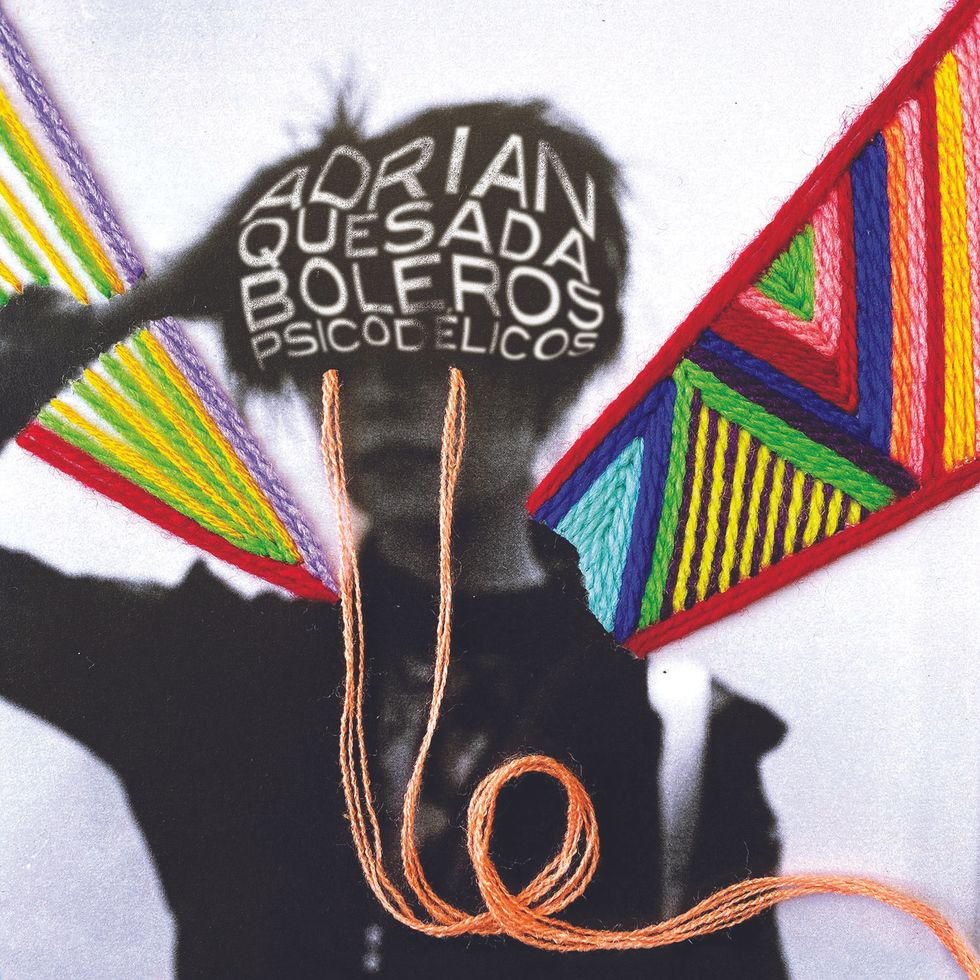

You may know Grammy-winning guitarist and producer Adrian Quesada from his myriad and diverse projects like the nine-piece Latin funk ensemble Grupo Fantasma or Brownout—a gritty Fantasma side project that gained notoriety covering Black Sabbath (as Brown Sabbath) and Public Enemy (Fear of a Brown Planet)—and, more recently, Black Pumas, his critically acclaimed collaboration with vocalist and guitarist Eric Burton. But his most recent outing, Boleros Psicodélicos, an homage to the psychedelicized late-1960s take on the classic Cuban-cum-Mexican genre bolero, is one of his more interesting musical diversions.

The term bolero is loosely translated as “ballad,” although it refers to a specific type of song form derived from traditional folk poetry. As a genre, bolero is a dramatic, semi-theatrical musical style that got something of a facelift in the psychedelic era when groups like Los Angeles Negros and Los Pasteles Verdes reinterpreted them on more modern instruments like electric guitars—drenched in reverb, obviously—and combo organs, although without venturing too far from the music’s more traditional, romantic roots.

