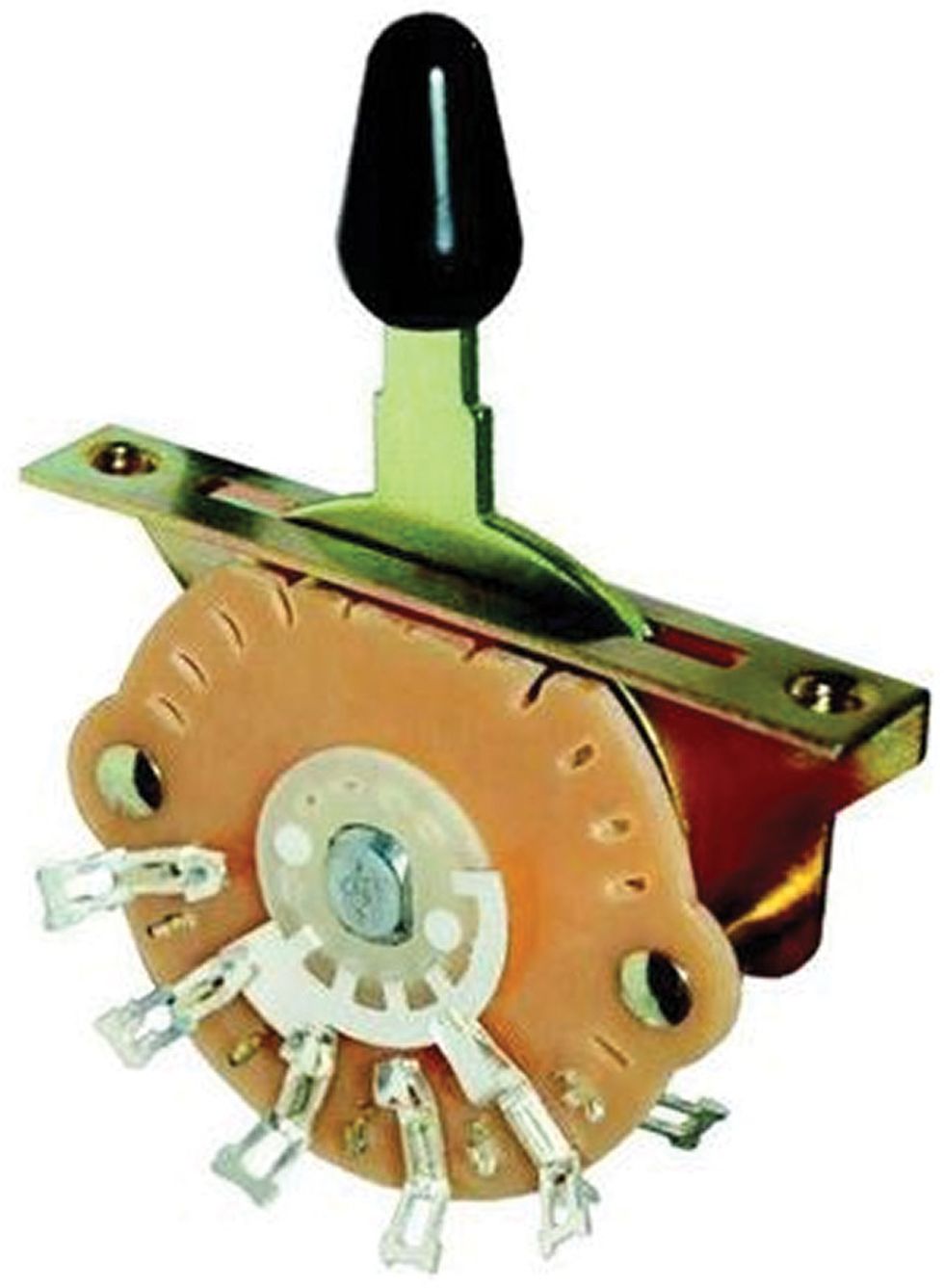

Fig. 1

Here's some exciting news for Strat lovers: If you crave more pickup combinations than are provided by Fender's stock 5-way switch, you need to know about a new blade-style pickup selector from Electroswitch.

