When I visited Southern California for the first time a few years ago, I was struck by several observations. First, 70-degree weather in January was a nice departure from the Northeastern Pennsylvania winter. There was a steady, warm breeze cascading through Anaheim almost constantly. Second, property there is ridiculously expensive, and any thoughts we had about moving to SoCal were quickly squashed—even though my wife still talks about it! And third, since I was attending NAMM and writing about guitars, I thought about how Southern California used to be one of the guitar-building meccas.

Think about it: The Golden State had Fender, Rickenbacker, Bartell, Standel, and even Paul Bigsby pioneering and leading the new wave of electric guitars in the ’50s and ’60s. If you drove north a bit to Bakersfield, you’d find Hallmark guitars and Semie Moseley making his iconic Mosrites, too. But nestled in between Bakersfield and Los Angeles was a smaller shop in San Fernando that built guitars for only about two years. Yes, starting a guitar company from scratch among these other legends proved to be a tough task, but little Murphy Music Industries gave it the old college try.

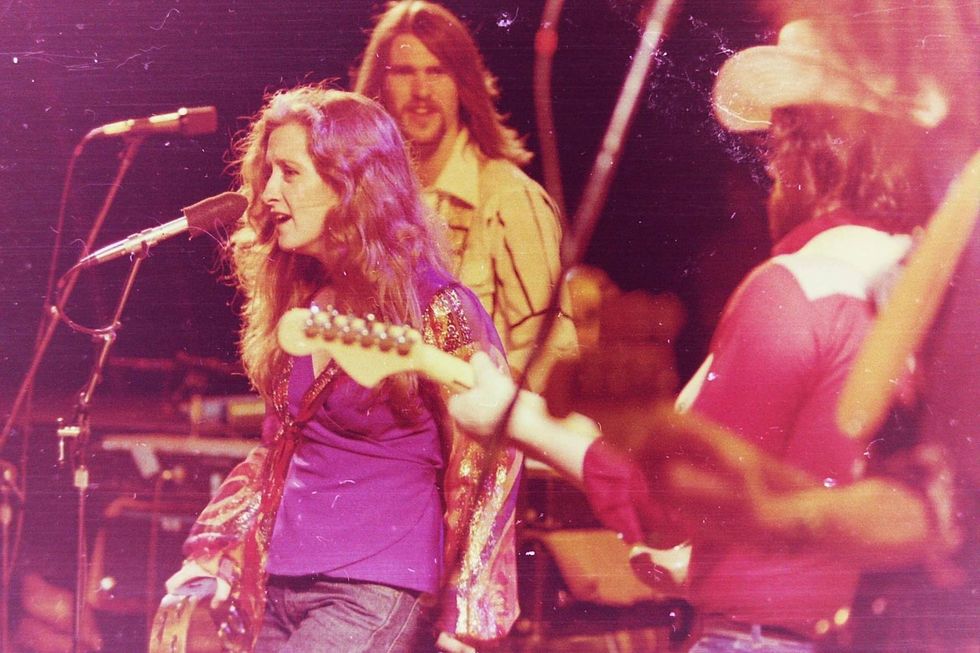

Murphy Music Industries sprang from the mind of Patrick Murphy, who wanted to promote his children’s musical ambitions, as they were all rather talented and formed a group that become popular on local TV. What better way to promote the family name than with its own guitar lineup? Murphy guitars began production in late 1965 with a few cool models that included a 12-string, a semi-hollow, and an ultra-cool heart-shaped guitar called the Satellite. But perhaps their most commonly seen 6-string was the Squire II-T (Photo 1), which was the second version of their Squire, with two pickups.