Adrian Quesada, iLe - Mentiras Con Cariño (Official Video)

On Boleros Psicodélicos, Quesada uses that classic bolero repertoire as a starting point, but the album is no revivalist tribute or throwback. He wrote most of the tracks, experimented with new timbres and technologies, and his approach is thoroughly modern. He’ll grab vintage gear—and run it through tape, too—if that’s what’s needed to get the sounds he’s after, but he’s not averse to digital effects and plug-ins, and the entire project, ultimately, was recorded inside the box.

“I do have a full analog setup, but I’m no purist with what the process is,” Quesada says. “That was true with this record, in particular, because Boleros Psicodélicos was pretty much recorded remotely. I started everything myself, sent it out to people, and they sent me files back. It was done during the pandemic, so nobody came into the studio.”

The digital process makes collaboration—not to mention editing—infinitely easier, although for Quesada it isn’t always the most productive route for finding the ideal tone.

“I would be dialing knobs for two hours and then I thought, ‘What if I just run it to tape?’ I ran it to tape—that takes 5 minutes—and I’m like, ‘That’s the sound I was hearing.’”

“Plug-ins and whatnot are really pretty amazing now, as is the modeling you can get digitally,” he says, “but man, there were times where I’d spend two hours pulling up all the modeling and plug-ins to get that tape-and-tubes sound. I would be dialing knobs for two hours and then I thought, ‘What if I just run it to tape?’ I ran it to tape—that takes 5 minutes—and I’m like, ‘That’s the sound I was hearing.’”

Boleros Psicodélicos is also dripping in rivers of tremolo. The effect wasn’t that prevalent on the classic psychedelic boleros, but Quesada couldn’t resist. “I love everything with tremolo,” he says. “I put tremolo on everything.” As a general approach, he goes for the best sound, regardless of the technology most aficionados insist is the only way to achieve it. For tremolo—and despite a studio full of classic amps loaded with an assortment of vintage warbles—he often found himself leaning on the completely digital Strymon Flint.

“If I had to keep one pedal on my pedalboard, that would be it,” he says about the device. “I do have a lot of different tremolos in the studio as well—and you can’t beat amp tremolo, a lot of those just sound so musical and a lot more natural—but on the record I used the Strymon Flint a lot. It’s so easy and practical, and has color.”

Adrian Quesada recorded Boleros Psicodélicos during the pandemic, collaborating remotely with Marc Ribot, Ileana Mercedes Cabra Joglar, Gaby Moreno, Money Mark, and many others.

On Boleros Psicodélicos, you can hear Quesada’s tremolo in action in the subtle orchestrated textures he employs on tracks like “Mentiras Con Cariño,” which features Grammy-winning vocalist Ileana Mercedes Cabra Joglar, otherwise known as iLe, as well as the lush—that’s “lush” in a very mid-’70s Holiday Inn-hotel-bar kind of way—“El León.” He uses other tones not usually associated with bolero as well, like a wah for the beautiful and catchy leads on “El Muchacho De Los Ojos Tristes” and an acoustic on “Tus Tormentas.”

Throughout his career, and regardless of genre, he’s always gravitated toward grittier, complex sounds. “With guitar, I’ve always liked a tiny bit of dirt on there,” Quesada says. “Whether it’s pushing an amp to get the sound… tubes crunching up is a very appealing sound to me, although I also like the sound of tape reacting. I like those artifacts that come with it. I don’t like the guitar to be too smooth. I prefer fuzz tones over overdrive. I like things that have a little more color to them. Even if they can be a little bit abrasive, that’s where I gravitate. I like things with character like that.”

“I don’t like the guitar to be too smooth. I prefer fuzz tones over overdrive. I like things that have a little more color to them—even if they can be a little bit abrasive, that’s where I gravitate. I like things with character like that.”

A good example of that on Boleros Psicodélicos—at least, just a touch—is Marc Ribot’s guest performance on “Hielo Seco,” which also features Money Mark of Beastie Boys fame.

“Marc was a big influence on me,” Quesada says. “When I was in college and really discovering this music, he had done a project called Los Cubanos Postizos, which means ‘the Prosthetic Cubans.’ He was doing Cuban music and it was almost traditional—the rhythms were correct—but he was playing electric guitar with a tremolo. You know, my use of the tremolo, honestly, especially in lead playing, a lot of that came from hearing him play. Everything was overdriven with a tremolo. It was just such a different approach to Latin music and his leads were so unique. You could tell he knew jazz, but he wasn’t quite playing like that. It was really outside the box.”