Some background: Based in Raleigh, North Carolina, Electroswitch Electronic Products makes a wide variety of items that are important to us guitar nerds. Electroswitch owns the Stackpole, CRL/Centralab, and Oak Grigsby brands, which means all the well-known 3- and 5-way blade pickup selectors, as well as the Telecaster 4-way switch, come from this company. It's clear they have a real passion for switching devices!

Recently Electroswitch introduced a 6-way switch that looks like a standard 5-way pickup selector switch, but instead of the typical four contacts on each of the two switching stages, it offers five, as well as a sixth lever position.

Why is this so cool? It lets you access an additional sound—bridge-plus-neck pickups in parallel. Think Telecaster tone for a Strat and you'll be in the ballpark. This particular dual-pickup combination isn't available on a stock 5-way switch, but it sounds every bit as good as the bridge-plus-middle and neck-plus-middle combos we're used to hearing.

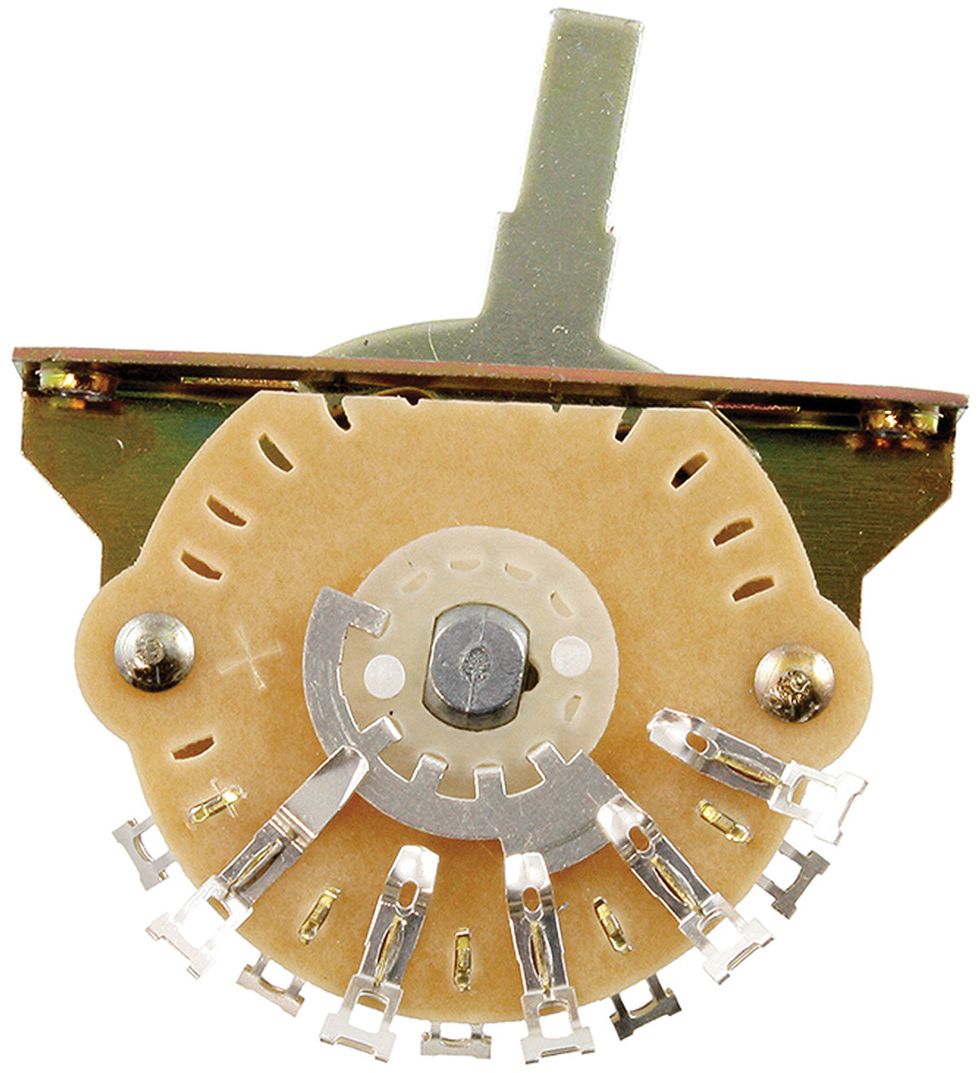

Fig. 2

The extra sixth position isn't limited to bridge-plus-neck in parallel. Alternatively, you could wire it to give you all three pickups in parallel, but that's not a setting most players use, even when it's available as part of the “7-sound mod," which is one of the most requested Stratocaster mods in our shop. (Check out “The 7-Sound Stratocaster" on PG's website for more details on this mod.)

The new 6-way selector (Fig. 1 and 2) resembles a stock 5-way switch, and once installed, it would be virtually indistinguishable from its forebear. It works exactly the same as the 5-way switch through the first five switching positions, but in the sixth position, the contact associated with the bridge pickup remains connected and an additional contact is also engaged. You can attach a jumper between this additional contact and the neck contact to use the bridge and neck pickups together, or two jumpers if you want to engage both the neck and the middle pickups with the bridge pickup.

