use short, small rhythmic cells. Combine the pitches and rhythms to do something you’ve never done before. Relax and get a groove going, but don’t forget about accents and dynamics. Practice creatively in order to play creatively.