Adrian Quesada’s Gear

Adrian Quesada’s pedalboard currently has eight pedals, but the MVP is his Strymon Flint. “If I had to keep one pedal on my pedalboard, that would be it,” he says.

Guitars

- Fender Parallel Universe Jazz Strat

- Fender Custom Shop Telecaster with humbucker in neck position

- Gibson ES-446

- Gibson ES-125

Amps

- 1965 Fender Deluxe Reverb

- 1972 Fender Deluxe Reverb

- Fender Princeton Handwired Reissue

- Fender Tweed Champ

- Fender Twin

- Gibson GA-20

Effects

- Strymon Flint

- Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail Nano

- Dunlop Cry Baby Wah

- Line 6 ToneCore Echo Park

- Catalinbread Epoch Boost

- Catalinbread Echorec

- EarthQuaker Devices Park Fuzz Sound

- TC Electronic PolyTune 2

Strings & Picks

- D’Addario Super Light Plus (.095–.044) or .010 (.010–.046) sets

- Green Dunlop Tortex .88 mm

Coming full circle, it was a fortuitous glitch in the matrix that led to Ribot appearing on the record. “I hit a wall when I was recording ‘Hielo Seco,’” Quesada continues. “I was going to play guitar on it myself and I was getting tired. I was like, ‘What can I do to finish this song?’ I was working in my yard one day and the YouTube algorithm spit out one of those Marc Ribot Los Cubanos Postizos songs. I thought, ‘He would be perfect for the song,’ and luckily, he did it.”

Often in the studio, Quesada gets those distorted sounds plugging direct into the board and recording to tape, without bothering with an amp. He also prefers the sound of a tape reel that’s been used a few times, which he feels adds character.

“I like what it does after you reuse it a little bit,” he says. “You tame some of the high end and that’s favorable to me for some stuff like drums and guitars. I reuse a reel for just enough—to where I start hearing a little bit too much degradation—and then I get a new one. But I will recycle them for quite a few runs though. It’s like breaking in guitar strings—by the third or fourth show you realize they’re not as stiff anymore.”

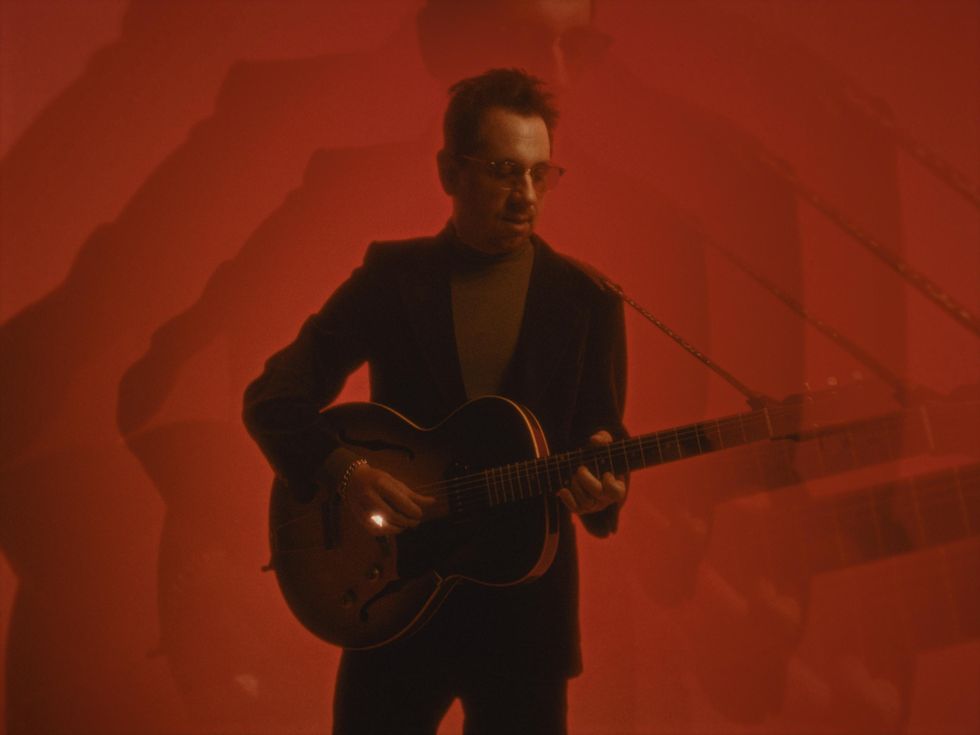

Adrian Quesada fingerpicks a Gibson ES-125 archtop in this outtake from the music video for the lead single, “Mentiras Con Cariño,” from Boleros Psicodélicos.