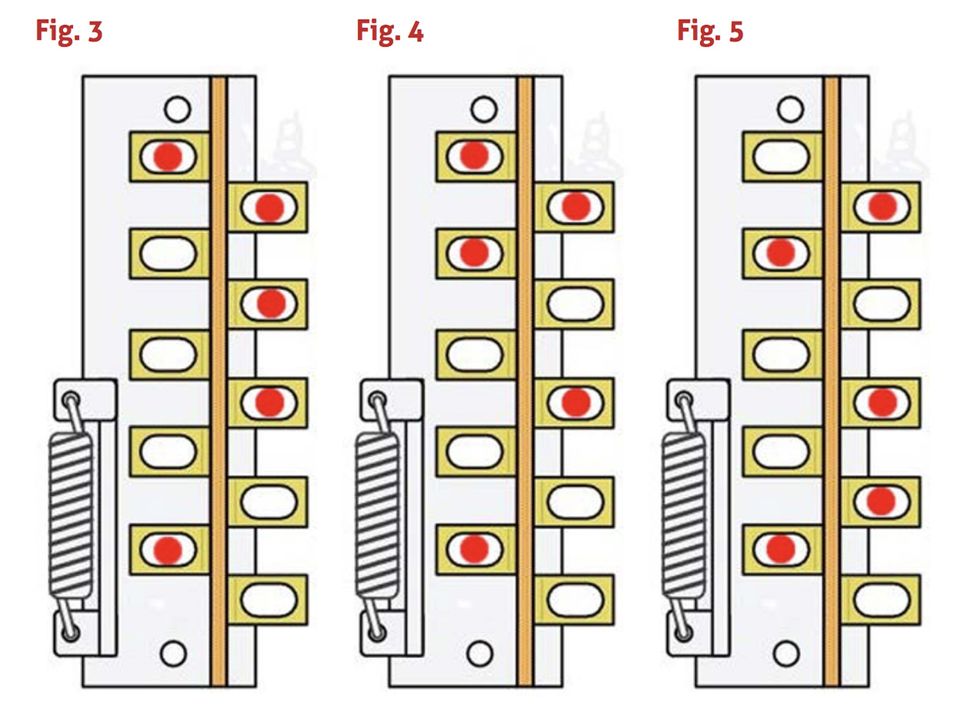

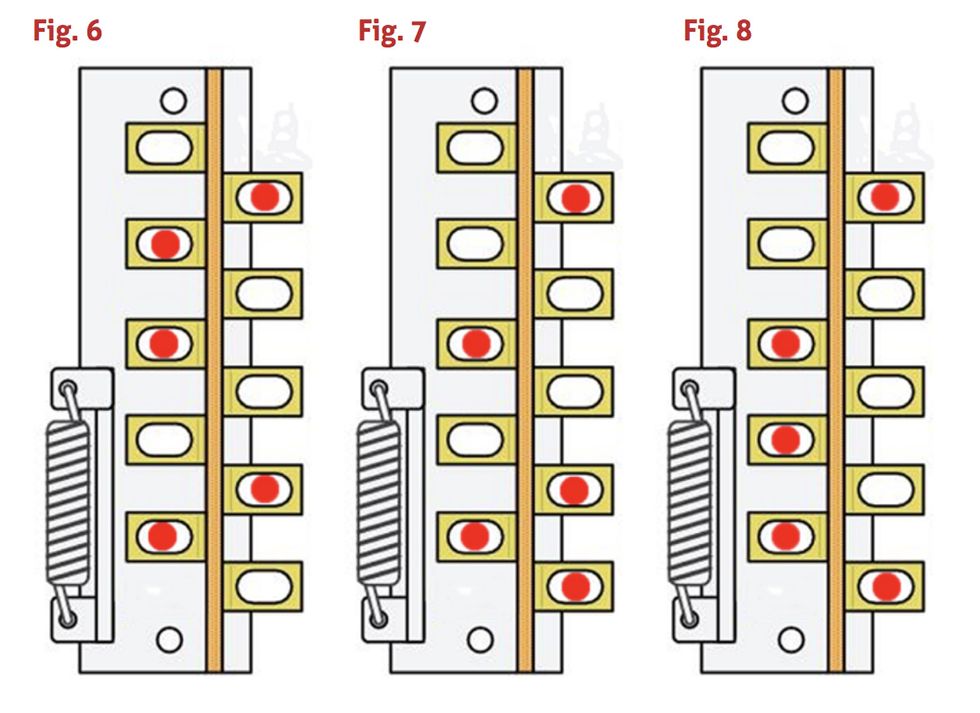

Here's the 6-way selector's switching matrix:

• Position 1: bridge pickup alone (Fig. 3).

• Position 2: bridge + middle pickup in parallel (Fig. 4).

• Position 3: middle pickup alone (Fig. 5).

• Position 4: middle + neck pickup in parallel (Fig. 6).

• Position 5: neck pickup alone (Fig. 7).

• Position 6: additional switching option (Fig. 8).

You mount the 6-way switch the same way you would a traditional 5-way Strat switch, but there's one crucial detail to consider: Electroswitch kept the same 15-degree distance between each of the blade positions as on a 5-way switch—a real bonus because it will feel immediately familiar to experienced Strat players—but this means there's an extra 15 degrees of travel we need to account for. This is divided evenly on either side, so we need to slightly lengthen the slot in the pickguard or control plate to accommodate an extra 7.5 degrees of movement on either end. The typical slot length in a Fender pickguard is about 1 1/32", but this switch needs a slot measuring 1 1/4" for trouble-free operation.

Okay, that's not the end of the world, but because the 6-way switch isn't a 1:1 drop-in replacement, you have to figure out how to lengthen the slot if you're planning to install this new switch in your Strat. This would seem like a small task—and it really is, as long as you have the right tools. You need a very small and sharp rectangular file for this, and you're unlikely to find this kind of file in your local Home Depot. Such files exist, but you'll have to turn to a specialized tool shop to find one.

There are more professional solutions, like using a Dremel tool with a very small router bit. Your local luthier can use small nut-slotting files for this job, or even better, his bridge-pin-hole slotting files. The trick is to find a file that matches the width of the slot and cuts on the bottom and sides at the same time.

I've seen countless pickguards ruined when someone tried to lengthen the slot without the proper tools. If you don't take the time to get this right, you'll end up spoiling your pickguard. Lengthening the blade's slot sounds easy, but it poses a real challenge—especially with vintage or expensive custom pickguards you don't want to butcher. And doing this on a metal Telecaster control plate is a task best left to a professional.

And that's it. In a future column, I'll share some wiring ideas for your Strat that incorporate this new 6-way switch. But next time, we'll return to regular guitar mods and explore even more series switching for your favorite Telecasters. Until then, keep on modding!