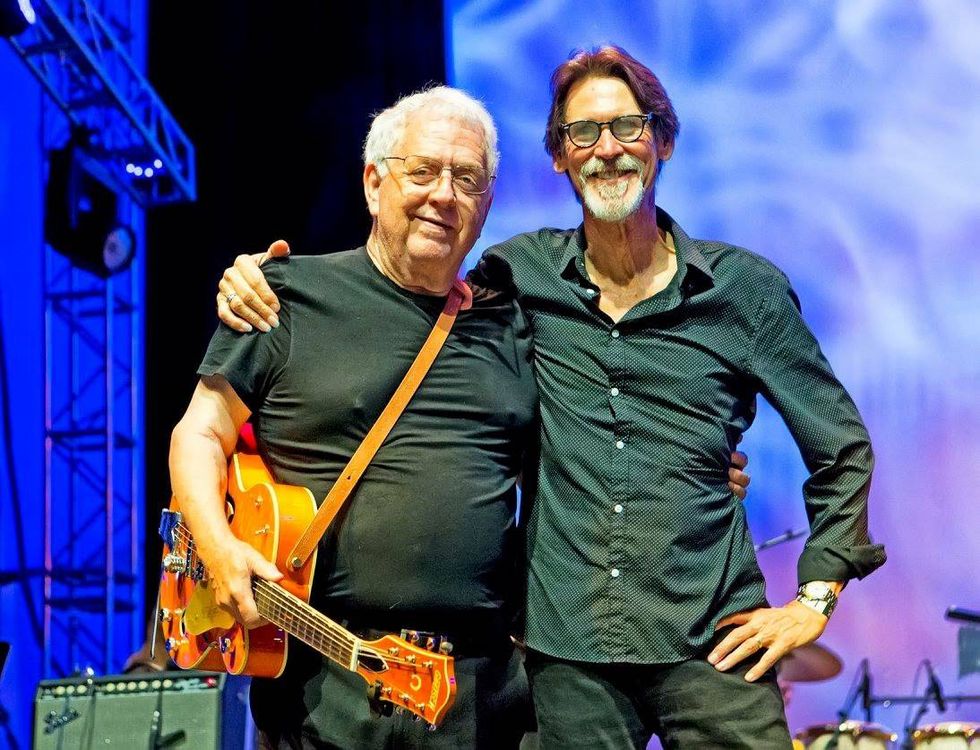

The Murph Squire II-T featured a poplar body and a full-scale maple neck. The tremolo on my 1966 has a very industrial feel—complete with squeaks and clangs—that was often the case with Germany-made guitars of the era. Lo and behold, I discovered the tremolo units were indeed sourced from Germany. However, just about every other part of the Murph Squire was either made in-house (like the pickups) or sourced from the U.S. (Kluson tuners, Carling switches, Daka-ware knobs). Most of the Squires I’ve seen came in this red-burst finish, although there were other custom colors floating around out there. Personally, I love the headstock shape (Photo 2) and the plastic overlay with “Murph” screen-printed across the top.

Photo 2

Sonically, these Squires are total surf machines and the pickups provide an impressive high-end zing. They aren’t aggressive pickups, necessarily, but with a good reverb, you just want to play spaghetti-western themes all day long. The necks on Murph guitars are often described as thin, but I like the contour and find them super comfy. The body has a nice offset design that balances well, and the poplar construction probably lends to the bright sound. All said, the guitar overall is a bit crude compared to contemporary offerings. In fact, I am often struck by the engineering of early electric guitars, because they were all a bit crude in one way or another. Even the bigger boys down the highway had their warts. Still, if I had a Murph in my early days, I probably would’ve made that move to the California beaches.

The company had some interesting ideas and short-lived business flirtations with Sears and Mattel, but in the end, Murphy’s company experienced the all-too-common brief and grueling life of many small businesses. I still give Mr. Murphy a lot of credit. He started a guitar company for his children during the rock ’n’ roll craze of the early 1960s, the same era when cheaper imported guitars were really pouring into the U.S. market. Not only was he competing with Japanese imports and a bounty of American electrics, he was also competing locally with some of the most iconic names in the music business. By 1967, his company filed for bankruptcy and Murphy went on to run a food truck until his retirement. Luckily for us, we are left with his remaining Murph guitars to lather in reverb!

See and hear this 1966 Murph Squire II-T demoed by Mike Dugan. And wait for the Blue Cheer!

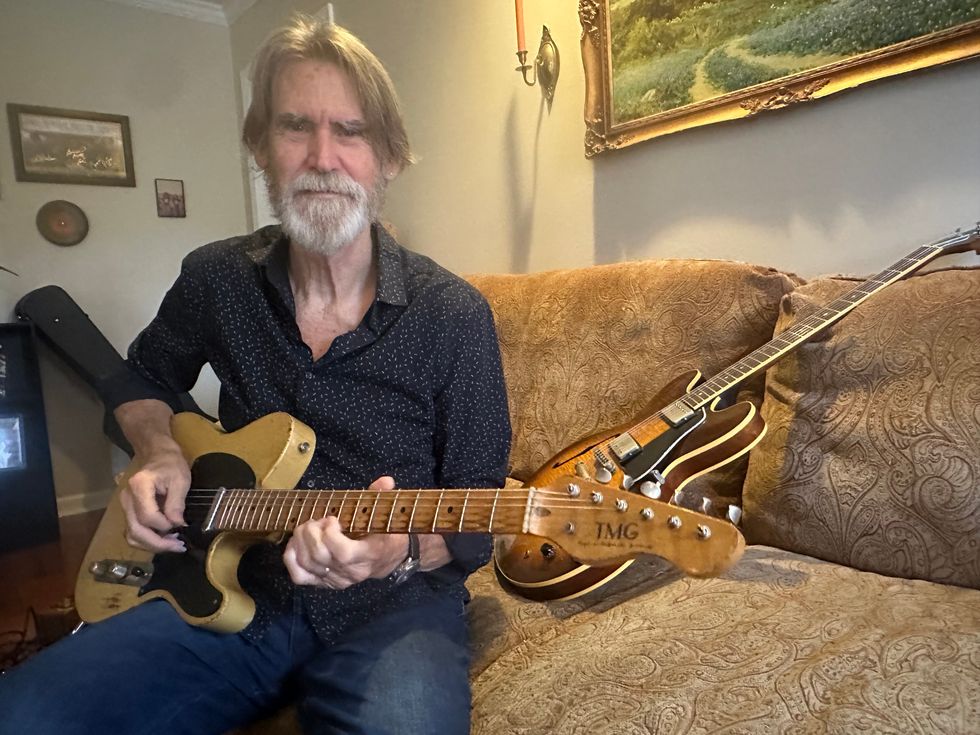

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski

Will McFarlane keeps a Deluxe Memory Man in line with a Princeton—his rig for noodling on the couch at home.Ted Drozdowski