Photo by César Berrios

One hallmark of Quesada’s approach to production, which stands out on Boleros Psicodélicos, is his exceptional sense of orchestration. He brings in subtle touches, often for just a single verse or repeated figure—like a fingerpicked part or a mild tremolo warble—that, although understated and hard to catch on first listen, transforms an arrangement.

He approaches each composition with a concept in his head and records the basic tracks with those ideas in mind—usually to give the vocalist guideposts to work with—and then revisits the entire arrangement once the vocals are complete.

“I was working in my yard one day and the YouTube algorithm spit out one of those Marc Ribot Los Cubanos Postizos songs. I thought, ‘He would be perfect for the song,’ and luckily, he did it.”

“I hear most of the arrangement already before a singer even does anything,” he says. “But I try not to overdo it. It’s a real fine balance you have to find. I want to put enough color in there for the singer to react to and to feel certain moments that I want accented, but, also, I don’t want to overpower. I want to leave room to hear what they do. It’s like two stages, and when I get the files back, I usually go in there and strip stuff away—I put some stuff back, too—and use their vocals to figure out where I can bring certain things out, but also not step on the vocals. It’s almost like cooking: I try and wait for the end to really add everything.”

That intricate production style—as amazing as it sounds on record—can be something of a disadvantage when trying to perform the music live. What gets left out? What is essential? Does the music suffer? That was a particular challenge for Boleros Psicodélicos, because the music was never intended to be played in front of an audience.

Casada at his Electric Deluxe Studios in South Austin, Texas.

Photo by Jackie Lee Young

“We did some radio promotion, and that was the first time these songs had been played live,” Quesada says. “We had to rehearse and commit to what parts we wanted to keep and what we wanted to scrap. It was a good challenge to get in there and decide what was really crucial. Obviously, there are going to be parts that are not going to be there—because I can’t have a 20-piece band—but honestly, when I’m making an album like that, I try to imagine somewhat what it would be like if we were together in a room. I try to make it seem somewhat natural or human. I don’t like to record 40 guitars just to do it.”

That’s similar to how the Black Pumas’ album was recorded as well. “With Black Pumas, it was almost like night and day. When we made that album, we hadn’t really played live, either. But once we started to play live, all the songs took on another life. It’s almost like completely different arrangements from the album.”

“It’s almost like cooking: I try and wait for the end to really add everything."

Pulling together those influences—which is drawn from years of experience and a well-defined aesthetic sense—is ultimately how Quesada puts the pieces together. It’s how he can take an older, beloved genre like bolero and coax out something that’s contemporary and relevant, and real.

“When I started the Boleros album, I had a playlist of inspiration songs I was using at first to get off the ground, but honestly, I didn’t want to get stuck making a covers album or any sort of carbon copy—you can just go back and hear the originals. I used the older music as a template, but then I ran with it. I tried to make it a little bit more varied and a little truer to myself than just covering it exactly. After a while, I stopped referencing the old stuff and was just off on my own. Obviously, it’s still in the ballpark referencing the older material, but I wasn’t trying to copy anything.”

Adrian Quesada's Boleros Psicodélicos in KUTX Studio 1A

A rare live performance recorded for KUTX in Austin, Texas. Check out Quesada’s unusual all-upstroke picking technique on the first and third songs. The drummer is Jay Mumford, aka J-Zone, an accomplished hip-hop artist. “I remember following him on social media,” Quesada says. “I love that he’s someone who came from a hip-hop production background and then started approaching the drums like that. The dedication he put into being a good drummer was really inspiring. I was watching him and watching him, and then he started posting videos and I was like, ‘This guy is really good.’ During the pandemic, I was looking for somebody to help remote record some drums, so I just hit him up.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)